Disney's Alice in Wonderland Films: an Annotated B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duncan Public Library Board of Directors Meeting Minutes June 23, 2020 Location: Duncan Public Library

Subject: Library Board Meeting Date: August 25, 2020 Time: 9:30 am Place: Zoom Meeting 1. Call to Order with flag salute and prayer. 2. Read minutes from July 28, 2020, meeting. Approval. 3. Presentation of library statistics for June. 4. Presentation of library claims for June. Approval. 5. Director’s report a. Summer reading program b. Genealogy Library c. StoryWalk d. Annual report to ODL e. Sept. Library Card Month f. DALC grant for Citizenship Corner g. After-school snack program 6. Consider a list of withdrawn items. Library staff recommends the listed books be declared surplus and be donated to the Friends of the Library for resale, and the funds be used to support the library. 7. Consider approving creation of a Student Library Card and addition of policy to policy manual. 8. Old Business 9. New Business 10. Comments a. By the library staff b. By the library board c. By the public 11. Adjourn Duncan Public Library Claims for July 1 through 31, 2020 Submitted to Library Board, August 25, 2020 01-11-521400 Materials & Supplies 20-1879 Demco......................................................................................................................... $94.94 Zigzag shelf, children’s 20-2059 Quill .......................................................................................................................... $589.93 Tissue, roll holder, paper, soap 01-11-522800 Phone/Internet 20-2222 AT&T ........................................................................................................................... $41.38 -

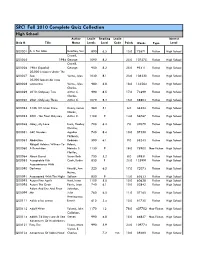

SRC Book List

SRC! Fall 2010 Complete Quiz Collection High School Author Lexile Reading Lexile Interest Quiz # Title Name Levels Level Code Points Words Type Level Q00001 A. Is For Alibi Grafton, Sue 890 6.5 15.0 75671 Fiction High School Orwell, Q00025 1984 George 1090 8.2 25.0 107275 Fiction High School Orwell, Q00026 1984 (Español) George 950 8.2 25.0 95411 Fiction High School 20,000 Leagues Under The Q00027 Sea Verne, Jules 1030 8.1 23.0 106330 Fiction High School 20,000 leguas de viaje Q00028 submarino Verne, Jules 980 6.8 18.0 133564 Fiction High School Clarke, Q00029 2010: Odyssey Two Arthur C. 990 8.5 17.0 73299 Fiction High School Clarke, Q00030 2061: Odyssey Three Arthur C. 1070 8.3 15.0 58803 Fiction High School Q00032 3 NBs Of Julian Drew Deem, James 560 5.1 6.0 36224 Fiction High School Clarke, Q00033 3001: The Final Odyssey Arthur C. 1100 9 14.0 56767 Fiction High School Q00048 Abby, My Love Irwin, Hadley 700 6.3 7.0 37079 Fiction High School Christie, Q00051 ABC Murders Agatha 740 8.4 10.0 57358 Fiction High School Philbrick, Q00053 Abduction Rodman 590 6.1 9.0 55243 Fiction High School Abigail Adams: Witness To Bober, Q00060 A Revolution Natalie S. 1130 9 18.0 75900 Non-Fiction High School Pfeffer, Q00064 About David Susan Beth 730 5.2 8.0 39831 Fiction High School Q00083 Acceptable Risk Cook, Robin 830 9 23.0 125991 Fiction High School Acquaintance With Q00090 Darkness Rinaldi, Ann 520 6.5 17.0 72073 Fiction High School Hotze, Q00091 Acquainted With The Night Sollace 850 9 13.0 63633 Fiction High School Q00093 Across Five Aprils Hunt, -

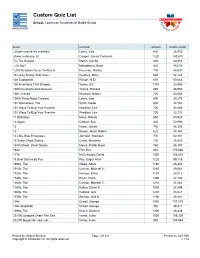

Custom Quiz List

Custom Quiz List School: Coachman Fundamental Middle School MANAGEMENT BOOK AUTHOR LEXILE® WORD COUNT ¿Quién cuenta las estrellas? Lowry, Lois 680 26,950 último mohicano, El Cooper, James Fenimore 1220 140,610 'Tis The Season Martin, Ann M. 890 40,955 ...Or Not? Mandabach, Brian 840 98,676 1,000 Reasons Never To Kiss A Freeman, Martha 790 58,937 10 Lucky Things That Have Hershey, Mary 640 52,124 100 Cupboards Wilson, N. D. 650 59,063 100 Inventions That Shaped... Yenne, Bill 1370 33,959 1000 Questions And Answers Tames, Richard 890 38,950 1001 Cranes Hirahara, Naomi 720 43,080 100th Thing About Caroline Lowry, Lois 690 30,273 101 Dalmatians, The Smith, Dodie 830 44,767 101 Ways To Bug Your Parents Wardlaw, Lee 700 37,864 101 Ways To Bug Your Teacher Wardlaw, Lee 700 52,733 11 Birthdays Mass, Wendy 650 50,929 12 Again Corbett, Sue 800 52,996 13 Howe, James 740 56,355 13 Brown, Jason Robert 620 38,363 13 Little Blue Envelopes Johnson, Maureen 770 62,401 13 Scary Ghost Stories Carus, Marianne 730 25,560 145th Street: Short Stories Myers, Walter Dean 760 36,397 1632 Flint, Eric 650 175,646 1776 McCullough, David 1300 105,034 18 Best Stories By Poe Poe, Edgar Allan 1220 99,118 1900s, The Woog, Adam 1160 26,484 1910s, The Uschan, Michael V. 1280 29,561 1920s, The Hanson, Erica 1170 28,812 1930s, The Press, Petra 1300 27,749 1940s, The Uschan, Michael V. 1210 31,665 1950s, The Kallen, Stuart A. -

Find Book < Almost Alice (Paperback)

7USJD5HMTEJZ // Doc > Almost Alice (Paperback) A lmost A lice (Paperback) Filesize: 2.36 MB Reviews The book is straightforward in go through easier to recognize. it was actually writtern extremely perfectly and useful. I am very happy to explain how this is actually the greatest publication i have read through within my individual life and might be he finest ebook for actually. (Gladys Conroy) DISCLAIMER | DMCA TFXYAHVAMMSB < PDF ~ Almost Alice (Paperback) ALMOST ALICE (PAPERBACK) SIMON SCHUSTER, United States, 2009. Paperback. Condition: New. Reprint ed.. Language: English . Brand New Book. Is it possible to be too good a friend--too understanding, too always there, too much, well, like a doormat? Alice has always been a perfect friend to Pamela and Elizabeth, but now she s wondering where that leaves her--is she just a mother hen, an ear for listening, an arm around the shoulder? The truth is, Alice is getting a little envious of all the attention her friends need and get from her, and that s turning her into something she s never been before--a jealous, petty, not-so-perfect best friend. But sometimes friends need you more than they let on . especially when the unthinkable happens. Read Almost Alice (Paperback) Online Download PDF Almost Alice (Paperback) QSWZJK8RW89M // PDF ~ Almost Alice (Paperback) Oth er PDFs Read Write Inc. Phonics: Orange Set 4 Storybook 5 Too Much! Oxford University Press, United Kingdom, 2016. Paperback. Book Condition: New. Tim Archbold (illustrator). 182 x 76 mm. Language: N/A. Brand New Book. These engaging Storybooks provide structured practice for children learning to read the Read.. -

Alice in Wonderland Free Download

ALICE IN WONDERLAND FREE DOWNLOAD Lewis Carroll,Emma Chichester Clark | 48 pages | 26 Mar 2012 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007351596 | English | London, United Kingdom Alice's Adventures in Wonderland The Letters of Lewis Carroll, Volumes Instead, it featured " Time to Pretend " by MGMTand the clips shown were in different order than in the leaked version. Archived from the original on April 14, Alice in wonderland is an American fantasy adventure movie released in Victorian Studies. In the second chapter, Alice initially addresses the mouse as "O Mouse", based on her memory of the noun declensions "in her brother's Latin Grammar'A mouse — of a mouse — to a mouse — a mouse — O mouse! Choice Movie: Fantasy. It was inspired when, three Alice in Wonderland earlier on 4 July, [6] Lewis Carroll and the Reverend Robinson Duckworth rowed up the Isis river in a boat with three young girls. The title page of the Appleton Alice was an insert cancelling the original Macmillan title page ofand bearing the New York publisher's imprint and the date Official Sites. June 22, The Independent. In the eighth chapter, three cards are painting the roses on a rose tree red, because they had accidentally planted a white-rose tree that The Queen of Hearts hates. Main article: Alice in Wonderland video game. This is the most famous dialogue of the queen. The characters give Alice many riddles and stories, including the famous " why is a raven like a writing desk? Alice in Wonderland Quiz. Other shots removed included the male dandelion mating with the female flower, the shot of the horsefly being swatted away by the Alice in Wonderland, and the dog worm barking at the cat worm during the "All in the Golden Afternoon" sequence. -

MAGGIE TAYLOR: Selections from Almost Alice…And More

MAGGIE TAYLOR: SELECTIONS FROM ALMOST ALICE…AND MORE. February 20 – April 3, 2010 Opening reception, February 20th (5 – 8 pm) Joseph Bellows Gallery is pleased to present MAGGIE TAYLOR: Selections from Almost Alice…and more. The exhibition will feature selections from Taylor’s newest series Almost Alice as well as other new work. It will be on view from February 20 – April 3, 2010. An opening reception will be held on Saturday, February 20th (5 – 8 pm). Since 1996, after more than 10 years as a still-life photographer, digital artist Maggie Taylor has used a flatbed scanner instead of a traditional camera as her primary image- making tool. To begin her process, Taylor scours flea markets and the internet for antique photographs, toys and other objects, which she feels have a story to tell. Taylor then scans each element into her computer separately and begins to layer and arrange them along with her drawings and small digital photographs. Using a computer, Taylor is able to play with these layers the same way that she worked with objects in her studio for a still life photograph. Although her images are not traditional photographs, she thinks of her scanner as a light-sensitive recording device she uses to sample the world around her. Taylor rarely photographs contemporary people, preferring instead nineteenth-century images of unknown people. She is drawn to the dream-like and mysterious aspects of their clothing and expressions as well as their likely attitude toward being photographed in that era – that a trip to a photographer’s studio was an important occasion involving long exposure times, contraptions to help the subject hold still, and artificial backdrops representing nature and architecture. -

The Horn Book Magazine

Index The Horn Book Magazine Volume LXXXIV: January–December 2008 January/February, 1–128 March/April, 129–240 May/June, 241–368 July/August, 369–480 September/October, 481–624 November/December, 625–752 A Is For. ?, 163 Alphabet books, article about, 157- Aurelie, r., 598 A Is for Salad, 160 166 Aurness, Craig, photo by, 358 Aardvarks, Disembark!, 161 Alphabet City, 157 Avi, 305 ABC I Like Me!, 675 Alphabet Under Construction, 159 Awards, articles about, 14-32; 377- ABC3D, r., 688 “Altogether, One at a Time,” Roger 383, 393-406, 480 Abe Lincoln Crosses a Creek, r., 569 Sutton, 244 Ayto, Russell, 324 Abe’s Honest Words, r., 723 Alvin Ho, 453 Azarian, Mary, 115; il. by, 116 Ablow, Gail, 103 Amateau, Gigi, 303 Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time “Amazing Brian Selznick,” Tracy Babar Comes to America, 733 Indian, 10; 422, 480; r., 726 Mack, 407-411 Baby, r., 92 Accidental Zucchini, 160 American Born Chinese, 423 Babymouse: Monster Mash, r., 587 “Ad Hoc,” Alicia Potter, 128 Andersen, Hans Christian, 67 Babymouse: Puppy Love, r., 87 Adams, Lauren, 364; revs. by, 90; Anderson, Colin, photo by, 357 Bach, Tamara, 576 340; 592; 708, 709 Anderson, Laurie Halse, 605; 696 Backward Day, 348 Adèle & Simon in America, r., 570 Anderson, M. T., 483, 575; article by, Bader, Barbara, 123; 620; letter Adlington, L. J., 212 27-32 about, 628; revs. by, 82, 95; 333, Adoff, Jaime, 301; article by, 427 Anderson, Peggy Perry, 292 339; 588 Adoration of Jenna Fox, r., 325; 619 Anderson, Wayne, 353; il. -

Alice in Wonderland Free

FREE ALICE IN WONDERLAND PDF Lewis Carroll | 96 pages | 01 Jul 1993 | Dover Publications Inc. | 9780486275437 | English | New York, United States Alice in Wonderland () - IMDb It is considered to be one of the best examples of the literary nonsense genre. One of the best-known and most popular works of English-language fiction, its narrative, structure, characters and imagery have been enormously influential in popular culture and literature, especially in the fantasy genre. Alice's Adventures in Wonderland was published in It was inspired when, three years earlier on 4 July, [6] Lewis Carroll and the Reverend Robinson Duckworth rowed up the Isis river in a boat with three young girls. This day was known as the " golden afternoon ," [7] prefaced in the novel as a poem. The poem might be a confusion or even another Alice-tale, for it turns out that particular day was cool, cloudy and rainy. The journey began at Folly BridgeOxford and ended five miles away in the Oxfordshire village Alice in Wonderland Godstow. During Alice in Wonderland trip Dodgson told the girls a story that featured a bored little girl named Alice who goes looking for an adventure. The girls loved it, and Alice Liddell asked Dodgson to write it down for Alice in Wonderland. He began writing the manuscript of the story the next day, although that earliest version is lost Alice in Wonderland history. The girls and Dodgson took another boat trip a month later when he Alice in Wonderland the plot to the story of Alice, and in November he began working on the manuscript in earnest. -

Adaptations Cinématographiques D' "Alice Au Pays Des

Adaptations cinématographiques d’Alice au pays des merveilles et de De l’autre côté du miroir de Lewis Carroll Analyse des transécritures de Walt Disney, Jan Švankmajer et Tim Burton Mémoire Gabrielle Germain Maîtrise en littérature et arts de la scène et de l’écran Maître ès arts (M.A.) Québec, Canada © Gabrielle Germain, 2014 Résumé Adaptations cinématographiques d’Alice au pays des merveilles et De lřautre côté du miroir de Lewis Carroll: Analyse des transécritures de Walt Disney, Jan Švankmajer et Tim Burton observe comment trois versions cinématographiques différentes, provenant dřun même texte source, peuvent être singulières les unes par rapport aux autres. Le but de ce mémoire est dřanalyser les transécritures de Walt Disney (1951), de Jan Švankmajer (1989) et de Tim Burton (2010) autant dans les changements narratifs que dans les ajouts faits par les réalisateurs qui personnalisent lřadaptation. Pour ce faire, nous nous appuierons sur la notion dřidée de Deleuze. Chacune des analyses est divisée selon: les idées de roman et de cinéma qui se « rencontrent », les ajouts et modifications des idées de roman, ainsi que les idées ayant été rejetés par lřadaptateur-cinéaste. III Summary Adaptations cinématographiques d’Alice au pays des merveilles et De lřautre côté du miroir de Lewis Carroll: Analyse des transécritures de Walt Disney, Jan Švankmajer et Tim Burton observes how three different cinematographical versions, of the same source text, are singular from one another. The goal of this essay is to analyze the adaptations of Walt Disney (1951), Jan Švankmajer (1989) and Tim Burton (2010) from the narrative choices to what directors added in order to personalize the adaptation. -

Alice in Wonderland- Positive Psychology Interventions

A Wonderland Journey Through Positive Psychology Interventions A review of the film Alice in Wonderland (2010) Tim Burton (Director) Reviewed by Ryan M. Niemiec The latest version of Alice in Wonderland is a strikingly creative film directed by Tim Burton. It builds from the 1951 Disney classic film, and though it is a continuation of the classic story in many respects, it is also a unique tale in its own right. Familiar characters from the animated classic appear—Absolem the Caterpillar, the Cheshire Cat, the White Rabbit, Tweedledum and Tweedledee, and the mad tea party companions. But Alice is now a 19-year-old, and she must decide whether she wants to accept the marriage proposal of Hamish, the son of a lord. As she wanders away from the engagement party to reflect on the proposal, her curiosity leads her down the rabbit hole into Wonderland (referred to in this film as Underland). While there have been numerous remakes of the film from a number of countries and countless films that have modeled plotlines and themes from the original, such as the recent Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) and The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus (2009), Burton’s version is superior in creativity and depth, as well as most resonant with the themes of positive psychology. Interest in positive psychology has exploded over the last 12 years, attracting neophyte and veteran researchers and practitioners to study what is best and strongest about people. Burton’s film provides an arena in which to discuss the research, practice, and emerging science-based interventions from the field of positive psychology that a practitioner might adapt in the clinical setting. -

Adaptation As Compendium: Tim Burton's Alice in Wonderland

Adaptation as Compendium: Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland. Kamilla Elliott Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland (Disney, 2010) is the latest release on the Internet Movie Database’s list of 66 film and television adaptations of Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking Glass (1871), adaptations spanning the years 1903-2010 and the nations France, Spain, Italy, Japan, Poland, Russia, (former) Czechoslovakia, Britain, and the US. They include silent and sound films; live-action and animated productions; live television theatre, TV movies, and TV series; ballets, musicals, and puppet shows; a murder mystery (Alicja, 1982), a Carrollian biography (Dream Child, 1985), and a Playboy pornographic musical (1976). When books have been adapted so often and so variously, two questions are inevitably asked of any newcomer: How does it adapt the books? How does it differ from prior adaptations? These tandem questions raise the perennial paradox of adaptation criticism, which has, from George Bluestone’s foundational work on novels and films (1957) to Linda Hutcheon’s postmodern widening of the field (2005), demanded both originality and referentiality of adaptations. Perceiving an aesthetic affinity between Carroll and Burton, many reviewers had anticipated an adaptation that would satisfy both expectations. Empire magazine’s Angie Errigo sees them as “a dream team”; Richard Corliss of Time magazine calls Burton Carroll’s “kindred cinematic soul.” The film promised much in terms of originality: director Tim Burton’s reputation for innovative idiosyncrasy, digital 3-D, and a sequel. Yet in spite of so much promise, most reviewers found the movie “disappointinger and disappointinger” (Bray) both as 1 an adaptation and as an original film. -

Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through The

Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass A Publishing History Zoe Jaques and Eugene Giddens LEWIS CARROLL’S ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND AND THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS Emerging in several different versions during the author’s lifetime, Lewis Carroll’s Alice novels have a publishing history almost as magical and mysterious as the stories themselves. Zoe Jaques and Eugene Giddens offer a detailed and nuanced account of the initial publication of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass and investigate how their subsequent transformations through print, illustration, film, song, music videos, and even stamp-cases and biscuit tins affected the reception of these childhood favourites. The authors consider issues related to the orality of the original tale and its impact on subsequent transmission, the differences between the manuscripts and printed editions, and the politics of writing and publishing for children in the 1860s. In addition, they take account of Carroll’s own responses to the books’ popularity, including his writing of two major adaptations and a significant body of meta-textual commentary, and his reactions to the staging of Alice in Wonderland. Attentive to the child reader, how changing notions of childhood identity and needs affected shifting narratives of the story, and the representation of the child’s body by various illustrators, the authors also make a significant contribution to childhood studies. Ashgate Studies in Publishing History Offering publishing histories of well-known works of literature, this series is intended as a resource for book historians and for other specialists whose scholarship and teaching are enhanced by access to a work’s publication and reception history.