Sloan Et Al. 2018-Papua Development.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Jungles of Sumatra and the Beaches of Bali to the Surf Breaks of Lombok, Sumba and Sumbawa, Discover the Best of Indonesia

INDONESIAThe Insiders' Guide From the jungles of Sumatra and the beaches of Bali to the surf breaks of Lombok, Sumba and Sumbawa, discover the best of Indonesia. Welcome! Whether you’re searching for secluded surf breaks, mountainous terrain and rainforest hikes, or looking for a cultural surprise, you’ve come to the right place. Indonesia has more than 18,000 islands to discover, more than 250 religions (only six of which are recognised), thousands of adventure activities, as well as fantastic food. Skip the luxury, packaged tours and make your own way around Indonesia with our Insider’s tips. & Overview Contents MALAYSIA KALIMANTAN SULAWESI Kalimantan Sumatra & SUMATRA WEST PAPUA Jakarta Komodo JAVA Bali Lombok Flores EAST TIMOR West Papua West Contents Overview 2 West Papua 23 10 Unique Experiences A Nomad's Story 27 in Indonesia 3 Central Indonesia Where to Stay 5 Java and Central Indonesia 31 Getting Around 7 Java 32 & Java Indonesian Food 9 Bali 34 Cultural Etiquette 1 1 Nusa & Gili Islands 36 Sustainable Travel 13 Lombok 38 Safety and Scams 15 Sulawesi 40 Visa and Vaccinations 17 Flores and Komodo 42 Insurance Tips Sumatra and Kalimantan 18 Essential Insurance Tips 44 Sumatra 19 Our Contributors & Other Guides 47 Kalimantan 21 Need an Insurance Quote? 48 Cover image: Stocksy/Marko Milovanović Stocksy/Marko image: Cover 2 Take a jungle trek in 10 Unique Experiences Gunung Leuser National in Indonesia Park, Sumatra Go to page 20 iStock/rosieyoung27 iStock/South_agency & Overview Contents Kalimantan Sumatra & Hike to the top of Mt. -

Report on Biodiversity and Tropical Forests in Indonesia

Report on Biodiversity and Tropical Forests in Indonesia Submitted in accordance with Foreign Assistance Act Sections 118/119 February 20, 2004 Prepared for USAID/Indonesia Jl. Medan Merdeka Selatan No. 3-5 Jakarta 10110 Indonesia Prepared by Steve Rhee, M.E.Sc. Darrell Kitchener, Ph.D. Tim Brown, Ph.D. Reed Merrill, M.Sc. Russ Dilts, Ph.D. Stacey Tighe, Ph.D. Table of Contents Table of Contents............................................................................................................................. i List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. v List of Figures............................................................................................................................... vii Acronyms....................................................................................................................................... ix Executive Summary.................................................................................................................... xvii 1. Introduction............................................................................................................................1- 1 2. Legislative and Institutional Structure Affecting Biological Resources...............................2 - 1 2.1 Government of Indonesia................................................................................................2 - 2 2.1.1 Legislative Basis for Protection and Management of Biodiversity and -

A Radiographic Study of Human-Primate Commensalism

Developments in Primatology: Progress and Prospects Series Editor Russell H. Tuttle Department of Anthropology The University of Chicago For further volumes, go to http://www.springer.com/series/5852 Sharon Gursky-Doyen ● Jatna Supriatna Editors Indonesian Primates Editors Sharon Gursky-Doyen Jatna Supriatna Department of Anthropology Conservation International Indonesia Texas A&M University University of Indonesia College Station, TX Jakarta USA Indonesia [email protected] [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-1559-7 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-1560-3 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-1560-3 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London Library of Congress Control Number: 2009942275 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) S.L. Gursky-Doyen dedicates this volume to her parents, Ronnie Bender and Burt Gursky, who after all these years still do not really know what she does, but they proudly display her books on their coffee table; and to her husband Jimmie who taught her what love is. -

Indonesia-11-Contents.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Indonesia Sumatra Kalimantan p490 p586 Sulawesi Maluku p636 p407 Papua p450 Java p48 Nusa Tenggara p302 Bali p197 THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Loren Bell, Stuart Butler, Trent Holden, Anna Kaminski, Hugh McNaughtan, Adam Skolnick, Iain Stewart, Ryan Ver Berkmoes PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Indonesia . 6 JAVA . 48 Imogiri . 127 Indonesia Map . 8 Jakarta . 52 Gunung Merapi . 127 Solo (Surakarta) . 133 Indonesia’s Top 20 . 10 Thousand Islands . 73 West Java . 74 Gunung Lawu . 141 Need to Know . 20 Banten . 74 Semarang . 144 What’s New . 22 Gunung Krakatau . 77 Karimunjawa Islands . 154 If You Like… . 23 Bogor . 79 East Java . 158 Cimaja . 83 Surabaya . 158 Month by Month . 26 Cibodas . 85 Pulau Madura . 166 Itineraries . 28 Cianjur . 86 Sumenep . 168 Outdoor Adventures . 32 Bandung . 87 Malang . 169 Probolinggo . 182 Travel with Children . 43 Pangandaran . 96 Central Java . 102 Ijen Plateau . 188 Regions at a Glance . 45 Borobudur . 106 Meru Betiri National Park . 191 Yogyakarta . 111 PETE SEAWARD/GETTY IMAGES © IMAGES SEAWARD/GETTY PETE Contents BALI . 197 Candidasa . 276 MALUKU . 407 South Bali . 206 Central Mountains . 283 North Maluku . 409 Kuta & Legian . 206 Gunung Batur . 284 Pulau Ternate . 410 Seminyak & Danau Bratan . 287 Pulau Tidore . 417 Kerobokan . 216 North Bali . 290 Pulau Halmahera . 418 Canggu & Around . .. 225 Lovina . .. 292 Pulau Ambon . .. 423 Bukit Peninsula . .229 Pemuteran . .. 295 Kota Ambon . 424 Sanur . 234 Gilimanuk . 298 Lease Islands . 431 Denpasar . 238 West Bali . 298 Pulau Saparua . 431 Nusa Lembongan & Pura Tanah Lot . 298 Pulau Molana . 433 Islands . 242 Jembrana Coast . 301 Pulau Seram . -

Predicting Hotspots and Prioritizing Protected Areas for Endangered Primate Species in Indonesia Under Changing Climate

biology Article Predicting Hotspots and Prioritizing Protected Areas for Endangered Primate Species in Indonesia under Changing Climate Aryo Adhi Condro 1 , Lilik Budi Prasetyo 2,* , Siti Badriyah Rushayati 2, I Putu Santikayasa 3 and Entang Iskandar 4 1 Tropical Biodiversity Conservation Program, Department of Forest Resources Conservation and Ecotourism, Faculty of Forestry, Kampus IPB Darmaga, IPB University (Bogor Agricultural University), Bogor 16680, Indonesia; [email protected] 2 Department of Forest Resources Conservation and Ecotourism, Faculty of Forestry, Kampus IPB Darmaga, IPB University (Bogor Agricultural University), Bogor 16680, Indonesia; [email protected] 3 Department of Geophysics and Meteorology, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Kampus IPB Darmaga, IPB University (Bogor Agricultural University), Bogor 16680, Indonesia; [email protected] 4 Primate Research Center, IPB University (Bogor Agricultural University), Jalan Lodaya II No 5, Bogor 16680, Indonesia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +62-812-1335-130 Simple Summary: Primates play an essential role in human life and its ecosystem. However, Indonesian primates have suffered many threats due to climate change and altered landscapes that lead to extinction. Therefore, primate conservation planning and strategies are important in maintaining their population. We quantified how extensively the protected areas overlapped primate Citation: Condro, A.A.; Prasetyo, hotspots and how it changes under mitigation and worst-case scenarios of climate change. Finally, L.B.; Rushayati, S.B.; Santikayasa, IP.; we provide protected areas recommendations based on species richness and land-use changes under Iskandar, E. Predicting Hotspots and the worst-case scenario for Indonesian primate conservation planning and management options. -

Bugis Settlers in East Kalimantan's Kutai National Park

Front pages 6/7/98 8:17 PM Page 1 BUGIS SETTLERS IN EAST KALIMANTANÕS KUTAI NATIONAL PARK THEIR PAST AND PRESENT AND SOME POSSIBILITIES FOR THEIR FUTURE Andrew P. Vayda and Ahmad Sahur CIFOR CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL FORESTRY RESEARCH CIFOR Special Publication Front pages 6/7/98 8:17 PM Page 2 © 1996 Center for International Forestry Research Published by Center for International Forestry Research mailing address: P.O. Box 6596 JKPWB, Jakarta 10065, Indonesia tel.: +62-251-622622 fax: +62-251-622100 e-mail: [email protected] WWW: http://www.cgiar.org/cifor with support from UNDP/UNESCO/Government of Indonesia Project INS/93/004 on Management Support to Kutai National Park Jl. M.H. Thamrin 14 Jakarta Pusat, Indonesia ISBN 979-8764-12-9 Front pages 6/7/98 8:17 PM Page 3 CONTENTS Preface v Introduction 1 Some Teluk Pandan Findings Amenability to Relocation 7 The Pull of Industry and the Pull of the Forest 8 Compensation for Land 11 Patrons and Clients 15 Willingness to Move in Return only for Compensation 18 Effects of Compensation Expectations on Buying and Using Land 24 Comparisons Selimpus 27 Sangkimah 33 Bugis Settlers Relocated to Km 24 40 Bugis Settlers Relocated from Bukit Soeharto 43 Concluding Remarks 49 References Cited 52 Front pages 6/7/98 8:17 PM Page 5 PREFACE This report presents detailed results of human ecology-anthropological research in a very specific place, with a specific ethnic group, and deals with a context which a particular national government sees as a specific ÒproblemÓ. This would seem to make it an unlikely candi- date for publication by CIFOR, an institution mandated and dedicated to research which is of widespread public benefit. -

Our Readers Author Thanks Send Us Your Feedback

328 SEND US YOUR FEEDBACK We love to hear from travellers – your comments keep us on our toes and help make our books better. Our well-travelled team reads every word on what you loved or loathed about this book. Although we cannot reply individually to postal submissions, we always guarantee that your feedback goes straight to the appropriate authors, in time for the next edition. Each person who sends us information is thanked in the next edition – the most useful submissions are rewarded with a selection of digital PDF chapters. Visit lonelyplanet.com/contact to submit your updates and suggestions or to ask for help. Our award-winning website also features inspirational travel stories, news and discussions. Note: We may edit, reproduce and incorporate your comments in Lonely Planet products such as guidebooks, websites and digital products, so let us know if you don’t want your comments reproduced or your name acknowledged. For a copy of our privacy policy visit lonelyplanet.com/privacy. Helen van Lindere, Jeremy Clark, Peter Hogge OUR READERS and my guides Bian Rumai, Esther Abu, Many thanks to the travellers who used Jeffry Simun, Susan Pulut and Syria Lejau the last edition and wrote to us with help- (Gunung Mulu National Park); Apoi Ngimat, ful hints, useful advice and interesting Jaman Riboh, Joanna Joy, Rebita Lupong, anecdotes: Antonio Almeida, Alexandra Bardswell, Tamara Rian John Pasan Lamulun, Stephen and Tine, Bedeaux, Neesha Copley, Augusto Garolla, and Stu Roach (Bario); Mr Lim (Chong Teah), Paul Gurn, Lloyd Jones, Laurel -

Histories of Protected Areas: Internationalisation of Conservationist Values and Their Adoption in the Netherlands Indies (Indonesia)

Histories of Protected Areas: Internationalisation of Conservationist Values and their Adoption in the Netherlands Indies (Indonesia) PAUL JEPSON* AND ROBERT J. WHITTAKER School of Geography and the Environment University of Oxford Mansfield Road, Oxford, OX1 3TB, UK *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT National parks and wildlife sanctuaries are under threat both physically and as a social ideal in Indonesia following the collapse of the Suharto New Order regime (1967–1998). Opinion-makers perceive parks as representing elite special interest, constraining economic development and/or indigenous rights. We asked what was the original intention and who were the players behind the Netherlands Indies colonial government policy of establishing nature ‘monu- ments’ and wildlife sanctuaries. Based on a review of international conservation literature, three inter-related themes are explored: a) the emergence in the 1860– 1910 period of new worldviews on the human-nature relationship in western culture; b) the emergence of new conservation values and the translation of these into public policy goals, namely designation of protected areas and enforcement of wildlife legislation, by international lobbying networks of prominent men; and 3) the adoption of these policies by the Netherlands Indies government. This paper provides evidence that the root motivations of protected area policy are noble, namely: 1) a desire to preserve sites with special meaning for intellectual and aesthetic contemplation of nature; and 2) acceptance that the human conquest of nature carries with it a moral responsibility to ensure the survival of threatened life forms. Although these perspectives derive from elite society of the American East Coast and Western Europe at the end of the nineteenth century, they are international values to which civilised nations and societies aspire. -

Managing Protected Areas in the Tropics

\a Managing Protected . Areas in the Tropics i National Parks, Conservation, and Development The Role of Protected Areas in Sustaining Society Edited by JEFFREYA. MCNEELEYand KENTONR. MILLER Marine and Coastal Protected Areas A Guide for Planners and Managers By RODNEYV. SALM Assisted by JOHN R. CLARK Managing Protected Areas in the Tropics Compiled by JOHNand KATHYMACKINNON, Environmental Conservationists, based in UK; GRAHAMCHILD, former Director of National Parks and Wildlife Management, Zimbabwe; and JIM THORSELL,Executive Officer, Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas, IUCN, Switzerland Based on the Workshops on Managing Protected Areas in the Tropics World Congress on National Parks, Bali, Indonesia, October I982 Organised by the IUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas INTERNATIONALUNION FORCONSERVA~ON OF NATUREAND NATURALRESOURCES and the UNITEDNATIONS ENVIRONMENT PROGRAMME INTERNATIONALUNION FORCONSERVATION OF NATUREAND NATURALRESOURCES, GLAND, SWKZERLAND 1986 - J IUCN - THE WORLD CONSERVATION UNION Founded in 1948, IUCN - the World Conservation Union - is a membership organisation comprising governments, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), research institutions, and conservation agencies in 120 countries. The Union’s objective is to promote and encourage the protection and sustainable utilisation of living resources. Several thousand scientists and experts from all continents form part of a network supporting the work of its six Commissions: threatened species, protected areas, ecology, sustainable development, environmental law, and environmental education and training. Its thematic programmes include tropical forests, wetlands, marine ecosystems, plants, the Sahel, Antarctica, population and sustainable development, and women in conservation. These activities enable IUCN and its members to develop sound policies and programmes for the conservation of biological diversity and sustainable development of natural resources. -

Traffic Southeast Asia Report

HANGING IN THE BALANCE: AN ASSESSMENT OF TRADE IN ORANG-UTANS AND GIBBONS ON KALIMANTAN,INDONESIA VINCENT NIJMAN A TRAFFIC SOUTHEAST ASIA REPORT TRAFFIC SOUTHEAST ASIA Published by TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia © 2005 TRAFFIC Southeast Asia All rights reserved. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be produced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit TRAFFIC Southeast Asia as the copyright owner. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC Network, WWF or IUCN. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF, TRAFFIC is a joint programme of WWF and IUCN. Layout by Noorainie Awang Anak, TRAFFIC Southeast Asia Suggested citation: Vincent Nijman (2005), Hanging in the Balance: An Assessment of trade in Orang-utans and Gibbons in Kalimantan, Indonesia TRAFFIC Southeast Asia ISBN 983-3393-03-9 Photograph credit: Pet Müller’s Gibbon Hylobates muelleri, West Kalimantan, Indonesia (Ian M. Hilman/Yayasan Titian) Hanging in the Balance: An Assessment of Trade in Orang-utans and Gibbons in Kalimantan, Indonesia HANGING IN THE BALANCE: An assessment of trade in orang-utans and gibbons in Kalimantan, Indonesia Vincent Nijman August 2005 Yuyun Kurniawan/Yayasan Titian Kurniawan/Yayasan Yuyun Credit: Credit: Orang-utan and macaque skulls used for decoration in Central Kalimantan. -

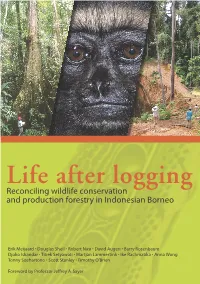

Life After Logging: Reconciling Wildlife Conservation and Production Forestry in Indonesian Borneo

Life after logging Reconciling wildlife conservation and production forestry in Indonesian Borneo Erik Meijaard • Douglas Sheil • Robert Nasi • David Augeri • Barry Rosenbaum Djoko Iskandar • Titiek Setyawati • Martjan Lammertink • Ike Rachmatika • Anna Wong Tonny Soehartono • Scott Stanley • Timothy O’Brien Foreword by Professor Jeffrey A. Sayer Life after logging: Reconciling wildlife conservation and production forestry in Indonesian Borneo Life after logging: Reconciling wildlife conservation and production forestry in Indonesian Borneo Erik Meijaard Douglas Sheil Robert Nasi David Augeri Barry Rosenbaum Djoko Iskandar Titiek Setyawati Martjan Lammertink Ike Rachmatika Anna Wong Tonny Soehartono Scott Stanley Timothy O’Brien With further contributions from Robert Inger, Muchamad Indrawan, Kuswata Kartawinata, Bas van Balen, Gabriella Fredriksson, Rona Dennis, Stephan Wulffraat, Will Duckworth and Tigga Kingston © 2005 by CIFOR and UNESCO All rights reserved. Published in 2005 Printed in Indonesia Printer, Jakarta Design and layout by Catur Wahyu and Gideon Suharyanto Cover photos (from left to right): Large mature trees found in primary forest provide various key habitat functions important for wildlife. (Photo by Herwasono Soedjito) An orphaned Bornean Gibbon (Hylobates muelleri), one of the victims of poor-logging and illegal hunting. (Photo by Kimabajo) Roads lead to various impacts such as the fragmentation of forest cover and the siltation of stream— other impacts are associated with improved accessibility for people. (Photo by Douglas Sheil) This book has been published with fi nancial support from UNESCO, ITTO, and SwedBio. The authors are responsible for the choice and presentation of the facts contained in this book and for the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of CIFOR, UNESCO, ITTO, and SwedBio and do not commit these organisations. -

"Restorative Justice" in Conflict Resolution Forest Resources Management

332 COLLABORATIVE (PARTNERSHIP) AS A FORM OF "RESTORATIVE JUSTICE" IN CONFLICT RESOLUTION FOREST RESOURCES MANAGEMENT Agus Surono Faculty of Law, Universitas Al Azhar Indonesia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Conflict management of forest resources among communities around forest areas often occur in va- rious regions, particularly in some national parks and forest management as Perhutani in Java and Inhutani outside Java. These conflicts indicate the forest resources management has not effectively made a positive impact in improving communities welfare around forest areas. Although the pro- visions of Article 3 in conjunction with Article 68 of Law No. 41 of 1999 on Forestry, provide the basis for communities around the forest rights of forest areas, but in reality there are still people around forest areas that do not enjoy such rights and it is this which often leads to conflicts in the management of forest resources. In the event of conflict, the solution can be done collaboratively (partnership) which is one form of restorative justice is an alternative dispute resolution (ADR). Keywords: collaborative, conflict, restorative justice, forest resources. Abstrak Konflik pengelolaan sumber daya hutan antara masyarakat sekitar kawasan hutan sering terjadi di berbagai daerah, terutama terjadi di beberapa taman nasional dan pengelolaan hutan oleh Perhutani di Jawa dan Inhutani di luar Jawa. Konflik ini menunjukkan pengelolaan sumber daya hutan masih belum efektif memberikan dampak positif dalam meningkatkan kesejahteraan masyarakat di sekitar kawasan hutan. Meskipun ketentuan Pasal 3 jo Pasal 68 Undang-Undang Nomor 41 Tahun 1999 tentang Kehutanan, memberikan hak bagi masyarakat sekitar kawasan hutan, namun pada kenyataannya masih ada masyarakat di sekitar kawasan hutan yang tidak menikmati hak-hak tersebut dan hal inilah yang sering menyebabkan konflik dalam pengelolaan sumber daya hutan.