1873–1875: Carmen • 211

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Georges Bizet

Cronologia della vita e delle opere di Georges Bizet 1838 – 25 ottobre: nasce a Parigi Alexandre-César-Léopold, figlio di Adolph-Armand, modesto maestro di canto, e di Aimée-Marie Delsarte, buona pianista. Il bambino sarà poi battezzato col nome di Georges. 1847 – Frequenta come uditore il corso di pianoforte di Antoine-François Marmontel. 1848-52 – Al Conservatorio di Parigi studia contrappunto e fuga con Pierre Zimmermann, allievo di Cherubini; segue anche qualche lezione con Charles Gounod, che influisce fortemente sulla sua formazione. Sviluppa le doti di pianista continuando a studiare nella classe di Marmontel e ottiene diversi premi riservati agli allievi. 1853 – Alla morte di Zimmermann, frequenta i corsi di composizione di Jacques Halévy. 1854 – Prime composizioni: Grande valse de concert in mi bemolle maggiore e Nocturne in fa maggiore. 1855 – Ouverture in la minore, Sinfonia in do maggiore, Valse in do maggiore per coro e orchestra. 1856 – È secondo al Prix de Rome con la cantata David . 1857 – L’operetta in un atto Le Docteur Miracle , vincitrice (ex equo con Charles Lecocq) di un premio offerto da Offenbach, debutta con successo al Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens. Con la cantata Clovis et Clotilde il compositore si aggiudica il Prix de Rome: può così godere per cinque anni di una sovvenzione statale e soggiornare per due anni in Germania e in Italia. 1858 – In gennaio raggiunge Roma. Si stabilisce a Villa Medici, sede italiana dell’Académie Française che ospita i vincitori del Prix de Rome. Scrive un Te Deum e in estate va in vacanza sui Colli Albani. Musica un libretto di soggetto italiano, Don Procopio , che invia all’Académie Française. -

The Art of Music :A Comprehensive Ilbrar

1wmm H?mi BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT or Hetirg W, Sage 1891 A36:66^a, ' ?>/m7^7 9306 Cornell University Library ML 100.M39 V.9 The art of music :a comprehensive ilbrar 3 1924 022 385 342 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924022385342 THE ART OF MUSIC The Art of Music A Comprehensive Library of Information for Music Lovers and Musicians Editor-in-Chief DANIEL GREGORY MASON Columbia UniveTsity Associate Editors EDWARD B. HILL LELAND HALL Harvard University Past Professor, Univ. of Wisconsin Managing Editor CESAR SAERCHINGER Modem Music Society of New Yoric In Fourteen Volumes Profusely Illustrated NEW YORK THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC Lillian Nordica as Briinnhilde After a pholo from life THE ART OF MUSIC: VOLUME NINE The Opera Department Editor: CESAR SAERCHINGER Secretary Modern Music Society of New York Author, 'The Opera Since Wagner,' etc. Introduction by ALFRED HERTZ Conductor San Francisco Symphony Orchestra Formerly Conductor Metropolitan Opera House, New York NEW YORK THE NASTIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC i\.3(ft(fliji Copyright, 1918. by THE NATIONAL SOCIETY OF MUSIC, Inc. [All Bights Reserved] THE OPERA INTRODUCTION The opera is a problem—a problem to the composer • and to the audience. The composer's problem has been in the course of solution for over three centuries and the problem of the audience is fresh with every per- formance. -

The Opera: a Brief Overview

The Opera: a brief overview Emilio Sala The most reliable experts swear that the opera is the most widely performed in the world. However, when it was first staged at the Opéra-Comique in Paris on 3 March 1875, it was given a rather frosty reception. The fact that the public did not understand it was a cause of deep sorrow to Bizet, who died three months later at the age of only thirty-six. Even so, Carmen ran for 48 consecutive performances, which can hardly be considered a negligible figure, although ironically, the audiences were drawn by the opera’s reputed indecency and its condemnation by the press. “Our stages are increasingly invaded by courtesans. This is the class from which our authors so like to re - cruit the heroines of their dramas and their opéras-comiques ”, wrote Achille de Lauzières in his review published in La Patrie on 8 March. He went on: “It is the fille in the most repugnant sense of the word [that has been set on stage]; the fille who is obsessed with her body, who gives herself to the first soldier that passes, on a whim, as a dare, blindly; […] sensual, mocking, hard-faced; miscreant, obedient only to the law of pleasure; […] in short, well and truly a prostitute off the streets”. The critic for the Petit Journal on 6 March said of the interpretation of Carmen: “Madame Galli-Marié has found how to make the character of Carmen more vulgar, more hateful and more abject than it already was in Mérimée. Her interpretation is brutally re - alistic, in the manner of Courbet”. -

Ernest Guiraud: a Biography and Catalogue of Works

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1990 Ernest Guiraud: A Biography and Catalogue of Works. Daniel O. Weilbaecher Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Weilbaecher, Daniel O., "Ernest Guiraud: A Biography and Catalogue of Works." (1990). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4959. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4959 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 Is Approved in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

DEVELOPING THE YOUNG DRAMATIC SOPRANO VOICE AGES 15-22 By Monica Ariane Williams Bachelor of Arts – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1993 Master of Music – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1995 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2020 Copyright 2021 Monica Ariane Williams All Rights Reserved Dissertation Approval The Graduate College The University of Nevada, Las Vegas November 30, 2020 This dissertation prepared by Monica Ariane Williams entitled Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music Alfonse Anderson, DMA. Kathryn Hausbeck Korgan, Ph.D. Examination Committee Chair Graduate College Dean Linda Lister, DMA. Examination Committee Member David Weiller, MM. Examination Committee Member Dean Gronemeier, DMA, JD. Examination Committee Member Joe Bynum, MFA. Graduate College Faculty Representative ii ABSTRACT This doctoral dissertation provides information on how to develop the young dramatic soprano, specifically through more concentrated focus on the breath. Proper breathing is considered the single most important skill a singer will learn, but its methodology continues to mystify multitudes of singers and voice teachers. Voice professionals often write treatises with a chapter or two devoted to breathing, whose explanations are extremely varied, complex or vague. Young dramatic sopranos, whose voices are unwieldy and take longer to develop are at a particular disadvantage for absorbing a solid vocal technique. First, a description, classification and brief history of the young dramatic soprano is discussed along with a retracing of breath methodologies relevant to the young dramatic soprano’s development. -

Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Friday Evening, February 20, 2015, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor MAX VON SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa ACT I Intermission ACT II Foreigner/Francesco del Giocondo: MICHAEL ANTHONY MCGEE, Bass-baritone Woman/Mona Fiordalisa: PETRA MARIA SCHNITZER, Soprano Lay Brother/Giovanni de Salviati: PAUL MCNAMARA, Tenor Pietro Tumoni: JUSTIN HOPKINS, Bass-baritone Arrigo Oldofredi: ROBERT CHAFIN, Tenor Alessio Beneventi: JOHN EASTERLIN, Tenor Sandro da Luzzano: CHRISTOPHER BURCHETT, Baritone Masolino Pedruzzi: MICHAEL SCARCELLE, Bass-baritone Mona Ginevra: ILANA DAVIDSON, Soprano Dianora: LUCY FITZ GIBBON, Soprano Piccarda: KATHERINE MAYSEK, Mezzo-soprano Sisto: JOHN KAWA, Tenor BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This evening’s concert will run approximately two hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition Vienna, publisher and copyright owner. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes the many organizations who participate in our Community Access Program, which provides free and low-cost tickets to underserved groups in New York’s five boroughs. For information on how you can support this program, please call (212) 868-9276. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director The Stolen Smile DVDs or pirated videos. Opera is the by Leon Botstein one medium from the past that resists technological reproduction. A concert This concert performance of Max von version still represents properly the Schillings’ 1915 Mona Lisa is the latest sonority and the multi-dimensional installment of a series of concert perfor- aspect crucial to the operatic experi- mances of rare operas the ASO has pio- ence. -

Saint-Saëns Voyageur L’Ailleurs Est Un Puissant Moteur

Les colloques de l’Opéra Comique Exotisme et art lyrique. Juin 2012 Sous la direction d’Alexandre DRATWICKI et Agnès TERRIER Saint-Saëns voyageur L’ailleurs est un puissant moteur Marie-Gabrielle SORET Saint-Saëns disait de lui-même : « Le juif errant était un sédentaire à côté de moi1 », ou encore : « J’ai la réputation d’un nomade2. » Cette réputation était bien justifiée ; entre janvier et août 1912 par exemple, le musicien a parcouru 25 000 km, et c’est ainsi à peu près tous les ans depuis le début des années 1870. Ses confrères s’en étonnent, les journaux s’en amusent3 et se font souvent l’écho de ses déplacements. Saint-Saëns est un très grand voyageur et rien, ni son grand âge, ni la dégradation de son état de santé, ne ralentiront le rythme de ses pérégrinations. Mais quelles motivations, quels « moteurs », l’ont donc poussé à mener cette vie de perpétuelle transhumance, à rechercher sans cesse un « ailleurs » – et ce jusqu’à son dernier souffle, puisqu’il s’éteint dans un hôtel d’Alger, le 16 décembre 1921, à l’âge de 86 ans. Comment ces voyages ont-ils marqué l’homme et influencé l’œuvre ? La première explication que met en avant Saint-Saëns pour justifier ces longues absences, est une raison de santé. Les voyages sont pour lui quasiment une condition nécessaire à sa survie. Il est en effet phtisique depuis l’enfance, maladie héritée de son père, Jacques-Victor Saint-Saëns, mort à 37 ans, à peine trois mois après la naissance de ce fils unique. -

Phd April 2019 Pp

The University of Adelaide Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Arts Revisiting George Enescu’s 1921 Bucharest Recital Series: a performance-based investigation with recordings and exegesis. by Elizabeth Layton submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Adelaide, April 2019 Table of Contents Abstract 5 Declaration 6 Acknowledgements 7 List of Musical Examples 8 List of Tables 11 Introduction 12 PART A: Sound recordings 22 A.1 CD 1 Tracks 1-4 Pierre de Bréville, Sonata no. 1 in C # minor 39:17 Tracks 5-8 Gabriel Fauré, Sonata no. 1 in A major, Op. 13 26:14 A.2 CD 2 Tracks 1-4 André Gédalge, Sonata no. 1 in G major, Op. 12 23:39 Tracks 5-7 Claude Debussy, Sonata in G minor (performance 1) 13:44 Tracks 8-10 Claude Debussy, Sonata in G minor (performance 2) 13:36 A.3 CD 3 Tracks 1-3 Ferruccio Busoni, Sonata no. 2 in E minor, Op. 36a 34:25 Tracks 4-7 Zygmunt Stojowski, Sonata no. 2 in E minor, Op. 37 29:30 A.4 CD 4 Tracks 1-4 Louis Vierne, Sonata in G minor, Op. 23 32:44 Tracks 5-7 Stan Golestan, Sonata in E flat major 26:56 Tracks 8-10 George Enescu, Sonata in F minor, Op. 6 22:34 PART B: Exegesis Chapter 1 George Enescu: Musician, and his path to the 1921 Bucharest Recital Series 27 1.1 Understanding the context and motivation behind the series 35 2 Chapter 2 The 1921 Bucharest Recital Series 38 2.1 Recital 1: Haydn, d’Indy, Bertelin 38 2.2 Recital 2: Mozart, Busoni, Vierne 39 2.3 Recital 3: Sjögren, Schubert, Lauweryns 41 2.4 Recital 4: Weingartner, Stojowski, Beethoven 42 2.5 Recital 5: Bargiel, Haydn, Golestan 42 2.6 Recital 6: Le Boucher, Mozart, Saint-Saëns 43 2.7 Recital 7: Gédalge, Dvorák, Debussy, Schumann 44 2.8 Recital 8: Huré, Bach, Lekeu 45 2.9 Recital 9: Beethoven, Fauré, Franck 46 2.10 Recital 10: Gallon, de Bréville, Beethoven 48 2.11 Recital 11: Magnard, Le Flem, Brahms 49 2.12 Recital 12: Franck, Enescu, Beethoven 49 Chapter 3 Performance notes on nine sonatas selected from the 1921 Bucharest Recital Series 3.1 Pierre de Bréville, Sonata no. -

Program Notes by Dr

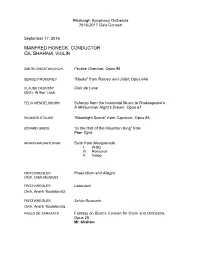

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Gala Concert September 17, 2016 MANFRED HONECK, CONDUCTOR GIL SHAHAM, VIOLIN DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Festive Overture, Opus 96 SERGEI PROKOFIEV “Masks” from Romeo and Juliet, Opus 64a CLAUDE DEBUSSY Clair de Lune Orch. Arthur Luck FELIX MENDELSSOHN Scherzo from the Incidental Music to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Opus 61 RICHARD STAUSS “Moonlight Scene” from Capriccio, Opus 85 EDVARD GREIG “In the Hall of the Mountain King” from Peer Gynt ARAM KHACHATURIAN Suite from Masquerade I. Waltz IV. Romance V. Galop FRITZ KREISLER Praeludium and Allegro Orch. Clark McAlister FRITZ KREISLER Liebesleid Orch. André Kostelanetz FRITZ KREISLER Schön Rosmarin Orch. André Kostelanetz PABLO DE SARASATE Fantasy on Bizet’s Carmen for Violin and Orchestra, Opus 25 Mr. Shaham Sept. 17, 2016, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) Festive Overture, Opus 96 (1954) Among the grand symphonies, concertos, operas and chamber works that Dmitri Shostakovich produced are also many occasional pieces: film scores, tone poems, jingoistic anthems, brief instrumental compositions. Though most of these works are unfamiliar in the West, one — the Festive Overture — has been a favorite since it was written in the autumn of 1954. Shostakovich composed it for a concert on November 7, 1954 commemorating the 37th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but its jubilant nature suggests it may also have been conceived as an outpouring of relief at the death of Joseph Stalin one year earlier. One critic suggested that the Overture was “a gay picture of streets and squares packed with a young and happy throng.” As its title suggests, the Festive Overture is a brilliant affair, full of fanfare and bursting spirits. -

Benjamin Godard Sonates Pour Piano Et Violon Benjamin Godard (1849-1895)

Nicolas Dautricourt Dana Ciocarlie Benjamin Godard Sonates pour piano et violon Benjamin Godard (1849-1895) CD1 CD2 Sonate pour piano et violon no 3 Sonate pour piano et violon no 4 en sol mineur, op. 9 en la bémol majeur, op. 12 Piano & Violin Sonata No. 3 in G minor Piano & Violin Sonata No. 4 in A-flat major 1. Allegro moderato 8’41 1. Vivace ma non troppo 7’53 Enregistré à la Salle Byzantine du Palais de Béhague (Paris) du 2 au 4 septembre 2015. 2. Scherzo (non troppo vivace) 3’58 2. Allegro vivace ma non presto 4’10 Remerciements : Palazzetto Bru Zane, l’équipe de l’Ambassade de Roumanie en République Française 3. Andante 4’50 3. Andante 7’02 et Pierre Malbos. 4. Intermezzo 4. Allegro molto 6’47 Production exécutive et son : Little Tribeca (un poco moderato) 2’57 Direction artistique et ingénieur du son : Clément Rousset 5. Allegro 5’26 Piano CFX YAMAHA no 6315200 Sonate pour piano et violon no 2 Préparation et accord : Pierre Malbos Sonate pour piano et violon no 1 en la mineur, op. 2 Photos artistes © Bernard Martinez en do mineur, op. 1 Piano & Violin Sonata No. 2 in A minor Piano & Violin Sonata No. 1 in C minor 5. Andante - Allegro Couverture © Bnf English translation © Sue Rose 6. Andante-Allegro 5’32 vivace e appassionato 7’16 7. Scherzo (molto moderato) 3’00 6. Intermezzo (vivace) 2’02 Aparté · Little Tribeca 8. Andante 4’59 7. Andante quasi adagio 4’16 1, rue Paul Bert 93500 Pantin, France AP124 © ℗ Little Tribeca - Palazzetto Bru Zane 2015 9. -

![FALL, L.: Rose Von Stambul (Die) (The Rose of Stambul) [Operetta] 8.660326-27](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6931/fall-l-rose-von-stambul-die-the-rose-of-stambul-operetta-8-660326-27-1296931.webp)

FALL, L.: Rose Von Stambul (Die) (The Rose of Stambul) [Operetta] 8.660326-27

FALL, L.: Rose von Stambul (Die) (The Rose of Stambul) [Operetta] 8.660326-27 http://www.naxos.com/catalogue/item.asp?item_code=8.660326-27 Leo Fall (1873-1925) Die Rose von Stambul (The Rose of Stambul) Operetta in Three Acts Libretto by Robert Bodanzky (1879-1923) (English translation by Hersh Glagov and Gerald Frantzen, edited by Bill Walters) Kondja Gül. Kimberly McCord, Soprano Midili Hanum. Alison Kelly, Soprano Fridolin Müller . Erich Buchholz, Tenor Achmed Bey. Gerald Frantzen, Tenor Mr. Müller Sr. Robert Morrissey, Bass Bül-bül / Durlane . Sarah Bockel, Mezzo-soprano Fatme . Malia Ropp, Soprano Emine. Julia Tarlo, Soprano Djamileh . Nicole Hill, Soprano Güzela. Khaki Pixely, Mezzo-soprano Desirée. Michelle Buck, Soprano Kemal Pasha . Chris Guerra, Baritone Bell Hop . Eric Casady, Baritone Hotel Director. Aaron Benham, Tenor Band Leader . Josh Prisching, Baritone The Chorus is formed of members of the cast Act I (A brief DANCE. The WOMEN hum and play while BÜLBÜL and Setting: Stambul (Istanbul) DJAMILEH dance. The music continues after the dance is finished. At the end, all the WOMEN come to KONDJA’s door and bow.) A small, elegant ladies’ salon in KEMAL PASHA’S palace during the last years of the Ottoman Empire. Very luxuriously furnished, like the rooms of Scene 2 a young European lady. In the background are several rectangular Desireé, Bülbül and Harem Women windows, which, though covered with grillwork, reveal a glorious panorama of Stambul (Istanbul) with its mosques and minarets in magical sunlight. To Desireé the right is a door that leads to the daughter’s bedroom. Above the (Enters from upstage door) bedroom door is a quote from the Koran, embroidered in gold on velvet. -

Mikhail Bugaev DMA Document

PAUL HINDEMITH’S IDIOMATIC WRITING FOR VIOLA AND ITS INFLUENCE ON HIS THEORIES. SONATA FOR VIOLA SOLO OP. 11, NO. 5. By Mikhail Bugaev A DOCUMENT Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS Music 2013 Table of contents: INTRODUCTION____________________________________________________________________________3 I. HINDEMITH’S PERFORMANCE CAREER 1. Successful violinist, early stage of Hindemith as a violist__________________4 2. Amar-Hindemith Quartet, and a peak of a performance career___________6 3. Last stage of a Hindemith-performer, Der Schwanendreher_______________8 4. Conclusion___________________________________________________________________12 II. SONATA OP. 11 NO. 5 1. History of the genre and influences________________________________________14 2. Structural and thematic analysis of the movements______________________19 3. Idiomatic writing____________________________________________________________35 a. The link to the instrument b. Motive as a building block c. Chords and intervals 4. Conclusion___________________________________________________________________42 III. INSTRUMENTAL APPROACH TO THE THEORIES 1. Series 1 and 2________________________________________________________________44 2. Intervalic content____________________________________________________________47 3. Melody________________________________________________________________________48 CONCLUSION_____________________________________________________________________________49 BIBLIOGRAPHY__________________________________________________________________________51