Resource Management in the Baltic Sea - a Background Document and a Summary of Findings of an International Workshop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communications Report of Special Procedures*

United Nations A/HRC/18/51 General Assembly Distr.: General 9 September 2011 English/French/Spanish only Human Rights Council Eighteenth session Agenda item 5 Human rights bodies and mechanisms Communications Report of Special Procedures* Communications sent, 1 December 2010 to 31 May 2011; Replies received, 1 February 2011 to 31 July 2011 Joint report by the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living, and on the right to non-discrimination in this context; the Working Group on arbitrary detention; the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Cambodia; the Special Rapporteur on the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography; the Independent Expert in the field of cultural rights; the Special Rapporteur on the right to education; the Working Group on enforced or involuntary disappearances; the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions; the Special Rapporteur on the right to food; the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression; the Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association; the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression; the Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief; the Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health; the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders; -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

Greetings from MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY and Meals on Wheels July 5 July 6 July 7 July 8 July 9 It’S July and the Middle of Able to Process Information

ARENA: Meals Cooked On Site. Serving at Noon. Call Candy at (608) 341-6859. S.U.N. AVOCA: Home Delivery Only, Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Call (608) 930-9845. NUTRITION CENTERS HIGHLAND: Meals provided by Betsy’s Restaurant. Call Naomi at (608) 929-7482. Senior Dining HOLLANDALE: Meals provided by Viking Café in Blanchardville. Call (608) 523-4327. Greetings from MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY and Meals on Wheels July 5 July 6 July 7 July 8 July 9 It’s July and the middle of able to process information. Medical JULY Italian Sausage Cobb Salad: Tilapia Scampi summer. We are ready to attention is needed with severe dehydration, INDEPENDENCE DAY on a Hard Roll w/Peppers, Bacon, Egg, Chicken, Pork Roast w/Applesauce Linguini w/Butter, get back to some degree since it can lead to confusion, kidney failure, OBSERVED Onions & Sauce Blue Cheese, Avocado, Scalloped Potatoes Parsley & Parmesan of normalcy, which makes heart problems and possibly death. It is also Potato Wedges Mixed Greens Sliced Carrots Peas me very happy. On July possible to become overhydrated. Although NO MEALS Black Bean Salad & Ranch Dressing Rye Roll Fresh Spinach Salad 2021 MENUS 29, we will return to our not as common, athletes and individuals SERVED Black Forest Cake Seasonal Fruit Pineapple Tidbits Blueberry Lemon annual steak cookout. All with certain medical conditions are at higher w/Cherries Sugar Cookie Frozen Dessert Suggested Donations: $5.00 Congregate and $5.50 Home Delivery of the participants and the risk. Confusion and seizures can occur. July 12 July 13 July 14 July 15 July 16 Cecile McManus, RD staff look forward to this Many factors affect how much water you HIGHLAND: Call Naomi at (608) 929-7482. -

IKEA Food Alternative Meatball DDD 2019

IKEA Food Services AB Malmö, June 4, 2019 IKEA to make tasty food more sustainable with no-meat protein meatball IKEA develops a new plant-based protein version of the iconic Swedish meatball, with the ambition to make it just as (or even more) famous as the meaty one. A first prototype will be offered to visitors at Democratic Design Days in June. Until 2050 it’s estimated that the protein consumption in the world will double due to a fast-growing population. The global demand for food will increase by 70 per cent, and the protein production of today cannot meet this demand. This leads to a high demand for alternatives to meat and seafood, and IKEA wants to do its shared part to offer healthier, tasty and more sustainable food choices. The plant-based meatball is one step on this longer journey. “At IKEA, we are constantly exploring new opportunities in creating a more sustainable future. We want to move towards more plant-based, and low impact foods served to our guests. Lower impact and plant-based ingredients are more sustainable than for instance red meat and pork”, says Michael La Cour, Managing Director at IKEA Food Services AB. The new meatball is made by plant-based alternative proteins, and the ingredients include amongst others pea protein and pea starch, potato flakes, oats and apple. The ambition is that it should be just as tasty as the meat variant, typically served with mashed potatoes, lingonberries and cream sauce. Several tests have been carried out and prototypes have been made in close collaboration with suppliers and chefs. -

Eat, Live, Pray: a Celebration of Zarathushti Culture and Cuisine © 2012 Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America (FEZANA)

Eat, Live, Pray: A celebration of Zarathushti culture and cuisine © 2012 Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America (FEZANA) www.fezana.org For free distribution You are free to use the content of this publication for personal and not-for-profit purposes. Please attribute the source if you share any information from it in print and/or electronic media including social media. ISBN: 978-0-9826871-2-3 Cover and layout: Hukhta Publications - [email protected] Every effort has been made to use illustrations that are free or from the public domain. Copyright infringement is not intended; please let us know if there is a copyright issue and we will rectify it. CONGRATULATIONS, FEZANA The Federation of the Zoroastrian Association of North America (FEZANA) was registered in the State of Illinois, USA, on June 2, 1987 as a non-profit, religious and charitable organization. In the twenty-five years since them FEZANA has had many accomplishments. In July 1996, we undertook a "Strategic Planning" exercise (FEZANA Journal, Fall 1996) which identified four collective goals for the community and the organization. One of the goals was “a thousand points of light” aimed at preserving our community’s religious and cultural entity. This publication, “Eat, Live, Pray: A celebration of Zarathushti culture and cuisine” upholds this goal. Food plays a very important role in our Zarathushti psyche. We create all varieties of food for different occasions; special food for happy occasions and we also have food for the dead in our religious ceremonies. In the Summer, 2011 edition of the FEZANA Journal, Sarosh and Benafsha Khariwala together with Arnavaz Chubb, all in Melbourne, Australia, explored the concept of “Food as Our Identity”. -

5-1-Index.Pdf

INDEX. P...o;e. Page.. AhagudM~ ..tt Point, MlIin8 ..•......---_..719, 7~O AI<)wivel;, .,awb of, in Rappaha.unock Rhm:_._... 644 Aberdel"o Packing Company •- -- . _.. _. _... 74" <)·loRe·t.imefor ._ .. _._ .•...•.. 7:.!7 Acetic aciil for pre~erviogbai1. -. _. - :{~,(! dried -. '." " --- .. --- _. 720 AcipouMPr o.xyrh.y-:n(',u~ ~ . __ . __ .. _ ~ ~ _. __ ~ .. _. _. t)?4 lir~--R"'lt"<i - .. - -. - '" .. 709 st\lY;;'~) ~ ~ '\7~ r. •• , T • _ •• -- • l69"7 t<w cod hu,i.t, ..... - __ ...... __ m:l, ~:\C ACll"lloet J<iver, thlwl'Ic9 of.... __ .• - •....•• _. ____ 661'l malllll'e .... __ . ___ ...•..••.... _ 720 Allrnodoc, name for corl .... .. __ - ... - __ .... _.. _ 21# fonner abunda.llell of -." . -. -- .. _" .. _ 6\)9 Aillik, Lahrador _.....•..•.............•. 134.1;:1:") ba.IJil>! of '" _ BH.CJ Akut.a.n Pll"-~, Ala~kll, cml hank.'>t, _. __ " _.. 21:) itl Buzzard's Ba~' - .•••. "" .. 60'2 of~ ~ ~ Alnban13t 111l11h\t fish ... r.} .. -. --_ _r ____ 577 Cape 1"(,ar Riv<'l' - .. ' ....•. --. __ __ 626 A IUf'lka, nlHllHlaUN) of eml at. _......•. _ 2117 l\lain" _..••.•.•. _•• _ _. 1i7A "ml fisher.)' of. ..... __ .--_._.. t :21, 19i<, 20(1 MerriIIlul' River - _'. _. 6i3 fj~hilJ~·groundll of _..•..••.. _•• __ ... " 21:! MOllon,o," wdr!l -..•....•.... _. 60'2 memorial (,ollcerning: ...••..••••.• _. _ . _.. :!11 Pamlil.:o Sound. .. .. .. .. •••• .. .. 6:ID native fishermen of _., _..•. --. 22(1 pouud·nut" .••••...•-.. ....•. .... .... 609 ~ahn"ll hllluBtry, statist,ie~ of ...••. _..... 753 S",nte,\ River ••. --... --- --- -. "" _... 6~4 AIbemad" SOUIIU, fisheril'8 of .....'" ." .•..•-. -

Feeding Ecology of the Arctic Ice-Amphipod Gammarus Wilkitzkii

aroiin E. Arndt private address: Hochallee 108 D - 20149 Hamburg Die vorliegende Arbeit ist die im wesentlichen unverändert Fassung einer Diplomarbeit, die in der Sektion Arctic Biology der University Courses on Svalbard (UNIS)bei Dr. Ole Jargen Lanne angefertigt und im Mai 2001 dem Fachbereich Biologie der UniversitäHamburg Prof. Angelika Brandt und Prof. Hartmut Kausch vorgelegt wurde. 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 . Gammarus wilkitzkii 1.2. Purpose of this study 2. MATERIALAND METHODS 2.1. Field work Sampling area Sampling methods Ice conditions and hydrography 2.1 1. Laboratory work 2.11.1. Physiological study Oxygen consumption 2.11.2. Behavioural observations Food detection, seeking behaviour, and localisation Food type and quantity Grooming behaviour Interactions with the abiotic and biotic environment 2.11.3. Morphological study Mouth parts and accessory feeding appendages Sensory apparatus 3. RESULTS 15 3.1. Field work Ice conditions and hydrography 15 Ice maps 16 3.1.1. Traps 17 3.11. Laboratory work 17 3.11.1 . Physiological study 17 Standard respiration 17 Respiration after Stimulation with food 19 Comparison between size classes and individual variability 21 3.11.2. Behavioural observations 22 Food detection, seeking behaviour, and localisation 22 Food type and quantity 28 Grooming behaviour 30 Interactions with the abiotic and biotic environment 31 3.11.3. Morphological study 34 Mouth Parts and accessory feeding appendages 34 4. DISCUSSION 4.1. Field work 4.1.1. Number of attracted amphipods and abundances 4.11. Laboratory work 4.11.1. Physiological study 4.11.2. Behavioural observations 4.11.3. Morphological study Gammarus wilkitzkii is a presumed omnivorous amphipod that lives in high densities in close association with Arctic pack-ice. -

I Quanartv Publicadon 01 Iha Nova Scoda Bini Sociatv NOVA SCOTIA BIRD SOCIETY Executive 2004-2005

Nova Scotia Birds I Quanartv Publicadon 01 Iha Nova Scoda Bini Sociatv NOVA SCOTIA BIRD SOCIETY Executive 2004-2005 President Suzanne Borkowski Vice President Bill Billington Past President Andy Horn Treasurer Bernice Moores Secretary Pat McKay Membership Secretary Eileen Billington Editor Blake Maybank Director Joan Czapalay Director Barbara Hinds Director Hans Toom Solicitor Tony Robinson Auditor Harold Forsyth Formed in 1955, the Nova Scotia Bird Society is a member of the Federation of Nova Scotia Naturalists and the Canadian Nature Federation. The activities of the Society are centered on the observation and study of the bird life of this province and the preservation of habitat. Nova Scotia Bird Society Rare Bird Alert: http://groups.yahoo.com/group/NS-RBA/ do Nova Scotia Museum, Email: [email protected] 1747 Summer Street, Web: http://nsbs.chebucto.org Halifax, N.S. 83H 3A6 Reporting Deadlines Winter 2006 issue: Dec. 7, 2005 Summer 2005 issue: June 7, 2005 Spring 2006 issue: Mar. 7, 2006 Fall 2005 issue: Aug. 7, 2005 Inside This Issue Fine Focus • Atlantic Canada - An Ecological Update 2 Winter Bird Reports 4 President's Comer 25 Weather & Other Reports • Wmter Weather 26 2004 - 2005 Christmas Bird Counts 29 Field Trip Reports 44 Coming Events 46 Cover Photo: This AMERICAN WIDGEON is an original work by Dartmouth artist William Duggan. www.williamduggan.com Volume 4 7, Issue 2 NOVA SCOTIA BIRDS NOVA SCOTIA BIRDS SPRING 2005 Editor Blake Maybank Production Assistant THE SPOTTING SCOPE Sterling Levy Happy Spring Birding to All Records Editor Lance Laviolette Another packed issue to send to you all, so let us not further delay. -

Low-Phosphorus Commercial Wet Foods

22833 Bothell-Everett Hwy #159 Bothell, WA 98021 Phone: (425) 489-1484 Fax: (425) 483-3009 Low Phosphorus Standard Commercial Wet Foods Calories Foods marked * are minimums for protein and in (per oz. Phosphorus Protein Carbs some cases phosphorus canned food) Rayne Clinical Nutrition Adult Health RSS 0.51 53.59 20.13 26.57 Wellness Healthy Indulgence Morsels Chicken & Chicken 0.55 37.87 23.01 20.67 Liver Wellness Healthy Indulgence Morsels with Chicken & 0.56 39.86 21.04 20.67 Salmon Hill's Science Diet Adult Tender Chicken Dinner 0.57 40.80 29.80 28.36 Hill's Science Diet Adult 7+ Tender Chicken Dinner 0.57 40.80 29.80 28.36 Weruva Truluxe Steak Frites 0.57 61.90 7.50 24.00 Nature’s Logic Beef 0.58 47.20 1.23 40.91 Wellness Divine Duos With Beef Pâté & Diced Chicken Liver 0.59 32.11 21.52 25.36 Soulistic Harvest Sunrise Chicken & Pumpkin Dinner in 0.59 56.47 27.81 21.33 Gravy Hill’s Ideal Balance Crafted Simmered Salmon Chowder 0.60 34.30 35.30 26.21 with Quinoa Hill’s Ideal Balance Crafted Savory Chicken Pot Pie with 0.60 34.40 34.90 24.83 Buckwheat Hill's Science Diet Adult 7+ Savory Turkey Entrée 0.60 34.50 34.50 29.00 Hill’s Ideal Balance Crafted Roasted Tuna & Vegetable 0.60 34.90 37.30 25.86 Medley Hill's Science Diet Adult Healthy Cuisine Roasted Chicken & 0.60 35.30 34.20 23.57 Rice Medley Dr. -

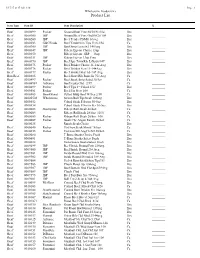

Product List

8/17/17 at 17:14:11.20 Page: 1 Wholesome Foodservice Product List Item Type Item ID Item Description X Beef 0000099 Packer Ground Beef Fine 80/20 Frz10# Lbs. ________ Beef 0000100 IBP Ground Beef Fine Grd 80/20 10# Lbs. ________ Beef 0000200 IBP Beef Tender PSMO 6#avg Lbs. ________ Beef 0000203 G&CFoods Beef Tenderloin Tips Frzn 2/5# Cs. ________ Beef 0000300 IBP Beef Strip Loin 0x1 14#Avg Lbs. ________ Beef 0000349 IBP Ribeye Lip-on Choice 13up Lbs. ________ Beef 0000350 Ribeye Lip-on IBP 13up Lbs. ________ Beef 0000351 IBP Ribeye Lip-on 13up Frzn Lbs. ________ Beef 0000370 IBP Beef Spc Trim(Rib Lifter)6/14# Lbs ________ Beef 0000375 Packer Beef Brisket Choice 11-14# Avg Lbs. ________ Beef 0000376 Packer Beef Brisket Frzn 11-14#Avg Lbs. ________ Beef 0000377 Packer Beef Brisket Flat 65-70# Avg Lbs. ________ Box Beef 0000385 Beef Short Rib Bone-In 75# Avg Cs ________ Beef 0000497 Packer Beef Steak Strip Salad 30/5oz Cs. ________ Beef 00004981 Advance Beef Fajita Ckd 2/5# Cs ________ Beef 0000499 Packer Beef Tips 1" Cubed 2/5# Lbs. ________ Beef 0000501 Packer Beef For Stew 10# Cs. ________ Beef 0000505 Brookwood Pulled BBQ Beef W/Sce 2/5# Cs. ________ Beef 00005502 Wholesome Sirloin Ball Tip Steak 10#avg Lbs ________ Beef 0000552 Cubed Steak F/Swiss 30-5oz Lbs. ________ Beef 0000554 Cubed Steak F/Swiss Frz 30-5oz Lbs. ________ Beef 0000603 Stockyards Ribeye Roll Steak 40/4oz Cs. ________ Beef 0000604 Ribeye RollSteak 28/6oz 10.5# Cs. -

Suomen Kalat

Suomen kalat HELSINGFORS, G. W. EDLUNDS FÖRLAG. XI PUBLISHED BY G. W. EDLUND HELSINGFORS. Gadus morrhua (L). TORSK. TURSKA. Plansch XXXI Gadus callarias Linné, Syst. Nat, Ed. X, T. I, p. 252 (forma minor). „ „ Bloch, Fische Deutsohl. 11, p. 109, T. 63. „ Retzius, Faun. Svec. I, p. 318. Faber, Fisclie Isl. p. 109. Ekström, Fische v. Mörkö,p. 230. „ „ v. Wright, Fries et Ekstöm, Skand Fiskar IX, p. 191. Jordan et Gilbert, Syn. Fishes North America p. 804. „ Lilljeborg, Sveriges o. Norges Fiskar p. 31. Gadus morrhua Linné, 1. c (forma typica). „ Bloch, 1. c. 11, p. 145, T. 64. Retzius, 1. c. „ Faber, 1. c. p. 104. Kröyer,Damn. Fiske 11, p. 1, Günther, Cat Fishes Brit. Mus. IV, p. 328 Malmgren, Finl. Fiskfauna, p 27. Collet, Norges Fiske p. 103. „ „ Malm, Göteb. o. Bohus]. Fauna p. 480. Winter, Prodr. Icht Dan. Mar. p. 27. Beneeke, Fische O. u. Westpreussen p. 87. „ Moreau, Poiss. France p 235. Mela, Vert. Fenn p. 298. Day, Fishes of Great Brit a. Irl. 11, p. 275, T. LXXVIII. Möbius v. Heincke, Fische der Ostsee p. 72. Gadus barbatus Linné, Faun. Svec. p. 112. „ Retzius, 1. c p. 319. Gadus morrhua et callarias Nilsson, Skand. Fauna, Fiskarna p. 537. Morrhua callarias Cuv., Regne anim. Yarrel, Brit. Fishes, Ed. 111, P. I, p. 524. Gadus ruber (Lacep.) Holböll, Göth. Vet. nya Handl. IV, p 31 (varietas). Gadus macrocephalus Tiles, Mém. acad. S:t Petersb. 1810, 11, p. 350, T. XVI (monstrositas). TORSK. TURSKA. THE COMMON COD. Denna allmänna och för fisket så betydelsefullafiskart företer This common and for fishery so important species exhibits efter olika åldrar och lokaler åtskilliga växlingar iform och färg. -

The Cod Family and Its Utilization

The Cod Family and Its Utilization JOHN J. RYAN Figure I.-Atlantic cod. Introduction without dried cod, for ships could carry cod, Gadus macrocephalus; 6) Atlantic no perishable food as staples. cod, Gadus morhua morhua; 7) Green Spanish explorers came to the New The cod family, from an economic land cod, Gadus ogac; 8) cusk, Brosme World to find gold and precious stones, point of view, is the most important of brosme; 9) fourbeard rockling, En but the French and Portuguese, fol all the families of fishes. The members chelyopus cimbrius; 10) burbot, Lota lowed by the English, crossed the At of the cod family are second only to the Iota; 11) haddock, Melanogrammus lantic to catch fish, especially the Atlan herring family in volume of commer aeglefinus; 12) silver hake (whiting), tic cod, Gadus morhua. In the 16th cial landings (Table 1). In contrast to Merluccius bilinearis; 13) Pacific hake, century, French and Portuguese vessels the herring family, which is often used Merluccius productus; 14) longfin fished the Grand Bank off Newfound for industrial purposes, almost all hake, Phycis chesteri; 15) luminous land. By the early 17th century, the of the cod, haddock, hakes, and whit hake, Steindachneria argentea; 16) red New England colonists were fishing for ings are used for human food. In hake, Urophycis chuss; 17) Gulf hake, cod (Fig. 1) in the local waters. In 1624 1976, 12,116,000 metric tons (t) Urophycis cirratus; 18) Carolina hake, "not less than 50 vessels from Glouces (26,710,000,000 pounds) of the cod Urophycis earlli; 19) southern hake, ter" fished with handlines off the coast.