The Aristotelian Doctrine of Homonyma in the Categories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aelius Aristides , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 27:3 (1986:Autumn) P.279

BLOIS, LUKAS DE, The "Eis Basilea" [Greek] of Ps.-Aelius Aristides , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 27:3 (1986:Autumn) p.279 The Ei~ BauLAea of Ps.-Aelius Aristides Lukas de Blois HE AUTHENTICITY of a speech preserved under the title El~ Ba T utAia in most MSS. of Aelius Aristides (Or. 35K.) has long been questioned.1 It will be argued here that the speech is a basilikos logos written by an unknown author of the mid-third century in accordance with precepts that can be found in the extant rhetorical manuals of the later Empire. Although I accept the view that the oration was written in imitation of Xenophon's Agesilaus and Isoc rates' Evagoras, and was clearly influenced by the speeches of Dio Chrysostom on kingship and Aristides' panegyric on Rome,2 I offer support for the view that the El~ BautAia is a panegyric addressed to a specific emperor, probably Philip the Arab, and contains a political message relevant to a specific historical situation. After a traditional opening (§ § 1-4), the author gives a compar atively full account of his addressee's recent accession to the throne (5-14). He praises the emperor, who attained power unexpectedly while campaigning on the eastern frontier, for doing so without strife and bloodshed, and for leading the army out of a critical situation back to his own territory. The author mentions in passing the em peror's education (1lf) and refers to an important post he filled just before his enthronement-a post that gave him power, prepared him for rule, and gave him an opportunity to correct wrongs (5, 13). -

000 (London, 2009)

Aristotle from York to Basra An investigation into the simultaneous study of Aristotle’s Categories in the Carolingian, the Byzantine and the Abbasid worlds by Erik Hermans A dissertation submitted in partial ful@illment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute for the Study of the AnCient World New York University May, 2016 _________________________ Robert Hoyland © Erik Hermans All Rights Reserved, 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the produCt of a new and interdisCiplinary graduate program at the Institute for the Study of the AnCient World (ISAW) at New York University. Without the vision and generosity of Leon Levy and Shelby White ISAW would not have existed and this dissertation would not have been written. I am therefore greatly indebted to these philanthropists. At ISAW I was able to Create my own graduate CurriCulum, whiCh allowed me to expand my horizon as a ClassiCist and explore the riChness of Western Europe, Byzantium and the Middle East in the early medieval period. My aCademiC endeavors as a graduate student would not have been successful without the reliable, helpful and impeCCable guidanCe of Roger Bagnall. Without him AmeriCan aCademia would still be a labyrinth for me. I Consider myself very fortunate to have an interdisCiplinary Committee of supervisors from different institutions. Helmut Reimitz of PrinCeton University and John Duffy of Harvard University have voluntarily Committed themselves to the supervision of both my Comprehensive exams and my dissertation. I would like to thank them deeply for their time and assistanCe. However, I am most indebted to my primary advisor, Robert Hoyland. -

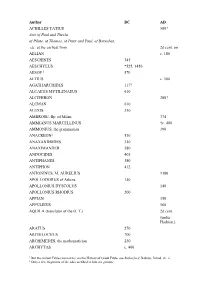

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, Etc

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, etc. at the earliest from 2d cent. on AELIAN c. 180 AESCHINES 345 AESCHYLUS *525, †456 AESOP 1 570 AETIUS c. 500 AGATHARCHIDES 117? ALCAEUS MYTILENAEUS 610 ALCIPHRON 200? ALCMAN 610 ALEXIS 350 AMBROSE, Bp. of Milan 374 AMMIANUS MARCELLINUS †c. 400 AMMONIUS, the grammarian 390 ANACREON2 530 ANAXANDRIDES 350 ANAXIMANDER 580 ANDOCIDES 405 ANTIPHANES 380 ANTIPHON 412 ANTONINUS, M. AURELIUS †180 APOLLODORUS of Athens 140 APOLLONIUS DYSCOLUS 140 APOLLONIUS RHODIUS 200 APPIAN 150 APPULEIUS 160 AQUILA (translator of the O. T.) 2d cent. (under Hadrian.) ARATUS 270 ARCHILOCHUS 700 ARCHIMEDES, the mathematician 250 ARCHYTAS c. 400 1 But the current Fables are not his; on the History of Greek Fable, see Rutherford, Babrius, Introd. ch. ii. 2 Only a few fragments of the odes ascribed to him are genuine. ARETAEUS 80? ARISTAENETUS 450? ARISTEAS3 270 ARISTIDES, P. AELIUS 160 ARISTOPHANES *444, †380 ARISTOPHANES, the grammarian 200 ARISTOTLE *384, †322 ARRIAN (pupil and friend of Epictetus) *c. 100 ARTEMIDORUS DALDIANUS (oneirocritica) 160 ATHANASIUS †373 ATHENAEUS, the grammarian 228 ATHENAGORUS of Athens 177? AUGUSTINE, Bp. of Hippo †430 AUSONIUS, DECIMUS MAGNUS †c. 390 BABRIUS (see Rutherford, Babrius, Intr. ch. i.) (some say 50?) c. 225 BARNABAS, Epistle written c. 100? Baruch, Apocryphal Book of c. 75? Basilica, the4 c. 900 BASIL THE GREAT, Bp. of Caesarea †379 BASIL of Seleucia 450 Bel and the Dragon 2nd cent.? BION 200 CAESAR, GAIUS JULIUS †March 15, 44 CALLIMACHUS 260 Canons and Constitutions, Apostolic 3rd and 4th cent. -

Sebastian Florian Weiner · Eriugenas Negative Ontologie

Sebastian Florian Weiner · Eriugenas negative Ontologie Sebastian Florian Weiner Eriugenas negative Ontologie Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung 1 1.1 Allgemeines . 1 1.2 Zum zeitlichen Entstehungsrahmen des Periphyseon . 6 1.3 Die neue Textedition . 8 1.4 Der deutungsschwere Textanfang . 9 2 Interpretation des Periphyseon, ausgehend vom Anfang 19 2.1 Der erste Satz: ein metaphysisches Fundament? . 22 2.1.1 Untersuchung der einzelnen Satzteile . 25 2.1.2 Nachdenken und Erfassen: eine epistemologische Grundunterscheidung . 26 2.1.3 Die Bedeutung des Ausdrucks ea quae sunt . 33 2.1.4 Zwei Gegenstandsklassen . 35 2.1.5 Exkurs: Ein Vergleich mit Boethius’ Naturbestim- mung . 38 2.2 Die Einteilung der Natur . 41 2.2.1 Von Natur als generale vocabulum zur Einteilung derselben . 45 2.2.2 Die Gegenstände der einzelnen Naturarten . 53 2.2.3 Der Untersuchungsplan des Werks . 59 2.3 Eine negative Ontologie . 61 2.3.1 Sein und die Aussage ›zu sein‹ . 61 2.3.2 Essentia und vere esse . 67 2.4 Der Kern der negativen Ontologie . 73 2.4.1 Dass-Sein und Was-Sein . 82 2.4.2 Das unbestimmbare subiectum . 84 2.5 Die übrigen vier Auslegungsweisen und ihre Funktion . 90 2.5.1 Die zweite Auslegungsweise . 90 2.5.2 Die dritte Auslegungsweise . 93 2.5.3 Die vierte Auslegungsweise . 96 2.5.4 Die fünfte Auslegungsweise . 98 Inhaltsverzeichnis 2.6 Ergebnisse dieser ersten Textuntersuchung . 99 2.7 Die Ontologie im ersten Buch . 101 2.7.1 Zur Unbegreiflichkeit der rationes dei und zur Theo- phanie (154–401) . 102 2.7.2 Gott als Geschöpf (402–557) . -

Boethius's Anti-Realist Arguments

c Peter King, forthcoming in Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy BOETHIUS’S ANTI-REALIST ARGUMENTS . INTRODUCTION OETHIUS opens his discussion of the problem of universals, in his second commentary on Porphyry’s Isagoge, with a destruc- tive dilemma: Genera and species either exist or are concepts; B but they can neither exist nor be soundly conceived; therefore the inquiry into them should be abandoned (in Isag.maior .). Boethius’s strategy to get around this dilemma is well known. He follows the lead of Alexander of Aphrodisias, distinguishing several ways in which genera and species can be conceived, and he argues that at least one way involves no falsity. Hence it is possible to conceive genera and species soundly, and Porphyry’s inquiry into them is therefore not futile after all (.). Boethius thus resolves the second horn of his opening dilemma. Yet he allows the first horn of the dilemma, the claim that genera and species cannot exist, to stand. The implication is that he takes his arguments for this claim to be sound. If so, this would be a philosophically exciting and significant result, well worth exploring in its own right. Yet there is no consensus, either medieval or modern, on precisely what Boethius’s arguments are, or even how many arguments he offers, much less on their soundness.1 One reason for the lack of consensus is that Boethius’s arguments must be understood in light of their ancient philosophical sources ∗ All translations are mine except as noted. I was first led to this corner of the history of metaphysics by Michael Frede, whose keen interest in Porphyry and Boethius stimulated my own. -

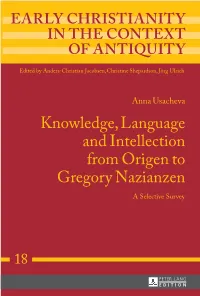

Knowledge, Language and Intellection from Origen to Gregory Nazianzen a Selective Survey

Epistemological theories of the patristic authors seldom attract attention of the re- searchers. This unfortunate status quo contrasts with a crucial place of the theory EARLY CHRISTIANITY of knowledge in the thought of such prominent authors as Origen and the Cappa- ECCA 18 docian fathers. This book surveys the patristic epistemological discourse in its vari- IN THE CONTEXT ous settings. In the context of the Church history it revolves around the Eunomian controversy, Eunomius’ language theory and Gregory Nazianzen’s cognitive theory, where the ideas of Apostle Paul were creatively combined with the Peripatetic teach- OF ANTIQUITY ing. In the framework of Biblical exegesis, it touches upon the issues of the textual criticism of the Homeric and Jewish scholarship, which had significantly shaped Origen’s paradigm of the Biblical studies. Edited by Anders-Christian Jacobsen, Christine Shepardson, Jörg Ulrich Anna Usacheva Knowledge, Language and Intellection from Origen to Gregory Nazianzen A Selective Survey Anna Usacheva holds a PhD in Classical Philology and was a lecturer in Patristics and Ancient Languages at St. Tikhon Orthodox University (Moscow, Russia). Cur- rently, she is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of Intellection and Language Knowledge, · Usacheva Anna Theology, Aarhus University (Denmark). 18 ISBN 978-3-631-73109-3 Epistemological theories of the patristic authors seldom attract attention of the re- searchers. This unfortunate status quo contrasts with a crucial place of the theory EARLY CHRISTIANITY of knowledge in the thought of such prominent authors as Origen and the Cappa- ECCA 18 docian fathers. This book surveys the patristic epistemological discourse in its vari- IN THE CONTEXT ous settings. -

Unknown God, Known in His Activities EUROPEAN STUDIES in THEOLOGY, PHILOSOPHY and HISTORY of RELIGIONS Edited by Bartosz Adamczewski

18 What can man know about God? This question became one of the main Tomasz Stępień / problems during the 4th-century Trinitarian controversy, which is the focus Karolina Kochańczyk-Bonińska of this book. Especially during the second phase of the conflict, the claims of Anomean Eunomius caused an emphatic response of Orthodox writers, mainly Basil of Caesarea and Gregory of Nyssa. Eunomius formulated two ways of theology to show that we can know both the substance (ousia) and activities (energeiai) of God. The Orthodox Fathers demonstrated that we can know only the external activities of God, while the essence is entirely incom- prehensible. Therefore the 4th-century discussion on whether the Father and the Son are of the same substance was the turning point in the development Unknown God, of negative theology and shaping the Christian conception of God. Known Unknown God, Known God, Unknown in His Activities in His Activities Incomprehensibility of God during the Trinitarian Controversy of the 4th Century stopibhuarly Jewish Sources Tomasz Stępień is Associate Professor at the Faculty of Theology, Cardi- Karolina Kochańczyk-Bonińska · nal Stefan Wyszyński University in Warsaw. He researches and publishes / on Ancient Philosophy, Early Christian Philosophy, Natural Theology and Philosophy of Religion. European Studies in Theology, Karolina Kochańczyk-Bonińska is Assistant Professor at the Institute of Philosophy and History of Religions the Humanities and Social Sciences, War Studies University in Warsaw. She researches and publishes on Early Christian Philosophy and translates Edited by Bartosz Adamczewski patristic texts. Stępień Tomasz ISBN 978-3-631-75736-9 EST_018 275736-Stepien_TL_A5HC 151x214 globalL.indd 1 04.07.18 17:07 18 What can man know about God? This question became one of the main Tomasz Stępień / problems during the 4th-century Trinitarian controversy, which is the focus Karolina Kochańczyk-Bonińska of this book. -

SIMPLICIUS, in CAT., P. 1,3–3,17 KALBFLEISCH an Important

SIMPLICIUS, IN CAT., P.1,3–3,17 KALBFLEISCH An Important Contribution to the History of the Ancient Commentary1 The last few decades have witnessed a strong renewal of inter- est in the history of the ancient and medieval commentary. The im- posing series of translations of the ancient commentaries on Aristotle inaugurated and directed by R. Sorabji is a clear indica- tion of this2. Villejuif, France, was the scene in 1999 of an Inter- national Colloquium on “The Commentary between tradition and innovation”, the acts of which were published under the direction of M.-O. Goulet-Cazé. At Bochum, Germany, a “Graduiertenkol- leg” under the direction of W.Geerlings worked for six years on “Der Kommentar in Antike und Mittelalter”, and a collection of contributions to this workshop was edited by W.Geerlings and Chr. Schultze in 2002 (Leiden-Boston-Köln). In these publications, three articles3 were devoted specifically to the tradition of the Neo- platonic commentaries. None of them deals with the beginning of 1) Translated from the French by Michael Chase. 2) Many translations of commentaries on Aristotle have already appeared in this series. For Simplicius, cf. also I. Hadot, Simplicius – Commentaire sur le Manuel d’Épictète, Introduction et édition critique du texte grec, Leiden / New York / Köln 1996 (Philosophia Antiqua, vol. LXVI), and Simplicius – Commentaire sur le Manuel d’Épictète, chap. I à XXIX (with French translation), Paris 2001, as well as the works cited note 3. I shall not cite here the editions and translations of the Neoplatonic commentaries on Plato, also very numerous, which took on re- newed vigor after the translations of A. -

Athens and Byzantium: Platonic Political Philosophy in Religious Empire Jeremiah Heath Russell Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Athens and Byzantium: Platonic political philosophy in religious empire Jeremiah Heath Russell Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Russell, Jeremiah Heath, "Athens and Byzantium: Platonic political philosophy in religious empire" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2978. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2978 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. ATHENS AND BYZANTIUM: PLATONIC POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY IN RELIGIOUS EMPIRE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Political Science by Jeremiah Heath Russell B.A., The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2001 M. Div., The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, 2003 M.A., Baylor University, 2006 August, 2010 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was not possible without the numerous sources of support that I received throughout my graduate studies. First, I must thank my major professor, James R. Stoner, Jr., whose encouragement was there from my earliest days at LSU until the completion of this program. He is a model intellectual with an uncanny ability to identify the heart of the matter and to offer penetrating questions. My commitment to the importance of the political, reflected in this dissertation, I owe to him. -

Porphyry and Plotinus' Metaphysics

forthcoming in G. Karamanolis and A. Sheppard, eds. Studies in Porphyry for the most part purely Plotinian and often taken verbatim or nearly so from the Enneads, as can Porphyry and Plotinus’ Metaphysics 4 Steven K. Strange be seen from the excellent apparatus fontium in Lamberz’s Teubner edition: what is supplied by Emory University Porphyry himself seems intended to help clarify and only occasionally to expand upon his Plotinian basis.5 If this picture of the Sententiae as a sort of handbook, like the Encheiridion of As editor and popularizer of his teacher Plotinus, as a founding figure of Neoplatonism, Epictetus, intended for Plotinian progressors, is correct, then any originality or innovation to be and as an important commentator on Plato and Aristotle, Porphyry deserves to be considered a found in the work will have been unintentional on the part of its author, and it is therefore not major figure in the history of philosophy. But though a first-rate scholar of philosophy as well as surprising to find the work cited somewhat rarely in discussions of Porphyry’s own thought. of other fields—and as such a worthy successor to his first tutor in Platonic philosophy, the A.C. Lloyd in his important article in the Cambridge history of later Greek and early medieval learned Longinus—it is much less clear to what extent Porphyry can be considered an original philosophy6 did claim to find in the Sententiae a new conception of the soul’s return to the contributor to the development of ancient philosophy.1 Indeed, much of Porphyry’s extant work intelligible realm (by abstracting in thought from all logical particularity),7 but he admits that this consists of excerpts, often extensive verbatim excerpts, from earlier writers: this is true of his De conception seems to have been suggested to Porphyry by the final chapter of Ennead VI.4-5, abstinentia, of his Pythagoras biography,2 and of his philosophical epistle to his wife, the Ad Plotinus’ treatise on the omnipresence of Being in the sensible world (VI.5.12). -

A STUDY in EARLY MEDIEVAL MEREOLOGY: BOETHIUS, ABELARD, and PSEUDO-JOSCELIN DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of

A STUDY IN EARLY MEDIEVAL MEREOLOGY: BOETHIUS, ABELARD, AND PSEUDO-JOSCELIN DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrew W. Arlig, M.A. The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Tamar Rudavsky, Adviser Professor Peter O. King ______________________________ Professor Allan Silverman Adviser Graduate Program in Philosophy Copyright by Andrew W. Arlig 2005 ABSTRACT The study of parts and wholes, or mereology, occupies two of the best philosophical minds of twelfth-century Europe, Abelard and Pseudo-Joscelin. But the contributions of Abelard and Pseudo-Joscelin cannot be adequately assessed until we come to terms with the mereological doctrines of the sixth century philosopher Boethius. Apart from providing the general mereological background for the period, Boethius influences Abelard and Pseudo-Joscelin in two crucial respects. First, Boethius all but omits mention of the classical Aristotelian concept of form. Second, Boethius repeatedly highlights a rule which says that if a part is removed, the whole is removed as well. Abelard makes many improvements upon Boethius. His theory of static identity accounts for the relations of sameness and difference that hold between a thing and its part. His theory of identity also provides a solution to the problem of material constitution. With respect to the problem of persistence, Abelard assimilates Boethius’ rule and proposes that the loss of any part entails the annihilation of the whole. More precisely, Abelard thinks that the matter of things suffers annihilation upon the gain or loss of even one part. -

Iamblichus and the Foundations of Late Platonism Ancient Mediterranean and Medieval Texts and Contexts

Iamblichus and the Foundations of Late Platonism Ancient Mediterranean and Medieval Texts and Contexts Editors Robert M. Berchman Jacob Neusner Studies in Platonism, Neoplatonism, and the Platonic Tradition Edited by Robert M. Berchman Dowling College and Bard College John F. Finamore University of Iowa Editorial Board JOHN DILLON (Trinity College, Dublin) – GARY GURTLER (Boston College) JEAN-MARC NARBONNE (Laval University, Canada) VOLUME 13 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/spnp Iamblichus and the Foundations of Late Platonism Edited by Eugene Afonasin John Dillon John F. Finamore LEIDEN • BOSTON 2012 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Iamblichus and the foundations of late platonism / edited by Eugene Afonasin, John Dillon, John F. Finamore. p. cm. – (Ancient Mediterranean and medieval texts and contexts, ISSN 1871-188X ; v. 13) Includes index. ISBN 978-90-04-18327-8 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Iamblichus, ca. 250-ca. 330. 2. Neoplatonism. I. Afonasin, E. V. (Evgenii Vasil?evich) II. Dillon, John M. III. Finamore, John F., 1951- B669.Z7I26 2012 186'.4–dc23 2012007354 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.nl/brill-typeface. ISSN 1871-188X ISBN 978 90 04 18327 8 (hardback) ISBN 978 90 04 23011 8 (e-book) Copyright 2012 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhof Publishers. All rights reserved.