Librarians, 18'76-19'76

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIBRARY DESIGN SHOWCASE P

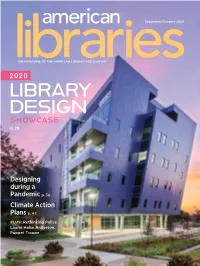

September/October 2020 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION 2020 LIBRARY DESIGN SHOWCASE p. 28 Designing during a Pandemic p. 36 Climate Action Plans p. 42 PLUS: Rethinking Police, Laurie Halse Anderson, Puppet Troupe PLA 2020 VIRTUAL STREAM NOW ON-DEMAND Educational programs from the PLA 2020 Virtual Conference are now available on-demand*, including: Bringing Technology and Arts Programming to Senior Adults Creating a Diverse, Patron-Driven Collection Decreasing Barriers to Library Use Going Fearlessly Fine-Free Intentional Inclusion: Disrupting Middle Class Bias in Library Programming Leading from the Middle Part Playground, Part Laboratory: Building New Ideas at Your Library Programming for All Abilities Training Staff to Serve Patrons Experiencing Homelessness in the Suburbs We're All Tech Librarians Now Cost: for PLA members for Nonmembers for Groups *Programs are sold separately. www.ala.org/pla/education/onlinelearning/pla2020/ondemand September/October 2020 American Libraries | Volume 51 #9/10 | ISSN 0002-9769 2020 LIBRARY DESIGN SHOWCASE The year’s most impressive new and renovated spaces | p. 28 BY Phil Morehart 22 FEATURES 22 2020 ALA Award Winners Honoring excellence and 42 leadership in the profession 36 Virus-Responsive Design In the age of COVID-19, architects merge future-facing innovations with present-day needs BY Lara Ewen 50 42 Ready for Action As cities undertake climate action plans, libraries emerge as partners BY Mark Lawton 46 Rethinking Police Presence Libraries consider divesting from law enforcement BY Cass Balzer 50 Encoding Space Shaping learning environments that unlock human potential BY Brian Mathews and Leigh Ann Soistmann ON THE COVER: Library Learning Center at Texas Southern University in Houston. -

Award Honorary Doctorate Degrees Funding

10 Board Meeting January 31, 2019 AWARD HONORARY DEGREES, URBANA Action: Award Honorary Doctorate Degrees Funding: No New Funding Required The Senate of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign has recommended that honorary degrees be conferred on the following people at Commencement Exercises on May 11, 2019: Michael T. Aiken, former Chancellor of the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign -- the honorary degree of Doctor of Science and Letters Chancellor Aiken was the sixth chancellor of the University of Illinois at Urbana- Champaign, leading the campus from 1993 until his retirement in 2001. Only one chancellor has served longer. Dr. Aiken was devoted to the excellence of the Urbana campus and undertook many initiatives with a lasting impact still felt today. During Campaign Illinois, he worked to establish more than 100 new endowed faculty positions. He enhanced the undergraduate experience by increasing opportunities for students to study abroad, expanding the number of living/learning communities in the various student residence halls, developed discovery classes for first-year students, and instituted New Student Convocation. Chancellor Aiken worked toward the creation of Research Park on the south campus to provide a vibrant environment for the campus efforts in economic development and innovation. Dr. Aiken was key to establishing the Campustown 2000 Task Force to improve both the physical appearance of Campustown and its safety and livability. Dr. Aiken made a priority of building strong relationships between the university and the greater Champaign-Urbana community. During his tenure, and through his leadership, gateways were built at the boundaries of the campus to serve as doors and windows between the campus and the community. -

Ruth Horie: an Oral History Biography and Feminist Analysis by Valerie

Ruth Horie: An Oral History Biography and Feminist Analysis By Valerie Brett Shaindlin THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Library and Information Science (MLISc) at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa 2018 Thesis Committee: Dr. Noriko Asato Dr. Vanessa Irvin Dr. Andrew Wertheimer (Chair) Ruth Horie: An Oral History Biography and Feminist Analysis 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...……..…….....5 A Note on Language…………………………...…………………………..….……………..…....6 Abstract……………………………………………………………………...…………….……....8 PART I: Oral History………………………….…………………....……………..….….….….....9 Family History…………….…....…………………………….....……………….……......9 Youth (1950-1968)……….……………....……………………....….……..……….……26 Childhood……………....………………………….…………...…..…………….26 School Years………..…………………………………..…..…………................35 Undergraduate Education (1968-1979)………….……..…………………………..........43 The Hawaiian Renaissance…………………………………………….………...45 Kahaluʻu Flood (1964) and Family Relocation (1974)……………..…...…...…..48 Employment………………………………………………………….……..……51 Graduate Education and Early Career (1979-1991)...........................................................54 Master’s Degree in Library Studies (1979-1981)……….…………………….....54 Employment at the East-West Center (1981-1986)…....……...…...………….....56 Employment at Bishop Museum (1986-1990).....……..……................……........60 University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa (1991-2012)...................................................................65 Employment at Hamilton -

Downloading—Marquee and the More You Teach Copyright, the More Students Will Punishment Typically Does Not Have a Deterrent Effect

June 2020 THE MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAN LIBRARY ASSOCIATION COPING in the Time of COVID-19 p. 20 Sanitizing Collections p. 10 Rainbow Round Table at 50 p. 26 PLUS: Stacey Abrams, Future Library Trends, 3D-Printing PPE Thank you for keeping us connected even when we’re apart. Libraries have always been places where communities connect. During the COVID19 pandemic, we’re seeing library workers excel in supporting this mission, even as we stay physically apart to keep the people in our communities healthy and safe. Libraries are 3D-printing masks and face shields. They’re hosting virtual storytimes, cultural events, and exhibitions. They’re doing more virtual reference than ever before and inding new ways to deliver additional e-resources. And through this di icult time, library workers are staying positive while holding the line as vital providers of factual sources for health information and news. OCLC is proud to support libraries in these e orts. Together, we’re inding new ways to serve our communities. For more information and resources about providing remote access to your collections, optimizing OCLC services, and how to connect and collaborate with other libraries during this crisis, visit: oc.lc/covid19-info June 2020 American Libraries | Volume 51 #6 | ISSN 0002-9769 COVER STORY 20 Coping in the Time of COVID-19 Librarians and health professionals discuss experiences and best practices 42 26 The Rainbow’s Arc ALA’s Rainbow Round Table celebrates 50 years of pride BY Anne Ford 32 What the Future Holds Library thinkers on the 38 most -

College and Research Libraries

ROBERT B. DOWNS The Role of the Academic Librarian, 1876-1976 . ,- ..0., IT IS DIFFICULT for university librarians they were members of the teaching fac in 1976, with their multi-million volume ulty. The ordinary practice was to list collections, staffs in the hundreds, bud librarians with registrars, museum cu gets in millions of dollars, and monu rators, and other miscellaneous officers. mental buildings, to conceive of the Combination appointments were com minuscule beginnings of academic li mon, e.g., the librarian of the Univer braries a centur-y ago. Only two univer sity of California was a professor of sity libraries in the nation, Harvard and English; at Princeton the librarian was Yale, held collections in ·excess of professor of Greek, and the assistant li 100,000 volumes, and no state university brarian was tutor in Greek; at Iowa possessed as many as 30,000 volumes. State University the librarian doubled As Edward Holley discovered in the as professor of Latin; and at the Uni preparation of the first article in the versity of · Minnesota the librarian present centennial series, professional li served also as president. brarHms to maintain, service, and devel Further examination of university op these extremely limited holdings catalogs for the last quarter of the nine were in similarly short supply.1 General teenth century, where no teaching duties ly, the library staff was a one-man opera were assigned to the librarian, indicates tion-often not even on a full-time ba that there was a feeling, at least in some sis. Faculty members assigned to super institutions, that head librarians ought vise the library were also expected to to be grouped with the faculty. -

LHRT Newsletter LHRT Newsletter

LHRT Newsletter NOVEMBER 2010 VOLUME 10, ISSUE 1 BERNADETTE A. LEAR, EDITOR BAL19 @ PSU.EDU Greetings from the Chair BAL19 @ PSU.EDU and librarians. The week As we finalize details we will following Library History inform the membership as to Seminar XII, Wayne how they may participate. Wiegand threw down a challenge. He offered to It is time to turn to finding a contribute $100 to the venue for Library History Edward G. Holley Lecture Seminar XIII (2015). The endowment, and urged all request for proposals is previous LHRT Chairs and included in this newsletter. I Board members to do the invite LHRT members to same. In less than thirty- consider whether your six hours $2,400 was institution might be a good pledged. Ed’s son Jens was site. We are a community of one contributor (both to people with a love for the the fund and to this issue). histories of libraries, reading, His heartfelt message of print culture, and the people, thanks for honoring his places and institutions that are father in this way made me part of those histories. Why proud to be a member of not make a little bit of history LHRT. yourself by hosting this wonderful conference? The LHRT Program Committee is hard at work In the meantime, I will “see” to bring quality sessions to you virtually in January our annual meeting. We meeting in cyberspace, and see will have the Invited many of you in person at Speakers Panel, the ALA’s annual meeting in New Research Forum Panel, and Orleans in June. -

Cooperative and Centralized Cataloging and Processing: a Bibliography, 1850-1967

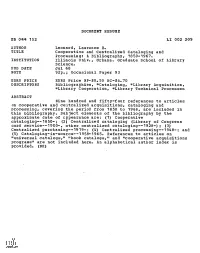

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 044 152 LI 002 209 AUTHOR Leonard, Lawrence E. TITLE Cooperative and Centralized Cataloging and Processing: A Bibliography, 1850-1967. INSTITUTION Illinois Univ., Urbana. Graduate School of Library Science. PUB DATE Jul 68 NOTE 92p.; Occasional Paper 93 EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.50 HC-$4.70 DESCRIPTORS Bibliographies, *Cataloging, *Library Acquisition, *Library Cooperation, *Library Technical Processes ABSTRACT Nine hundred and fifty-four references to articles on cooperative and ceatralized acquisitions, cataloging and processing, covering the period from 1850 to 1968, are included in this bibliography. Subject elements of the bibliography by the approximate date of appearance are:(1) Cooperative cataloging--1850-;(2) Centralized cataloging (Library of Congress card service--1900-, other centralized cataloging - - 1928 -); (3) Centralized purchasing--1919-; (4) Centralized processing--1948-; and (5) Cataloging-in-source--1958-1965. References to articles on "universal catalogs," "book catalogs," and "cooperative acquisitions programs" are not included here. An alphabetical author index is provided. (NH) slr 5- 4/7 University of Illinois Graduate School of Library Science OCCASIONAL PAPPI U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH.EDUCATION a WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THEPERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT. POINTSOF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DONOT NECES- SARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE0 P EDU- CATIONPOSITIONOR POLICY. COOPERATIVE AND CENTRALIZED CATALOGING AND PROCESSING:A -

The Newberry Annual Report 2016 – 17

The Newberry A nnua l Repor t 2016 – 17 Letter from the Chair and the President hat a big and exciting year the Newberry had in 2016-17! As Wan institution, we have been very much on the move, and on behalf of the Board of Trustees and Staff we are delighted to offer you this summary of the destinations we reached last year and our plans for moving forward in 2017-18. Financially, the Newberry enjoyed much success in the past year. Excellent performance by the institution’s investments, up 13.2 percent overall, put us well ahead of the performance of such bellwether endowments as those of Harvard and Yale. Our drawdown on investments for operating expenses was a modest 3.8 percent, well Chair of the Board of Trustees Victoria J. Herget and below the traditional target of 5.0 percent. In fact, of total operating Newberry President David Spadafora expenses only 22.9 percent had to be funded through spending from the endowment—a reduction by more than half of our level of reliance on endowment a decade ago. Partly this change has resulted from improvement in Annual Fund giving: in 2016-17 we achieved the greatest-ever single- year tally of new gifts for unrestricted operating expenses, $1.75 million, some 42 percent higher than just before the economic crisis 10 years ago. Funding for restricted purposes also grew last year, with generous gifts from foundations and individuals for specific programs and projects. Partly, too, our good financial results are owing to continued judicious control of expenses, exemplified by the fact that total staffing levels were 2.7 percent lower in 2016-17 than in 2006-07. -

In Resistance to a Capitalist Past: Emerging Practices of Critical Librarianship Lua Gregory and Shana Higgins

In Resistance to a Capitalist Past: Emerging Practices of Critical Librarianship Lua Gregory and Shana Higgins Introduction In previous work, we’ve explored capitalism and neoliberal ideology in relation to oppression and inequalities, how consciousness raising as defned by Paulo Freire and Ira Shor can lead to informed action, and how the intersections of critical pedagogy and core values such as social responsibility, diversity, and the public good, can contextualize social justice work within the practice of librarianship.1 In this chapter, we revisit capitalism, by examining its inextricable historical connections to the proliferation of libraries and the growth of librarianship as a profession in the United States in the late nineteenth century. We fnd that the rise of capitalism and the “efciency movement” during the Progressive Era (1890–1920) led to a replicating of libraries in the image and model of corporations, and the creation of an educational system that favored practicality and connections to the market, within which we locate historical tensions between theory and practice. Tis chapter is neither historiography nor discourse analysis, but perhaps borrows from both. Our goal is to illuminate the economic and ideological contexts from which the library profession in the United States fourished, and has continued to be implicated. Despite the close alignment of American li- brarianship with a hegemonic economic ideology, there have been critical and 1 Lua Gregory and Shana Higgins, Information Literacy and Social Justice (Sacramento, CA: Library Juice Press, 2013). Te Politics of Teory and the Practice of Critical Librarianship resistant voices within the profession throughout the past century. -

History of Urban Main Library Service

History of Urban Main Library Service JACOB S. EPSTEIN THEMOST IMPORTANT early date for urban public libraries would certainly be 1854, the year the Boston Public Library opened its doors. But as Jesse Shera has noted: “The opening, on March 20,1854, of the reading room of the Boston Public Library. ..was not a signal that a new agency had suddenly been born into American urban life. Behind the act were more than two centuries of experimentation, uncertainty, and change.”l Before the advent of public libraries there were numerous social li- braries, mercantile libraries and other efforts to have a community store of books which could be borrowed or consulted. A common prin- ciple evident in each of them was the belief that the printed word was important and should be made available to the ordinary citizen who could not own all the literature which was of value. Although it was a subscription library, rather than a public library as we think of it today, Benjamin Franklin’s Library Company of Phila- delphia, organized in 1731, was the first library in America to circulate books and the first to pay a librarian for his services. In his Autobiogra- phy, Franklin declared, “These libraries have improved the general conversation of the Americans, made the common tradesmen and farm- ers as intelligent as most gentlemen from other countries, and perhaps have contributed in some degree to the stand so generally made throughout the colonies in defense of their privileges.”2 Here is that recurrent theme of self-improvement that runs throughout the Ameri- can public library movement. -

Disciplining Sexual Deviance at the Library of Congress Melissa A

FOR SEXUAL PERVERSION See PARAPHILIAS: Disciplining Sexual Deviance at the Library of Congress Melissa A. Adler A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Library and Information Studies) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2012 Date of final oral examination: 5/8/2012 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Christine Pawley, Professor, Library and Information Studies Greg Downey, Professor, Library and Information Studies Louise Robbins, Professor, Library and Information Studies A. Finn Enke, Associate Professor, History, Gender and Women’s Studies Helen Kinsella, Assistant Professor, Political Science i Table of Contents Acknowledgements...............................................................................................................iii List of Figures........................................................................................................................vii Crash Course on Cataloging Subjects......................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Setting the Terms: Methodology and Sources.......................................................5 Purpose of the Dissertation..........................................................................................6 Subject access: LC Subject Headings and LC Classification....................................13 Social theories............................................................................................................16 -

Illuminating the Past

Published by PhotoBook Press 2836 Lyndale Ave. S. Minneapolis, MN 55408 Designed at the School of Information and Library Science University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 216 Lenoir Drive CB#3360, 100 Manning Hall Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3360 The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill is committed to equality of educational opportunity. The University does not discriminate in o fering access to its educational programs and activities on the basis of age, gender, race, color, national origin, religion, creed, disability, veteran’s status or sexual orientation. The Dean of Students (01 Steele Building, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-5100 or 919.966.4042) has been designated to handle inquiries regarding the University’s non-discrimination policies. © 2007 Illuminating the Past A history of the first 75 years of the University of North Carolina’s School of Information and Library Science Illuminating the past, imagining the future! Dear Friends, Welcome to this beautiful memory book for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Information and Library Science (SILS). As part of our commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the founding of the School, the words and photographs in these pages will give you engaging views of the rich history we share. These are memories that do indeed illuminate our past and chal- lenge us to imagine a vital and innovative future. In the 1930’s when SILS began, the United States had fallen from being the land of opportunity to a country focused on eco- nomic survival. The income of the average American family had fallen by 40%, unemployment was at 25% and it was a perilous time for public education, with most communities struggling to afford teachers and textbooks for their children.