Mount Olympus National Monument

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mount Olympus, Part I

MMountount Olympus,Olympus, PPartart I 2 Lesson Objectives Core Content Objectives Students will: Explain that the ancient Greeks worshipped many gods and goddesses Identify Mount Olympus as the place the ancient Greeks believed was the home of the gods Language Arts Objectives The following language arts objectives are addressed in this lesson. Objectives aligning with the Common Core State Standards are noted with the corresponding standard in parentheses. Refer to the Alignment Chart for additional standards addressed in all lessons in this domain. Students will: Recount the story of the Olympian gods and goddesses from “Mount Olympus, Part I,” using transition words like fi rst, next, then, and fi nally, and discuss with one or more peers (RL.2.2) Identify the three seas that surrounded ancient Greece using a map of ancient Greece as a guide (RI.2.7) With assistance, categorize and organize facts and information on the ancient Greek civilization (W.2.8) Summarize orally the information contained in “Mount Olympus, Part I” (SL.2.2) Prior to listening to “Mount Olympus, Part I,” identify orally what they know and have learned about the ancient Greek civilization Prior to listening to “Mount Olympus, Part I,” orally predict powers or skills that the gods and goddesses were believed to have and then compare the actual outcome to the prediction The Ancient Greek Civilization 2 | Mount Olympus, Part I 23 © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation Core Vocabulary delightfully, adv. With great delight or pleasure Example: Jane delightfully helped her mother cook their favorite meal, homemade macaroni and cheese. Variation(s): none longingly, adv. -

Climbing the Sea Annual Report

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG MARCH/APRIL 2015 • VOLUME 109 • NO. 2 MountaineerEXPLORE • LEARN • CONSERVE Annual Report 2014 PAGE 3 Climbing the Sea sailing PAGE 23 tableofcontents Mar/Apr 2015 » Volume 109 » Number 2 The Mountaineers enriches lives and communities by helping people explore, conserve, learn about and enjoy the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest and beyond. Features 3 Breakthrough The Mountaineers Annual Report 2014 23 Climbing the Sea a sailing experience 28 Sea Kayaking 23 a sport for everyone 30 National Trails Day celebrating the trails we love Columns 22 SUMMIT Savvy Guess that peak 29 MEMbER HIGHLIGHT Masako Nair 32 Nature’S WAy Western Bluebirds 34 RETRO REWIND Fred Beckey 36 PEAK FITNESS 30 Back-to-Backs Discover The Mountaineers Mountaineer magazine would like to thank The Mountaineers If you are thinking of joining — or have joined and aren’t sure where Foundation for its financial assistance. The Foundation operates to start — why not set a date to Meet The Mountaineers? Check the as a separate organization from The Mountaineers, which has received about one-third of the Foundation’s gifts to various Branching Out section of the magazine for times and locations of nonprofit organizations. informational meetings at each of our seven branches. Mountaineer uses: CLEAR on the cover: Lori Stamper learning to sail. Sailing story on page 23. photographer: Alan Vogt AREA 2 the mountaineer magazine mar/apr 2015 THE MOUNTAINEERS ANNUAL REPORT 2014 FROM THE BOARD PRESIDENT Without individuals who appreciate the natural world and actively champion its preservation, we wouldn’t have the nearly 110 million acres of wilderness areas that we enjoy today. -

Orpheus in the Underworld

Orpheus in the Underworld Music by Jacques Offenbach, French Libretto by Cremieux & Halevy English adaptation by Snoo Wilson & David Pountney THE CAST Orpheus (a musician) ...................................................................... Mikal J. Kraklio Eurydice (his wife) .......................................................................... Jen Christianson Ann Michels (April 1 & 9) Aristaeus / Pluto (a shepherd / the god of the underworld) ............. James Hamilton Public Opinion (guardian of morals) .................................................... Lynne Hicks Jupiter (King of the gods) ......................................................... Waldyn J. Benbenek Juno (his wife) ................................................................................... Judith McClain Venus .................................................................................................... Ann Michels Emily Coates (April 1 & 9) Cupid................................................................................................. Sara Gustafson Diana .............................................................................................. Alyssa K. Lingor Mars ..........................................................................................Christopher Michela Mercury ................................................................................................ Todd Coulter Dr. Morpheus (demi-god of sleep) .................................................... Richard Rames Rhadamanthys (one of the Triple Judges -

The Twelve Gods of Mount Olympus

TThehe TTwelvewelve GGodsods ooff MountMount OlympusOlympus 1 Lesson Objectives Core Content Objectives Students will: Explain that the ancient Greeks worshipped many gods and goddesses Explain that the gods and goddesses of ancient Greece were believed to be immortal and to have supernatural powers, unlike humans Identify the Greek gods and goddesses in this read-aloud Identify Mount Olympus as the place believed by the ancient Greeks to be the home of the gods Identify Greek myths as a type of f ction Language Arts Objectives The following language arts objectives are addressed in this lesson. Objectives aligning with the Common Core State Standards are noted with the corresponding standard in parentheses. Refer to the Alignment Chart for additional standards addressed in all lessons in this domain. Students will: Orally compare and contrast Greek gods and humans (RL.2.9) Interpret information pertaining to Greece from a world map or globe and connect it to information learned in “The Twelve Gods of Mount Olympus” (RI.2.7) Add drawings to descriptions of the Greek god Zeus to clarify ideas, thoughts, and feelings (SL.2.5) Share writing with others Identify how Leonidas feels about going to Olympia to see the races held in honor of Zeus Greek Myths: Supplemental Guide 1 | The Twelve Gods of Mount Olympus 13 © 2013 Core Knowledge Foundation Core Vocabulary glimpse, n. A brief or quick look Example: Jan snuck into the kitchen before the party to get a glimpse of her birthday cake. Variation(s): glimpses sanctuary, n. A holy place; a safe, protected place Example: Cyrus went to the sanctuary to pray to the gods. -

1922 Elizabeth T

co.rYRIG HT, 192' The Moootainetro !scot1oror,d The MOUNTAINEER VOLUME FIFTEEN Number One D EC E M BER 15, 1 9 2 2 ffiount Adams, ffiount St. Helens and the (!oat Rocks I ncoq)Ora,tecl 1913 Organized 190!i EDITORlAL ST AitF 1922 Elizabeth T. Kirk,vood, Eclttor Margaret W. Hazard, Associate Editor· Fairman B. L�e, Publication Manager Arthur L. Loveless Effie L. Chapman Subsc1·iption Price. $2.00 per year. Annual ·(onl�') Se,·ent�·-Five Cents. Published by The Mountaineers lncorJ,orated Seattle, Washington Enlerecl as second-class matter December 15, 19t0. at the Post Office . at . eattle, "\Yash., under the .-\0t of March 3. 1879. .... I MOUNT ADAMS lllobcl Furrs AND REFLEC'rION POOL .. <§rtttings from Aristibes (. Jhoutribes Author of "ll3ith the <6obs on lltount ®l!!mµus" �. • � J� �·,,. ., .. e,..:,L....._d.L.. F_,,,.... cL.. ��-_, _..__ f.. pt",- 1-� r�._ '-';a_ ..ll.-�· t'� 1- tt.. �ti.. ..._.._....L- -.L.--e-- a';. ��c..L. 41- �. C4v(, � � �·,,-- �JL.,�f w/U. J/,--«---fi:( -A- -tr·�� �, : 'JJ! -, Y .,..._, e� .,...,____,� � � t-..__., ,..._ -u..,·,- .,..,_, ;-:.. � --r J /-e,-i L,J i-.,( '"'; 1..........,.- e..r- ,';z__ /-t.-.--,r� ;.,-.,.....__ � � ..-...,.,-<. ,.,.f--· :tL. ��- ''F.....- ,',L � .,.__ � 'f- f-� --"- ��7 � �. � �;')'... f ><- -a.c__ c/ � r v-f'.fl,'7'71.. I /!,,-e..-,K-// ,l...,"4/YL... t:l,._ c.J.� J..,_-...A 'f ',y-r/� �- lL.. ��•-/IC,/ ,V l j I '/ ;· , CONTENTS i Page Greetings .......................................................................tlristicles }!}, Phoiitricles ........ r The Mount Adams, Mount St. Helens, and the Goat Rocks Outing .......................................... B1/.ith Page Bennett 9 1 Selected References from Preceding Mount Adams and Mount St. -

Geologic Map of the Simcoe Mountains Volcanic Field, Main Central Segment, Yakama Nation, Washington by Wes Hildreth and Judy Fierstein

Prepared in Cooperation with the Water Resources Program of the Yakama Nation Geologic Map of the Simcoe Mountains Volcanic Field, Main Central Segment, Yakama Nation, Washington By Wes Hildreth and Judy Fierstein Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3315 Photograph showing Mount Adams andesitic stratovolcano and Signal Peak mafic shield volcano viewed westward from near Mill Creek Guard Station. Low-relief rocky meadows and modest forested ridges marked by scattered cinder cones and shields are common landforms in Simcoe Mountains volcanic field. Mount Adams (elevation: 12,276 ft; 3,742 m) is centered 50 km west and 2.8 km higher than foreground meadow (elevation: 2,950 ft.; 900 m); its eruptions began ~520 ka, its upper cone was built in late Pleistocene, and several eruptions have taken place in the Holocene. Signal Peak (elevation: 5,100 ft; 1,555 m), 20 km west of camera, is one of largest and highest eruptive centers in Simcoe Mountains volcanic field; short-lived shield, built around 3.7 Ma, is seven times older than Mount Adams. 2015 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Contents Introductory Overview for Non-Geologists ...............................................................................................1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................2 Physiography, Environment, Boundary Surveys, and Access ......................................................6 Previous Geologic -

A Decision Framework for Managing the Spirit Lake and Toutle River System at Mount St

THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS This PDF is available at http://nap.edu/24874 SHARE A Decision Framework for Managing the Spirit Lake and Toutle River System at Mount St. Helens (2018) DETAILS 336 pages | 6 x 9 | PAPERBACK ISBN 978-0-309-46444-4 | DOI 10.17226/24874 CONTRIBUTORS GET THIS BOOK Committee on Long-Term Management of the Spirit Lake/Toutle River System in Southwest Washington; Committee on Geological and Geotechnical Engineering; Board on Earth Sciences and Resources; Water Science and Technology Board; Division on Earth and Life Studies; Board on Environmental Change and Society; FIND RELATED TITLES Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine SUGGESTED CITATION National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2018. A Decision Framework for Managing the Spirit Lake and Toutle River System at Mount St. Helens. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24874. Visit the National Academies Press at NAP.edu and login or register to get: – Access to free PDF downloads of thousands of scientific reports – 10% off the price of print titles – Email or social media notifications of new titles related to your interests – Special offers and discounts Distribution, posting, or copying of this PDF is strictly prohibited without written permission of the National Academies Press. (Request Permission) Unless otherwise indicated, all materials in this PDF are copyrighted by the National Academy of Sciences. Copyright © National Academy -

2018 Basic Alpine Climbing Course Student Handbook

Mountaineers Basic Alpine Climbing Course 2018 Student Handbook 2018 Basic Alpine Climbing Course Student Handbook Allison Swanson [Basic Course Chair] Cebe Wallace [Meet and Greet, Reunion] Diane Gaddis [SIG Organization] Glenn Eades [Graduation] Jan Abendroth [Field Trips] Jeneca Bowe [Lectures] Jared Bowe [Student Tracking] Jim Nelson [Alpine Fashionista, North Cascades Connoisseur] Liana Robertshaw [Basic Climbs] Vineeth Madhusudanan [Enrollment] Fred Beckey, photograph in High Adventure, by Ira Spring, 1951 In loving memory Fred Page Beckey 1 [January 14, 1923 – October 30, 2017] Mountaineers Basic Alpine Climbing Course 2018 Student Handbook 2018 BASIC ALPINE CLIMBING COURSE STUDENT HANDBOOK COURSE OVERVIEW ........................................................................................................................ 3 Class Meetings ............................................................................................................................ 3 Field Trips ................................................................................................................................... 4 Small Instructional Group (SIG) ................................................................................................. 5 Skills Practice Nights .................................................................................................................. 5 References ................................................................................................................................... 6 Three additional -

Geologic History of Siletzia, a Large Igneous Province in the Oregon And

Geologic history of Siletzia, a large igneous province in the Oregon and Washington Coast Range: Correlation to the geomagnetic polarity time scale and implications for a long-lived Yellowstone hotspot Wells, R., Bukry, D., Friedman, R., Pyle, D., Duncan, R., Haeussler, P., & Wooden, J. (2014). Geologic history of Siletzia, a large igneous province in the Oregon and Washington Coast Range: Correlation to the geomagnetic polarity time scale and implications for a long-lived Yellowstone hotspot. Geosphere, 10 (4), 692-719. doi:10.1130/GES01018.1 10.1130/GES01018.1 Geological Society of America Version of Record http://cdss.library.oregonstate.edu/sa-termsofuse Downloaded from geosphere.gsapubs.org on September 10, 2014 Geologic history of Siletzia, a large igneous province in the Oregon and Washington Coast Range: Correlation to the geomagnetic polarity time scale and implications for a long-lived Yellowstone hotspot Ray Wells1, David Bukry1, Richard Friedman2, Doug Pyle3, Robert Duncan4, Peter Haeussler5, and Joe Wooden6 1U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefi eld Road, Menlo Park, California 94025-3561, USA 2Pacifi c Centre for Isotopic and Geochemical Research, Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, 6339 Stores Road, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, Canada 3Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Hawaii at Manoa, 1680 East West Road, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822, USA 4College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, 104 CEOAS Administration Building, Corvallis, Oregon 97331-5503, USA 5U.S. Geological Survey, 4210 University Drive, Anchorage, Alaska 99508-4626, USA 6School of Earth Sciences, Stanford University, 397 Panama Mall Mitchell Building 101, Stanford, California 94305-2210, USA ABSTRACT frames, the Yellowstone hotspot (YHS) is on southern Vancouver Island (Canada) to Rose- or near an inferred northeast-striking Kula- burg, Oregon (Fig. -

New Titles for Spring 2021 Green Trails Maps Spring

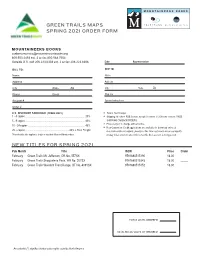

GREEN TRAILS MAPS SPRING 2021 ORDER FORM recreation • lifestyle • conservation MOUNTAINEERS BOOKS [email protected] 800.553.4453 ext. 2 or fax 800.568.7604 Outside U.S. call 206.223.6303 ext. 2 or fax 206.223.6306 Date: Representative: BILL TO: SHIP TO: Name Name Address Address City State Zip City State Zip Phone Email Ship Via Account # Special Instructions Order # U.S. DISCOUNT SCHEDULE (TRADE ONLY) ■ Terms: Net 30 days. 1 - 4 copies ........................................................................................ 20% ■ Shipping: All others FOB Seattle, except for orders of 25 books or more. FREE 5 - 9 copies ........................................................................................ 40% SHIPPING ON BACKORDERS. ■ Prices subject to change without notice. 10 - 24 copies .................................................................................... 45% ■ New Customers: Credit applications are available for download online at 25 + copies ................................................................45% + Free Freight mountaineersbooks.org/mtn_newstore.cfm. New customers are encouraged to This schedule also applies to single or assorted titles and library orders. prepay initial orders to speed delivery while their account is being set up. NEW TITLES FOR SPRING 2021 Pub Month Title ISBN Price Order February Green Trails Mt. Jefferson, OR No. 557SX 9781680515190 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass, WA No. 207SX 9781680515343 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Wasatch Front Range, UT No. 4091SX 9781680515152 18.00 _____ TOTAL UNITS ORDERED TOTAL RETAIL VALUE OF ORDERED An asterisk (*) signifies limited sales rights outside North America. QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE WASHINGTON ____ 9781680513448 Alpine Lakes East Stuart Range, WA No. 208SX $18.00 ____ 9781680514537 Old Scab Mountain, WA No. 272 $8.00 ____ ____ 9781680513455 Alpine Lakes West Stevens Pass, WA No. -

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities

Curt Teich Postcard Archives Towns and Cities Alaska Aialik Bay Alaska Highway Alcan Highway Anchorage Arctic Auk Lake Cape Prince of Wales Castle Rock Chilkoot Pass Columbia Glacier Cook Inlet Copper River Cordova Curry Dawson Denali Denali National Park Eagle Fairbanks Five Finger Rapids Gastineau Channel Glacier Bay Glenn Highway Haines Harding Gateway Homer Hoonah Hurricane Gulch Inland Passage Inside Passage Isabel Pass Juneau Katmai National Monument Kenai Kenai Lake Kenai Peninsula Kenai River Kechikan Ketchikan Creek Kodiak Kodiak Island Kotzebue Lake Atlin Lake Bennett Latouche Lynn Canal Matanuska Valley McKinley Park Mendenhall Glacier Miles Canyon Montgomery Mount Blackburn Mount Dewey Mount McKinley Mount McKinley Park Mount O’Neal Mount Sanford Muir Glacier Nome North Slope Noyes Island Nushagak Opelika Palmer Petersburg Pribilof Island Resurrection Bay Richardson Highway Rocy Point St. Michael Sawtooth Mountain Sentinal Island Seward Sitka Sitka National Park Skagway Southeastern Alaska Stikine Rier Sulzer Summit Swift Current Taku Glacier Taku Inlet Taku Lodge Tanana Tanana River Tok Tunnel Mountain Valdez White Pass Whitehorse Wrangell Wrangell Narrow Yukon Yukon River General Views—no specific location Alabama Albany Albertville Alexander City Andalusia Anniston Ashford Athens Attalla Auburn Batesville Bessemer Birmingham Blue Lake Blue Springs Boaz Bobler’s Creek Boyles Brewton Bridgeport Camden Camp Hill Camp Rucker Carbon Hill Castleberry Centerville Centre Chapman Chattahoochee Valley Cheaha State Park Choctaw County -

1967, Al and Frances Randall and Ramona Hammerly

The Mountaineer I L � I The Mountaineer 1968 Cover photo: Mt. Baker from Table Mt. Bob and Ira Spring Entered as second-class matter, April 8, 1922, at Post Office, Seattle, Wash., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly and semi-monthly during March and April by The Mountaineers, P.O. Box 122, Seattle, Washington, 98111. Clubroom is at 719Y2 Pike Street, Seattle. Subscription price monthly Bulletin and Annual, $5.00 per year. The Mountaineers To explore and study the mountains, forests, and watercourses of the Northwest; To gather into permanent form the history and traditions of this region; To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise the natural beauty of North west America; To make expeditions into these regions m fulfill ment of the above purposes; To encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all lovers of outdoor life. EDITORIAL STAFF Betty Manning, Editor, Geraldine Chybinski, Margaret Fickeisen, Kay Oelhizer, Alice Thorn Material and photographs should be submitted to The Mountaineers, P.O. Box 122, Seattle, Washington 98111, before November 1, 1968, for consideration. Photographs must be 5x7 glossy prints, bearing caption and photographer's name on back. The Mountaineer Climbing Code A climbing party of three is the minimum, unless adequate support is available who have knowledge that the climb is in progress. On crevassed glaciers, two rope teams are recommended. Carry at all times the clothing, food and equipment necessary. Rope up on all exposed places and for all glacier travel. Keep the party together, and obey the leader or majority rule. Never climb beyond your ability and knowledge.