Featured Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Deutscher Bundestag

Deutscher Bundestag 198. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Donnerstag, 18.Oktober 2012 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 1 Artikel 3 des Gesetzentwurfs der Bundesregierung Entwurf eines Achten Gesetzes zur Änderung des Gesetzes gegen Wettbewerbsbeschränkungen (8. GWB-ÄndG) in der Ausschussfassung Drs. 17/9852 und 17/11053 Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 543 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 77 Ja-Stimmen: 302 Nein-Stimmen: 241 Enthaltungen: 0 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 18. Okt. 12 Beginn: 19:24 Ende: 19:26 Seite: 1 CDU/CSU Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg.Name Ilse Aigner X Peter Altmaier X Peter Aumer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Günter Baumann X Ernst-Reinhard Beck (Reutlingen) X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Dr. Christoph Bergner X Peter Beyer X Steffen Bilger X Clemens Binninger X Peter Bleser X Dr. Maria Böhmer X Wolfgang Börnsen (Bönstrup) X Wolfgang Bosbach X Norbert Brackmann X Klaus Brähmig X Michael Brand X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Helmut Brandt X Dr. Ralf Brauksiepe X Dr. Helge Braun X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Cajus Caesar X Gitta Connemann X Alexander Dobrindt X Thomas Dörflinger X Marie-Luise Dött X Dr. Thomas Feist X Enak Ferlemann X Ingrid Fischbach X Hartwig Fischer (Göttingen) X Dirk Fischer (Hamburg) X Axel E. Fischer (Karlsruhe-Land) X Dr. Maria Flachsbarth X Klaus-Peter Flosbach X Herbert Frankenhauser X Dr. Hans-Peter Friedrich (Hof) X Michael Frieser X Erich G. Fritz X Dr. Michael Fuchs X Hans-Joachim Fuchtel X Alexander Funk X Ingo Gädechens X Dr. Peter Gauweiler X Dr. -

Deutscher Bundestag

Deutscher Bundestag 44. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Freitag, 27.Juni 2014 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 4 Entschließungsantrag der Abgeordneten Caren Lay, Eva Bulling-Schröter, Dr. Dietmar Bartsch, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE. zu der dritten Beratung des Gesetzentwurfs der Bundesregierung Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur grundlegenden Reform des Erneuerbare-Energien-Gesetzes und zur Änderung weiterer Bestimmungen des Energiewirtschaftsrechts - Drucksachen 18/1304, 18/1573, 18/1891 und 18/1901 - Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 575 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 56 Ja-Stimmen: 109 Nein-Stimmen: 465 Enthaltungen: 1 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 27.06.2014 Beginn: 10:58 Ende: 11:01 Seite: 1 Seite: 2 Seite: 2 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Stephan Albani X Katrin Albsteiger X Peter Altmaier X Artur Auernhammer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Julia Bartz X Günter Baumann X Maik Beermann X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Sybille Benning X Dr. Andre Berghegger X Dr. Christoph Bergner X Ute Bertram X Peter Beyer X Steffen Bilger X Clemens Binninger X Peter Bleser X Dr. Maria Böhmer X Wolfgang Bosbach X Norbert Brackmann X Klaus Brähmig X Michael Brand X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Helmut Brandt X Dr. Ralf Brauksiepe X Dr. Helge Braun X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Cajus Caesar X Gitta Connemann X Alexandra Dinges-Dierig X Alexander Dobrindt X Michael Donth X Thomas Dörflinger X Marie-Luise Dött X Hansjörg Durz X Jutta Eckenbach X Dr. Bernd Fabritius X Hermann Färber X Uwe Feiler X Dr. Thomas Feist X Enak Ferlemann X Ingrid Fischbach X Dirk Fischer (Hamburg) X Axel E. -

Protokoll Vom 7.10.2010 Einbringung Des 1

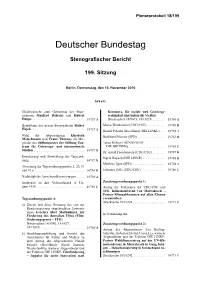

Plenarprotokoll 17/65 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 65. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 7. Oktober 2010 Inhalt: Wahl des Abgeordneten Siegmund Ehrmann Serkan Tören (FDP) . 6806 A als ordentliches Mitglied im Kuratorium der Stiftung „Haus der Geschichte der Bundes- Volker Beck (Köln) (BÜNDNIS 90/ republik Deutschland“ . 6791 A DIE GRÜNEN) . 6806 C Wahl des Abgeordneten Dr. h. c. Wolfgang Josef Philip Winkler (BÜNDNIS 90/ Thierse als ordentliches Mitglied und des Ab- DIE GRÜNEN) . 6808 A geordneten Dietmar Nietan als stellvertreten- Stefan Müller (Erlangen) (CDU/CSU) . des Mitglied im Stiftungsrat der „Stiftung 6809 B Flucht, Vertreibung, Versöhnung“ . 6791 B Daniela Kolbe (Leipzig) (SPD) . 6810 C Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Sibylle Laurischk (FDP) . 6812 A nung . 6791 B Reinhard Grindel (CDU/CSU) . 6812 C Absetzung der Tagesordnungspunkte 5 a, b und d . 6792 D Tagesordnungspunkt 4: Tagesordnungspunkt 3: Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Barbara Höll, Unterrichtung durch die Beauftragte der Bun- Dr. Axel Troost, Richard Pitterle, weiterer desregierung für Migration, Flüchtlinge und Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE: Integration: Achter Bericht über die Lage Auswege aus der Krise: Steuerpolitische der Ausländerinnen und Ausländer in Gerechtigkeit und Handlungsfähigkeit des Deutschland Staates wiederherstellen (Drucksache 17/2400) . 6792 D (Drucksache 17/2944) . 6813 D Dr. Maria Böhmer, Staatsministerin Dr. Barbara Höll (DIE LINKE) . 6814 A BK . 6793 A Olav Gutting (CDU/CSU) . 6816 A Olaf Scholz (SPD) . 6795 D Nicolette Kressl (SPD) . 6818 A Hartfrid Wolff (Rems-Murr) (FDP) . 6797 B Dr. Volker Wissing (FDP) . 6820 C Harald Wolf, Senator (Berlin) . 6798 C Matthias W. Birkwald (DIE LINKE) . 6821 A Memet Kilic (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) . -

Hate Crime Report 031008

HATE CRIMES IN THE OSCE REGION -INCIDENTS AND RESPONSES ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2007 Warsaw, October 2008 Foreword In 2007, violent manifestations of intolerance continued to take place across the OSCE region. Such acts, although targeting individuals, affected entire communities and instilled fear among victims and members of their communities. The destabilizing effect of hate crimes and the potential for such crimes and incidents to threaten the security of individuals and societal cohesion – by giving rise to wider-scale conflict and violence – was acknowledged in the decision on tolerance and non-discrimination adopted by the OSCE Ministerial Council in Madrid in November 2007.1 The development of this report is based on the task the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) received “to serve as a collection point for information and statistics on hate crimes and relevant legislation provided by participating States and to make this information publicly available through … its report on Challenges and Responses to Hate-Motivated Incidents in the OSCE Region”.2 A comprehensive consultation process with governments and civil society takes place during the drafting of the report. In February 2008, ODIHR issued a first call to the nominated national points of contact on combating hate crime, to civil society, and to OSCE institutions and field operations to submit information for this report. The requested information included updates on legislative developments, data on hate crimes and incidents, as well as practical initiatives for combating hate crime. I am pleased to note that the national points of contact provided ODIHR with information and updates on a more systematic basis. -

Nein-Stimmen: 32 Enthaltungen: 13 Ungültige: 0

Deutscher Bundestag 89. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Freitag, 27.Februar 2015 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 1 Antrag des Bundesministeriums der Finanzen Finanzhilfen zugunsten Griechenlands; Verlängerung der Stabilitätshilfe Einholung eines zustimmenden Beschlusses des Deutschen Bundestages nach § 3 Abs. 1 i.V.m. § 3 Abs. 2 Nummer 2 des Stabilisierungsmechanismusgesetzes auf Verlängerung der bestehenden Finanzhilfefazilität zugunsten der Hellenischen Republik Drs. 18/4079 und 18/4093 Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 586 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 45 Ja-Stimmen: 541 Nein-Stimmen: 32 Enthaltungen: 13 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 27.02.2015 Beginn: 11:05 Ende: 11:10 Seite: 1 Seite: 2 Seite: 2 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Stephan Albani X Katrin Albsteiger X Peter Altmaier X Artur Auernhammer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Günter Baumann X Maik Beermann X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Sybille Benning X Dr. Andre Berghegger X Dr. Christoph Bergner X Ute Bertram X Peter Beyer X Steffen Bilger X Clemens Binninger X Peter Bleser X Dr. Maria Böhmer X Wolfgang Bosbach X Norbert Brackmann X Klaus Brähmig X Michael Brand X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Helmut Brandt X Dr. Ralf Brauksiepe X Dr. Helge Braun X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Cajus Caesar X Gitta Connemann X Alexandra Dinges-Dierig X Alexander Dobrindt X Michael Donth X Thomas Dörflinger X Marie-Luise Dött X Hansjörg Durz X Jutta Eckenbach X Dr. Bernd Fabritius X Hermann Färber X Uwe Feiler X Dr. Thomas Feist X Enak Ferlemann X Ingrid Fischbach X Dirk Fischer (Hamburg) X Axel E. -

Plenarprotokoll 18/136

Textrahmenoptionen: 16 mm Abstand oben Plenarprotokoll 18/136 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 136. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 12. November 2015 Inhalt: Würdigung von Bundeskanzler a. D. Helmut Tagesordnungspunkt 5: Schmidt. 13233 A Antrag der Abgeordneten Sabine Zimmermann (Zwickau), Ulla Jelpke, Jutta Krellmann, wei- Erweiterung der Tagesordnung ............ 13234 D terer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE: Flüchtlinge auf dem Weg in Arbeit Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisung ...... 13235 A unterstützen, Integration befördern und Lohndumping bekämpfen Begrüßung des Vorsitzenden des Auswär- Drucksache 18/6644 .................... 13250 A tigen Ausschusses des Europäischen Par- laments, Herrn Elmar Brok, und des Gene- Sabine Zimmermann (Zwickau) ralsekretärs der OSZE, Herrn Lamberto (DIE LINKE) ....................... 13250 B Zannier .............................. 13266 C Karl Schiewerling (CDU/CSU) ........... 13251 D Brigitte Pothmer (BÜNDNIS 90/ Tagesordnungspunkt 4: DIE GRÜNEN) ...................... 13253 C Vereinbarte Debatte: 60 Jahre Bundeswehr. 13235 B Katja Mast (SPD) ...................... 13254 C Henning Otte (CDU/CSU) ............... 13235 B Dr. Matthias Zimmer (CDU/CSU) ......... 13255 C Wolfgang Gehrcke (DIE LINKE) .......... 13236 D Sevim Dağdelen (DIE LINKE) ............ 13257 A Rainer Arnold (SPD) .................... 13238 A Kerstin Griese (SPD) ................... 13258 B Agnieszka Brugger (BÜNDNIS 90/ Brigitte Pothmer (BÜNDNIS 90/ DIE GRÜNEN) .................... DIE GRÜNEN) ..................... -

BT-Drs. 14/2151

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 14/2151 14. Wahlperiode 23. 11. 99 Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des Innenausschusses (4. Ausschuss) zu dem Gesetzentwurf der Abgeordneten Dr. Evelyn Kenzler, Roland Claus, Ulla Jelpke, Sabine Jünger, Heidemarie Lüth, Petra Pau, Dr. Gregor Gysi und der Fraktion der PDS – Drucksache 14/1129 – Entwurf eines Gesetzes über Volksinitiative, Volksbegehren und Volksentscheid (dreistufige Volksgesetzgebung) A. Problem Meinungsumfragen signalisieren eine zunehmende Politik-, Politi- ker- und Parteienverdrossenheit. Viele Bürger beklagen fehlende bzw. unzureichende Möglichkeiten, unmittelbarer in den politischen Prozess eingreifen zu können, wenn sie ihre Interessen nicht oder nicht ausreichend berücksichtigt sehen. Sie fühlen sich mehr als Objekte der parlamentarischen Demokratie denn als Subjekte demo- kratischer Willensbildung. So macht das Wort von der „Zuschauer- demokratie“ die Runde. Repräsentative parlamentarische Demokratie ist unabdingbar, aber auch entwicklungs- und ergänzungsbedürftig. Ohne eine Ergänzung durch Elemente der unmittelbaren Demokratie – dies ist eine Grundstimmung, die sich besonders in den Jahren nach der Vereinigung Deutschlands verstärkt und gefestigt hat – sind die Bürgerinnen und Bürger mit der parlamentarischen Demokratie unzufrieden. Der Wunsch der Bevölkerung nach direkter Mitwirkung an der Gesetzgebung ist durch demoskopische Umfragen sowie die bereits bestehende Praxis in den einzelnen Bundesländern belegt. Dieser Wille, über Sachfragen auch selbst zu entscheiden, findet im bestehenden -

Ergebnisse Der Bundestagswahlen 2009 Und 2013 ‹ › Ergebnisse Der Bundestagswahlen 2009 Und 2013 ‹

Ergebnisse in den Wahlkreisen bei den Bundestagswahlen am Bremer Abgeordnete im Deutschen Bundestag 27.09.2009 und am 22.09.2013 im Land Bremen Im 18. Deutschen Bundestag (2013 bis 2017) ist das Land Bremen mit Gegenstand der 2009 2013 2009 2013 sechs Abgeordneten vertreten: Nachweisung Anzahl Prozent » Dr. Carsten Sieling (MdB 2009 bis 2015) SPD-Direktbewerber im Wahlkreis 54 Bremen I (2009: Wahlkreis 55) Wahlkreis 54 Wahlberechtigte 256 131 256 547 x x » Uwe Beckmeyer (MdB seit 2002) SPD-Direktbewerber im Wahlkreis 55 Wähler / Wahlbeteiligung 188 189 184 512 73,5 71,9 » Elisabeth Motschmann (MdB seit 2013) CDU-Landeslistenbewerberin Statistisches Landesamt Bremen » Marieluise Beck (MdB seit 1994) GRÜNE-Landeslistenbewerberin Ungültige Erststimmen 2 557 2 128 1,4 1,2 » Agnes Alpers (MdB 2009 bis 2015) DIE LINKE-Landeslistenbewerberin An der Weide 14-16 Gültige Erststimmen 185 632 182 384 98,6 98,8 » Bettina Hornhues (MdB seit 2013) CDU-Landeslistenbewerberin 28195 Bremen darunter SPD 62 588 69 161 33,7 37,9 » Sarah Ryglewski (MdB seit 2015) SPD-Nachfolge für Dr. Carsten Sieling Telefon: +49 421 / 361-25 01 E-Mail: [email protected] Ungültige Zweitstimmen 2 099 1 816 1,1 1,0 » Birgit Menz (MdB seit 2015) DIE LINKE-Nachfolge für Agnes Alpers Gültige Zweitstimmen 186 090 182 696 98,9 99,0 www.wahlen.bremen.de davon www.statistik.bremen.de SPD 52 387 60 502 28,2 33,1 Ergebnisse in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland bei den Bundestags- CDU 46 284 55 254 24,9 30,2 wahlen am 27.09.2009 und am 22.09.2013 Straßenbahn/Bus: Haltestelle Hauptbahnhof -

Plenarprotokoll 18/199

Plenarprotokoll 18/199 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 199. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 10. November 2016 Inhalt: Glückwünsche zum Geburtstag der Abge- Kommerz, für soziale und Genderge- ordneten Manfred Behrens und Hubert rechtigkeit und kulturelle Vielfalt Hüppe .............................. 19757 A Drucksachen 18/8073, 18/10218 ....... 19760 A Begrüßung des neuen Abgeordneten Rainer Marco Wanderwitz (CDU/CSU) .......... 19760 B Hajek .............................. 19757 A Harald Petzold (Havelland) (DIE LINKE) .. 19762 A Wahl der Abgeordneten Elisabeth Burkhard Blienert (SPD) ................ 19763 B Motschmann und Franz Thönnes als Mit- glieder des Stiftungsrates der Stiftung Zen- Tabea Rößner (BÜNDNIS 90/ trum für Osteuropa- und internationale DIE GRÜNEN) ..................... 19765 C Studien ............................. 19757 B Dr. Astrid Freudenstein (CDU/CSU) ...... 19767 B Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Sigrid Hupach (DIE LINKE) ............ 19768 B nung. 19757 B Matthias Ilgen (SPD) .................. 19769 A Absetzung der Tagesordnungspunkte 5, 20, 31 und 41 a ............................. 19758 D Johannes Selle (CDU/CSU) ............. 19769 C Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisungen ... 19759 A Gedenken an den Volksaufstand in Un- Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 1: garn 1956 ........................... 19759 C Antrag der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD: Klimakonferenz von Marrakesch – Pariser Klimaabkommen auf allen Ebenen Tagesordnungspunkt 4: vorantreiben Drucksache 18/10238 .................. 19771 C a) -

Identification of Victims of Trafficking in Human Beings in International Protection and Forced Return Procedures

Identification of victims of trafficking in human beings in international protection and forced return procedures Focussed Study of the German National Contact Point for the European Migration Network (EMN) Working Paper 56 Ulrike Hoffmann Co-financed by the European Union Identification of victims of trafficking in human beings in international protection and forced return procedures Focussed Study of the German National Contact Point for the European Migration Network (EMN) Ulrike Hoffmann Federal Office for Migration and Refugees 2013 Abstract 5 Abstract This study focuses on the identification of victims of Police and counselling centres are brought in early human trafficking from third countries in the asylum on suspected cases in order to guarantee adequate process and in the event of forced return, including care for victims and initiate criminal proceedings general conditions under criminal, asylum and resi- against the perpetrators. Social workers working dence law. The study also highlights the administrative with these counselling centres also attend to vic- mechanisms for identifying victims used by the Feder- tims of human trafficking in reception centres and al Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF), reception detention facilities. centres, detention facilities, the German Federal Police, foreigners authorities and counselling centres for vic- Residence permits issued under Section 25, Subs. tims of human trafficking. Finally, the study addresses 4a AufenthG have increased slightly. Statistics the challenges in identifying victims and presents also show that the majority of identified victims available statistics of human trafficking in Germany. of human trafficking in international protection procedures are female, between the ages of 18 and The German Penal Code (StGB) addresses various 35. -

Gesamt 3. Namabst. 08.07

Seite: 1 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Ilse Aigner X Peter Altmaier X Peter Aumer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Günter Baumann X Ernst-Reinhard Beck (Reutlingen) X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Dr. Christoph Bergner X Peter Beyer X Steffen Bilger X Clemens Binninger X Peter Bleser X Dr. Maria Böhmer X Wolfgang Börnsen (Bönstrup) X Wolfgang Bosbach X Norbert Brackmann X Klaus Brähmig X Michael Brand X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Helmut Brandt X Dr. Ralf Brauksiepe X Dr. Helge Braun X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Cajus Caesar X Gitta Connemann X Alexander Dobrindt X Thomas Dörflinger X Marie-Luise Dött X Dr. Thomas Feist X Enak Ferlemann X Ingrid Fischbach X Hartwig Fischer (Göttingen) X Dirk Fischer (Hamburg) X Axel E. Fischer (Karlsruhe-Land) X Dr. Maria Flachsbarth X Klaus-Peter Flosbach X Herbert Frankenhauser X Dr. Hans-Peter Friedrich (Hof) X Michael Frieser X Erich G. Fritz X Dr. Michael Fuchs X Hans-Joachim Fuchtel X Alexander Funk X Ingo Gädechens X Dr. Peter Gauweiler X Dr. Thomas Gebhart X Norbert Geis X Alois Gerig X Eberhard Gienger X Seite: 2 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Michael Glos X Josef Göppel X Peter Götz X Dr. Wolfgang Götzer X Ute Granold X Reinhard Grindel X Hermann Gröhe X Michael Grosse-Brömer X Markus Grübel X Manfred Grund X Monika Grütters X Olav Gutting X Florian Hahn X Dr. Stephan Harbarth X Jürgen Hardt X Gerda Hasselfeldt X Dr. Matthias Heider X Helmut Heiderich X Mechthild Heil X Ursula Heinen-Esser X Frank Heinrich X Rudolf Henke X Michael Hennrich X Jürgen Herrmann X Ansgar Heveling X Ernst Hinsken X Peter Hintze X Christian Hirte X Robert Hochbaum X Karl Holmeier X Franz-Josef Holzenkamp X Joachim Hörster X Anette Hübinger X Thomas Jarzombek X Dieter Jasper X Dr. -

Plenarprotokoll 17/165

Inhaltsverzeichnis Plenarprotokoll 17/165 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 165. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 8. März 2012 Inhalt: Wahl des Abgeordneten Stefan Liebich als verdienen mehr – Entgeltdiskriminie- ordentliches Mitglied in das Kuratorium der rung von Frauen verhindern „Stiftung Archiv der Parteien und Massen- (Drucksache 17/8897) . 19518 A organisationen der DDR“ . 19517 B e) Unterrichtung durch die Bundesregierung: Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Erster Gleichstellungsbericht nung . 19517 B Neue Wege – Gleiche Chancen Gleichstellung von Frauen und Män- Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisung . 19517 C nern im Lebensverlauf (Drucksache 17/6240) . 19518 A f) Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des Tagesordnungspunkt 3: Rechtsausschusses zu dem Antrag der Ab- a) Antrag der Abgeordneten Dorothee Bär, geordneten Cornelia Möhring, Diana Golze, Markus Grübel, Nadine Schön, weiterer Agnes Alpers, weiterer Abgeordneter und Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der CDU/ der Fraktion DIE LINKE: Geschlechter- CSU gerechte Besetzung von Führungsposi- sowie der Abgeordneten Miriam Gruß, tionen der Wirtschaft Nicole Bracht-Bendt, Florian (Drucksachen 17/4842, 17/8830) . 19518 B Bernschneider, weiterer Abgeordneter und Dr. Kristina Schröder, Bundesministerin der Fraktion der FDP: Geschlechterge- BMFSFJ . 19518 C rechtigkeit im Lebensverlauf (Drucksache 17/8879) . 19517 D Dagmar Ziegler (SPD) . 19519 C b) Antrag der Fraktionen CDU/CSU, SPD, Nicole Bracht-Bendt (FDP) . 19521 B FDP und BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN: Yvonne Ploetz (DIE LINKE) . 19522 C Gleichberechtigung in Entwicklungs- ländern voranbringen Renate Künast (BÜNDNIS 90/ (Drucksache 17/8903) . 19517 D DIE GRÜNEN) . 19524 A c) Antrag der Abgeordneten Angelika Graf Ingrid Fischbach (CDU/CSU) . 19526 A (Rosenheim), Wolfgang Gunkel, Dr. h. c. Christel Humme (SPD) . 19527 C Gernot Erler, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der SPD: Anerkennung und Patrick Döring (FDP) .