Who Invented Catapults and Trebuchets?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weapon Group Feats for Pathfinder: Class: Weapon Group Proficiencies

Weapon Group Feats for Pathfinder: Class: Weapon Group Proficiencies at 1st Level: Alchemist Basic weapons, Natural, Crossbows, any other 1 Barbarian Basic weapons, Natural, any other 4 Bard Basic weapons, Natural, any other 3 Cavalier Basic weapons, Natural, Spears, any other 3 Cleric Basic weapons, Natural, deity’s weapon group, any other 2(3 groups if not following a deity) Druid Basic weapons, Natural, druid weapons, any other 1 Fighter Basic weapons, Natural, any other 5 Gunslinger Basic weapons, Natural, firearms, any other 3 Monk Basic weapons, and all monk weapons Inquisitor Basic weapons, Natural, deity’s weapon group, Bows or Crossbows, any other 3 (4 groups if not following a deity) Magus Basic weapons, Natural, any other 4 Oracle Basic weapons, Natural, any other 1 (+3 if taking Skill at Arms) Paladin/AntiPaladin Basic weapons, Natural, any other 4 Ranger Basic weapons, Natural, any other 4 Rogue Basic weapons, Natural, any other 3 Sorcerer Basic weapons, Natural, spears, crossbows , any other 1 Summoner Basic weapons, Natural, spears, crossbows , any other 1 Witch Basic weapons, Natural, spears, crossbows , any other 1 Wizard Basic weapons, Natural, spears, crossbows This system doesn’t change Racial Weapon Familiarity. Weapon Group Name: Weapons In Group: Axes bardiche, battleaxe, dwarven waraxe, greataxe, handaxe, heavy pick, hooked axe, knuckle axe, light pick, mattock, orc double axe, pata, and throwing axe Basic club, dagger, quarterstaff, and sling Blades, Heavy bastard sword, chakram, double chicken saber, double -

A Reconstruction of the Greek–Roman Repeating Catapult

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivio della ricerca - Università degli studi di Napoli Federico II Mechanism and Machine Theory 45 (2010) 36–45 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Mechanism and Machine Theory journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mechmt A reconstruction of the Greek–Roman repeating catapult Cesare Rossi *, Flavio Russo Department of Mechanical Engineering for Energetics (DIME), University of Naples ‘‘Federico II”, Via Claudio, 21, 80125 Naples, Italy article info abstract Article history: An ‘‘automatic” repeating weapon used by the Roman army is presented. Firstly a short Received 21 February 2009 description is shown of the working principle of the torsion motor that powered the Received in revised form 17 July 2009 Greek–Roman catapults. This is followed by the description of the reconstructions of these Accepted 29 July 2009 ancient weapons made by those scientists who studied repeating catapults. The authors Available online 4 September 2009 then propose their own reconstruction. The latter differs from the previous ones because it proposes a different working cycle that is almost automatic and much safer for the oper- Keywords: ators. The authors based their reconstruction of the weapon starting from the work of pre- History of Engineering vious scientists and on their own translation of the original text (in ancient Greek) by Ancient automatic weapons Mechanism reconstruction Philon of Byzantium. Ó 2009 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction Among the designers of automata and automatic devices in ancient times Heron of Alexandria (10 B.C.–70 A.D.) was probably the best known. -

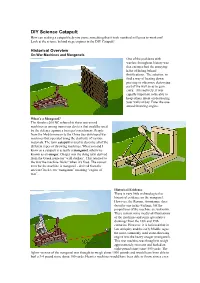

DIY Science Catapult

DIY Science Catapult How can making a catapult help you prove something that it took mankind millennia to work out? Look at the science behind siege engines in the DIY Catapult! Historical Overview On War Machines and Mangonels One of the problems with warfare throughout history was that enemies had the annoying habit of hiding behind fortifications. The solution: to find a way of beating down, piercing or otherwise destroying part of the wall so as to gain entry. Alternatively, it was equally important to be able to keep others intent on destroying your walls at bay. Enter the one- armed throwing engine. What’s a Mangonel? The Greeks c200 BC referred to these one-armed machines as among numerous devices that could be used by the defence against a besieger’s machinery. People from the Mediterranean to the China Sea developed war machines that operated using the elasticity of various materials. The term catapult is used to describe all of the different types of throwing machines. What you and I know as a catapult is actually a mangonel, otherwise known as an onager. Onager was the slang term derived from the Greek name for ‘wild donkey’. This referred to the way the machine ‘kicks’ when it’s fired. The correct term for the machine is mangonel - derived from the ancient Greek term “manganon” meaning “engine of war”. Historical Evidence There is very little archaeological or historical evidence on the mangonel. However, the Roman, Ammianus, does describe one in his writings, but the proportions of the machine are unknown. There remain some medieval illustrations of the machines and some speculative drawings from the 18th and 19th centuries. -

Catapults and Trebuchets (Catapulting, Trebuchets and Physics, Oh My!)

Catapults and Trebuchets (Catapulting, Trebuchets and Physics, Oh My!) GRADE LEVELS: This workshop is for 9th through 12th grade CONCEPTS: A lever is a rigid object that can multiply the force of an another object Levers are made of different parts such as the fulcrum, effort arm, and load Levers are made of three classes Data from experiments can be translated into graphs for further study Experiments must be constantly modified for optimum results OBJECTIVES: Create catapult from various components Identify kinetic and potential energy Identify various parts of levers Use deductions made from trial runs and adjust catapult for better results Identify different classes of levers. Collect data from catapult launches and graph results ACADEMIC CONTENT STANDARDS: Science: Physical Sciences 9.21, 9.22, 9.24, 9.25, 12.5 VOCABULARY/KEY WORDS: Lever: a simple machine used to move a load using a board/arm, and fulcrum Fulcrum: the point on which a lever rotates Board/Arm: the part of the lever that force is applied to and that supports the load Force: the effort used to move the board/arm and the load Load: the mass to be moved Counterweight: a weight that balances another weight Kinetic energy: energy of motion as an object moves from one position to another Potential energy: stored energy due to an object’s position or state of matter Trebuchet: a form catapult that utilized a counterweight and sling to throw a load Catapult: a large lever used as a military machine to throw objects COSI | 333 W. Broad St. | Columbus, OH 43215 | 614.228.COSI | www.cosi.org EXTENSIONS AT COSI: Big Science Park: Giant Lever Progress: Identify various levers used in the 1898 portion of the exhibition. -

Hungarian Archaeology E-Journal • 2018 Spring

HUNGARIAN ARCHAEOLOGY E-JOURNAL • 2018 SPRING www.hungarianarchaeology.hu PLUMBATA, THE ROMAN-STYLE DARTS. A Late Antique Weapon from Annamatia TAMÁS KESZI1 It is possible to view an unusual object in the display showing Roman military equipment at the permanent exhibit of the Intecisa Museum, a special weapon of the army in Late Antiquity, the plumbata.2 The meaning of the Latin word is ‘leaden’, but if the construction and use of the implement is taken into account it could be called a dart in English. With this ca. 50 cm long, hand-thrown weapon the heavy infantry could have begun to disrupt the diployment of the enemy from a distance. WRITTEN SOURCES The name and description of the projectile weapon called a plumbata in Latin is known from numerous sources from Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. (VERMAAT 2015) (Fig. 1) Fig. 1: Depiction of a plumbata tribolata and mamillata. The lead weight is missing from the latter (Source: http:// rekostwargames.blogspot.hu/2016/11/roman-unit-menapii-seniores.html, date of download: 19 April 2018) According to Flavius Vegetius Renatus, who lived in the Late Imperial period, the expert soldiers of two legions in Illyricum used the plumbata, and so they were called Mattiobarbuli (I 17. II 15. 16. 23. III 14. IV 21. 44.). The emperors Diocletian (284–305) and Maximian (286–305) honored the two units with the title Jovian and Herculean for their prowess. From Vegetius’s description it seems that the two units used the plumbata prior to Diocletian coming to power, but it is perhaps only after this, in the last decades of the 3rd century, that its use spread to the other units of the empire as well. -

Inventor Center the Catapult Forces Challenge EDUCATOR’S GUIDE

Hands-On in the Inventor Center The Catapult Forces Challenge EDUCATOR’S GUIDE Complex Spring Catapult, Leonardo daVinci from Leonardo’s Catapults , http://members.iinet.net.au/~rmine/Leonardo.html WHATWHAT’’’’SSSS INSIDE? • Essential Questions • Glossary • Making thethethe Most ofofof Your Visit • Resources • CorrelationCorrelationssss tototo Standards • Activities (Coming Soon) • Facilitation ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS During your facilitated hands-on experience in the Inventor Center: Catapult Forces Challenge , the facilitator will be posing essential questions to your students in two categories: The In- ventive Process and the Science of Catapults and Trebuchets. These questions may also be use- ful for you as a teacher to gain background information as well as for facilitating higher order thinking during class discussions. The Inventive Process Inventor Center encourages students to explore the thrilling process of invention. The Inventor Center includes a series of participatory stations: build, experiment, learn and share. Students will define the problem, build a prototype, experiment with the prototype, learn how well the prototype works (solves the problem), and share their ideas or inventions with others. Who is an inventor? An inventor is someone who uses technology in a new way to solve a problem. An invention is a unique or novel device, method, or process. Inventions are different than discoveries because a discovery is detecting something that already ex- ists. In the Inventor Center everyone is an inventor. What is the inventive process? There are many ways to invent. Most inventive processes consist of four main parts: learning, building, testing (or exper- imenting), and sharing. These four parts of the inventive process can happen in any order. -

Catapult to the Front of the Line

Name: Date: Catapult to the Front of the Line GOAL Create a catapult that will hurl a penny through a target from the furthest distance away. MATERIALS TIME TO CREATE r!,rP!vlDu4! Acr,turY Read the following, hightighting important information, and answer the questions. lmagine that you are in the midst of a snowball fight. ln addition to preparing for battle, you also need to think about protection. Hiding behind something is helpfu[, but what if your enemy is able to break down your barrier? Throughout history, finding a way to destroy the enemy's protection while maintaining a safe distance was cha[[enging-untilthe invention of the catapult, the one-armed throwing machine. Ancient Greeks referred to the catapult as a mangone[, meaning "engine of war." The mangonel, weighing approximately z tons, functioned by ftinging heavy objects over and through walls. Because of its powerful kicking motion, mangonels were also referred to as onagers, a name derived from onagros, meaning "wild donkey." A ballista was another type of catapult. lt was designed similarty to the crossbow. Ballistas relied on the work of torsion to release ammunition that looked like giant arrows. Over time, gravity catapults, such as the trebuchet, were invented. Trebuchets were designed to hur[ a heavy object into a high arc, which was quite useful for breaking down castle walls, especially if the ammunition involved fire. Catapults have been one of the most effective weapons for warfare. A sling is attached to the end of the catapult's arm. ln lowering the arm, the user stores energy in the ropes, and when the arm is released, the arm is flung forward. -

The Book of the Crossbow Free

FREE THE BOOK OF THE CROSSBOW PDF Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey | 400 pages | 26 Mar 2009 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486287201 | English | New York, United States Crossbow by Dayle Campbell Gaetz Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about The Book of the Crossbow problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Crossbow by Dayle Campbell Gaetz. Fourteen-year-old Matt has only one goal in life: to become a hermit. He has no use for school, but he loves the solitude of the forest. When he hikes up to the cabin he built for The Book of the Crossbow, he discovers a mysterious stranger named Forrest has moved in. At first Matt doesn't connect Forrest's appearance with the rash of local robberies. Forrest seems to be the perfect hermit Fourteen-year-old Matt has only one goal in life: to become a hermit. Forrest seems to be the perfect hermit, and he teaches Matt the skills he needs to achieve his goal, including how to hunt with a crossbow. But when Forrest tries to kill an endangered Roosevelt elk, Matt questions the ethics of his new friend. When Matt discovers a stolen rifle in his cabin, he finds himself trapped in a dangerous situation. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. More Details Original Title. Other Editions 5. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. -

The Xanten-Wardt and Carlisle Catapult Finds

The Xanten-Wardt Roman torsion catapult and catapult parts from Carlisle Alan Wilkins The Xanten-Wardt frame from a Roman torsion bolt-shooting catapult of the 1st century AD was discovered in 1999 in a gravel quarry in north west Germany at 51˚ 40ˈ N, 6˚ 27ˈ E. The site was once an arm of the Rhine, but is now the Südsee, a water-sport lake NNE of the Xanten Archaeological Park. The sumptuous official report on the find has now been published by Verlag Philipp von Zabern as Xanten Berichte Band 18: Die Frühkaiserzeitliche Manuballista Aus Xanten-Wardt. This exciting discovery has added far more to our understanding of these machines than previous finds of catapult frame parts from Ampurias, Caminreal and elsewhere. Not only has the metal plating survived, but for the first time the wood of the frame and the front end of the slider and stock have been preserved. The iron and bronze plating includes the battle shields for the spring-cord, organic material from which has been identified by electron microscope as sinew rope. The four bronze washers and washer-bars are there, with one complete washer pin and two broken ones. Fig. 1 The Xanten-Wardt frame after conservation (Maarten Dolmans) Most of the Xanten-Wardt report is rightly devoted to the details of the long and painstaking recovery of the machine from its coffin of solidified sand, grit and pebbles. X- rays and CT scans were used to locate the buried parts, in order to guide the delicate task of removing the concretion. -

Military Technology in the 12Th Century

Zurich Model United Nations MILITARY TECHNOLOGY IN THE 12TH CENTURY The following list is a compilation of various sources and is meant as a refer- ence guide. It does not need to be read entirely before the conference. The breakdown of centralized states after the fall of the Roman empire led a number of groups in Europe turning to large-scale pillaging as their primary source of income. Most notably the Vikings and Mongols. As these groups were usually small and needed to move fast, building fortifications was the most efficient way to provide refuge and protection. Leading to virtually all large cities having city walls. The fortifications evolved over the course of the middle ages and with it, the battle techniques and technology used to defend or siege heavy forts and castles. Designers of castles focused a lot on defending entrances and protecting gates with drawbridges, portcullises and barbicans as these were the usual week spots. A detailed ref- erence guide of various technologies and strategies is compiled on the following pages. Dur- ing the third crusade and before the invention of gunpowder the advantages and the balance of power and logistics usually favoured the defender. Another major advancement and change since the Roman empire was the invention of the stirrup around 600 A.D. (although wide use is only mentioned around 900 A.D.). The stirrup enabled armoured knights to ride war horses, creating a nearly unstoppable heavy cavalry for peasant draftees and lightly armoured foot soldiers. With the increased usage of heavy cav- alry, pike infantry became essential to the medieval army. -

Catapult Challenge Home Learners Pack

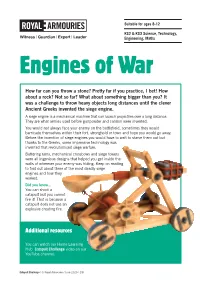

Suitable for ages 8-12 KS2 & KS3 Science, Technology, Engineering, Maths Engines of War How far can you throw a stone? Pretty far if you practice, I bet! How about a rock? Not so far? What about something bigger than you? It was a challenge to throw heavy objects long distances until the clever Ancient Greeks invented the siege engine. A siege engine is a mechanical machine that can launch projectiles over a long distance. They are what armies used before gunpowder and cannon were invented. You would not always face your enemy on the battlefield, sometimes they would barricade themselves within their fort, stronghold or town and hope you would go away. Before the invention of siege engines you would have to wait to starve them out but thanks to the Greeks, some impressive technology was invented that revolutionised siege warfare. Battering rams, mechanical crossbows and siege towers were all ingenious designs that helped you get inside the walls of wherever your enemy was hiding. Keep on reading to find out about three of the most deadly siege engines and how they worked. Did you know... You can shoot a catapult but you cannot fire it! That is because a catapult does not use an explosive creating fire. Additional resources You can watch our Home Learning Hub Catapult Challenge video on our YouTube channel. Catapult Challenge / © Royal Armouries / June 2020 / 1/8 History of the catapult The first catapults We do not exactly know when the first catapult was made but we do know that the Ancient Greeks used them. -

Military Engineering 5-6 Syllabus

Fairfax Collegiate 703 481-3080 · www.FairfaxCollegiate.com Military Engineering 5-6 Syllabus Course Goals 1 Physics Concepts and Applications Students learn the basics of physics, including Newton’s laws and projectile motion. They will apply this knowledge through the construction of miniature catapult structures and subsequent analysis of their functions. 2 History of Engineering Design Students learn about the progression of military and ballistics technology starting in the ancient era up until the end of the Middle Ages. Students will identify the context that these engineering breakthroughs arose from, and recognize the evolution of this technology as part of the engineering design process. 3 Design, Fabrication, and Testing Students work in small teams to build and test their projects, including identifying issues and troubleshooting as they arise. Students will demonstrate their understanding of this process through the design, prototyping, testing, and execution of an original catapult design. Course Topics 1 Ancient Era Siege Weapons 1.1 Brief History of Siege Warfare 1.2 Basic Physics 2 The Birth of Siege Warfare 2.1 Ancient Greece 2.2 Projectile Motion 3 Viking Siege! 3.1 History of the Vikings 3.2 Building with Triangles 4 Alexander the Great and Torsion Catapults Fairfax Collegiate · Have Fun and Learn! · For Rising Grades 3 to 12 4.1 The Conquests of Alexander the Great 4.2 The Torsion Spring and Lithobolos 5 The Romans 6 Julius Caesar 7 The Crusades 8 The Middle Ages 9 Castle Siege Course Schedule Day 1 Introduction and Ice Breaker Students learn about the course, their instructor, and each other.