Love Your Work: Training, Retaining and Connecting Artists in Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert Lepage's Scenographic Dramaturgy: the Aesthetic Signature at Work

1 Robert Lepage’s Scenographic Dramaturgy: The Aesthetic Signature at Work Melissa Poll Abstract Heir to the écriture scénique introduced by theatre’s modern movement, director Robert Lepage’s scenography is his entry point when re-envisioning an extant text. Due to widespread interest in the Québécois auteur’s devised offerings, however, Lepage’s highly visual interpretations of canonical works remain largely neglected in current scholarship. My paper seeks to address this gap, theorizing Lepage’s approach as a three-pronged ‘scenographic dramaturgy’, composed of historical-spatial mapping, metamorphous space and kinetic bodies. By referencing a range of Lepage’s extant text productions and aligning elements of his work to historical and contemporary models of scenography-driven performance, this project will detail how the three components of Lepage’s scenographic dramaturgy ‘write’ meaning-making performance texts. Historical-Spatial Mapping as the foundation for Lepage’s Scenographic Dramaturgy In itself, Lepage’s reliance on evocative scenography is inline with the aesthetics of various theatre-makers. Examples range from Appia and Craig’s early experiments summoning atmosphere through lighting and minimalist sets to Penny Woolcock’s English National Opera production of John Adams’s Dr. Atomic1 which uses digital projections and film clips to revisit the circumstances leading up to Little Boy’s release on Hiroshima in 1945. Other artists known for a signature visual approach to locating narrative include Simon McBurney, who incorporates digital projections to present Moscow via a Google Maps perspective in Complicité’s The Master and Margarita and auteur Benedict Andrews, whose recent production of Three Sisters sees Chekhov’s heroines stranded on a mound of dirt at the play’s conclusion, an apt metaphor for their dreary futures in provincial Russia. -

Issue 17 Ausact: the Australian Actor Training Conference 2019

www.fusion-journal.com Fusion Journal is an international, online scholarly journal for the communication, creative industries and media arts disciplines. Co-founded by the Faculty of Arts and Education, Charles Sturt University (Australia) and the College of Arts, University of Lincoln (United Kingdom), Fusion Journal publishes refereed articles, creative works and other practice-led forms of output. Issue 17 AusAct: The Australian Actor Training Conference 2019 Editors Robert Lewis (Charles Sturt University) Dominique Sweeney (Charles Sturt University) Soseh Yekanians (Charles Sturt University) Contents Editorial: AusAct 2019 – Being Relevant .......................................................................... 1 Robert Lewis, Dominique Sweeney and Soseh Yekanians Vulnerability in a crisis: Pedagogy, critical reflection and positionality in actor training ................................................................................................................ 6 Jessica Hartley Brisbane Junior Theatre’s Abridged Method Acting System ......................................... 20 Jack Bradford Haunted by irrelevance? ................................................................................................. 39 Kim Durban Encouraging actors to see themselves as agents of change: The role of dramaturgs, critics, commentators, academics and activists in actor training in Australia .............. 49 Bree Hadley and Kathryn Kelly ISSN 2201-7208 | Published under Creative Commons License (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) From ‘methods’ to ‘approaches’: -

Teacher's Notes 2007

Sydney Theatre Company and Sydney Festival in association with Perth International Festival present the STC Actors Company in The War of the Roses by William Shakespeare Teacher's Resource Kit Part One written and compiled by Jeffrey Dawson Acknowledgements Thank you to the following for their invaluable material for these Teachers' Notes: Laura Scrivano, Publications Manager,STC; Tom Wright, Associate Director, STC Copyright Copyright protects this Teacher’s Resource Kit. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited. However, limited photocopying for classroom use only is permitted by educational institutions. Sydney Theatre Company The Wars of the Roses Teachers Notes © 2009 1 Contents Production Credits 3 Background information on the production 4 Part One, Act One Backstory & Synopsis 5 Part One, Act Two Backstory & Synopsis 5 Notes from the Rehearsal Room 7 Shakespeare’s History plays as a genre 8 Women in Drama and Performance 9 The Director – Benedict Andrews 10 Review Links 11 Set Design 12 Costume Design 12 Sound Design 12 Questions and Activities Before viewing the Play 14 Questions and Activities After viewing the Play 20 Bibliography 24 Background on Part Two of The War of the Roses 27 Sydney Theatre Company The Wars of the Roses Teachers Notes © 2009 2 Sydney Theatre Company and Sydney Festival in association with Perth International Festival present the STC Actors Company in The War of the Roses by William Shakespeare Cast Act One King Richard II Cate Blanchett Production -

Chloe Armstrong

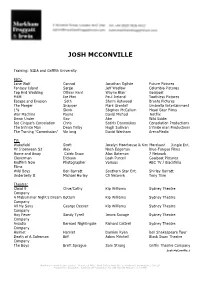

JOSH MCCONVILLE | Actor FILM Year Production / Character Director Company 2017 1% Stephen McCallum Head Gear Films Skink 2016 WAR MACHINE David Michôd Porchlight Films Payne 2015 JOE CINQUE'S CONSOLATION Sotiris Dounoukos Consolation Productions Chris 2014 DOWN UNDER Abe Forsythe Riot Films Gav 2013 THE INFINITE MAN Hugh Sullivan Infinite Man Productions P/L Dean Trilby 2012 THE TURNING “COMMISSION” David Wenham ArenaMedia Vic Lang TELEVISION Year Production/Character Director Company 2017 HOME & AWAY Various Seven Network Caleb 2015 CLEVERMAN Wayne Blair ABCTV Dickson 2013 THE KILLING FIELD Samantha Lang Seven Network Operations Jackson 2012 REDFERN NOW Various ABC TV/Blackfella Films Photographer Shanahan Management Pty Ltd Level 3 | Berman House | 91 Campbell Street | Surry Hills NSW 2010 PO Box 1509 | Darlinghurst NSW 1300 Australia | ABN 46 001 117 728 Telephone 61 2 8202 1800 | Facsimile 61 2 8202 1801 | [email protected] 2011 WILD BOYS Various Southern Star Productions No. 8 Ben 2009 UNDERBELLY II: Various Screentime A TALE OF TWO CITIES Hurley THEATRE Year Production/Character Director Company 2017 CLOUD 9 Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Clive/Cathy 2016 A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Bottom 2016 ALL MY SONS Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company George Deever 2016 HAY FEVER Imara Savage Sydney Theatre Company Sandy Tyrell 2016 ARCADIA Richard Cottrell Sydney Theatre Company Bernard Nightingale 2015 HAMLET Damien Ryan Bell Shakespeare Hamlet 2015 AFTER DINNER Imara Savage Sydney Theatre Company -

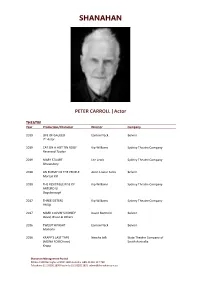

PETER CARROLL |Actor

SHANAHAN PETER CARROLL |Actor THEATRE Year Production/Character Director Company 2019 LIFE OF GALILEO Eamon Flack Belvoir 7th Actor 2019 CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Reverend Tooker 2019 MARY STUART Lee Lewis Sydney Theatre Company Shrewsbury 2018 AN ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE Anne-Louise Sarks Belvoir Morton Kiil 2018 THE RESISTIBLE RISE OF Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company ARTURO UI Dogsborough 2017 THREE SISTERS Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Phillip 2017 MARK COLVIN’S KIDNEY David Berthold Belvoir David, Bruce & Others 2016 TWELFTH NIGHT Eamon Flack Belvoir Malvolio 2016 KRAPP’S LAST TAPE Nescha Jelk State Theatre Company of (MONA FOMO tour) South Australia Krapp Shanahan Management Pty Ltd PO Box 1509 Darlinghurst NSW 1300 Australia ABN 46 001 117 728 Telephone 61 2 8202 1800 Facsimile 61 2 8202 1801 [email protected] SHANAHAN 2015 SEVENTEEN Anne-Louise Sarks Belvoir Tom 2015 KRAPP’S LAST TAPE Nescha Jelk State Theatre Company of Krapp South Australia 2014 CHRISTMAS CAROL Anne-Louise Sarks Belvoir Marley and Other 2014 OEDIPUS REX Adena Jacobs Belvoir Oedipus 2014 NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTIAN Matthew Lutton Malthouse Theatre Mr Hugo Sword 2012-13 CHITTY CHITTY BANG BANG Roger Hodgman TML Enterprises Grandpa Potts 2012 OLD MAN Anthea Williams B Sharp Belvoir (Downstairs) Albert 2011 NO MAN’S LAND Michael Gow QTC/STC Spooner 2011 DOCTOR ZHIVAGO Des McAnuff Gordon Frost Organisation Alexander 2010 THE PIRATES OF PENZANCE Stuart Maunder Opera Australia Major-General Stanley 2010 KING LEAR Marion Potts Bell -

Josh Mcconville

JOSH MCCONVILLE Training: NIDA and Griffith University Film: Lone Wolf Conrad Jonathan Ogilvie Future Pictures Fantasy Island Sarge Jeff Wadlow Columbia Pictures Top End Wedding Officer Kent Wayne Blair Goalpost M4M Ice Man Paul Ireland Toothless Pictures Escape and Evasion Seth Storm Ashwood Bronte Pictures The Merger Snapper Mark Grentell Umbrella Entertainment 1% Skink Stephen McCallum Head Gear Films War Machine Payne David Michod Netflix Down Under Gav Abe Wild Eddie Joe Cinque's Consolation Chris Sotiris Dounoukos Consolation Productions The Infinite Man Dean Trilby Hugh Sullivan Infinite man Productions The Turning "Commission" Vic lang David Wenham ArenaMedia TV: Wakefield Scott Jocelyn Moorhouse & Kim Morduant Jungle Ent. Mr Inbetween S2 Alex Nash Edgerton Blue-Tongue Films Home and Away Caleb Snow Alan Bateman 7 Network Cleverman Dickson Leah Purcell Goalpost Pictures Redfern Now Photographer Various ABC TV / Blackfella Films Wild Boys Ben Barratt Southern Star Ent. Shirley Barratt Underbelly II Michael Hurley C9 Network Tony Tilse Theatre: Cloud 9 Clive/Cathy Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company A Midsummer Night's Dream Bottom Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company All My Sons George Deever Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Hay Fever Sandy Tyrell Imara Savage Sydney Theatre Company Arcadia Bernard Nightingale Richard Cottrell Sydney Theatre Company Hamlet Hamlet Damien Ryan Bell Shakespeare Tour Death of A Salesman Biff Adam Mitchell Black Swan Theatre Company The Boys Brett Sprague Sam Strong Griffin Theatre Company Josh McConville -

Sydney Theatre Company Annual Report 2011 Annual Report | Chairman’S Report 2011 Annual Report | Chairman’S Report

2011 SYDNEY THEATRE COMPANY ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | CHAIRMAn’s RepoRT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | CHAIRMAn’s RepoRT 2 3 2011 ANNUAL REPORT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT “I consider the three hours I spent on Saturday night … among the happiest of my theatregoing life.” Ben Brantley, The New York Times, on STC’s Uncle Vanya “I had never seen live theatre until I saw a production at STC. At first I was engrossed in the medium. but the more plays I saw, the more I understood their power. They started to shape the way I saw the world, the way I analysed social situations, the way I understood myself.” 2011 Youth Advisory Panel member “Every time I set foot on The Wharf at STC, I feel I’m HOME, and I’ve loved this company and this venue ever since Richard Wherrett showed me round the place when it was just a deserted, crumbling, rat-infested industrial pier sometime late 1970’s and a wonderful dream waiting to happen.” Jacki Weaver 4 5 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | THROUGH NUMBERS 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | THROUGH NUMBERS THROUGH NUMBERS 10 8 1 writers under commission new Australian works and adaptations sold out season of Uncle Vanya at the presented across the Company in 2011 Kennedy Center in Washington DC A snapshot of the activity undertaken by STC in 2011 1,310 193 100,000 5 374 hours of theatre actors employed across the year litre rainwater tank installed under national and regional tours presented hours mentoring teachers in our School The Wharf Drama program 1,516 450,000 6 4 200 weeks of employment to actors in 2011 The number of people STC and ST resident actors home theatres people on the payroll each week attracted into the Walsh Bay precinct, driving tourism to NSW and Australia 6 7 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | ARTISTIC DIRECTORs’ RepoRT 2011 ANNUAL REPORT | ARTISTIC DIRECTORs’ RepoRT Andrew Upton & Cate Blanchett time in German art and regular with STC – had a window of availability Resident Artists’ program again to embrace our culture. -

Thorragnarok59d97e5bd2b22.Pdf

©2017 Marvel. All Rights Reserved. CAST Thor . .CHRIS HEMSWORTH Loki . TOM HIDDLESTON Hela . CATE BLANCHETT Heimdall . .IDRIS ELBA Grandmaster . JEFF GOLDBLUM MARVEL STUDIOS Valkyrie . TESSA THOMPSON presents Skurge . .KARL URBAN Bruce Banner/Hulk . MARK RUFFALO Odin . .ANTHONY HOPKINS Doctor Strange . BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH Korg . TAIKA WAITITI Topaz . RACHEL HOUSE Surtur . CLANCY BROWN Hogun . TADANOBU ASANO Volstagg . RAY STEVENSON Fandral . ZACHARY LEVI Asgardian Date #1 . GEORGIA BLIZZARD Asgardian Date #2 . AMALI GOLDEN Actor Sif . CHARLOTTE NICDAO Odin’s Assistant . ASHLEY RICARDO College Girl #1 . .SHALOM BRUNE-FRANKLIN Directed by . TAIKA WAITITI College Girl #2 . TAYLOR HEMSWORTH Written by . ERIC PEARSON Lead Scrapper . COHEN HOLLOWAY and CRAIG KYLE Golden Lady #1 . ALIA SEROR O’NEIL & CHRISTOPHER L. YOST Golden Lady #2 . .SOPHIA LARYEA Produced by . KEVIN FEIGE, p.g.a. Cousin Carlo . STEVEN OLIVER Executive Producer . LOUIS D’ESPOSITO Beerbot 5000 . HAMISH PARKINSON Executive Producer . VICTORIA ALONSO Warden . JASPER BAGG Executive Producer . BRAD WINDERBAUM Asgardian Daughter . SKY CASTANHO Executive Producers . THOMAS M. HAMMEL Asgardian Mother . SHARI SEBBENS STAN LEE Asgardian Uncle . RICHARD GREEN Co-Producer . DAVID J. GRANT Asgardian Son . SOL CASTANHO Director of Photography . .JAVIER AGUIRRESAROBE, ASC Valkyrie Sister #1 . JET TRANTER Production Designers . .DAN HENNAH Valkyrie Sister #2 . SAMANTHA HOPPER RA VINCENT Asgardian Woman . .ELOISE WINESTOCK Edited by . .JOEL NEGRON, ACE Asgardian Man . ROB MAYES ZENE BAKER, ACE Costume Designer . MAYES C. RUBEO Second Unit Director & Stunt Coordinator . BEN COOKE Visual Eff ects Supervisor . JAKE MORRISON Stunt Coordinator . .KYLE GARDINER Music by . MARK MOTHERSBAUGH Fight Coordinator . JON VALERA Music Supervisor . DAVE JORDAN Head Stunt Rigger . ANDY OWEN Casting by . SARAH HALLEY FINN, CSA Stunt Department Manager . -

Dossier De Prensa

DOSSIER DE PRENSA 1 www.madrid.org/fo XXVII FESTIVAL DE en primavera XXVIIOTOÑO festival de otoño en primavera Comunidad de Madrid XXVII festival de otoño en primavera Comunidad de Madrid XXVII festival de otoño en primavera 2 www.madrid.org/fowww.madrid.org/fo FESTIVAL DE OTOÑO CAMBIOS A PROGRAMCIÓN SUJETA EN PRIMAVERA 2010 DÍAS PASAN COSAS DÍAS PASAN Compañía Guillermo Weickert Compañía Guillermo Weickert Foto: Paloma Parra XXVII festival de otoño en primavera Comunidad de Madrid XXVII festival de otoño en primavera Comunidad de Madrid XXVII festival de otoño en primavera Comunidad de Madrid XXVII festival de otoño en primavera Comunidad de Madrid XXVII festival de otoño enprimavera 3 3 www.madrid.org/fowww.madrid.org/fo XXVII festival de en primavera OTOÑOXXVII festival de otoño en primavera Comunidad de Madrid XXVII festival de otoño en primavera Comunidad de Madrid XXVII festival de otoño en primavera 4 www.madrid.org/fo XXVII festival de otoño en primavera Índice ÍNDICE DE ESPECTÁCULOS POR ORDEN ALFABÉTICO 7 ÍNDICE DE COMPAÑÍAS POR ORDEN ALFABÉTICO 9 INTRODUCCIÓN 11 ESPECTÁCULOS 15 PROGRAMACIÓN POR ESPACIOS ESCÉNICOS 207 PROGRAMACIÓN POR ORDEN CRONOLÓGICO 213 DIRECCIONES Y PRECIOS. VENTA DE LOCALIDADES 223 XXVII FESTIVAL DE OTOÑO EN PRIMAVERA Del 12 de mayo al 6 de junio de 2010 XXVII festival de otoño en primavera Comunidad de Madrid XXVII festival de otoño en primavera Comunidad de Madrid XXVII festival de otoño en primavera Comunidad de Madrid XXVII festival de otoño en primavera Comunidad de Madrid XXVII festival de otoño en primavera 5 www.madrid.org/fo festival de en primavera OTOÑOXXVII festival de otoño en primavera Comunidad de Madrid XXVII festival de otoño en primavera Comunidad de Madrid XXVII festival de otoño en primavera 6 www.madrid.org/fo XXVII festival de otoño en primavera Índice por espectáculos 11 and 12 C.I.C.T./ THÉÂTRE DES BOUFFES DU NORD, PARIS 21 32, rue Vandenbranden PEEPING TOM 51 Al borde del agua ESCUELA DE ÓPERA DE PEKÍN 177 Bab et Sane de René Zahnd THÉÂTRE VIDY-LAUSANNE 81 BABEL (words) EASTMAN. -

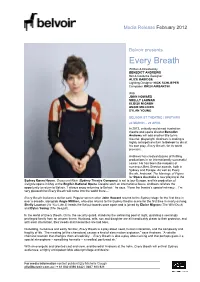

Every Breath Written & Directed by BENEDICT ANDREWS Set & Costume Designer ALICE BABIDGE Lighting Designer NICK SCHLIEPER Composer OREN AMBARCHI

Media Release February 2012 Belvoir presents Every Breath Written & Directed by BENEDICT ANDREWS Set & Costume Designer ALICE BABIDGE Lighting Designer NICK SCHLIEPER Composer OREN AMBARCHI With JOHN HOWARD SHELLY LAUMAN ELOISE MIGNON ANGIE MILLIKEN DYLAN YOUNG BELVOIR ST THEATRE | UPSTAIRS 24 MARCH – 29 APRIL In 2012, critically acclaimed Australian theatre and opera director Benedict Andrews will add another title to his résumé: playwright. Andrews is making a highly anticipated return to Belvoir to direct his own play, Every Breath, for its world premiere. Andrews has created dozens of thrilling productions in an internationally successful career. He has been the recipient of numerous Best Director awards, both in Sydney and Europe. As well as Every Breath, Andrews‟ The Marriage of Figaro for Opera Australia is now playing at the Sydney Opera House, Gross und Klein (Sydney Theatre Company) is set to tour Europe, and his production of Caligula opens in May at the English National Opera. Despite such an international focus, Andrews relishes the opportunity to return to Belvoir. „I always enjoy returning to Belvoir,‟ he says. „I love the theatre‟s special intimacy… I‟m very pleased that Every Breath will come into the world there…‟ Every Breath features a stellar cast. Popular screen actor John Howard returns to the Sydney stage for the first time in over a decade, alongside Angie Milliken, who also returns to the Sydney theatre scene for the first time in nearly as long. Shelly Lauman (As You Like It) treads the Belvoir boards once again and is joined by Eloise Mignon (The Wild Duck) and Dylan Young (The Seagull). -

The Young Vic's Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and the NT And

The National Theatre adds new productions to streaming platform: the Young Vic’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and the NT and Out of Joint’s Consent by Nina Raine • Both productions are now available on National Theatre at Home platform to stream worldwide • Cat on a Hot Tin Roof will also be available with audio-description • The NT also becomes the first performing arts organisation featured in the Bloomberg Connects app – a free digital guide to more than 20 cultural organisations around the world. Wednesday 10th March 2021 The National Theatre has today announced that two new filmed productions have been added to its streaming service National Theatre at Home: the Young Vic’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and the National Theatre and Out of Joint’s co-production Consent. The Young Vic’s 2017 West End production of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof was directed by Benedict Andrews (A Streetcar Named Desire) with Sienna Miller (21 Bridges, American Woman) as Maggie, Jack O’Connell (Unbroken, Trial by Fire) as Brick and Colm Meaney (Gangs of London) as Big Daddy. Tennessee Williams’ searing, poetic story of a family’s fight for survival is a twentieth century masterpiece. Nina Raine’s play Consent premiered in the Dorfman theatre in 2017, a co-production between the National Theatre and Out of Joint. Following a sold-out run at the National Theatre, it transferred to the Harold Pinter Theatre in 2018. The acclaimed production of this challenging and funny play features the original cast including Anna Maxwell Martin (Motherland, The Personal History of David Copperfield) and Daisy Haggard (Breeders, Back to Life). -

En/Et Presenteren / Présentent: UNA

en/et presenteren / présentent: UNA release: 12/07/2017 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Persmappen en beeldmateriaal van al onze actuele titels kan u downloaden van onze site: Vous pouvez télécharger les dossiers de presse et les images de nos films sur: https://cinemien.be/pers/films/ - https://fr.cinemien.be/presse/films/ Synopsis NL Een jonge vrouw gaat op zoek naar antwoorden. Ze brengt een onaangekondigd bezoekje aan een oude bekende op diens werkplek. De ontmoeting brengt diep begraven geheimen uit het verleden weer aan de oppervlakte en doet onuitspreekbare verlangens weer opborrelen. Hun zorgvuldig terug opgebouwde levens zullen nooit meer hetzelfde zijn. FR Quand une jeune femme, en recherche des réponses, arrive inattendue au lieu de travail d’un homme âgé, les secrets du passé peuvent bouleverser sa nouvelle vie. Leur confrontation permettra de découvrir des souvenirs enterrés et des désirs indescriptibles. Cela les secouera tous les deux au cœur. Specificaties / Spécifications duur / durée: 94 min. productie / production: UK / Royaume-Uni ondertiteling: Nederlands & Frans, dialogen in het Engels sous-titrage: néerlandais & français, dialogues en anglais formaat / format: 1.85 : 1 geluid / son: DOLBY Cast Ben Mendelsohn Ray Rooney Mara Una Ruby Stokes Young Una Roz Ahmed Scott Tobias Menzies Mark Tara Fitzgerald Andrea Poppy Corby-Tuech Poppy Natasha Little Yvonne Isobelle Molloy Holly Ciarán McMenamin John Crew regie / réalisation: Benedict Andrews scenario / scénario: