Restructuring the Indian Council of Social Science Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Part 05.Indd

PART MISCELLANEOUS 5 TOPICS Awards and Honours Y NATIONAL AWARDS NATIONAL COMMUNAL Mohd. Hanif Khan Shastri and the HARMONY AWARDS 2009 Center for Human Rights and Social (announced in January 2010) Welfare, Rajasthan MOORTI DEVI AWARD Union law Minister Verrappa Moily KOYA NATIONAL JOURNALISM A G Noorani and NDTV Group AWARD 2009 Editor Barkha Dutt. LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI Sunil Mittal AWARD 2009 KALINGA PRIZE (UNESCO’S) Renowned scientist Yash Pal jointly with Prof Trinh Xuan Thuan of Vietnam RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL GAIL (India) for the large scale QUALITY AWARD manufacturing industries category OLOF PLAME PRIZE 2009 Carsten Jensen NAYUDAMMA AWARD 2009 V. K. Saraswat MALCOLM ADISESHIAH Dr C.P. Chandrasekhar of Centre AWARD 2009 for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. INDU SHARMA KATHA SAMMAN Mr Mohan Rana and Mr Bhagwan AWARD 2009 Dass Morwal PHALKE RATAN AWARD 2009 Actor Manoj Kumar SHANTI SWARUP BHATNAGAR Charusita Chakravarti – IIT Delhi, AWARDS 2008-2009 Santosh G. Honavar – L.V. Prasad Eye Institute; S.K. Satheesh –Indian Institute of Science; Amitabh Joshi and Bhaskar Shah – Biological Science; Giridhar Madras and Jayant Ramaswamy Harsita – Eengineering Science; R. Gopakumar and A. Dhar- Physical Science; Narayanswamy Jayraman – Chemical Science, and Verapally Suresh – Mathematical Science. NATIONAL MINORITY RIGHTS MM Tirmizi, advocate – Gujarat AWARD 2009 High Court 55th Filmfare Awards Best Actor (Male) Amitabh Bachchan–Paa; (Female) Vidya Balan–Paa Best Film 3 Idiots; Best Director Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots; Best Story Abhijat Joshi, Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Male) Boman Irani–3 Idiots; (Female) Kalki Koechlin–Dev D Best Screenplay Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Abhijat Joshi–3 Idiots; Best Choreography Bosco-Caesar–Chor Bazaari Love Aaj Kal Best Dialogue Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra–3 idiots Best Cinematography Rajeev Rai–Dev D Life- time Achievement Award Shashi Kapoor–Khayyam R D Burman Music Award Amit Tivedi. -

Of Contemporary India

OF CONTEMPORARY INDIA Catalogue Of The Papers of Prabhakar Machwe Plot # 2, Rajiv Gandhi Education City, P.O. Rai, Sonepat – 131029, Haryana (India) Dr. Prabhakar Machwe (1917-1991) Prolific writer, linguist and an authority on Indian literature, Dr. Prabhakar Machwe was born on 26 December 1917 at Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India. He graduated from Vikram University, Ujjain and obtained Masters in Philosophy, 1937, and English Literature, 1945, Agra University; Sahitya Ratna and Ph.D, Agra University, 1957. Dr. Machwe started his career as a lecturer in Madhav College, Ujjain, 1938-48. He worked as Literary Producer, All India Radio, Nagpur, Allahabad and New Delhi, 1948-54. He was closely associated with Sahitya Akademi from its inception in 1954 and served as Assistant Secretary, 1954-70, and Secretary, 1970-75. Dr. Machwe was Visiting Professor in Indian Studies Departments at the University of Wisconsin and the University of California on a Fulbright and Rockefeller grant (1959-1961); and later Officer on Special Duty (Language) in Union Public Service Commission, 1964-66. After retiring from Sahitya Akademi in 1975, Dr. Machwe was a visiting fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies, Simla, 1976-77, and Director of Bharatiya Bhasha Parishad, Calcutta, 1979-85. He spent the last years of his life in Indore as Chief Editor of a Hindi daily, Choutha Sansar, 1988-91. Dr. Prabhakar Machwe travelled widely for lecture tours to Germany, Russia, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Japan and Thailand. He organised national and international seminars on the occasion of the birth centenaries of Mahatma Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore, and Sri Aurobindo between 1961 and 1972. -

Annual Report 2014–15 © 2015 National Council of Applied Economic Research

National Council of Applied Economic Research Annual Report Annual Report 2014–15 2014–15 National Council of Applied Economic Research Annual Report 2014–15 © 2015 National Council of Applied Economic Research August 2015 Published by Dr Anil K. Sharma Secretary & Head Operations and Senior Fellow National Council of Applied Economic Research Parisila Bhawan, 11 Indraprastha Estate New Delhi 110 002 Telephone: +91-11-2337-9861 to 3 Fax: +91-11-2337-0164 Email: [email protected] www.ncaer.org Compiled by Jagbir Singh Punia Coordinator, Publications Unit ii | NCAER Annual Report 2014-15 NCAER | Quality . Relevance . Impact The National Council of Applied Economic Research, or NCAER as it is more commonly known, is India’s oldest and largest independent, non-profit, economic policy research institute. It is also one of a handful of think tanks globally that combine rigorous analysis and policy outreach with deep data collection capabilities, especially for household surveys. NCAER’s work falls into four thematic NCAER’s roots lie in Prime Minister areas: Nehru’s early vision of a newly- independent India needing independent • Growth, macroeconomics, trade, institutions as sounding boards for international finance, and economic the government and the private sector. policy; Remarkably for its time, NCAER was • The investment climate, industry, started in 1956 as a public-private domestic finance, infrastructure, labour, partnership, both catering to and funded and urban; by government and industry. NCAER’s • Agriculture, natural resource first Governing Body included the entire management, and the environment; and Cabinet of economics ministers and • Poverty, human development, equity, the leading lights of the private sector, gender, and consumer behaviour. -

Language and Literature

1 Indian Languages and Literature Introduction Thousands of years ago, the people of the Harappan civilisation knew how to write. Unfortunately, their script has not yet been deciphered. Despite this setback, it is safe to state that the literary traditions of India go back to over 3,000 years ago. India is a huge land with a continuous history spanning several millennia. There is a staggering degree of variety and diversity in the languages and dialects spoken by Indians. This diversity is a result of the influx of languages and ideas from all over the continent, mostly through migration from Central, Eastern and Western Asia. There are differences and variations in the languages and dialects as a result of several factors – ethnicity, history, geography and others. There is a broad social integration among all the speakers of a certain language. In the beginning languages and dialects developed in the different regions of the country in relative isolation. In India, languages are often a mark of identity of a person and define regional boundaries. Cultural mixing among various races and communities led to the mixing of languages and dialects to a great extent, although they still maintain regional identity. In free India, the broad geographical distribution pattern of major language groups was used as one of the decisive factors for the formation of states. This gave a new political meaning to the geographical pattern of the linguistic distribution in the country. According to the 1961 census figures, the most comprehensive data on languages collected in India, there were 187 languages spoken by different sections of our society. -

Syllabus for M.Sc. (Film Production)| 1

Syllabus for M.Sc. (Film Production)| 1 Detailed Syllabus for Master of Science (Film Production) (Effective from July 2019) Department of Advertising & Public Relations Makhanlal Chaturvedi National University of Journalism and Communication B-38, Press Complex, M.P. Nagar, Zone-I, Bhopal (M.P.) 462 011 Syllabus for M.Sc. (Film Production)| 2 MAKHANLAL CHATURVEDI NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF JOURNALISM AND COMMUNICATION (DEPARTMENT OF ADVERTISING AND PUBLIC RELATIONS) Master of Science (Film Production) (Effective from July 2019) Marks Distribution Subject Theory Practic Intern Total Credit al al CCC-1 Evolution of Cinema 80 00 20 100 6 CCC-2 Origin and Growth of Media 80 00 20 100 6 Introduction to Socio CCC-3 80 00 20 100 6 Economic Polity Sem - I CCE-1 Art of Cinematography 50 30 20 OR OR 100 6 CCE-2 Storyboarding 50 30 20 OE-1 Understanding Cinema 25 15 10 50 3 CCC-4 Drama & Aesthetics 50 30 20 100 6 CCC-5 Lighting for Cinema 50 30 20 100 6 CCC-6 Audiography 50 30 20 100 6 Sem - II CCE-3 Art of Film Direction 50 30 20 OR OR 100 6 CCE-4 Film Journalism 50 30 20 OE-2 Ideation and Visualization 25 15 10 50 3 CCC-7 Multimedia Platform 50 30 20 100 6 Editing Techniques & CCC-8 50 30 20 100 6 Practice CCC-9 Film Research 50 30 20 100 6 Sem - III Screenplay Writing for CCE-5 50 30 20 Cinema OR 100 6 OR CCE-6 50 30 20 Advertisement Film Making OE-3 Film Society & Culture 40 00 10 50 3 CCC-10 Film Business & Regulations 80 00 20 100 6 CCC-11 Cinematics 50 30 20 100 6 CCC-12 Project Work on Film Making 00 80 20 100 6 Sem - Literature & Cinema CCE-7 80 00 20 IV OR OR 100 6 Film Management & CCE-8 80 00 20 Marketing OE-4 Documentary Film Making 25 15 10 50 3 Syllabus for M.Sc. -

Anant Kumar, M.Phil., Ph.D

CURRICULUM VITAE Anant Kumar, M.Phil., Ph.D. (JNU) Mobile: 91-9934160637 Associate Professor Tel: (O) 91-651-2200873 Exrn. 401 Xavier Institute of Social Service Tel: (R) 91-651-6452110 Dr. Camil Bulcke Path, Ranchi – 834001 E-mail: [email protected] Present Position: Fulbright-Nehru Academic and Professional Excellence Fellow at the Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, USA. (Sept 2015- Contd.) Associate Professor in the Department of Rural Management at Xavier Institute of Social Service (XISS), Ranchi, Jharkhand, India. (13th Oct 2006 – Contd.). Research Associate, IntraHealth International, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, USA. (June 2015- Contd.). Affiliate, Global Gender Center, RTI International, Raleigh-Durham, NC, USA (Oct 2015 – Contd.) Member of the Board of Directors, Canadian Coalition for Global Health Research (November 2014 – Contd.). Member, Editorial Board, Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, Routledge. (Jan 2015 – contd.) Member, Editorial Board, New Horizons in Translational Medicine, Elsevier. (Oct 2015 – contd.) Member, Editorial Board, International NGO Journal (INGOJ). Member, Editorial Board, Jharkhand Journal of Social Development. (2009 – Contd.). Member, Jharkhand State Mentoring Monitoring Committee under National Rural Health Mission (2007 – Contd.). Member, Expert Committee, Rehabilitation Council of India (RCI). (2005 – Contd.) Academic Qualifications: Education History Degree Institution & University Degree/ Subjects Dates Division Names Ph. D. Jawaharlal Nehru University, Social Medicine and 2001-2006 Awarded New Delhi Community Health M. Phil. Jawaharlal Nehru University, M. Phil (Social Medicine) 1999-2001 1st New Delhi Post Allahabad University, M.A. (Psychology) 1996-98 1st Graduation Allahabad, UP Graduation Allahabad University, B.A. (Psychology, Modern 1993-96 1st Allahabad, UP History & Political Science) Pre A.N. -

Curriculum Vitae of Prof. M.V. Nadkarni

CURRICULUM VITAE OF PROF. M.V. NADKARNI (as updated on 24th December, 2017) Full name : Mangesh Venkatesh Nadkarni Present position and address : Hon. Visiting Professor Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC) Nagarabhavi PO, Bangalore 560 072 Residence address : 40/1, ‘Samagama’, 2nd Cross to West from ISEC Nagarabhavi PO, Bangalore 560 072 Phone : 080 – 23213677, 9844213677 E-mail: [email protected] Education : Ph.D (Economics) 1968 (Karnatak) M.A. (Economics) 1961 (Karnatak) Fields of Interest Agricultural/rural development, price policy, production economics, problems of drought-prone areas; environmental economics: particularly forest issues, pollution control, environment and economic development; political economy; social development; Gandhian thought; religion and philosophy – esp. social, economic and environmental dimensions. Substantive Positions National Fellow, ICSSR, from 18th November 2002 to 17th November 2004. Vice Chancellor, Gulbarga University, Gulbarga, February 18, 1999 to February 17, 2002. Professor and Head, Ecological Economics Unit at ISEC, April 1981 – February 1999. Professor, Rural Economics Unit at ISEC, Bangalore, 1976-81. Reader (Economics), Marathwada University, Aurangabad (Maharashtra) 1972-76. Lecturer (Economics), Marathwada University, Aurangabad (Maharashtra), 1968-72. Research Assistant (Economics) Karnatak University, Dharwar (Karnatak), 1962-68. Honorary Positions and Membership of Learned Societies Member, Governing Council, Centre for Multi-Disciplinary Development Research, Dharwad. Chairman, Governing Council, Centre for Multi-Disciplinary Development Research, Dharwad (2007-09). Founder Trustee of the Centre for Inter-disciplinary Studies in Environment and Development since its inception in 2002 up to its merger with ATREE in 2009 Chairman, Editorial Board, Indian Journal of Agricultural Economics (Jan. 2005 to Dec 2007) Elected President for the 55th Annual Conference of the Indian Society of Agricultural Economics at IRMA, Anand, 1995. -

![Makhanlal Chaturvedi Govt. Girls College Khandwa[MP]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0436/makhanlal-chaturvedi-govt-girls-college-khandwa-mp-800436.webp)

Makhanlal Chaturvedi Govt. Girls College Khandwa[MP]

1 Makhanlal Chaturvedi Govt. Girls College Khandwa[M.P.] Annual Report 2016-17 This format outlines the annual reports to be published by all colleges in the Madhya Pradesh on their websites, by October 31st of each year. Part I is intended as a guide and colleges are free to alter the contents and format as they see fit. Part II, the Appendix (Institutional Performance Data and Financial Reports), is mandatory and colleges are required to report all data as per the attached format and instructions. Important Information – Name of the college –Makhanlal Chaturvedi Govt.Girls P.G. College Place of the college –Padawa Indore Road Khandwa District -Khandwa Division -Indore Year of establishment of college -1964 Name and Contact details( Mail id , Phone ) of Principal -Dr.Pushaplata Kesari. [email protected] PH.-0733-2244097,Fax-07332244050 Name , Post and Contact details of ( mail id, Phone no.) of Reporting In charge - Date of report submission -21-08-2017 Part I 1.The Principal’s Report (2 pages)- Highlights the key activities, events, and successes of the past year and briefly describes major new initiatives to be undertaken over the next year. Makhanlal Chaturvedi Government Girls Post Graduate College a prime women educational institution for women in East Nimar district of Madhya Pradesh was established in 1963. Institution has been named in the honour of Padmashri Makhanlal Chaturvedi a great poet and freedom fighter of India. The institution is affiliated to Devi Ahilya Vishvavidyalaya, Indore (M.P.) since 1966. It is recognized by UGC under 2f and 12 B in July 1966 at that time it was affiliated to Dr. -

Academic Freedom and Indian Universities

SPECIAL ARTICLE Academic Freedom and Indian Universities Nandini Sundar Academic freedom is increasingly under assault from Theirs (the universities’) is the pursuit of truth and excellence in all its diversity—a pursuit which needs, above all, courage and fearlessness. authoritarian governments worldwide, supported by Great universities and timid people go ill together. right-wing student groups who act as provocateurs —Kothari Commission Report (1966: 274) within. In India, recent assaults on academic freedom s Indian universities reel under the multiple batteries of have ranged from curbs on academic and extracurricular privatisation, Hindutva, and bureaucratic indifference, events to brutal assaults on students. However, the A it is useful to recall older visions of the Indian university and the centrality of academic freedom to defi ning this idea. concept of academic freedom is complex and needs to Historically, the goals of the Indian university have included be placed in a wider institutional context. While training human resources for national growth, reducing academic freedom was critical to earlier visions of the inequality by facilitating individual and community mobility, Indian university, as shown by various commissions on pushing the frontiers of research and knowledge, and keeping alive a spirit of enquiry and criticism. The last, however, is no higher education, it is now increasingly devalued in longer seen as important. favour of administrative centralisation and Ostensibly worried by India’s plummeting rank in inter- standardisation. Privatisation and the increase in national higher education comparisons,1 the government has precarious employment also contribute to the shrinking proposed to set up “world class” educational institutes (UGC 2016), and grant autonomy to 60 specifi ed institutions (MHRD of academic freedom. -

Tribal Women in the Democratic Political Process a Study of Tribal Women in the Dooars and Terai Regions of North Bengal

TRIBAL WOMEN IN THE DEMOCRATIC POLITICAL PROCESS A STUDY OF TRIBAL WOMEN IN THE DOOARS AND TERAI REGIONS OF NORTH BENGAL A Thesis submitted to the University of North Bengal For the Award of Doctor of Philosophy In Department of Political Science By Renuca Rajni Beck Supervisor Professor Manas Chakrabarty Department of Political Science University of North Bengal August, 2018 Dedicated To My Son Srinjoy (Kutush) ABSTRACT Active participation in the democratic bodies (like the local self-government) and the democratic political processes of the marginalized section of society like the tribal women can help their empowerment and integration into the socio-political order and reduces the scope for social unrest. The present study is about the nature of political participation of tribal women in the democratic political processes in two distinctive areas of North Bengal, in the Dooars of Jalpaiguri district (where economy is based on tea plantation) and the Terai of Darjeeling district (with agriculture-based economy). The study would explore the political social and economic changes that political participation can bring about in the life of the tribal women and tribal communities in the tea gardens and in the agriculture-based economy. The region known as North Bengal consists of six northern districts of West Bengal, namely, Darjeeling, Jalpaiguri, Malda, Uttar Dinajpur, Dakshin Dinajpur and Cooch Behar. There is more than 14.5 lakh tribal population in this region (which constitutes 1/3rd of the total tribal population of the State), of which 49.6 per cent are women. Jalpaiguri district has the highest concentration of tribal population as 14.56 per cent of its population is tribal population whereas Darjeeling has 4.60 per cent of its population as tribal population. -

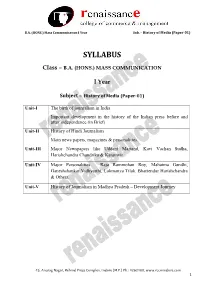

BA (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year

B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) SYLLABUS Class – B.A. (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year Subject – History of Media (Paper-01) Unit-I The birth of journalism in India Important development in the history of the Indian press before and after independence (in Brief) Unit-II History of Hindi Journalism Main news papers, magazines & personalities. Unit-III Major Newspapers like Uddant Martand, Kavi Vachan Sudha, Harishchandra Chandrika & Karamvir Unit-IV Major Personalities – Raja Rammohan Roy, Mahatma Gandhi, Ganeshshankar Vidhyarthi, Lokmanya Tilak, Bhartendur Harishchandra & Others. Unit-V History of Journalism in Madhya Pradesh – Development Journey 45, Anurag Nagar, Behind Press Complex, Indore (M.P.) Ph.: 4262100, www.rccmindore.com 1 B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) UNIT-I History of journalism Newspapers have always been the primary medium of journalists since 1700, with magazines added in the 18th century, radio and television in the 20th century, and the Internet in the 21st century. Early Journalism By 1400, businessmen in Italian and German cities were compiling hand written chronicles of important news events, and circulating them to their business connections. The idea of using a printing press for this material first appeared in Germany around 1600. The first gazettes appeared in German cities, notably the weekly Relation aller Fuernemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien ("Collection of all distinguished and memorable news") in Strasbourg starting in 1605. The Avisa Relation oder Zeitung was published in Wolfenbüttel from 1609, and gazettes soon were established in Frankfurt (1615), Berlin (1617) and Hamburg (1618).