Before-And-After Studies of New Starts Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bringing Regional Rail Service to the Historic Cotton Belt Corridor DART Current and Future Rail Services

SILVER LINE REGIONAL RAIL GROUNDBREAKING COMMEMORATIVE EDITION Bringing Regional Rail Service to the Historic Cotton Belt Corridor DART Current and Future Rail Services NW PLANO PARK & RIDE PLANO PARKER ROAD To Denton JACK HATCHELL DOWNTOWN PLANO TRANSIT CTR. Preside SHILOH nt G 12TH STREET ROAD e sh Turnpike (future) o r g e Bu Dallas North Tollway CITYLINE/BUSH NORTH CARROLLTON/FRANKFORD UT DALLAS GALATYN PARK TRINITY MILLS CARROLLTON ADDISON KNOLL TRAIL RICHARDSON ARAPAHO CENTER Map Legend DOWNTOWN CARROLLTON ADDISON CYPRESS WATERS TRANSIT CTR. DFW (DALLAS) SPRING VALLEY MapTo FortLegendBlue Worth Line AIRPORT FARMERS NORTH BRANCH Red Line DOWNTOWN Blue Line FARMERS BRANCH GARLAND GARLAND LBJ/CENTRAL Map LegendGreenDFW Line DFW DOWNTOWN Red Line ROWLETT AIRPORT AIRPORT FOREST LANE FOREST/JUPITER OrangeBlueTerminal Line B Line Terminal A Green Line HIDDEN ROYAL LANE LBJ/SKILLMAN Orange Line BELT LINE ROWLETT Red Line RIDGE Map Legend LAKE HIGHLANDS Weekdays Peak Only (future) WALNUT OrangeDFW Line IRVING CONVENTION WALNUT HILL/DENTON HILL TrinityGreen RailwayLine Express CENTER Blue Line (No Sunday Service) PARK LANE Lake Ray Orange Line NORTH LAKE LAS COLINAS S. GARLAND Hubbard Orange Line COLLEGE Red Line TRANSIT CTR. TEXRailWeekdays (Trinity Peak Metro) Only URBAN CENTER UNIVERSITY WHITE ROCK LOVERS A-Train (DCTA) Green Line BACHMAN OrangeTrinity Line Railway Express UNIVERSITY OF DALLAS PARK LANE Weekdays Peak Only (No Sunday Service) LOVE FIELD White Rock M-Line Trolley VIA BUS 524 HIGHLAND LAKE RAY Orange Line Lake TrinityTEXRail Railway (Trinity Express Metro)Inset Map LOOP 12 BURBANK PARK HUBBARD Dallas(No Sunday Streetcar Service) (future) INWOOD/LOVE FIELD SMU/MOCKINGBIRD TRANSIT CTR. -

Trinity Mills Station Market Overview

Report Trinity Mills Station Market Overview Prepared for: City of Carrollton, Texas and Dallas Area Rapid Transit Prepared by: Economic & Planning Systems, Inc. April 24, 2013 EPS #20842 Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION AND PROPERTY DESCRIPTION ................................................................. 1 Trinity Mills Station Properties .................................................................................... 1 Surrounding Land Use ............................................................................................... 3 Transportation and Access ......................................................................................... 4 Planning and Land Use Policy Context .......................................................................... 4 2. REGIONAL MARKET FRAMEWORK ................................................................................ 7 Employment Trends .................................................................................................. 7 Population Growth .................................................................................................. 12 Subject Property Demographics ................................................................................ 15 Conclusions – Regional Growth Trends ...................................................................... 17 3. TRANSIT ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT ON THE DART SYSTEM ............................................... 18 Red and Blue Lines, Northeast Dallas ....................................................................... -

Highland Park Carrollton Farmers Branch Addison

LAKE LEWISVILLE 346 348 EXCHANGE PKWY 348 LEGACY DR PARKWOOD SH 121 SHOPS AT 452 348 452 LEGACY 346346 LEGACY DR TENNYSON 347 P 183 451 208 NORTH PLANO NORTHWEST PLANO DART ON-CALL ZONE PARK AND RIDE 183, 208, 346, 347, PRESTON RD 348, 451, 452 SPRING CREEK PKWY 452 SPRING CREEK PKWY 829 LAKESIDE US-75 N. CENTRAL EXPWY. COLLIN COUNTY MARKET COMMUNITY 350 COLLEGE JUPITER RD 350 TEXAS HEALTH 451 PLANO RD PRESBYTERIAN HOSPITAL PLANO PARKER RD 452 R RD COMMUNICATIONS 347 PARKER RD PARKER ROAD STATION PARKE 350, 410, 452 183 PRESTON RD. DART ON-CALL, TI Shuttle, Texoma Express 410 CUSTER RD SHOPS AT RD COIT PARK BLVD INDEPENDENCE PARK BLVD CREEK WILLOWBEND 410 ALMA ARBOR 531 347 PARK BLVD PARK BLVD CHEYENNE 870 451 BAYLOR MEDICAL CTR. 18TH 870 AT CARROLLTON HEBRON PLANO DOWNTOWN PLANO STATION MEDICAL CENTER 870 FLEX 208 OF PLANO 15TH 15TH OHIO 14TH IN T PARKWOOD E 350 R 13TH 870 N A PLANO PKWY TI 210 COLLIN CREEK MALL ON JACK HATCHELL TRANSIT CENTER FM 544 AL P KWY 841 210, 350, 451, 452, 841 FLEX SH-121 347 210 BAYLOR REGIONAL 870 843 AVE K AVE 843 841 MEDICAL CTR. ROSEMEADE PKWY 534 841 PLANO PKWY PLANO PKWY HEBRON to Denton (operated by DCTA) 531 347 841 MARSH LUNA 350 841 410 WAL-MART 883 Fri/Sun 841 ROUND GROVE NPIKE NORTH STAR RD TIMBERGREEN H TUR NORTH CARROLLTON/FRANKFORD STATION P S BUSH TURNPIKE STATION 333 U 883 UTD Shuttle, 841-843 FLEX PEAR RIDGE PEAR B IH-35E STEMMONS FRWY. -

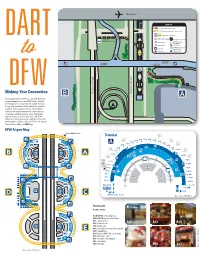

Making Your Connection

DART Rail System Map DOWNTOWN ROWLETT DFW AIRPORT STATION Open 2014 Irving Convention Center Belt Line Making Your Connection During peak times (4:30-7 a.m. and 2:15-5:30 p.m. weekday departures from DFW Airport Station), the Orange Line travels from the station through Irving, into downtown Dallas and to the northern terminus of the system at Parker Road Station in Plano. Off-peak, it follows the same path but terminates at LBJ/Central Station. Select late- night Orange Line trains will travel from DFW Exploring Airport Station to downtown; from there they will Popular Destinations go through Deep Ellum and end at Fair Park Station. Check out schedules at DART.org. DART DFW Airport Map Convention Center District. One of the largest in the nation, the Kay Bailey Hutchison (Dallas) Convention Center hosts major national and international conventions, meetings, antique and Exit to DART Station Terminal auto shows, and other events. The Omni Dallas Hotel is connected to it via sky bridge. Convention Center Station Fair Park. The largest collection of Art Deco exhibit buildings in the U.S., Fair Park is a historical treasure that plays host to the State Fair of Texas®. Other attractions include the Heart of Dallas Bowl football game and year-round museums. Fair Park Station Dallas Arts District. The Dallas Arts District is the largest arts district in the nation, spanning 68 acres and comprising Entry numerous venues of cultural as well as architectural from distinction. Pearl/Arts District Station DART Omni Dallas Hotel Station NorthPark Center. Shoppers from all over the world are drawn to NorthPark’s one-of-a-kind collection of luxury and fashion-forward retailers. -

History of Mass Transit

A NEW WAY TO CONNECT TO TRAVEL Ryan Quast Figure 1.1 A NEW WAY TO CONNECT TO TRAVEL A Design Thesis Submitted to the Department of Architecture and Landscape Architecture of North Dakota State University By Ryan Quast In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Architecture Primary Thesis Advisor Thesis Committee Chair May 2015 Fargo, North Dakota List of Tables and Figures Table of Contents Figure 1.1 Train entering COR station 1 Cover Page................................................................................................1 Taken by author Signature Page....................................................................................... ...3 Figure 1.2 Northstar commuter train 13 Table of Contents......................................................................................4 www.northstartrain.org Tables and Figures....................................................................................5 Thesis Proposal.....................................................................................10 Figure 2.1 Render of The COR 15 Thesis Abstract............................................................................11 coratramsey.com/node/23 Narrative of the Theoretical Aspect of the Thesis..................12 Figure 2.2 Development plan for COR 15 Project Typology.........................................................................13 coratramsey.com/sites/default/files/COR-Development-Plan-6.0.pdf Typological Research (Case Studies)...................................................14 -

An Assessment of the DART LRT on Taxable Property Valuations and Transit Oriented Development

An Assessment of the DART LRT on Taxable Property Valuations and Transit Oriented Development Prepared for Dallas Area Rapid Transit Prepared by Bernard L. Weinstein, Ph.D. Terry L. Clower, Ph.D. With the assistance of Frances Means Lisa G. Gage Matthew Pharr Gregory Pettibon Shekeira Gillis University of North Texas Center for Economic Development and Research September 2002 Executive Summary This report updates our previous studies of the direct and indirect economic impacts of the DART LRT system. Two specific topics are addressed in detail: 1) How has proximity to an LRT station affected taxable property values? and 2) To what degree is DART rail serving as a catalyst for transit-oriented development (TOD)? Our earlier research showed that properties near DART light rail stations recorded valuation increases about 25 percent greater than those in a control group of neighborhoods not served by DART rail between 1994 and 1998. Examining the 1997 to 2001 time period, and using a somewhat different methodology, we find that proximity to a DART station continues to exert a positive influence on property valuations. Median values of residential properties increased 32.1 percent near the DART rail stations compared to 19.5 percent in the control group areas. For office buildings, the increase was 24.7 percent for the DART properties versus 11.5 percent for the non-DART properties. However, proximity to DART rail does not appear to have a significant differential impact on retail and industrial property valuations. Visits and interviews with most suburban DART member cities, as well as several non-DART cities, revealed a keen interest in transit-oriented development, with the LRT serving as the centerpiece in many instances. -

System Map 551 829 HOPKINS R DFW AIRPORT STATION @ 500 LEWISVILLE 987

LAKE LEWISVILLE 346 348 EXCHANGE PKWY 348 LEGACY DR PARKWOOD SH 121 SHOPS AT 452 348 452 LEGACY 346346 LEGACY DR TENNYSON 347 P 183 451 208 NORTH PLANO NORTHWEST PLANO DART ON-CALL ZONE PARK AND RIDE 183, 208, 346, 347, PRESTON RD 348, 451, 452 SPRING CREEK PKWY 452 SPRING CREEK PKWY 829 LAKESIDE US-75 N. CENTRAL EXPWY. COLLIN COUNTY MARKET COMMUNITY 350 COLLEGE JUPITER RD 350 TEXAS HEALTH 451 PLANO RD PRESBYTERIAN HOSPITAL PLANO PARKER RD 452 R RD COMMUNICATIONS 347 PARKER RD PARKER ROAD STATION PARKE 350, 410, 452 183 PRESTON RD. DART ON-CALL, TI Shuttle, Texoma Express 410 CUSTER RD SHOPS AT RD COIT PARK BLVD INDEPENDENCE PARK BLVD CREEK WILLOWBEND 410 ALMA ARBOR 531 347 PARK BLVD PARK BLVD CHEYENNE 870 451 BAYLOR MEDICAL CTR. 18TH 870 AT CARROLLTON HEBRON PLANO DOWNTOWN PLANO STATION MEDICAL CENTER 870 FLEX 208 OF PLANO 15TH 15TH OHIO 14TH IN T PARKWOOD E 350 R 13TH 870 N A PLANO PKWY TI 210 COLLIN CREEK MALL ON JACK HATCHELL TRANSIT CENTER FM 544 AL P KWY 841 210, 350, 451, 452, 841 FLEX SH-121 347 210 BAYLOR REGIONAL 870 MEDICAL CTR. K AVE 843 843 ROSEMEADE PKWY 534 841 PLANO PKWY PLANO PKWY HEBRON to Denton (operated by DCTA) 841 531 347 841 MARSH LUNA 350 410 WAL-MART 883 Fri/Sun 841841 ROUND GROVE NPIKE NORTH STAR RD TIMBERGREEN H TUR NORTH CARROLLTON/FRANKFORD STATION P S BUSH TURNPIKE STATION 333 U 883 UTD Shuttle, 841-843 FLEX PEAR RIDGE PEAR B IH-35E STEMMONS FRWY. -

Highland Park Carrollton Farmers Branch

LAKE LEWISVILLE 346 348 EXCHANGE PKWY PARKWOOD 348 LEGACY DR SH 121 SHOPS AT 452 348 452 LEGACY 346 LEGACY DR TENNYSON 347 P 183 451 NORTH PLANO 208 NORTHWEST PLANO DART ON-CALL ZONE PARK AND RIDE 183, 208, 346, 347, PRESTON RD 348, 451, 452 SPRING CREEK PKWY 452 SPRING CREEK PKWY 829 LAKESIDE US-75 N. CENTRAL EXPWY. COLLIN COUNTY MARKET COMMUNITY COLLEGE JUPITER RD 350 PRESBYTERIAN 451 PLANO RD HOSPITAL PLANO PARKER RD 452 R RD COMMUNICATIONS 347 PARKER RD PARKER ROAD STATION PARKE 350, 410, 452 183 PRESTON RD. DART ON-CALL, Ratheon Shuttle, TI Shuttle, Texoma Express 410 CUSTER RD SHOPS AT RD COIT PARK BLVD PARK BLVD CREEK WILLOWBEND INDEPENDENCE 410 ALMA ARBOR 531 347 PARK BLVD PARK BLVD CHEYENNE MEDICAL CENTER 870 OF PLANO 451 18TH BAYLOR MEDICAL 870 CTR. AT CARROLLTON HEBRON PLANO DOWNTOWN PLANO STATION MEDICAL CENTER 870 FLEX OF PLANO 15TH 208 15TH OHIO 14TH IN T PARKWOOD E 870 R 350 13TH 870 N A PLANO PKWY TI 210 ON JACK HATCHELL TRANSIT CENTER COLLIN CREEK MALL FM 544 AL P KWY 841 210, 350, 451, 452, 841 FLEX SH-121 347 BAYLOR REGIONAL 870 843 210 MEDICAL CTR. K AVE 843 841 ROSEMEADE PKWY 534 PLANO PKWY 841 PLANO PKWY N AVE HEBRON to Denton (operated by DCTA) BAYLOR REGIONAL 841 531 347 MEDICAL CENTER MARSH LUNA 410 350 841841 ROUND GROVE PIKE NORTH STAR RD TIMBERGREEN TURN P SH BUSH TURNPIKE STATION 333 U 883 UTD Shuttle, 841-843 FLEX IH-35E STEMMONS FRWY. RIDGE PEAR R E B RENNER RD 534 ES RG 883 FRANKFORD RD FRANKFORD RD ID EO ENT G RENNER RD 824 841 534 CAMPBELL NORTH CARROLLTON/FRANKFORD STATION 534 BRECKINRIDGE 451 RICHARDSON SHILOH 841 VAIL 883 M MARY HILLCREST RD DALLAS N. -

Farmers Branch Visitors Guide

FB FB | VISITOR GUIDE VISITOR | DISCOVERFARMERSBRANCH.COM to offer. to our of one to up belly here are you While everyone. glad you are here to discover all Farmers Branch has has Branch Farmers all discover to here are you glad for something has scene restaurant burgeoning one-of-a-kind dining, and historic museums. We are are We museums. historic and dining, one-of-a-kind our barbecue, home down or Mexican traditional DFW METROPLEX DFW the charm of a small town with mom-and-pop stores, stores, mom-and-pop with town small a of charm the Fusion, Asian prefer buds taste your Whether surrounding hustle-and-bustle, Farmers Branch retains retains Branch Farmers hustle-and-bustle, surrounding IN THE OF THE THE OF THE IN one of the nation’s largest metroplexes. Despite the the Despite metroplexes. largest nation’s the of one sundown. to sunup from busy you keep to sure be will ! here you're has grown into a vibrant community in the heart of of heart the in community vibrant a into grown has ones little of energetic most the out wear to activities What started off as Dallas County’s first settlement settlement first County’s Dallas as off started What family active enough and scene, culinary thriving trails, We're so glad so We're The year-round entertainment, miles of hike-and-bike hike-and-bike of miles entertainment, year-round The watch a Dallas Stars hockey game. hockey Stars Dallas a watch the country’s largest Arts District, take in a concert or or concert a in take District, Arts largest country’s the alike. -

Station Area Farmers Branch, Texas

STATION AREA FARMERS BRANCH, TEXAS REQUEST FOR QUALIFICATIONS MUSTANG STATION RESTAURANT & RETAIL PARK SE & SW CORNERS OF BEE STREET & VALLEY VIEW LN, FARMERS BRANCH, TX The information contained herein was obtained from sources deemed reliable; [email protected] 214-960-4528 Thomas Glendenning/ / however, no guarantees, warranties or representations as to the completeness or accuracy thereof. The presentation of this real estate information is subject Landry Kemp/ [email protected] / 214-398-2546 to errors; omissions; change of price; prior sale or lease; or withdrawal without notice. REQUEST FOR INTRODUCTION QUALIFICATIONS Executive Summary & Submission Requirements STATION AREA Key Dates & Contact FARMERS BRANCH, TEXAS Vision Key Facts MARKET INFORMATION Station Area Map Station Area City Owned Property Demographics Incentives Transportation & Access City Information EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The City of Farmers Branch is soliciting developer EXECUTIVE qualifications from firms interested in providing master development services for the city owned land surrounding SUMMARY & the Station Area. This is a Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) located adjacent to the DART Green Line Transit SUBMISSION Station. The City of Farmers Branch TOD objectives are to create a larger sustainable, livable station area district REQUIREMENTS while supporting pedestrian amenities and transit ridership. A sociable place with access, walkability, and activities STATION AREA integrated into a sustainable destination development is FARMERS BRANCH, TEXAS the vision for the remaining station area land. Commercial uses at street level, upper story residences and offices, hospitality and entertainment would be a welcome addition to the existing downtown development. Approximately 9.4 acres are ready for a development partner. SUBMISSION REQUIREMENTS The proposal should be a comprehensive and accurate presentation to include experience, organizational information, company letter and vision statement on a project concept. -

Effective: October 19, 2020

LAKE LEWISVILLE CUSTER SH 121 COMMUNICATIONS EAD H QU A R T EXCHANGE PKWY E LEGACY WEST R EXCHANGE PKWY S D 208 R GOLINK FRITO LAY LEGACY DR FAR NORTH PLANO SHOPS AT 452 GOLINK 452 LEGACY SPRING CREEK SPRING TENNYSON LEGACY DR 347 P 451 208 NORTH CENTRAL PLANO/ NORTHWEST PLANO PARK AND RIDE CHASE OAKS OHIO 208, 347, 451, 452, PRESTON RD GOLINK SPRING CREEK PKWY 452 SH 121 SPRING CREEK PKWY LAKESIDE US-75 N. CENTRAL EXPWY. COLLIN COUNTY MARKET COMMUNITY 350 COLLEGE JUPITER RD 350 E K V A TEXAS HEALTH 451 PRESBYTERIAN 452 SU HOSPITAL PLANO PARKER RD 452 COMMUNICATIONS 347 ARKER RD PARKER RD PARKER ROAD STATION P 350, 410, 452, PRESTON RD. 410 350 CUSTER RD SHOPS AT RD COIT PARK BLVD CREEK INDEPENDENCE PARK BLVD WILLOWBEND ALMA 410 ARBOR 350 531 347 PARK BLVD PARK BLVD CHEYENNE 870 HEBRON 451 18TH BAYLOR MEDICAL CTR. DOWNTOWN PLANO 870 AT CARROLLTON PLANO MEDICAL CENTER STATION 870 208 OF PLANO 15TH OHIO 15TH 14TH IN COLLIN T PARKWOOD E 350 R CREEK MALL 870 N A PLANO PKWY 208 TI ON JACK HATCHELL TRANSIT CENTER 13TH FM 544 AL P KWY 841 208, 350, 451, 452 Sunday, 841 347 350 208 BAYLOR REGIONAL 870 MEDICAL CTR. K AVE 843 843 ROSEMEADE PKWY 534 841 PLANO PKWY HEBRON 841 PLANO PKWY 531 347 841 SH-121 MARSH LUNA 350 410 883 Fri/Sun IKE 841 ROUND GROVE WALMART URNP NOR TIMBERGREEN H T S 883 CITYLINE/BUSH STATION TH NORTH CARROLLTON/FRANKFORD STATION P U STAR RD 333 R B 883 East & Express UTD Shuttle, 841, 843 IH-35E STEMMONS FRWY. -

Get a Ride Guide 2021 1

Get a Ride Guide For people with disabilities & older adults living in Dallas County For personalized help call My Ride: (972) 855-8084 January 2021 Table of Contents Section Page Introduction…………………...…… 1 About this Guide………………..… 2 Tips: Find the Right Ride……....… 4 Public Transit…………………..…. 6 Specialized Transportation…..….. 15 Medical Transport Only……..…… 23 Transportation Businesses…….... 26 Smartphone-Based Businesses… 38 Mobility as a Service……………... 39 Vanpool……….…………………… 40 Accessible Van Rentals……..…... 41 Driver Safety……….…..…………. 42 Information and Referral……..….. 43 City Index………………………….. 44 Index…………………….…………. 50 Acknowledgements…………..…... Back cover Introduction Getting around town can be a challenge for people who do not drive, especially for individuals with disabilities and older adults. From buses, vans and taxis to volunteer driver programs, the greater Dallas area has options. But sometimes finding transportation that meets your specific needs can be confusing. Providers have different service areas, hours of operation, eligibility requirements, etc. This guide was created to help you understand the transportation options in Dallas County.* Use this guide to find the right ride for you or someone you know. If you would like your organization to be included in the guide, please submit a written request to: My Ride Dallas Email: [email protected] Tel: (972) 855-8084 Website: www.myridedallas.org Community Council of Greater Dallas 1341 W Mockingbird Lane, Suite 1000W Dallas, TX 75247 *For transportation options in other counties: NCTCOG Regional Transit Providers List www.nctcog.org/trans/plan/transit/transit-providers My Ride Tarrant www.facebook.com/MyRIDETarrant/ 682-587-7099 [email protected] Get a Ride Guide 2021 1 About This Guide This guide was created by My Ride Dallas, a collaboration of 90 organizations led by the Community Council of Greater Dallas and the Dallas Area Agency on Aging.