Blast-Zone Hiking Raptor Viewing Wild Streaking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Play Fairway Analysis of the Central Cascades Arc-Backarc Regime, Oregon: Preliminary Indications

GRC Transactions, Vol. 39, 2015 Play Fairway Analysis of the Central Cascades Arc-Backarc Regime, Oregon: Preliminary Indications Philip E. Wannamaker1, Andrew J. Meigs2, B. Mack Kennedy3, Joseph N. Moore1, Eric L. Sonnenthal3, Virginie Maris1, and John D. Trimble2 1University of Utah/EGI, Salt Lake City UT 2Oregon State University, College of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, Corvallis OR 3Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Center for Isotope Geochemistry, Berkeley CA [email protected] Keywords Play Fairway Analysis, geothermal exploration, Cascades, andesitic volcanism, rift volcanism, magnetotellurics, LiDAR, geothermometry ABSTRACT We are assessing the geothermal potential including possible blind systems of the Central Cascades arc-backarc regime of central Oregon through a Play Fairway Analysis (PFA) of existing geoscientific data. A PFA working model is adopted where MT low resistivity upwellings suggesting geothermal fluids may coincide with dilatent geological structural settings and observed thermal fluids with deep high-temperature contributions. A challenge in the Central Cascades region is to make useful Play assessments in the face of sparse data coverage. Magnetotelluric (MT) data from the relatively dense EMSLAB transect combined with regional Earthscope stations have undergone 3D inversion using a new edge finite element formulation. Inversion shows that low resistivity upwellings are associated with known geothermal areas Breitenbush and Kahneeta Hot Springs in the Mount Jefferson area, as well as others with no surface manifestations. At Earthscope sampling scales, several low-resistivity lineaments in the deep crust project from the east to the Cascades, most prominently perhaps beneath Three Sisters. Structural geology analysis facilitated by growing LiDAR coverage is revealing numerous new faults confirming that seemingly regional NW-SE fault trends intersect N-S, Cascades graben- related faults in areas of known hot springs including Breitenbush. -

Land Areas of the National Forest System, As of September 30, 2019

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2019 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2019 Metric Equivalents When you know: Multiply by: To fnd: Inches (in) 2.54 Centimeters Feet (ft) 0.305 Meters Miles (mi) 1.609 Kilometers Acres (ac) 0.405 Hectares Square feet (ft2) 0.0929 Square meters Yards (yd) 0.914 Meters Square miles (mi2) 2.59 Square kilometers Pounds (lb) 0.454 Kilograms United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2019 As of September 30, 2019 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, DC 20250-0003 Website: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover Photo: Mt. Hood, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon Courtesy of: Susan Ruzicka USDA Forest Service WO Lands and Realty Management Statistics are current as of: 10/17/2019 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,994,068 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 503 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 149 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 456 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The Forest Service also administers several other types of nationally designated -

1922 Elizabeth T

co.rYRIG HT, 192' The Moootainetro !scot1oror,d The MOUNTAINEER VOLUME FIFTEEN Number One D EC E M BER 15, 1 9 2 2 ffiount Adams, ffiount St. Helens and the (!oat Rocks I ncoq)Ora,tecl 1913 Organized 190!i EDITORlAL ST AitF 1922 Elizabeth T. Kirk,vood, Eclttor Margaret W. Hazard, Associate Editor· Fairman B. L�e, Publication Manager Arthur L. Loveless Effie L. Chapman Subsc1·iption Price. $2.00 per year. Annual ·(onl�') Se,·ent�·-Five Cents. Published by The Mountaineers lncorJ,orated Seattle, Washington Enlerecl as second-class matter December 15, 19t0. at the Post Office . at . eattle, "\Yash., under the .-\0t of March 3. 1879. .... I MOUNT ADAMS lllobcl Furrs AND REFLEC'rION POOL .. <§rtttings from Aristibes (. Jhoutribes Author of "ll3ith the <6obs on lltount ®l!!mµus" �. • � J� �·,,. ., .. e,..:,L....._d.L.. F_,,,.... cL.. ��-_, _..__ f.. pt",- 1-� r�._ '-';a_ ..ll.-�· t'� 1- tt.. �ti.. ..._.._....L- -.L.--e-- a';. ��c..L. 41- �. C4v(, � � �·,,-- �JL.,�f w/U. J/,--«---fi:( -A- -tr·�� �, : 'JJ! -, Y .,..._, e� .,...,____,� � � t-..__., ,..._ -u..,·,- .,..,_, ;-:.. � --r J /-e,-i L,J i-.,( '"'; 1..........,.- e..r- ,';z__ /-t.-.--,r� ;.,-.,.....__ � � ..-...,.,-<. ,.,.f--· :tL. ��- ''F.....- ,',L � .,.__ � 'f- f-� --"- ��7 � �. � �;')'... f ><- -a.c__ c/ � r v-f'.fl,'7'71.. I /!,,-e..-,K-// ,l...,"4/YL... t:l,._ c.J.� J..,_-...A 'f ',y-r/� �- lL.. ��•-/IC,/ ,V l j I '/ ;· , CONTENTS i Page Greetings .......................................................................tlristicles }!}, Phoiitricles ........ r The Mount Adams, Mount St. Helens, and the Goat Rocks Outing .......................................... B1/.ith Page Bennett 9 1 Selected References from Preceding Mount Adams and Mount St. -

Geologic Map of the Simcoe Mountains Volcanic Field, Main Central Segment, Yakama Nation, Washington by Wes Hildreth and Judy Fierstein

Prepared in Cooperation with the Water Resources Program of the Yakama Nation Geologic Map of the Simcoe Mountains Volcanic Field, Main Central Segment, Yakama Nation, Washington By Wes Hildreth and Judy Fierstein Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3315 Photograph showing Mount Adams andesitic stratovolcano and Signal Peak mafic shield volcano viewed westward from near Mill Creek Guard Station. Low-relief rocky meadows and modest forested ridges marked by scattered cinder cones and shields are common landforms in Simcoe Mountains volcanic field. Mount Adams (elevation: 12,276 ft; 3,742 m) is centered 50 km west and 2.8 km higher than foreground meadow (elevation: 2,950 ft.; 900 m); its eruptions began ~520 ka, its upper cone was built in late Pleistocene, and several eruptions have taken place in the Holocene. Signal Peak (elevation: 5,100 ft; 1,555 m), 20 km west of camera, is one of largest and highest eruptive centers in Simcoe Mountains volcanic field; short-lived shield, built around 3.7 Ma, is seven times older than Mount Adams. 2015 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Contents Introductory Overview for Non-Geologists ...............................................................................................1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................2 Physiography, Environment, Boundary Surveys, and Access ......................................................6 Previous Geologic -

Research Natural Areas on National Forest System Lands in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Utah, and Western Wyoming: a Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and Educators

USDA United States Department of Agriculture Research Natural Areas on Forest Service National Forest System Lands Rocky Mountain Research Station in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, General Technical Report RMRS-CTR-69 Utah, and Western Wyoming: February 2001 A Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and E'ducators Angela G. Evenden Melinda Moeur J. Stephen Shelly Shannon F. Kimball Charles A. Wellner Abstract Evenden, Angela G.; Moeur, Melinda; Shelly, J. Stephen; Kimball, Shannon F.; Wellner, Charles A. 2001. Research Natural Areas on National Forest System Lands in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Utah, and Western Wyoming: A Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and Educators. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-69. Ogden, UT: U.S. Departmentof Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 84 p. This guidebook is intended to familiarize land resource managers, scientists, educators, and others with Research Natural Areas (RNAs) managed by the USDA Forest Service in the Northern Rocky Mountains and lntermountain West. This guidebook facilitates broader recognitionand use of these valuable natural areas by describing the RNA network, past and current research and monitoring, management, and how to use RNAs. About The Authors Angela G. Evenden is biological inventory and monitoring project leader with the National Park Service -NorthernColorado Plateau Network in Moab, UT. She was formerly the Natural Areas Program Manager for the Rocky Mountain Research Station, Northern Region and lntermountain Region of the USDA Forest Service. Melinda Moeur is Research Forester with the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain ResearchStation in Moscow, ID, and one of four Research Natural Areas Coordinators from the Rocky Mountain Research Station. J. Stephen Shelly is Regional Botanist and Research Natural Areas Coordinator with the USDA Forest Service, Northern Region Headquarters Office in Missoula, MT. -

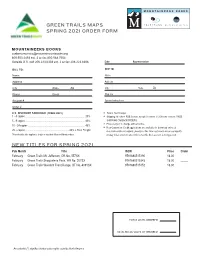

New Titles for Spring 2021 Green Trails Maps Spring

GREEN TRAILS MAPS SPRING 2021 ORDER FORM recreation • lifestyle • conservation MOUNTAINEERS BOOKS [email protected] 800.553.4453 ext. 2 or fax 800.568.7604 Outside U.S. call 206.223.6303 ext. 2 or fax 206.223.6306 Date: Representative: BILL TO: SHIP TO: Name Name Address Address City State Zip City State Zip Phone Email Ship Via Account # Special Instructions Order # U.S. DISCOUNT SCHEDULE (TRADE ONLY) ■ Terms: Net 30 days. 1 - 4 copies ........................................................................................ 20% ■ Shipping: All others FOB Seattle, except for orders of 25 books or more. FREE 5 - 9 copies ........................................................................................ 40% SHIPPING ON BACKORDERS. ■ Prices subject to change without notice. 10 - 24 copies .................................................................................... 45% ■ New Customers: Credit applications are available for download online at 25 + copies ................................................................45% + Free Freight mountaineersbooks.org/mtn_newstore.cfm. New customers are encouraged to This schedule also applies to single or assorted titles and library orders. prepay initial orders to speed delivery while their account is being set up. NEW TITLES FOR SPRING 2021 Pub Month Title ISBN Price Order February Green Trails Mt. Jefferson, OR No. 557SX 9781680515190 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Snoqualmie Pass, WA No. 207SX 9781680515343 18.00 _____ February Green Trails Wasatch Front Range, UT No. 4091SX 9781680515152 18.00 _____ TOTAL UNITS ORDERED TOTAL RETAIL VALUE OF ORDERED An asterisk (*) signifies limited sales rights outside North America. QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE QTY. CODE TITLE PRICE CASE WASHINGTON ____ 9781680513448 Alpine Lakes East Stuart Range, WA No. 208SX $18.00 ____ 9781680514537 Old Scab Mountain, WA No. 272 $8.00 ____ ____ 9781680513455 Alpine Lakes West Stevens Pass, WA No. -

Triangulation in Utah 1871-1934

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director Bulletin 913 TRIANGULATION IN UTAH 1871-1934 J. G. STAACK Chief Topographic Engineer UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1940 Tor sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 20 cents (paper) CONTENTS Page Introduction ______________________________________________________ 1 Scope of report------__-_-_---_----_------------ --__---__ _ 1 Precision __ _ ________________________ _ __________________ _ ___ 1 Instruments used._ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 2 Station marks___- _ _.__ __ __ _ 2 Datum_-_-_-__ __________________________ ______ ______-___.__ 3 Methods of readjustment..._____.-.__..________.___._._...___.__ 4 Form of results__-.________________________ _.___-_____.______ 5 Arrangement__.______________________________ _ ___ _ ________ 6 Descriptions of stations._______________________________________ 6 Azimuths and distances.__ ____-_.._---_--_________ -____ __ __ ^ 7 Maps.__----__-----_-_---__-_--_-___-_-___-__-__-_-_-___.-.__ 7 Personnel_ _ __-----_-_-_---_---------_--__-____-__-_.--_.___ . 7 Projects 9 Uinta Forest Reserve, 1897-98_ 9 Cottonwood and Park City special quadrangles, 1903____ _ 19 Iron Springs special quadrangle, 1905____________________________ 22 Northeastern Utah, 1909.. -_. 26 Eastern Utah, 1910 - . 30 Logan quadrangle, 1913._________-__-__'_--______-___:_____.____ 42 Uintah County, 1913___-__. 48 Eastern Utah, 1914.. ... _ _ .. 55 Northern Utah, 1915 (Hodgeson)_____-___ __-___-_-_-__-_--. _. 58 Northern Utah, 1915 <Urquhart)_. -

OREGON GEOLOGY Published by the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries

OREGON GEOLOGY published by the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries VOLUME 47. NUMBER 10 OCTOBER 1985 •-_Q OREGON GEOLOGY OIL AND GAS NEWS (ISSN 0164-3304) VOLUME 47, NUMBER 10 OCTOBER 1985 Columbia County Exxon Corporation spudded its GPE Federal Com. I on Published monthly by the Oregon Department of Geology and Min September I. The well name is a change from GPE Federal 2, eraI Industries (Volumes 1 through 40 were entitled The Ore Bin). permitted for section 3. T. 4 N .. R. 3 W. Proposed total depth is 12.000 ft. The contractor is Peter Bawden. Governing Board Donald A. Haagensen, Chairman ............. Portland Coos County Allen P. Stinchfield .................... North Bend Amoco Production Company is drilling ahead on Weyer Sidney R. Johnson. .. Baker haeuser "F" I in section 10, T. 25 S .. R. 10 W. The well has a projected total depth of 5,900 ft and is being drilled by Taylor State Geologist ..................... Donald A. Hull Drilling. Deputy State Geologist. .. John D. Beaulieu Publications Manager/Editor ............. Beverly F. Vogt Lane County Leavitt's Exploration and Drilling Co. has drilled Merle I to Associate Editor . Klaus K.E. Neuendorf a total depth of 2,870 ft and plugged the well as a dry hole. The well. in section 25. T. 16 S .. R. 5 W .. was drilled 2 mi southeast of Main Office: 910 State Office Building, 1400 SW Fifth Ave nue. Portland 9720 I, phone (503) 229-5580. Ty Settles' Cindy I. drilled earlier this year to 1.600 ft. A.M. Jannsen Well Drilling Co. -

GEOLOGIC MAP of the MOUNT ADAMS VOLCANIC FIELD, CASCADE RANGE of SOUTHERN WASHINGTON by Wes Hildreth and Judy Fierstein

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP 1-2460 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE MOUNT ADAMS VOLCANIC FIELD, CASCADE RANGE OF SOUTHERN WASHINGTON By Wes Hildreth and Judy Fierstein When I climbed Mount Adams {17-18 August 1945] about 1950 m (6400') most of the landscape is mantled I think I found the answer to the question of why men by dense forests and huckleberry thickets. Ten radial stake everything to reach these peaks, yet obtain no glaciers and the summit icecap today cover only about visible reward for their exhaustion... Man's greatest 2.5 percent (16 km2) of the cone, but in latest Pleis experience-the one that brings supreme exultation tocene time (25-11 ka) as much as 80 percent of Mount is spiritual, not physical. It is the catching of some Adams was under ice. The volcano is drained radially vision of the universe and translating it into a poem by numerous tributaries of the Klickitat, White Salmon, or work of art ... Lewis, and Cis pus Rivers (figs. 1, 2), all of which ulti William 0. Douglas mately flow into the Columbia. Most of Mount Adams and a vast area west of it are Of Men and Mountains administered by the U.S. Forest Service, which has long had the dual charge of protecting the Wilderness Area and of providing a network of logging roads almost INTRODUCTION everywhere else. The northeast quadrant of the moun One of the dominating peaks of the Pacific North tain, however, lies within a part of the Yakima Indian west, Mount Adams, stands astride the Cascade crest, Reservation that is open solely to enrolled members of towering 3 km above the surrounding valleys. -

Mount Jefferson Wilderness

Double Olallie Peaks Lake Mount Jefferson Wilderness Boulder Monon Creek Lake Meadows Breitenbush Trailheads Mountain Ruddy Hill Overnight Use: Central Cascades Wilderness Rock Permit Required Crown Lake & BreitenbushCone Pyramid Lake Day Use: Central Cascades Wilderness Permit Roaring Creek Butte Required Campbell Butte Devils Bear Overnight Use: Central Cascades Wilderness Peak Quitters Gale Point Point Permit Required Hill South Breitenbush Dinah-mo & Crag Peak Day Use: Free Self-Issue Permit Timber Butte No Campfires Triangulation & Outerson Mountain Transportation Triangulation Peak Triangulation Park 5 - HIGH DEGREE OF USER COMFORT Peak Butte 4 -L MionOshDeaEdRATE DEGREE OF USER Sentinel COMFORT Hills Whitewater 3 - SUITABLE FOR PASSENGER CARS 2 - HIGH CLEARANCE VEHICLES Cheat Creek Pacific Crest Trail Woodpecker Trails Camp Creek Hill Woodpecker Ownership Butte Mount Bureau of Indian Affairs Jefferson U.S. Forest Service Mount Bruno Pamelia Lake Mount Jefferson Wilderness STP;B Saltdate Land Minto Mountain PrivaPtee tIenr dividual or Company Grizzly Goat Minto Peak 0 0.5 1 2 3 4 5 Mountain Peak Miles Bear The Butte Lizard CathedralTable Point Rocks Table Lake Bingham Ridge Forked North Butte Cinder Peak Jefferson Lake 22 Marion Lake Cabot South Lake Cinder Peak Pine Ridge & Abbot Marion Rockpile Butte Turpentine Marion l Mountain MountainLake i a r T t s e Marion r Turpentine C Peak Peak Bear Saddle Green c Mountain i Valley f Big Meadows Peak i c Loop Red a Butte P Duffy Butte Porcupine Duffy Lake Peak Jack Lake Three Fingered Jack Maxwell Maxwell Butte Butte Disclaimer Round Little Nash Lake This product is reproduced from information prepared by Crater Lost the USDA, Forest Service or from other suppliers. -

Summary of Public Comment, Appendix B

Summary of Public Comment on Roadless Area Conservation Appendix B Requests for Inclusion or Exemption of Specific Areas Table B-1. Requested Inclusions Under the Proposed Rulemaking. Region 1 Northern NATIONAL FOREST OR AREA STATE GRASSLAND The state of Idaho Multiple ID (Individual, Boise, ID - #6033.10200) Roadless areas in Idaho Multiple ID (Individual, Olga, WA - #16638.10110) Inventoried and uninventoried roadless areas (including those Multiple ID, MT encompassed in the Northern Rockies Ecosystem Protection Act) (Individual, Bemidji, MN - #7964.64351) Roadless areas in Montana Multiple MT (Individual, Olga, WA - #16638.10110) Pioneer Scenic Byway in southwest Montana Beaverhead MT (Individual, Butte, MT - #50515.64351) West Big Hole area Beaverhead MT (Individual, Minneapolis, MN - #2892.83000) Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, along the Selway River, and the Beaverhead-Deerlodge, MT Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness, at Johnson lake, the Pioneer Bitterroot Mountains in the Beaverhead-Deerlodge National Forest and the Great Bear Wilderness (Individual, Missoula, MT - #16940.90200) CLEARWATER NATIONAL FOREST: NORTH FORK Bighorn, Clearwater, Idaho ID, MT, COUNTRY- Panhandle, Lolo WY MALLARD-LARKINS--1300 (also on the Idaho Panhandle National Forest)….encompasses most of the high country between the St. Joe and North Fork Clearwater Rivers….a low elevation section of the North Fork Clearwater….Logging sales (Lower Salmon and Dworshak Blowdown) …a potential wild and scenic river section of the North Fork... THE GREAT BURN--1301 (or Hoodoo also on the Lolo National Forest) … harbors the incomparable Kelly Creek and includes its confluence with Cayuse Creek. This area forms a major headwaters for the North Fork of the Clearwater. …Fish Lake… the Jap, Siam, Goose and Shell Creek drainages WEITAS CREEK--1306 (Bighorn-Weitas)…Weitas Creek…North Fork Clearwater. -

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC)

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Summits on the Air USA - Colorado (WØC) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S46.1 Issue number 3.2 Date of issue 15-June-2021 Participation start date 01-May-2010 Authorised Date: 15-June-2021 obo SOTA Management Team Association Manager Matt Schnizer KØMOS Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Page 1 of 11 Document S46.1 V3.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Change Control Date Version Details 01-May-10 1.0 First formal issue of this document 01-Aug-11 2.0 Updated Version including all qualified CO Peaks, North Dakota, and South Dakota Peaks 01-Dec-11 2.1 Corrections to document for consistency between sections. 31-Mar-14 2.2 Convert WØ to WØC for Colorado only Association. Remove South Dakota and North Dakota Regions. Minor grammatical changes. Clarification of SOTA Rule 3.7.3 “Final Access”. Matt Schnizer K0MOS becomes the new W0C Association Manager. 04/30/16 2.3 Updated Disclaimer Updated 2.0 Program Derivation: Changed prominence from 500 ft to 150m (492 ft) Updated 3.0 General information: Added valid FCC license Corrected conversion factor (ft to m) and recalculated all summits 1-Apr-2017 3.0 Acquired new Summit List from ListsofJohn.com: 64 new summits (37 for P500 ft to P150 m change and 27 new) and 3 deletes due to prom corrections.