Before the Board of Inquiry Statement of Evidence Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complaint to the New Zealand Law Society

Complaint to the New Zealand Law Society This complaint concerns Karen Price of Chancery Green lead counsel to Mighty River Power for the Turitea wind farm. This complaint is made on behalf of all adversely affected parties The principle issues and findings of fact are classified into 15 categories labeled A - O. Links to supporting documents are numbered 1- 67. The linked documents are evidence to be considered in their entirety and frequently cover one or more of the 15 categories A - O. Note that in several instances for clarity there are duplicate links. 17 Specific questions are addressed to the New Zealand Law Society. A. Kenderdine not a judge with a warrant Ms Price knew that for the last 13 months during the Turitea Call-In, from August 6 2010, that Shonagh Kenderdine was not a judge with a warrant. She not only failed to communicate this to submitters but was actively involved as the key player in suppressing this material fact by continuing her very prominent participation in the charade. Both Price and Kenderdine were well known to each other. “Highlights for me were Judge Shonagh Kenderdine on how climate change is being treated in the Environment Court (with special reference to sea level rise), Karen Price on the process (and contractual pitfalls) of carbon trading………” 1/ http://hot-topic.co.nz/the-green-green-grass-of-home/ This astounding statement from Chancery Green’s website shows not only what a “cultivated” little club Price belongs to, but who she “cultivates” and that includes judges. “The key to anticipating problems is holding excellent knowledge about the decision-maker. -

Download Meeting Summary

Turitea wind farm Community Liaison Group 10 February 2021 MARGARET KOUVELIS welcomed everyone to the meeting, noting it was being held at a new time (5pm) and the intention to hold meeting to one hour. She noted that everyone should have signed in using the Golf Club’s QR poster downstairs, and handed over to Dennis Radich. Present from Mercury: Dennis Radich (Project Director), John Campbell (Project Manager), Duncan Annandale (Property Manager), Mark Henry (Environmental Resources Manager), Katy Scoullar (Communications Manager). From Vestas: Kenn Wood (Project Manager) HOW CAN WE IMPROVE THESE MEETINGS? We’ve been looking at what these meetings are for, and whether we achieve that • Length of meetings • What we use the time to talk about • Room hire and catering 2 MEETING FORMAT RE-SET DENNIS said that it is now a logical time to review this meeting format as in May it will be 2 years since our first meeting, and major construction work on the transmission line is largely complete. We wanted to know how we could improve the way we hold these meetings to make them more useful and valuable. Attendance from people in the community has dwindled. Take away the project and contrator teams and there’s actually a very small number who attend. We used our email mailing list to seek feedback on the meeting format, along with the other ways we share information with the community. Our conclusions are that these meetings are too long, we hire a room too big for what we need and because the meetings are so long we need sustenance. -

Historic Places in Palmerston North

Historic Places In Palmerston North An inventory of places listed on the Register of the New Zealand Historic Places Trust Pouhere Taonga Historic Places Manawatu-Horowhenua Incorporated 2013 Historic Places in Palmerston North A project of Historic Places Manawatu-Horowhenua Inc. ISSN: 2357-1861 Prepared by: Rosemary Harris Margaret Tate Pat Scrivens First published in Palmerston North 2007; revised 2013. Design: Ess’Dee Associates Ltd. Copyright: Historic Places Manawatu-Horowhenua Inc. You are free to copy this material for non-commercial use. For all other purposes permission is required from Historic Places Manawatu-Horowhenua Inc., PO Box 732, Palmerston North. Historic Places Manawatu-Horowhenua Inc. revised 2013 1 Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................3 Palmerston North Central Business District Regent Theatre .......................................................................................................................................................5 All Saints' Church (Anglican) ...................................................................................................................................7 Cathedral of the Holy Spirit (Catholic) ....................................................................................................................9 Grand Hotel Building (Former)..............................................................................................................................11 -

Primary Teams

Primary Teams – Divisions and Structure Year 3-4 Year 3-4 Year 3-4 Year 5-6 Year 5-6 Year 5-6 Year 5-6 Year 5-6 Division 1 Division 2 Division 3 Division 1 Division 2 Division 3 Division 4 Division 5 Aokautere Cloverlea Hokowhitu Aokautere Parkland Cloverlea NSS Hokowhitu Wildcats Jets Magic Thunder Pistons Giants Kakariki Shooters Whakarongo Whakarongo Winchester Central Normal CSNS Ashhurst Riverdale Carncot Celtics Knicks 3-4 Magic Clippers Raptors Bulls Gold Wairau Takaro RSS Milson Mana Mt Whakarongo Coverlea Warriors Diamonds Suns Vipers Tamariki 5-6 Biggs Lakers Rams RSS Central Normal Linton Wiarau Whakarongo Terrace End Milson Cornerstone Heat Thunder Bulls Wairua Rockets School Titans Rockets Red CSNS Ashhurst Riverdale RSS Turitea Takaro Cornerstone Central Normal Rockets Cavaliers Breakers Lakers Warriors Mana Green Jazz CSNS Parkland Cloverlea CSNS Roslyn Cornerstone St James Winchester Lakers Pelicans Sharks Timberwolves Bullets Blue Hoops 5-6 Central Normal Mana Tamariki CSNS TKKMOM CSNS Riverdale Takaro PNACS Bulls Y3-4 The Cavs Whai Knicks All Stars Kea Bullets OLOL KN Carncot Carncot Wairau Linton OLOL CSNS Thunder Dannevirke Y3-4 Blue Mon Stars Celtics Storm Magic Milson Ashhurst PNACS Ashhurst NSS Whakarongo Hokowhitu West End School Jetts Cavaliers Tigers All Stars Kahurangi Raptors Steelers Ballers Riverdale CSNS Pistons The Bulls Total 9 Teams Total 8 Teams Total 9 Teams Total 9 Teams Total 9 Teams Total 9 Teams Total 10 Teams Total 10 Teams Competition Structure Y3-4 Year 5-6 Grading Games 2 Weeks Grading Games 2 Weeks Round Robin 8 Weeks Round Robin 8 Weeks Semis and Finals 2 Weeks Semis and Finals 2 Weeks NB: Each Grade except Y5-6 Division 5 will have a BYE. -

3. Palmerston North's Housing Market

1 Contents 1. Overview .................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Annual trends .......................................................................................................................... 3 3. Palmerston North’s housing market ...................................................................................... 4 New residential building consents ........................................................................................... 4 Census housing data ................................................................................................................ 8 Other housing market indicators ........................................................................................... 10 4. Business Activity .................................................................................................................... 14 Non-residential building consents ......................................................................................... 14 5. Outlook for major construction projects in Palmerston North and the wider region ....... 16 6. Retail trends .......................................................................................................................... 16 7. Gross domestic product (GDP) .............................................................................................. 18 8. Employment trends .............................................................................................................. -

River Classification of the Manawatu-Wanganui Region to Support the Definition of the Life-Supporting Capacity Value: Technical Report to Support Policy Development

MANAGING OUR ENVIRONMENT GETTING PEOPLE PLACES Ri ver Classification of the Manawatu-Wanganui Region to Support the Definition of the Life-Supporting Ca pacity Value: Te chnical Report to Support Policy Development River Classification of the Manawatu-Wanganui Region to Support the Definition of the Life-Supporting Capacity Value: Technical Report to Support Policy Development May 2007 Authors Dr Olivier Ausseil Senior Scientist – Water Quality Maree Clark Research Associate Reviewed By Dr John Quinn Principal Scientist National Institute of Water and Atmosphere (NIWA) Dr Russell Death Senior Lecturer Institute of Natural Resources Massey University May 2007 ISBN: 1-877413-79-8 Report No: 2007/EXT/791 CONTACT 24hr Freephone 0508 800 800 [email protected] www.horizons.govt.nz Kairanga Cnr Rongotea & Kairanga-Bunnythorpe Rds Palmerston North Levin Palmerston North 11 Bruce Road 11-15 Victoria Avenue SERVICE Marton REGIONAL Cnr Hammond & Hair Sts DEPOTS CENTRES HOUSES Taihape Wanganui Torere Road Taumarunui 181 Guyton Street Ohotu 34 Maata Street Woodville Cnr Vogel (SH2) & Tay Sts POSTAL Horizons Regional Council, Private Bag 11025, Manawatu Mail Centre, Palmerston North 4442 | F 06 9522 929 ADDRESS GETTING PEOPLE PLACES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report is part of a suite of technical reports to support the development of the water and catchment management regime proposed by Horizon’s new Regional Plan, the One Plan. A key goal for this regime will be to ensure the values our regional community places on our rivers and lakes are maintained or improved. Twenty three waterbody values, applying to all or parts of the Region’s rivers and lakes, have been identified in a separate report (Ausseil and Clark, 2007). -

Hearing Decision 20100204 FINAL

IN THE MATTER OF The Resource Management Act 1991 AND Application for resource consent made pursuant to Section 88 of the Act – TO Manawatu-Wanganui Regional Council (MWRC) Application Numbers: 104949, 104950, 104951, 104952 AND Tararua District Council (TDC) File Number: 12003.030 BY New Zealand Windfarms Limited IN RELATION TO To the development of an extension to the Te Rere Hau wind farm on the eastern side of the Tararua Ranges. The proposed Te Rere Hau Eastern Extension consists of 56 wind turbines located across approximately 300 hectares. Each turbine tower is 29 metres in height and reaches a maximum height of 47 metres with the tower and blade combined. Access to the proposed site will be off the Pahiatua Track via North Range Road. Decision of Joint Hearings Commissioners HEARING DATES: 6 – 14 October; 28-29 October; 11 November 2009 HEARING PANEL: David McMahon (Independent Commissioner and Chair) Cr Annette Main (MWRC Councillor) Cr Warren Davidson (TDC Councillor) DATE OF DECISION: 31 January 2010 Notice of Decision 1 1. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................5 2. THE PROPOSAL...........................................................................................................5 3. SITE LOCALITY AND DESCRIPTION.....................................................................6 Application Site..............................................................................................................................................6 Surrounding -

Urban Design Strategy

Urban Design Strategy DMS #377477 September 2010 Executive Summary This strategy provides the foundation for a positive and proactive approach to urban design in Palmerston North. The Urban Design Strategy presents a vision for the physical development of Palmerston North that will contribute to the City being recognised as vibrant, caring, creative, and sustainable. Everyone will be encouraged to contribute to achieving the outcomes of this strategy. This includes the local iwi Rangitaane, large organisations, Council officers, professionals in the development industry, private investors, and the community groups who all have a part to play in changing the City’s urban environment. The Council has identified the drivers for long term positive change in the urban environment of the City. These are the public realm, diversity, connectivity, character, and the environment. The drivers were identified through consultation with stakeholders in the development industry, education and cultural sectors, and discussions with Rangitaane. The Strategy states the outcomes from a holistic approach to urban design and includes initiatives which will be a catalyst for improved design in the City. Summary of Urban Design Drivers Driver Sub-drivers Public Realm Making places people-friendly and inviting Ensuring coherency in design Actively managing and maintaining the City’s public spaces Developing the Manawatu River as a destination Welcoming and memorable entrances to the City Creating a vibrant City centre Diversity Promoting a mix of uses Vibrancy -

F.D.L Building (Former Glaxo Laboratories Building) Campbell Road, Bunnythorpe

F.D.L Building (Former Glaxo Laboratories Building) Campbell Road, Bunnythorpe NZHPT Registration Number: 1186 NZHPT Registration Type: Historic Place – Category II NZHPT Registration Date: 2/07/82 City/District Council: Palmerston North City Council District Plan Status: To be confirmed following recent boundary change Photograph by William Stadtwald Demchick (Own work) [CC-BY-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons. Brief History Glaxo Laboratories (NZ) Limited manufactured Glaxo milk powder and other products at this factory in Bunnythorpe. The forerunner of the Glaxo business, successful Wellington merchant business Joseph Nathan & Company, was established in 1873 by Joseph Nathan. Nathan was a prominent member of the Wellington Jewish community, held a number of directorships and became President of the Chamber of Commerce. His son Frederick Nathan was Mayor of Palmerston North from 1923 to 1927, and was instrumental in ensuring that the Turitea site was chosen for the proposed agricultural college (now Massey University). Joseph Nathan & Company began milk powder production part of a butter factory at Makino in 1904. John Merrett, an English engineer with expertise in milk powder operations, was employed to oversee the establishment of production. After just a few months, it was decided that the factory was unsuitable for large-scale milk powder production, and a purpose-built factory was constructed at Bunnythorpe. Historic Places Manawatu-Horowhenua Inc. revised 2013 76 John Merrett drew up the plans for the timber and corrugated iron building and supervised its construction. He stayed on as Manager of the Bunnythorpe factory through its first year of production. -

3.45Pm 4.15Pm 4.45Pm 5.15Pm

Primary Draw Thursday 24 June 2021 Week 7 Court 1 Court 2 Court 3 Court 4 Court 5 Court 6 Court 7 Court 8 Court 9 CSNS Central Cloverlea Carncot Wairau Hokowhitu Carncot Cloverlea Hokowhitu Lakers Normal Bulls Jets Gold Mon Stars Shooters Blue Rams Steelers V V V V V V V V V CSNS RSS Whakarongo Central CSNS CSNS RSS Cornerstone Cornerstone 3.45pm Rockets Heat Knicks Normal Jazz Knicks Magic Lakers Red Green Milson Mana Carncot Ashhurst TKKMOM Turitea Ashhurst OLOL Cloverlea Jetts Tamariki Y3-4 Y3/4 All Stars Whai Warriors Raptors Storm Giants V V V V V V V V V Whakarongo Central RSS Milson CSNS Whakarongo Riverdale Riverdale Riverdale 4.15pm Celtics Normal Suns Vipers Clippers Rockets All Stars Bulls Pistons Thunder FRIENDLY OLOL Ashhurst CSNS CSNS NSS NSS St James WES CSNS Thunder Cavaliers The Cavs Timberwolves Kahurangi Kakariki Hoops Ballers The Bulls V V V V V V V V V Wairau Aokautere Linton Mana Roslyn Linton Milson Winchester PNACS 4.45pm Warriors Wildcats Bulls Tamariki Y5-6 Bullets Celtics Rockets Y5-6 Bullets FRIENDLY FRIENDLY Deferred Games from last week – playing in FLY Ashhurst Cloverlea PNACS Wairau Mt Terrace End PALMY Arena on the JETS court! Raptors Sharks Tigers Wairua Biggs Titans 3.45pm WES Ballers v PNACS Bullets V V V V V V 4.15pm Mt Biggs v Terrace End Titans Aokautere Riverdale Winchester Central Cornerstone Whakarongo 4.45pm Hokowhitu Shooters v Central Normal Jazz 5.15pm Thunder Breakers Y3-4 Normal Magic Blue Lakers 5.15pm Whakarongo Raptors v Riverdale All Stars 5.30pm NSS Kakariki v Cornerstone Blue Please check DRAW for your SECOND GAME! BYE TEAMS: Parkland Pelicans / Hokowhitu Magic / Parkland Pistons / Whakarongo Raptors – Takaro AWAY this week due to School commitments REMINDER: ONE PERSON from each team to scorebench your OWN GAMES please. -

Lower Manawatu Scheme & Ashhurst Stream Scheme

LOWER MANAWATU SCHEME & ASHHURST STREAM SCHEME Responsibilities for the maintenance of channel management, flood control and river bank amenity assets within Palmerston North City December 2013 Author Derek McKee Projects Engineer Editor Allan Cook Group Manager Operations December 2013 REPORT NO: 2013/EXT/1348 ISBN No. 978-1-927250-51-8 For more information contact CONTACT 24hr Freephone 0508 800 800 [email protected] www.horizons.govt.nz Kairanga Cnr Rongotea & Kairanga-Bunnythorpe Rds Palmerston North Levin Palmerston North 11 Bruce Road 11-15 Victoria Avenue SERVICE Marton REGIONAL Cnr Hammond & Hair Sts DEPOTS CENTRES HOUSES Taihape Wanganui Torere Road Taumarunui 181 Guyton Street 34 Maata Street Ohotu Woodville Cnr Vogel (SH2) & Tay Sts POSTAL Horizons Regional Council, Private Bag 11025, Manawatu Mail Centre, Palmerston North 4442 | F 06 9522 929 ADDRESS Responsibilities for the maintenance of channel management, flood control and river bank amenity assets within Palmerston North City CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Document Scope 3. Manawatu River 3.1 Background 3.2 Riverbank Erosion Protection 3.3 Stopbanks and other Flood Protection Structures 3.4 Secondary Stopbank from the Ruahine Street Carpark to the City Boundary at Napier Road Drain 3.5 Floodgated Stormwater Outlets 3.6 Riverside Pathways 3.7 Amenity Enhancements 4. Mangaone Stream 4.1 Mangaone Stream Channel Banks 4.2 Stopbanks 4.3 Floodgated Stormwater Outlets 4.4 Pathways 5. Kawau Stream 6. Little Kawau Stream 7. Kawau Diversion 8. Jacks Creek 9. Derby Creek 10. Pioneer Highway Drain 11. Napier Road Drain (Kelvin Grove Outfall Channel) 12. Stoney Creek 13. Raukawa Road Drain Responsibilities for the maintenance of channel management, flood control and river bank amenity assets within Palmerston North City i October 2013 Contents 14. -

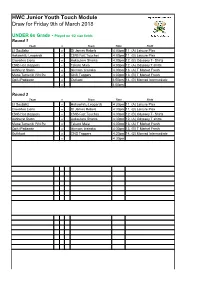

HWC Junior Youth Touch Module Draw for Friday 9Th of March 2018

HWC Junior Youth Touch Module Draw for Friday 9th of March 2018 UNDER 6s Grade - Played on 1/2 size fields Round 1 Team v Team Time Field Lil Souljahz v St James Rebels 4:00pm 11. (A) Leisure Plex Hokowhitu Leopards v CSNS Fast Touches 4:00pm 11. (B) Leisure Plex Cloverlea Lions v Aokautere Sharks 4:00pm 12. (B) Odyssey T- Shirts CSNS Hot steppers v Takaro Maia 4:00pm 12. (A) Odyssey T shirts Ashhurst Storm v tkkmom tirairaka 4:00pm 13. (A) T Market Fresh Mana Tamariki Pihi Pu v CNS Taggers 4:00pm 13. (B) T Market Fresh Opiki Padawan v Outkast 4:00pm 14. (B) Monrad Intermediate v 4:00pm Round 2 Team v Team Time Field Lil Souljahz v Hokowhitu Leopards 4:30pm 11. (A) Leisure Plex Cloverlea Lions v St James Rebels 4:30pm 11. (B) Leisure Plex CSNS Hot steppers v CSNS Fast Touches 4:30pm 12. (B) Odyssey T- Shirts Ashhurst Storm v Aokautere Sharks 4:30pm 12. (A) Odyssey T shirts Mana Tamariki Pihi Pu v Takaro Maia 4:30pm 13. (A) T Market Fresh Opiki Padawan v tkkmom tirairaka 4:30pm 13. (B) T Market Fresh Outkkast v CNS Taggers 4:30pm 14. (B) Monrad Intermediate v 4.30pm HWC Junior Youth Touch Module Draw for Friday 9th of March 2018 UNDER 8s's A/B Grade - Played on 1/2 size fields Round 1 Team v Team Time Field Lil Souljahz v Turitea Hurricanes 5.00pm 1. (A) Lido CSNS Gold v Somerset Soldiers 5.00pm 1.