A Catapult of About 1404”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIY Science Catapult

DIY Science Catapult How can making a catapult help you prove something that it took mankind millennia to work out? Look at the science behind siege engines in the DIY Catapult! Historical Overview On War Machines and Mangonels One of the problems with warfare throughout history was that enemies had the annoying habit of hiding behind fortifications. The solution: to find a way of beating down, piercing or otherwise destroying part of the wall so as to gain entry. Alternatively, it was equally important to be able to keep others intent on destroying your walls at bay. Enter the one- armed throwing engine. What’s a Mangonel? The Greeks c200 BC referred to these one-armed machines as among numerous devices that could be used by the defence against a besieger’s machinery. People from the Mediterranean to the China Sea developed war machines that operated using the elasticity of various materials. The term catapult is used to describe all of the different types of throwing machines. What you and I know as a catapult is actually a mangonel, otherwise known as an onager. Onager was the slang term derived from the Greek name for ‘wild donkey’. This referred to the way the machine ‘kicks’ when it’s fired. The correct term for the machine is mangonel - derived from the ancient Greek term “manganon” meaning “engine of war”. Historical Evidence There is very little archaeological or historical evidence on the mangonel. However, the Roman, Ammianus, does describe one in his writings, but the proportions of the machine are unknown. There remain some medieval illustrations of the machines and some speculative drawings from the 18th and 19th centuries. -

Catapults and Trebuchets (Catapulting, Trebuchets and Physics, Oh My!)

Catapults and Trebuchets (Catapulting, Trebuchets and Physics, Oh My!) GRADE LEVELS: This workshop is for 9th through 12th grade CONCEPTS: A lever is a rigid object that can multiply the force of an another object Levers are made of different parts such as the fulcrum, effort arm, and load Levers are made of three classes Data from experiments can be translated into graphs for further study Experiments must be constantly modified for optimum results OBJECTIVES: Create catapult from various components Identify kinetic and potential energy Identify various parts of levers Use deductions made from trial runs and adjust catapult for better results Identify different classes of levers. Collect data from catapult launches and graph results ACADEMIC CONTENT STANDARDS: Science: Physical Sciences 9.21, 9.22, 9.24, 9.25, 12.5 VOCABULARY/KEY WORDS: Lever: a simple machine used to move a load using a board/arm, and fulcrum Fulcrum: the point on which a lever rotates Board/Arm: the part of the lever that force is applied to and that supports the load Force: the effort used to move the board/arm and the load Load: the mass to be moved Counterweight: a weight that balances another weight Kinetic energy: energy of motion as an object moves from one position to another Potential energy: stored energy due to an object’s position or state of matter Trebuchet: a form catapult that utilized a counterweight and sling to throw a load Catapult: a large lever used as a military machine to throw objects COSI | 333 W. Broad St. | Columbus, OH 43215 | 614.228.COSI | www.cosi.org EXTENSIONS AT COSI: Big Science Park: Giant Lever Progress: Identify various levers used in the 1898 portion of the exhibition. -

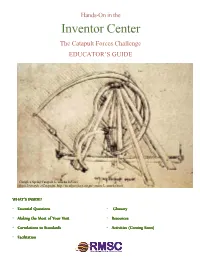

Inventor Center the Catapult Forces Challenge EDUCATOR’S GUIDE

Hands-On in the Inventor Center The Catapult Forces Challenge EDUCATOR’S GUIDE Complex Spring Catapult, Leonardo daVinci from Leonardo’s Catapults , http://members.iinet.net.au/~rmine/Leonardo.html WHATWHAT’’’’SSSS INSIDE? • Essential Questions • Glossary • Making thethethe Most ofofof Your Visit • Resources • CorrelationCorrelationssss tototo Standards • Activities (Coming Soon) • Facilitation ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS During your facilitated hands-on experience in the Inventor Center: Catapult Forces Challenge , the facilitator will be posing essential questions to your students in two categories: The In- ventive Process and the Science of Catapults and Trebuchets. These questions may also be use- ful for you as a teacher to gain background information as well as for facilitating higher order thinking during class discussions. The Inventive Process Inventor Center encourages students to explore the thrilling process of invention. The Inventor Center includes a series of participatory stations: build, experiment, learn and share. Students will define the problem, build a prototype, experiment with the prototype, learn how well the prototype works (solves the problem), and share their ideas or inventions with others. Who is an inventor? An inventor is someone who uses technology in a new way to solve a problem. An invention is a unique or novel device, method, or process. Inventions are different than discoveries because a discovery is detecting something that already ex- ists. In the Inventor Center everyone is an inventor. What is the inventive process? There are many ways to invent. Most inventive processes consist of four main parts: learning, building, testing (or exper- imenting), and sharing. These four parts of the inventive process can happen in any order. -

Military Technology in the 12Th Century

Zurich Model United Nations MILITARY TECHNOLOGY IN THE 12TH CENTURY The following list is a compilation of various sources and is meant as a refer- ence guide. It does not need to be read entirely before the conference. The breakdown of centralized states after the fall of the Roman empire led a number of groups in Europe turning to large-scale pillaging as their primary source of income. Most notably the Vikings and Mongols. As these groups were usually small and needed to move fast, building fortifications was the most efficient way to provide refuge and protection. Leading to virtually all large cities having city walls. The fortifications evolved over the course of the middle ages and with it, the battle techniques and technology used to defend or siege heavy forts and castles. Designers of castles focused a lot on defending entrances and protecting gates with drawbridges, portcullises and barbicans as these were the usual week spots. A detailed ref- erence guide of various technologies and strategies is compiled on the following pages. Dur- ing the third crusade and before the invention of gunpowder the advantages and the balance of power and logistics usually favoured the defender. Another major advancement and change since the Roman empire was the invention of the stirrup around 600 A.D. (although wide use is only mentioned around 900 A.D.). The stirrup enabled armoured knights to ride war horses, creating a nearly unstoppable heavy cavalry for peasant draftees and lightly armoured foot soldiers. With the increased usage of heavy cav- alry, pike infantry became essential to the medieval army. -

Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500 - 1605

Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500 - 1605 A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrew de la Garza Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin, Advisor; Stephen Dale; Jennifer Siegel Copyright by Andrew de la Garza 2010 Abstract This doctoral dissertation, Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, examines the transformation of warfare in South Asia during the foundation and consolidation of the Mughal Empire. It emphasizes the practical specifics of how the Imperial army waged war and prepared for war—technology, tactics, operations, training and logistics. These are topics poorly covered in the existing Mughal historiography, which primarily addresses military affairs through their background and context— cultural, political and economic. I argue that events in India during this period in many ways paralleled the early stages of the ongoing “Military Revolution” in early modern Europe. The Mughals effectively combined the martial implements and practices of Europe, Central Asia and India into a model that was well suited for the unique demands and challenges of their setting. ii Dedication This document is dedicated to John Nira. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Professor John F. Guilmartin and the other members of my committee, Professors Stephen Dale and Jennifer Siegel, for their invaluable advice and assistance. I am also grateful to the many other colleagues, both faculty and graduate students, who helped me in so many ways during this long, challenging process. -

Military Technology 203

MILITARY TECHNOLOGY 203 Military Technology 204 MILITARY TECHNOLOGY Counterweight trebuchet az-Zardkāš (1374) knows a certain form of the trebuchet called the «European catapult.» (Cat. V, 107; G 1.02) The traction trebuchet is designated as the «King's trebuchet» by az-Zardkāš (1374). (Cat. V, 106; G 1.01) Large counter balance catapult This type of siege engine seems to have been invented in the Islamic world during the 12th century ce, i.e. the era of crusades. Progres- sive features were the extended beam, wind- lasses or winches, gearing and clinometer (ballistic protractor). (Cat. V, 108; G 1.03) MILITARY TECHNOLOGY 205 Counterweight trebuchet with arrow ejector. This type of trebuchet was a sub-variety of the model Qarābu∫ā. The main difference be- tween the two was that the latter was meant to hurl heavy arrows instead of stones or other voluminous objects. (Cat. V, 110; G 1.20) Counterweight trebuchet with crossbow. This type of catapult has two functions; it hurls mis- siles as well as large arrows. It was developed in the 12th century. (Cat. V, 112; G 1.19) The large triple crossbow was popular already in the 12th century in the Arabic-Islamic culture area. (Cat. V, 114; G 1.18) The windlass crossbow was popular already in the 11th century in the Arabic-Islamic culture area. (Cat. V, 113; G 1.17) 206 MILITARY TECHNOLOGY Arab counterweight trebuchet in occidental Arab counterweight trebuchets in occidental tradition has reached Europe already in the tradition (13th cent.). 13th century from the Islamic world. Our (Cat. -

Maker Corner Activity

science fair central Maker Corner Activity CATAPULT COMPETITION! Grade Level: High School make. create. explore. www.ScienceFairCentral.com #ScienceFairCentral Do you know the difference between a catapult and a trebuchet? Overview This activity focuses on the “Designing Solutions”, “Creating Students will investigate different kinds of catapults as they or Prototyping”, “Refining and explore how counterweights and levers work to launch Improving”, and “Communicating projectiles into the air. They will then apply what they have Results” stages of the Engineering learned as they experiment with building a mini-catapult, and Design Cycle. they will work in teams to optimize its design and maximize the distance and accuracy that its projectile can be launched. Engineering Design Cycle The class will then participate in a class-wide catapult challenge, and a catapult competition champion will be y Defining the Problem crowned at the end! y Designing Solutions y Creating or Prototyping Have you ever wondered... y Refine or Improve y Communicating Results Who invented the first catapult? The catapult was invented by Dionysius the Elder of Syracuse: a Greek tyrant who had conquered Sicily and Southern Italy1. Objectives He developed the catapult in about 400 BC so it could be Students will be able to: used as a siege machine that could throw heavy objects with immense force and for long distances. His design remained Understand the goal of a simple popular throughout medieval times. Some catapults that machine. evolved from Dionysius’s invention could throw rocks that Compare how two different kinds 2 weighed up to 350 pounds more than 300 feet! of catapults function. -

Who Invented Catapults and Trebuchets?

Hands-On in the Inventor Center The Catapult Forces Challenge EDUCATOR’S GUIDE Complex Spring Catapult, Leonardo daVinci from Leonardo’s Catapults , http://members.iinet.net.au/~rmine/Leonardo.html WHATWHAT’’’’SSSS INSIDE? • Essential Questions • Glossary • Making thethethe Most ofofof Your Visit • Resources • CorrelationCorrelationssss tototo Standards • Activities (Coming Soon) • Facilitation ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS During your facilitated hands-on experience in the Inventor Center: Catapult Forces Challenge , the facilitator will be posing essential questions to your students in two categories: The In- ventive Process and the Science of Catapults and Trebuchets. These questions may also be use- ful for you as a teacher to gain background information as well as for facilitating higher order thinking during class discussions. The Inventive Process Inventor Center encourages students to explore the thrilling process of invention. The Inventor Center includes a series of participatory stations: build, experiment, learn and share. Students will define the problem, build a prototype, experiment with the prototype, learn how well the prototype works (solves the problem), and share their ideas or inventions with others. Who is an inventor? An inventor is someone who uses technology in a new way to solve a problem. An invention is a unique or novel device, method, or process. Inventions are different than discoveries because a discovery is detecting something that already ex- ists. In the Inventor Center everyone is an inventor. What is the inventive process? There are many ways to invent. Most inventive processes consist of four main parts: learning, building, testing (or exper- imenting), and sharing. These four parts of the inventive process can happen in any order. -

MORRIS HILLS REGIONAL DISTRICT Program of Studies 2018-2019

MORRIS HILLS REGIONAL DISTRICT Program of Studies 2018-2019 BOARD OF EDUCATION (2017-2018) MARK DIGENNARO ROBERT CROCETTI, JR. President Vice President Wharton Borough Rockaway Township WILLIAM SERAFIN, Rockaway Borough DOUG BROOKES, Rockaway Township MICHAEL WIECZERZAK, Rockaway Township MICHAEL BERTRAM, Denville Township ROB IZSA, Denville Township BARBARA GUERRA, Rockaway Township STEVEN KOVACS, Denville Township DISTRICT ADMINISTRATORS JAMES JENCARELLI Superintendent DR. NISHA ZOELLER JOANN AURICCHIO Assistant Superintendent Board Secretary/Business Administrator PETER LAZZARO SONYA BOYER JENNIFER TORIELLO Supervisor of District Director of Director of Instructional Services Human Resources Special Services Language Arts KEITH BIGORA DR. KEVIN DOYLE CHERYL GIORDANO Supervisor of Career & Supervisor of Instructional Services Director of Instructional Services-Math Technical Education Science /Magnet Coordinator Director for AMSE P. NEIL CHARLES MEGAN WECHSLER KRYSTAL BECK Supervisor of Technology Services Supervisor of Special Services Supervisor of Instructional Services Social Studies SCHOOL ADMINISTRATION MORRIS HILLS HIGH SCHOOL MORRIS KNOLLS HIGH SCHOOL 520 West Main Street 50 Knoll Drive Rockaway, NJ 07866-3799 Rockaway, NJ 07866-4099 PRINCIPALS TODD M. TORIELLO RYAN MACNAUGHTON ASSISTANT PRINCIPALS ROBERT M. MERLE, JR. JOSEPH CIRIGLIANO EUGENE MELVIN ERIN MORGAN EMILY BARKOCY DANIEL HAUG SUPERVISORS OF STUDENT SERVICES/ATHLETICS ROBERT D. HARAKA KENNETH M. MULLEN SUPERVISORS OF SCHOOL COUNSELING YESENIA RIVERA STAN ABROMAVAGE 1 MORRIS HILLS REGIONAL DISTRICT PROGRAM OF STUDIES 2018-2019 INTRODUCTION The Morris Hills Regional District Program of Studies has a comprehensive catalogue of more than one hundred sixty academic and vocational courses offered in grades 9 through 12 at Morris Hills High School and Morris Knolls High School. This publication has been developed especially for use as a guide in student program planning. -

Demonstration Will Recall Era When the Trebuchet Ruled Medieval Battles - 1

Demonstration will recall era when the trebuchet ruled medieval battles - 1 But despite any warts or limitations, the trebuchet is an Demonstration will recall object of fascination for history student Daniel Bertrand. And, based on the crowd of more than a 100 spectators era when the trebuchet who watched his 2017 demonstration, many more share ruled medieval battles that enchantment of history. This weekend Bertrand and his trebuchet-building team will demonstrate an improved model, from 10 a.m. to noon 10/17/2018 on Saturday, Oct. 20. The location is an empty field in Benson, 4800 N. 2400 West. Signs will direct spectators. Audiences will witness the fate of pumpkins and bowling balls as they’re launched into the distance. Bertrand, a self-described “super senior” who will graduate this spring, was first introduced to the trebuchet when he was a freshman in engineering and participated in an annual Pumpkin Toss. But with the encouragement of Dr. Susan Cogan, a medievalist and assistant professor of history, Bertrand decided to “go back to the roots of the trebuchet — how Daniel Bertrand (right) helps load the trebuchet basket they would have built it back then.” with sandbags to use as a counterweight during the 2017 Bertrand, 22 years old and a native of Taylorsville, Utah, event. At left is Cody Patton, 2017 history graduate and was already into the Middle Ages’ “knights and swords CHaSS valedictorian. and castles” when he changed his major to history. He eschews any romantic tales of chivalry, preferring “the Trebuchet demonstration: action and politics of war” — specifically, “the High Middle Ages, before the black plague.” 10 a.m.-12 noon, Saturday, Oct. -

Crusader Warfare Revisited: a Revisionist Look at R

Quidditas Volume 14 Article 3 1993 Crusader Warfare Revisited: A Revisionist Look at R. C. Smail's Thesis: Fortifications and Development of Defensive Planning Paul E. Chevedden Salem State College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, History Commons, Philosophy Commons, and the Renaissance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Chevedden, Paul E. (1993) "Crusader Warfare Revisited: A Revisionist Look at R. C. Smail's Thesis: Fortifications and Development of Defensive Planning," Quidditas: Vol. 14 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/rmmra/vol14/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Quidditas by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Crusader Warfare Revisited: A Revisionist Look at R. C. Smail's Thesis: Fortifications and Development of Defensive Planning Paul E. Chevedden alem tate College 1 The influence ofSmail's study he study of medieval military architecture - Islamic, Byzantine, western, and crusader - has received much attention, but the T major emphasis has been placed on archjtectural description. Little attention has been devoted to the study of the development of fortifications during the iddle Ages. Smail's Crusadi11g Warfare, 1097-1193 was not primarily devoted to the subject of fortifications and the development of defensive planning in the crusader states, but his comments on trus topic have been extremely influential and have served to stifle further discussion on this important subject. T he Middle Ages saw notable changes in the design of fortifications, yet Smail denies that any changes in defensive planning occurred during this period. -

Medieval Weapons of War in the Physics Curriculum

Medieval Weapons of War in the Physics Curriculum Kevin M. Crosby, Dan Lyons, Carrie Pinter, and Ann Randolph Departments of Physics, Carthage College, Kenosha, WI 53158 (Dated: June 30, 2000) Students in the introductory mechanics course at Carthage College designed and built a trebuchet, which is a medieval counterweight catapult whose history is shrouded in mystery. While there are a few surviving drawings of the device, including those of Leonardo da Vinci, its design details are largely lost. Our recreations of the trebuchet were preceded by a Newtonian analysis of three variations of the trebuchet. Students in our mechanics course apply conservation principles to the trebuchet models, and make predictions regarding the effective range of each of the three models. Experiments and computer simulations corroborate the calculations. I. INTRODUCTION In 1304 Edward I mounted a daring attack against the Castle of Stirling in Scotland for which he ordered the construction of a devastating new weapon. The siege against Castle Stirling was successful, but there are few surviving records of the design of the weapon used in the siege. Historians believe it to have been a version of what later appears in Leonardo da Vincis drawings as a tre- buchet. The trebuchet is a medieval siege weapon resem- bling a catapult, and used to launch massive projectiles at Castle walls from hundreds of yards or more. How- ever, the surviving sketches of these weapons show de- vices with impractical sizes and proportions. Was such a weapon ever built? Was the trebuchet the decisive factor in the Stirling siege? Students in our introductory and FIG.