Wind Farm Development in New Zealand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Renewable Energy Grid Integration in New Zealand, Tokyo, Japan

APEC EGNRET Grid Integration Workshop, 2010 Renewable Energy Grid Integration in New Zealand Workshop on Grid Interconnection Issues for Renewable Energy 12 October, 2010 Tokyo, Japan RDL APEC EGNRET Grid Integration Workshop, 2010 Coverage Electricity Generation in New Zealand, The Electricity Market, Grid Connection Issues, Technical Solutions, Market Solutions, Problems Encountered Key Points. RDL APEC EGNRET Grid Integration Workshop, 2010 Electricity in New Zealand 7 Major Generators, 1 Transmission Grid owner – the System Operator, 29 Distributors, 610 km HVDC link between North and South Islands, Installed Capacity 8,911 MW, System Generation Peak about 7,000 MW, Electricity Generated 42,000 GWh, Electricity Consumed, 2009, 38,875 GWh, Losses, 2009, 346 GWh, 8.9% Annual Demand growth of 2.4% since 1974 RDL APEC EGNRET Grid Integration Workshop, 2010 Installed Electricity Capacity, 2009 (MW) Renew able Hydro 5,378 60.4% Generation Geothermal 627 7.0% Wind 496 5.6% Wood 18 0.2% Biogas 9 0.1% Total 6,528 73.3% Non-Renew able Gas 1,228 13.8% Generation Coal 1,000 11.2% Diesel 155 1.7% Total 2,383 26.7% Total Generation 8,91 1 100.0% RDL APEC EGNRET Grid Integration Workshop, 2010 RDL APEC EGNRET Grid Integration Workshop, 2010 Electricity Generation, 2009 (GWh) Renew able Hydro 23,962 57.0% Generation Geothermal 4,542 10.8% Wind 1,456 3.5% Wood 323 0.8% Biogas 195 0.5% Total 30,478 72.6% Non-Renew able Gas 8,385 20.0% Generation Coal 3,079 7.3% Oil 8 0.0% Waste Heat 58 0.1% Total 11,530 27.4% Total Generation 42,008 1 00.0% RDL APEC EGNRET Grid Integration Workshop, 2010 Electricity from Renewable Energy New Zealand has a high usage of Renewable Energy • Penetration 67% , • Market Share 64% Renewable Energy Penetration Profile is Changing, • Hydroelectricity 57% (decreasing but seasonal), • Geothermal 11% (increasing), • 3.5% Wind Power (increasing). -

NZ Geomechanics News June 2005 NEW ZEALAND GEOMECHANICS NEWS

Newsletter of the New Zealand Issue 69 Geotechnical Society Inc. 1SSN 0111–6851 NZ Geomechanics News June 2005 NEW ZEALAND GEOMECHANICS NEWS JUNE 2005, ISSUE 69 CONTENTS Chairman’s Corner . 2 Editorial Good Reasons to be Good - P Glassey . 3 Letters to the Editor . 4 Editorial Policy. 4 Report from the Secretary . 6 International Society Reports ISSMGE . 7 IAEG . 8 ISRM . 10 ISRM - Rocha Medal . 11 ISRM - National Group website . 12 NZGS Branch Activities . 13 Conference Adverts . 20 Reviews Degrees of Belief. 23 Mapping in Engineering Geology . 24 Geotechnical Engineering Education . 25 Project News Banda Aceh - 8 Weeks After Disaster Struck . 26 Strengthening Ngaio Gorge Road Walls . 34 Te Apiti Wind Farm: Megawatt-class Machines aided by Geotechnical Expertise. 37 Geotechnical Investigations and Testing for Wellington Inner City Bypass . 40 Standards, Law and Industry News Why doesn’t New Zealand have a Geotechnical Database? . 42 Breaking News 18 May rainstorm Damage, Bay of Plenty . 43 Technical Articles Numerical Analysis in Geotechnical Engineering Final Part . 44 The Bob Wallace Column . 49 Company Profiles Keith Gillepsie Associates . 50 Boart Longyear Drillwell . 52 Member Profiles Merrick Taylor . 54 Ann Williams . 55 Events Diary . 57 New Zealand Geotechnical Society Inc Information . 60 New Zealand Geotechnical Society Inc Publications 2005 . 63 Advertising Information . 64 Cover photo: Landslide debris, Tauranga as a result of the 18 May 2005 rainstorm Photo Credit: Mauri McSaveney, GNS New Zealand Geomechanics News CHAIRMAN’S -

Meridian Energy ERU 03-06 PDD Stage 2 Final

Te Apiti Wind Farm Project (Previously the Lower North Island Wind Project) Project Design Document ERUPT 3 Project: Te Apiti Wind Farm Project (Previously Lower North Island Wind Project) Reference: ERU 03/06 Document: Baseline Study Version: 2 Programme: ERUPT 3 Stage 2 Date: August 2003 1 PROJECT DETAILS 1.1 Project characteristics Supplier Company name Meridian Energy Limited Address 15 Allen Street Zip Code & City Address Wellington Postal Address PO Box 10-840 Zip Code & City Postal Address Wellington Country New Zealand Contact Person Ms Tracy Dyson Job Title Sustainable Energy and Climate Change Advisor Tele phone Number +64 4 381 1271 Fax Number +64 4 381 1201 E-mail [email protected] Bank/Giro Number Upon Request Bank WestpacTrust No. of Employees 202 Company’s Main Activity Electricity Generation, Retailing, Trading CPV Number WN/938552 Registration Number Professional or Trade Not Applicable Register Date of Registration 17th March 1999 Local contacts and other parties involved The local contact will be Meridian Energy Ltd who will be the project owner, project manager and project developer. Te Apiti Wind Farm Project Design Document 2003 Page 2 of 67 Confidential 20th August 2003 1.2 Project Abstract Project Title Te Apiti Wind Farm Host country New Zealand Abstract Meridian Energy, New Zealand’s largest generator of electricity from renewable resources and a state owned enterprise would like to develop a wind generation project in the lower North Island of New Zealand. This project is called the Te Apiti Wind Farm and will have a capacity of between 82.5-96.25 MW. -

Meridian Energy

NEW ZEALAND Meridian Energy Performance evaluation Meridian Energy equity valuation Macquarie Research’s discounted cashflow-based equity valuation for Meridian Energy (MER) is $6,531m (nominal WACC 8.6%, asset beta 0.60, TGR 3.0%). Forecast financial model A detailed financial model with explicit forecasts out to 2030 has been completed and is summarised in this report. Inside Financial model assumptions and commentary Performance evaluation 2 We discuss a number of key model input assumptions in the report including: Valuation summary 6 Wholesale and retail electricity price paths; Financial model assumptions 8 Electricity purchase to sales price ratio pre and post the HVDC link upgrade; Financial statements summary 18 HVDC link charging regime; Financial flexibility and generation Electricity demand growth by customer type; development 21 The impact of the Electricity Industry Act (EIA) asset transfer and VAS’; Sensitivities 22 The New Zealand Aluminium Smelters (NZAS) supply contract; Alternative valuation methodologies 23 Relative disclosure 24 MER’s generation development pipeline. Appendix – Valuation Bridge 26 Equity valuation sensitivities are provided on key variables. Alternative valuation methodology We have assessed a comparable company equity valuation for the company of $5,179m-$5,844m. This is based on the current earnings multiples of listed comparable generator/retailers globally. This valuation provides a cross-check of the equity valuation based on our primary methodology, discounted cashflow. This valuation range lies below our primary valuation due, in part to the positive net present value of modelled development projects included in our primary valuation. Relative disclosure We have assessed the disclosure levels of MER’s financial reports and presentations over the last financial period against listed and non-listed companies operating in the electricity generation and energy retailing sector in New Zealand. -

Before the Board of Inquiry Statement of Evidence Of

BEFORE THE BOARD OF INQUIRY In the matter of a Board of Inquiry appointed under s146 of the Resource Management Act 1991 to consider an application by Mighty River Power Limited for resource consents to construct and operate a Windfarm at Turitea STATEMENT OF EVIDENCE OF JAMES TALBOT BAINES Dated: 22nd May 2009 Contact: Andrew Brown Address: Council Chambers The Square Palmerston North Telephone: (06) 356 8199 Facsimile: (06) 355 4155 Email: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Bio-data and experience .................................................................................... 1 1.2 Brief for this Social Impact Assessment ............................................................. 2 1.3 The proposal being assessed ............................................................................ 2 2 ASSESSMENT APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY ................................................. 3 2.1 Introduction and rationale ................................................................................... 3 2.2 Consultation coverage ....................................................................................... 4 2.3 Frameworks for assessment .............................................................................. 5 2.4 Sources of information ....................................................................................... 6 2.5 Citizens Panel Survey ....................................................................................... -

Castle Hill Wind Farm: Electricity-Related Effects Report

Castle Hill Wind Farm: Electricity-Related Effects Report Prepared for Genesis Energy July 2011 Concept Consulting Group Limited Level 6, Featherston House 119-121 Featherston St PO Box 10-045, Wellington, NZ www.concept.co.nz Contents 1 Introduction .....................................................................................................................6 1.1 Purpose..................................................................................................................................6 1.2 Information sources ..............................................................................................................6 1.3 Concept Consulting Group.....................................................................................................6 2 The Castle Hill Wind Farm Project....................................................................................7 2.1 Project Outline.......................................................................................................................7 2.2 Key Electrical Parameters for CHWF......................................................................................7 3 Electricity in the New Zealand Economy..........................................................................8 3.1 Electricity and Consumer Energy...........................................................................................8 3.2 Electricity consumption and supply in New Zealand.............................................................9 3.3 Historical Electricity Demand -

Did Impact Assessment Influence the Decision Makers? IAIA'12

Did Impact Assessment influence the decision makers? The Turitea wind farm proposal in New Zealand IAIA’12 – Porto,,g Portugal Theme Forum: Even renewables may not be acceptable: Negotiating community responses to wind energy through impact assessment The setting Wind farms near the city of Palmerston North: existing (3), permitted (1) and proposed (1) Te Apiti wind farm as seen from near the village of Ashhurst Tararua wind farm as seen from the village of Ashhurst Tararua wind farm – stage 1 – lattice towers. Sheep farming continues. Tararua wind farm (3-bladed, 2MW) and Te Rere Hau wind farm (2-bladed, 500kW) City of Palmerston North from Te Rere Hau wind farm Te Rere Hau wind farm from Palmerston North City Which communities? 1st wind farm: built by Palmerston North lines company to supply Palmerston North Now: all wind farms supply the national (grid) community Rural-residential communities closest to the windfarms? The next proposal – wider community context The next proposal – localised community context The next proposal – localised community context SIA activities: Multiple-method approach Surveys (226 & 212 respondents) •Random survey of city residents (Citizen Panel) •Spatially targeted survey of people living within 5km of an existing turbine (ex-post survey) Focus groups (41 participants) •1 for landowners with turbines; •4 for near neighbours without turbines Interviews (34) •Recreation groups, tourism sector, wind farm companies, construction/servicing companies, regional economic development interests, iwi Declining levels -

Wind Farm Update April 2008.Pdf

April 2008 W NNDDFAARMRM ByUUPDATE Dr Julian Elder PDATE he decision on WEL Networks’ proposed wind farm at Te Uku is expected to be Tannounced by the Waikato District Council in the near future. Like you, we keenly await the outcome. I’m sending you this UPDATE to provide important background information as part of WEL’s commitment to on-going consultation with the greater Raglan community. The UPDATE forms no part of the resource consent process. The business case for the wind farm is strong and financially sound. Otherwise, we would not be risking an investment of $200 million, particularly when we are owned by the community. The Te Uku wind farm project will only go ahead if it is profitable. But we do acknowledge that there are residents with mixed feelings about the wind farm, and those who oppose it. The proposed wind farm is among the smaller of the wind farms either in operation or planned elsewhere in New Zealand. The generation of power to meet the growing demands of consumers and industry always presents a dilemma. New Zealanders are demanding renewable energy resources, yet at the same time they are demanding more supply. In the Waikato region, 55 percent more power will be needed in the next 10 years to meet the growth of both residential and business consumers. NO TO NUCLEAR POWER Coal fired power stations are being rejected and no-one supports nuclear power. Other ways to deliver power, such as bio mass, tidal and solar, are not currently realistic in commercial terms. Wind, as an energy resource, continues globally as the most widely accepted form of renewable and sustainable generation. -

Kaimai Wind Farm Tourism and Recreation Impact Assessment

Kaimai Wind Farm Tourism and Recreation Impact Assessment REPORT TO VENTUS ENERGY LTD MAY 2018 Document Register Version Report date V 1 Final draft 31 August 2017 V2 GS comments 10 Oct 2017 V3 Visual assessment, cycle route 30 Nov 2017 V4 Updated visual assessment 16 February 2018 V5 Turbine update 30 May 2018 Acknowledgements This report has been prepared by TRC Tourism Ltd. Disclaimer Any representation, statement, opinion or advice, expressed or implied in this document is made in good faith but on the basis that TRC Tourism is not liable to any person for any damage or loss whatsoever which has occurred or may occur in relation to that person taking or not taking action in respect of any representation, statement or advice referred to in this document. K AIMAI WIND FARM TOURISM AND RECREATION IMPACT ASSESSMENT 2 Contents Contents ................................................................................................................. 3 1 Introduction and Background ........................................................................... 4 2 Existing Recreation and Tourism Setting ........................................................... 5 3 Assessment of Potential Effects ...................................................................... 12 4 Recommendations and Mitigation .................................................................. 18 5 Conclusion ...................................................................................................... 20 K AIMAI WIND FARM TOURISM AND RECREATION IMPACT ASSESSMENT -

Te Uku Wind Farm, Near Raglan, Are Finding Out

new zealand wind energy association ›› www.windenergy.org.nz Wind Energy Case Study Business and community opportunities There is more to wind energy than wind turbines and renewable energy. A new wind farm can become a catalyst for business and community renewal, as the people involved with Te Uku wind farm, near Raglan, are finding out. Earthworks at Te Uku wind farm Out towards Raglan, Meridian Energy is developing a new wind “I was just a one-man band but I had to employ staff and learn all farm at Te Uku. This high and windy site has become an important about how to do that. It was a real eye opener but I had lots of help community asset. The wind farm has added a new, positive dynamic from the managers of the construction firms Hick Bros and Spartan to this isolated farming site. Construction,” says Jim. It was a very wet winter, which did not help, but Jim is proud of Business opportunities his contribution. “We all need power at the end of the day.” An important aspect of the construction and ongoing management Local Hamilton firm Spartan Construction together with Hick of the wind farm was that the existing farm operations had to Bros from Silverdale formed Hick Spartan Joint Venture and continue with little or no disruption. That meant that stock and won the contract to supply infrastructure roading, foundations pasture had to be managed along with heavy construction, quarrying and erosion and sediment control at Te Uku. They won the and new roading. Jim Munns, a local fencer played an integral role. -

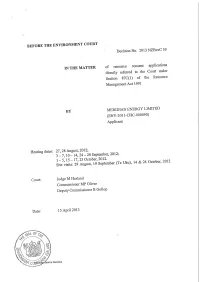

Decision No. 2013 Nzenvc 59 of Resource Consent. Applications

BEFORE THE ENVIRONMENT COURT Decision No. 2013 NZEnvC 59 of resource consent. applications IN THE MATTER directly referred to the Court under Section 8.7C(1) of the Resource Management Act 1991 MERIDIAN ENERGY LIMITED BY (ENV -2011-CHC-000090) Applicant Hearing dates: 27, 28 August, 2012; 3-7, 10- 14, 24-28 September, 2012; 1-5, 15-17, 23 October, 2012. Site visits: 29 August, 19 September (Te Uku), 14 & 24 October, 2012 Court: Judge M Harland Commissioner MP Oliver Deputy Commissioner B Gollop Date: 15 Apri12013 INTERIM DECISION A. The applications for resource consent are granted subject to amended conditions. B. We record for the ·avoidance of doubt, that this decision is final in respect of the confirmation of the grant of the resource consents (on amended conditions) but is interim in respect of the precise wording of the conditions, and in particular the details relating to the Community Fund condition(s). C. We direct the Hurunui District Council and the Canterbury Regional Council to submit to the Court amended conditions of consent giving effect to this decision by 17 May 2013. In preparing the amended conditions the Councils are to consult with the other parties, particularly in relation to the condition(s) relating to the Community Fund. D. If any party wishes to make submissions in relation to the Community Fund conditions, these are to be filed by 17 May 2013. E. Costs are reserved. Hurunui District Council Respondent Canterbury Regional Council Respondent Appearances: Mr A Beatson, Ms N Garvan and Ms E Taffs for Meridian -

Section 87F Report to Waka Kotahi Nz Transport Agency

IN THE MATTER of the Resource Management Act 1991 AND IN THE MATTER of applications by Waka Kotahi NZ Transport Agency to Manawatu Whanganui Regional Council for resource consents associated with the construction and operation of Te Ahu a Turanga: Manawatū Tararua Highway. SECTION 87F REPORT TO WAKA KOTAHI NZ TRANSPORT AGENCY MANAWATŪ-WHANGANUI REGIONAL COUNCIL 25 May 2020 Section 87F Report APP-2017201552.00 - Te Ahu a Turanga: Manawatū Tararua Highway 1 Prepared by Mark St.Clair – Planning A. OUTLINE OF REPORT 1 This report, required by section 87F of the Resource Management Act 1991 (“RMA”), addresses the issues set out in sections 104 to 112 of the RMA, to the extent that they are relevant to the applications lodged with the Manawatū-Whanganui Regional Council (“Horizons”) The consents applied for, by Waka Kotahi NZ Transport Agency (the “Transport Agency”) are required to authorise the construction, operation and maintenance of the Te Ahu a Turanga: Manawatū Tararua Highway (the “Project”). 2 In addition, the Transport Agency separately applied for a Notice of Requirement (“NoR”) to Palmerston North City Council (“PNCC”), Tararua District Council (“TDC”) and Manawatu District Council (“MDC”). The Environment Court confirmed the designation for the Project, including a more northern alignment (discussed later in this section 87F report), subject to conditions, on 23 March 2020. While this section 87F report only addresses the applications lodged with MWRC, the designation and the associated conditions have also been considered as part of the assessment. 3 This report has been prepared in accordance with section 87F of the RMA which sets out the matters the report must cover.