Porphyry and Plotinus' Metaphysics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aelius Aristides , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 27:3 (1986:Autumn) P.279

BLOIS, LUKAS DE, The "Eis Basilea" [Greek] of Ps.-Aelius Aristides , Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, 27:3 (1986:Autumn) p.279 The Ei~ BauLAea of Ps.-Aelius Aristides Lukas de Blois HE AUTHENTICITY of a speech preserved under the title El~ Ba T utAia in most MSS. of Aelius Aristides (Or. 35K.) has long been questioned.1 It will be argued here that the speech is a basilikos logos written by an unknown author of the mid-third century in accordance with precepts that can be found in the extant rhetorical manuals of the later Empire. Although I accept the view that the oration was written in imitation of Xenophon's Agesilaus and Isoc rates' Evagoras, and was clearly influenced by the speeches of Dio Chrysostom on kingship and Aristides' panegyric on Rome,2 I offer support for the view that the El~ BautAia is a panegyric addressed to a specific emperor, probably Philip the Arab, and contains a political message relevant to a specific historical situation. After a traditional opening (§ § 1-4), the author gives a compar atively full account of his addressee's recent accession to the throne (5-14). He praises the emperor, who attained power unexpectedly while campaigning on the eastern frontier, for doing so without strife and bloodshed, and for leading the army out of a critical situation back to his own territory. The author mentions in passing the em peror's education (1lf) and refers to an important post he filled just before his enthronement-a post that gave him power, prepared him for rule, and gave him an opportunity to correct wrongs (5, 13). -

The Aristotelian Doctrine of Homonyma in the Categories

JOHN P. ANTON THE ARISTOTELIAN DOCTRINE OF HOMONYMA IN THE CATEGORIES AND ITS PLATONIC ANTECEDENTS * ι The Aristotelian doctrine of h ο m ο η y m a is of particular historical in terest at least for the following reasons : (1) It appears that the meaning of homo n.y m a was seriously debated in Aristotle's times aud that his own formu lation was but one among many others. Evidently, there were other platonizing thinkers in the Academy who had formulated their own variants. According to ancient testimonies, the definition which Speusippus propounded proved to be quite influential in later times 1. (2) The fact that Aristotle chose to open the Categories with a discussion, brief as it is, on the meaning of homonyma, synonyma, and paronym a, attests to the significance]he attached to this preli minary chapter. Furthermore, there is general agreement among all the commen tators on the relevance of the first chapter of the Categories to the doctri ne of the categories. (3) The corpus affords ample internal evidence that the doctrine of homonyma figures largely in Aristotle's various discussions on the nature of first principles and his method of metaphysical analysis. This being the case, it is clear that Aristotle considered this part of his logical theory to have applications beyond the limited scope of what is said in the Cate gories. Since we do not know the actual order of Aristotle's writings it is next to the impossible to decide which formulation came first. It remains a fact that Aristotle discusses cases of homonyma and their causes as early as the Sophistici * To παρόν άρθρον εστάλη υπό τοϋ συγγραφέως, φίλου του αειμνήστου Κ. -

000 (London, 2009)

Aristotle from York to Basra An investigation into the simultaneous study of Aristotle’s Categories in the Carolingian, the Byzantine and the Abbasid worlds by Erik Hermans A dissertation submitted in partial ful@illment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute for the Study of the AnCient World New York University May, 2016 _________________________ Robert Hoyland © Erik Hermans All Rights Reserved, 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the produCt of a new and interdisCiplinary graduate program at the Institute for the Study of the AnCient World (ISAW) at New York University. Without the vision and generosity of Leon Levy and Shelby White ISAW would not have existed and this dissertation would not have been written. I am therefore greatly indebted to these philanthropists. At ISAW I was able to Create my own graduate CurriCulum, whiCh allowed me to expand my horizon as a ClassiCist and explore the riChness of Western Europe, Byzantium and the Middle East in the early medieval period. My aCademiC endeavors as a graduate student would not have been successful without the reliable, helpful and impeCCable guidanCe of Roger Bagnall. Without him AmeriCan aCademia would still be a labyrinth for me. I Consider myself very fortunate to have an interdisCiplinary Committee of supervisors from different institutions. Helmut Reimitz of PrinCeton University and John Duffy of Harvard University have voluntarily Committed themselves to the supervision of both my Comprehensive exams and my dissertation. I would like to thank them deeply for their time and assistanCe. However, I am most indebted to my primary advisor, Robert Hoyland. -

Documents Click Here & Upgrade Expanded Features PDF Unlimited Pages Completedocuments

Click Here & Upgrade Expanded Features PDF Unlimited Pages CompleteDocuments Click Here & Upgrade Expanded Features PDF Unlimited Pages CompleteDocuments “THE FATE OF THIS POOR WOMAN”: MEN, WOMEN, AND INTERSUBJECTIVITY IN MOLL FLANDERS AND ROXANA A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Peter Christian Marbais May, 2005 Click Here & Upgrade Expanded Features PDF Unlimited Pages CompleteDocuments Click Here & Upgrade Expanded Features PDF Unlimited Pages CompleteDocuments Dissertation written by Peter Christian Marbais B.A., Ohio Wesleyan University, 1995 M.A., Kent State University, 1998 Ph.D., Kent State University, 2005 Approved by Vera J. Camden, Professor of English, Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Donald M. Hassler, Professor of English, Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Thomas J. Hines, Emeritus Professor of English Ute J. Dymon, Professor of Geography Accepted by Ronald J. Corthell, Chair, Department of English Darrell Turnidge, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii Click Here & Upgrade Expanded Features PDF Unlimited Pages CompleteDocuments Click Here & Upgrade Expanded Features PDF Unlimited Pages CompleteDocuments TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS…………………………………….…………………….........iv CHAPTER INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………..……….1 I. DEFOE AND FATE…………………...………………………………………25 II. DEFOE’S WOMEN IN THE MYTHOS OF FATE AND INTERSUBJECTIVITY……………………………..………………...…….77 III. MUTUAL RECOGNITION WITHIN THE FATAL MATRIX AND BETWEEN -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY I. PSEUDO-D10NYSIUS THE AREOPAG1TE I. The Writings of Pseudo-Dionysius Modern Editions (I) S. Dionysii Areopagitae opera omnia quae exstant et commentarii quibus illustrantur, studio et opera Balthasaris Corderii, S. J., Patrologia Graeca 3, ed. J.-P. Migne, Text from the Edition of 1634 (Paris, 1856). Because of the immense difficulties presented by the manuscript tradition, the text of the ten Letters in this edition has not been superseded. The notes from M. J . Pinard's lifelong work have unfortunately been neither edited nor pub lished. (2) La hierarchie cileste, Traduction et Notes par M. de Gandillac, Etude et texte critiques par G. Heil, Introduction de Denys I'Areopagite par R. Roques, Collection Sources Chretiennes 58 (Paris, 1956). (3) Pseudo-Dionysii Areopagitae De caelesti hierarchia, in usum studiosae iuventutis, ed. P. Hendrix, Textus Minores XXV (Leiden, 1959). [Hendrix reproduces the text of (2)]. (4) S . Thomae Aquinatis, in librum Beati Dionysii "De Divinis Nominibus" expositio (Rome, 1950) [Improved text of On Divine Names, ed. C. Pera]. (5) [Anonymous], La TMologie Mystique, in La Vie Spirituelle 22 (1930), pp. 129-1 36. (6) Campbell, T. L., Dionysius the Pseudo-Areopagite: The Ecclesiastical Hierarchy, Translated and Annotated, Studies in Sacred Theology, S. S. 83 (Washington, 1955). (7) Darboy, G., Oeuvres de Saint Denys l'Areopagite traduites du grec; prece dees d'une introduction ou l'an discute l'authenticite de ces livres, et ou l'on expose la doctrine qu'ils renferment, et l'influence qu'ils ont exercee au moyen age (Paris, 1845). (8) Dulac, ]., Oeuvres de Saint Denys I'Areopagite, traduites du grec en fran<;:ais, avec Prolegomimes, Manchettes, Notes, Table analytique et alphabHique, Table detaillee des matieres .. -

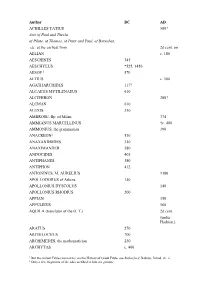

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, Etc

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, etc. at the earliest from 2d cent. on AELIAN c. 180 AESCHINES 345 AESCHYLUS *525, †456 AESOP 1 570 AETIUS c. 500 AGATHARCHIDES 117? ALCAEUS MYTILENAEUS 610 ALCIPHRON 200? ALCMAN 610 ALEXIS 350 AMBROSE, Bp. of Milan 374 AMMIANUS MARCELLINUS †c. 400 AMMONIUS, the grammarian 390 ANACREON2 530 ANAXANDRIDES 350 ANAXIMANDER 580 ANDOCIDES 405 ANTIPHANES 380 ANTIPHON 412 ANTONINUS, M. AURELIUS †180 APOLLODORUS of Athens 140 APOLLONIUS DYSCOLUS 140 APOLLONIUS RHODIUS 200 APPIAN 150 APPULEIUS 160 AQUILA (translator of the O. T.) 2d cent. (under Hadrian.) ARATUS 270 ARCHILOCHUS 700 ARCHIMEDES, the mathematician 250 ARCHYTAS c. 400 1 But the current Fables are not his; on the History of Greek Fable, see Rutherford, Babrius, Introd. ch. ii. 2 Only a few fragments of the odes ascribed to him are genuine. ARETAEUS 80? ARISTAENETUS 450? ARISTEAS3 270 ARISTIDES, P. AELIUS 160 ARISTOPHANES *444, †380 ARISTOPHANES, the grammarian 200 ARISTOTLE *384, †322 ARRIAN (pupil and friend of Epictetus) *c. 100 ARTEMIDORUS DALDIANUS (oneirocritica) 160 ATHANASIUS †373 ATHENAEUS, the grammarian 228 ATHENAGORUS of Athens 177? AUGUSTINE, Bp. of Hippo †430 AUSONIUS, DECIMUS MAGNUS †c. 390 BABRIUS (see Rutherford, Babrius, Intr. ch. i.) (some say 50?) c. 225 BARNABAS, Epistle written c. 100? Baruch, Apocryphal Book of c. 75? Basilica, the4 c. 900 BASIL THE GREAT, Bp. of Caesarea †379 BASIL of Seleucia 450 Bel and the Dragon 2nd cent.? BION 200 CAESAR, GAIUS JULIUS †March 15, 44 CALLIMACHUS 260 Canons and Constitutions, Apostolic 3rd and 4th cent. -

Natural Theology in the Patristic Period Wayne Hankey Chapter Three of the Oxford Handbook of Natural Theology Edited Russell Re Manning Oxford University Press 2012

Natural Theology in the Patristic Period Wayne Hankey Chapter Three of The Oxford Handbook of Natural Theology Edited Russell Re Manning Oxford University Press 2012 The centrality of natural theology in this period and its inescapable formation of what succeeds are indicated by the multiple forms it takes throughout its extent in Hellenic, Jewish, and Christian philosophies, religious practices, and theologies. Commonly, the term, as used to refer to an apologetic or instrument presupposed by or leading to revealed religion and theology, makes no distinction between the forms of philosophy. Moreover, when those listed as “philosophers” in our histories touch on theological or religious matter, they are usually treated as if what they wrote was all “natural”, in the sense of coming from inherent human capacity, as opposed to what is inspired or gracious. Packing the natural theology of what we are calling “the Patristic Period” into such crudely undifferentiated lumps moulded by later binary schematizing destroys what it most distinctively accomplished. It not only produced the new language of metaphysics and the supernatural, 1 but also thought through how nature and what is beyond it interpenetrated one another. The Hellenic, Jewish, and Christian philosophers and theologians of the period, themselves frequently bridging the natural / supernatural divide in their “divine” miracle working or at least consecrated persons, took what was diversely established within Classical Antiquity to build hierarchically connected levels and kinds -

The Routledge Handbook of Neoplatonism the Alexandrian

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 25 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK The Routledge Handbook of Neoplatonism Pauliina Remes, Svetla Slaveva-Griffin The Alexandrian classrooms excavated and sixth-century philosophy teaching Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315744186.ch3 Richard Sorabji Published online on: 30 Apr 2014 How to cite :- Richard Sorabji. 30 Apr 2014, The Alexandrian classrooms excavated and sixth-century philosophy teaching from: The Routledge Handbook of Neoplatonism Routledge Accessed on: 25 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9781315744186.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 The Alexandrian classrooms excavated and sixth-century philosophy teaching Richard Sorabji It was announced in 2004 that the Polish archaeological team under Grzegorz Majcherek had identifi ed the surprisingly well-preserved lecture rooms of the sixth-century Alexandrian school.1 Th is was a major archaeological discovery.2 Although the fi rst few rooms had been excavated twenty-fi ve years earlier, identifi cation has only now become possible. -

Rhetoric and Platonism in Fifth-Century Athens

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Philosophy Faculty Research Philosophy Department 2014 Rhetoric and Platonism in Fifth-Century Athens Damian Caluori Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/phil_faculty Part of the Philosophy Commons Repository Citation Caluori, D. (2014). Rhetoric and Platonism in fifth-century Athens. In R. C. Fowler (Ed.), Plato in the third sophistic (pp. 57-72). De Gruyter. This Contribution to Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Damian Caluori (Trinity University) Rhetoric and Platonism in Fifth-Century Athens There are reasons to believe that relations between Platonism and rhetoric in Athens during the fifth century CE were rather close.Z Both were major pillars of pagan cul- ture, or paideia, and thus essential elements in the defense of paganism against in- creasingly powerful and repressive Christian opponents. It is easy to imagine that, under these circumstances, paganism was closing ranks and that philosophers and orators united in their efforts to save traditional ways and values. Although there is no doubt some truth to this view, a closer look reveals that the relations be- tween philosophy and rhetoric were rather more complicated. In what follows, I will discuss these relations with a view to the Platonist school of Athens. By “the Platon- ist school of Athens” I mean the Platonist school founded by Plutarch of Athens in the late fourth century CE, and reaching a famous end under the leadership of Dam- ascius in 529.X I will first survey the evidence for the attitudes towards rhetoric pre- vailing amongst the most important Athenian Platonists of the time. -

1 Florian Marion the Ἐξαίφνης in the Platonic Tradition: from Kinematics to Dynamics (Draft) Studies on Platonic 'The

F. Marion – The ἐξαίφνης in the Platonic Tradition: from Kinematics to Dynamics Florian Marion The ἐξαίφνης in the Platonic Tradition: from Kinematics to Dynamics (Draft) Studies on Platonic ‘Theoria motus abstracti’ are often focused on dynamics rather than kinematics, in particular on psychic self-motion. This state of affairs is, of course, far from being a bland academic accident: according to Plato, dynamics is the higher science while kinematics is lower on the ‘scientific’ spectrum1. Furthermore, when scholars investigate Platonic abstract kinematics, in front of them there is a very limited set of texts2. Among them, one of the most interesting undoubtedly remains a passage of Parmenides in which Plato challenges the puzzle of the ‘instant of change’, namely the famous text about the ‘sudden’ (τὸ ἐξαίφνης). Plato’s ἐξαίφνης actually is a terminus technicus and a terminus mysticus at once3, in such a way that from Antiquity until today this Platonic concept has been interpreted in very different fashions, either in a physical fashion or in a mystical one. Nevertheless, it has not been analysed how those two directions have been already followed by the Platonic Tradition. So, the aim of this paper is to provide some acquaintance with the exegetical history of ἐξαίφνης inside the Platonic Tradition, from Plato to Marsilio Ficino, by way of Middle Platonism and Greek Neoplatonism. After exposing Plato’s argument of Parm, 156c-157b and its various interpretations (1), I shall investigate the ways by which Middle Platonists (especially Taurus) and Early Neoplatonists as Plotinus and Iamblichus have understood Plato’s use of ἐξαίφνης (2), and finally how this notion had been transferred from kinematics to dynamics in Later Neoplatonism (3). -

Sebastian Florian Weiner · Eriugenas Negative Ontologie

Sebastian Florian Weiner · Eriugenas negative Ontologie Sebastian Florian Weiner Eriugenas negative Ontologie Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung 1 1.1 Allgemeines . 1 1.2 Zum zeitlichen Entstehungsrahmen des Periphyseon . 6 1.3 Die neue Textedition . 8 1.4 Der deutungsschwere Textanfang . 9 2 Interpretation des Periphyseon, ausgehend vom Anfang 19 2.1 Der erste Satz: ein metaphysisches Fundament? . 22 2.1.1 Untersuchung der einzelnen Satzteile . 25 2.1.2 Nachdenken und Erfassen: eine epistemologische Grundunterscheidung . 26 2.1.3 Die Bedeutung des Ausdrucks ea quae sunt . 33 2.1.4 Zwei Gegenstandsklassen . 35 2.1.5 Exkurs: Ein Vergleich mit Boethius’ Naturbestim- mung . 38 2.2 Die Einteilung der Natur . 41 2.2.1 Von Natur als generale vocabulum zur Einteilung derselben . 45 2.2.2 Die Gegenstände der einzelnen Naturarten . 53 2.2.3 Der Untersuchungsplan des Werks . 59 2.3 Eine negative Ontologie . 61 2.3.1 Sein und die Aussage ›zu sein‹ . 61 2.3.2 Essentia und vere esse . 67 2.4 Der Kern der negativen Ontologie . 73 2.4.1 Dass-Sein und Was-Sein . 82 2.4.2 Das unbestimmbare subiectum . 84 2.5 Die übrigen vier Auslegungsweisen und ihre Funktion . 90 2.5.1 Die zweite Auslegungsweise . 90 2.5.2 Die dritte Auslegungsweise . 93 2.5.3 Die vierte Auslegungsweise . 96 2.5.4 Die fünfte Auslegungsweise . 98 Inhaltsverzeichnis 2.6 Ergebnisse dieser ersten Textuntersuchung . 99 2.7 Die Ontologie im ersten Buch . 101 2.7.1 Zur Unbegreiflichkeit der rationes dei und zur Theo- phanie (154–401) . 102 2.7.2 Gott als Geschöpf (402–557) . -

Table of Contents More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-76440-7 - The Cambridge History of Philosophy in Late Antiquity, Volume I Edited by Lloyd P. Gerson Table of Contents More information CONTENTS VOLUME I List of contributors page xi List of maps xv General introduction 1 lloyd p. gerson I Philosophy in the later Roman Empire Introduction to Part I 11 1 The late Roman Empire from the Antonines to Constantine 13 elizabeth depalma digeser 2 The transmission of ancient wisdom: texts, doxographies, libraries 25 gabor´ betegh 3 Cicero and the New Academy 39 carlos levy´ 4 Platonism before Plotinus 63 harold tarrant 5 The Second Sophistic 100 ryan fowler 6 Numenius of Apamea 115 mark edwards 7 Stoicism 126 brad inwood v © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-76440-7 - The Cambridge History of Philosophy in Late Antiquity, Volume I Edited by Lloyd P. Gerson Table of Contents More information vi Contents 8 Peripatetics 140 robert w. sharples 9 The Chaldaean Oracles 161 john f. finamore and sarah iles johnston 10 Gnosticism 174 edward moore and john d. turner 11 Ptolemy 197 jacqueline feke and alexander jones 12 Galen 210 r. j. hankinson II The first encounter of Judaism and Christianity with ancient Greek philosophy Introduction to Part II 233 13 Philo of Alexandria 235 david winston 14 Justin Martyr 258 denis minns 15 Clement of Alexandria 270 catherine osborne 16 Origen 283 emanuela prinzivalli III Plotinus and the new Platonism Introduction to Part III 299 17 Plotinus 301 dominic j. o’meara 18 Porphyry and his school 325 andrew smith 19 Iamblichus of Chalcis and his school 358 john dillon © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-76440-7 - The Cambridge History of Philosophy in Late Antiquity, Volume I Edited by Lloyd P.