Revisiting the Jacquard Loom: Threads of History and Current Patterns in HCI Ylva Fernaeus Martin Jonsson Jakob Tholander School of Computer Science and Dept

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Silk-Weaving in Sweden During the 19Th Century. Textiles and Texts - an Evaluation of the Source Material

Thesis for the degree of Licentiate of Philosophy SILK-WEAVING IN SWEDEN DURING THE 19TH CENTURY. Textiles and texts - An evaluation of the source material. Martin Ciszuk Translation Magnus Persson www.enodios.se Department of Product and Production Development Design & Human Factors CHALMERS UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Gothenburg, Sweden 2012 Silk-weaving in Sweden during the 19th century. Textiles and texts - An evaluation of the source material. Martin Ciszuk © Martin Ciszuk, 2012 Technical report No. 71 ISSN 1652-9243 Department of Product and Production Development Chalmers University of Technology SE-412 96 Gothenburg SWEDEN Telephone: +46 (0)31- 772 10 00 Illustration: Brocatell, interior silk woven for Stockholm Royal pallace by Meyersson silk mill in Stock- holm 1849, woven from silk cultivated in Sweden, Eneberg collection 11.183-9:2 (Photo: Jan Berg Textilmuseet, Borås). Printed by Strokirk-Landströms AB Lidköping, Sweden, 2012 www.strokirk-landstroms.se Silk-weaving in Sweden during the 19th century. Textiles and texts - An evaluation of the source material. Martin Ciszuk Department of Product and Production Development Chalmers University of Technology Abstract Silk-weaving in Sweden during the 19th century. Textiles and texts - An evaluation of the source material. With the rich material available, 19th century silk-weaving invites to studies on industrialisation processes. The purpose of this licentiate thesis is to present and discuss an empirical material regarding silk production in Sweden in the 19th century, to examine the possibilities and problems of different kinds of materials when used as source materials, and to describe how this material can be systematized and analysed in relation to the perspective of a textile scientific interpretation. -

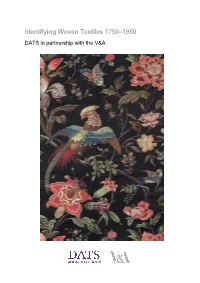

Identifying Woven Textiles 1750-1950 Identification

Identifying Woven Textiles 1750–1950 DATS in partnership with the V&A 1 Identifying Woven Textiles 1750–1950 This information pack has been produced to accompany two one-day workshops taught by Katy Wigley (Director, School of Textiles) and Mary Schoeser (Hon. V&A Senior Research Fellow), held at the V&A Clothworkers’ Centre on 19 April and 17 May 2018. The workshops are produced in collaboration between DATS and the V&A. The purpose of the workshops is to enable participants to improve the documentation and interpretation of collections and make them accessible to the widest audience. Participants will have the chance to study objects at first hand to help increase their confidence in identifying woven textile materials and techniques. This information pack is intended as a means of sharing the knowledge communicated in the workshops with colleagues and the wider public and is also intended as a stand-alone guide for basic weave identification. Other workshops / information packs in the series: Identifying Textile Types and Weaves Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740–1890 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Identifying Fibres and Fabrics Identifying Handmade Lace Front Cover: Lamy et Giraud, Brocaded silk cannetille (detail), 1878. This Lyonnais firm won a silver gilt medal at the Paris Exposition Universelle with a silk of this design, probably by Eugene Prelle, their chief designer. Its impact partly derives from the textures within the many-coloured brocaded areas and the markedly twilled cannetille ground. Courtesy Francesca Galloway. 2 Identifying Woven Textiles 1750–1950 Table of Contents Page 1. Introduction 4 2. Tips for Dating 4 3. -

The Jacquard Machine

The Jacquard Machine By Yoshito Miura, Yoshinosuke Nakajyo and Kunio Suzuki, Members,TMSJ Kyoto Technological University, Kyoto Abstract This article looks into problems which would accompany an attempt to increase the speed of looms equipped with a jacquard machine. Each lingo vibrates violently with an increase in speed. The grade of its vibrations was judged by the distribution of points of the lingo's descents. As a way to judge that state, sparks were discharged from a lingo placed on special re- cording paper. A controlled plate for the harness was devised in order to narrow the range of distribution of points of the lingo's descent. A plate was also devised to control the vibrations of the harness. The defective parts resulting from a speed increase were improved, and the warp tension and the weight of the lingo were investigated. The results of these efforts suggest that the speed of a loom equipped with a jacquard machine, at present, 130 rpm, can be increased to a maximum of 180 rpm. 1. Introduction be Y=--:;:2(1) ..... The speed of a loom equipped with a jacquard where a is the distance between the cloth fell and the forward surface of the shuttle; b, the distance machine is usually 90 to 130 rpm., considerably lower than the speed of a loom without a jacquard machine. between the cloth fell and the counpling or the It is mainly because of the shedding equipment and heald : and c, the height of the shuttle. the shuttle change equipment, but the shuttle change Assuming that N rpm is the speed of the loom will not be discussed here. -

Mügrip® Mbj8 1/1380

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATION ® Reed width (max.) 1380 mm MÜGRIP MBJ8 1/1380 Nominal width (max.) 1346 mm Jacquard machine (sheeding device) SPE3 series Weave types Taff et Semi-Satin Satin Warp density (ends/cm) 54,6 88,82 109,2 Harness settings Label standards as per PZ 3003 Weft feeder Electronically controlled for up to 12 colours IRO Luna X3 Weft insert system Universal rapier for various yarn counts between 22 and 1400 dtex. Lightweight designed rapier head for outstanding long operational life Cross beam Rapier drive for smooth weft feeding with the unique vertical reed beat-up and for labels and high weft density fabrics optimised temple bar Machine control MLC machine control / network ready and MÜDATA® M series for the entire Label Weaving Machine machine monitoring and regulation Main drive VARISPEED – Energy-effi cient machine drive with programmable speed for labels and pictures with slit selvedges changes within the pattern design Fabric take-off drive VARIPICK – Energy-effi cient fabric take off drive for programmable weft density variations from 18 to 120 picks per cm within the pattern design Warp let-off drive Energy-effi cient and electronically controlled warp let-off drive with warp tension monitoring up to a warp beam diameter of 800 mm Selvedge formation TC2 cutting system for a good on loom selvedge quality starting from a minimum width of 6 mm. Due to the same electrical resistance an identical cutting temperature across the entire fabric width can be reached DIMENSIONS Width: 3940 mm (with thread feeder) 2955 mm (without thread feeder) Depth: 2030 mm Height: 3645 mm (machine) 3875 mm (room) Copyright @ 2019 by Jakob Müller AG Frick 5070 Frick Switzerland Fascination of Ribbons and Narrow Fabrics Printed in Italy. -

GIPE-020070-Contents.Pdf

SERVANTS Oll' INDIA SOCIETY'S LIBRARY, , POOHA ,. FOR INTERNAL CIRCULATION ITo be returned on or before the last date stamped below ~.5I1A y :g6 .... namtRJayaraG Gadgillibrary Ilm~ II11I a~ IUlium lUll mlill GIPE-PUN~-020070 X91(\'<\ 1 9. '2.. .N ,; \t i-{2--- ~co70 t Sf i ................... ~........... , .. REPORT OF TIlE. FACT .. FINDING COMMITTEE (HANDLOOM AND MILLS) PUBLISHEIl BY THE MANAGER OF PUBLICATIONS, DELHI PRINTED BY THE MANAGER, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA 'P'RESS, OALCUTTA 1942 List of Agents in India from whom Government of India Publications are available. AlIBOTTABAD-Bngllsh Book .Store. DHARWAB-Sbrl Sbankar Xarnataka Bbandara. AGRA- English Book Depot, Taj Road. PEROZEPORE-Bngllsh Book Depot. Indfan Army Book Depot, Dayalbagh. GW ALIOB-laln II; Bros., M....... lL 1I., Barala NatJooal Book H01Il!e, leomondl. HYDERABAD (DECCAN)- AHMEDABAD- Dom1n1on Book Conoeru, Hydergnda. Chandra Kant Cblman Lal Vom. Hyderabad Book Depot, Cbadergbat. H. L. College of Commerce C<H>perative Store, Ltd. lAIPUB-Garg Book Co., Trlpolla lIa&ar. AJ:MEBr-Bantblya &: Co., Ltd., Station Road. KARACIII- Aero Store&. AXOLA-BakshJ, K. G. xr. Standard BookataIL ALLAHABAD- • Ventral Book Depot, 44, lobDatongan\. KARACHI (SADAR)-Manager, SI.nd Governmm Depot and Record OlBce. X1tablstan. 17·A, City Road. Ram N araln Lal, I, Bank Road. LAHORE- Imperiall'1lblishlng Co., 99, RaIlway Road. Superintendent, Prlntlug and Statlouery, U. P. Kansll &; Co., K ....... N. C~ 9, Commerclal B. Wheeler &: Co., K ....... A. H. TbeMa1l. lIANGALORB CITY-Premier Book Co. llalhotra &: Co., ll....... U. P~ Poet Box No. II< lIARODA-East and West Book H01Il!e. )llnerva Book Shop, Auarllall Street. lIELGAUM-Model Book Depot, Xhade lIaaar. -

Pavendar Bharathidasan College of Arts and Science Department of Aparel and Fashion Technology

PAVENDAR BHARATHIDASAN COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF APAREL AND FASHION TECHNOLOGY SUBJECT : INDIAN TEXTILE, EMBROIDERY AND COSTUMES SUB CODE: 16SCCAF4 CLASS: II AFT UNIT-I ORIGIN OF COSTUMES PART-A 1. What is a human needs and development of clothing? Social scientists have been discussing for a long time as to what motivated human being to begin to wear clothes. The explanations most often by the experts are Protection, Modestly, Self-adornment. Each of these theories based the development of clothing on the desire to satisfy the human needs and wants. 2. What is a stronger than fashion? Modesty is based on tradition also because tradition is stronger than fashion and basic necessity. Traditional heavy garments of Arab women in extreme heat. The lack of clothing worn in extreme cold. These are classic examples of the importance of traditional values over desire for protective and modesty. 3. Define Beginning of costume. Since the first people put on the first pieces of clothing, what people wear has been in a constant change. Today changes are mostly related to style or fashion but for thousands of year’s change in clothes were made out of necessity. The first clues about clothes date back to around 75,000 to 100,000 years, No written records exist from those days. Painting , Cutting and Tattooing. 4. Draped garments of different civilization were called as follows: Draped fabric has another advantage of taking on a variety of shapes depending on how it is draped. Egyptians - Schenti Greeks - Chiton and himation Romans - Togas and stolas India - Saris and dhotis 5. -

Cover MAR APR FINAL.Cdr

SPINNING PEER REVIEWED The Process Dynamics of Egyptian Cotton G-86 with a Compact Spinning Machine Ibrahim A. Elhawary1* & Mohamed Y. Naeim2 1Alex Univercity, Egypt 2SETT-COR Spin Mill, Egypt Abstract In the present work, Giza 86 cotton (long staple cotton) was used to produce a different fine yarn with counts 14.7, 11.8, 10.5, 9.8, and 7.4tex on both of compact and ring spinning frames. The different yarn properties like, CVm%, tenacity, elongation, and hairiness were measured for both the two type of yarns. The relative yarn quality factor RYQF was calculated to detect the more suitable range of yarn counts for the compact spinning it was found that it ranges from 1.1 to 1.3 for range of yarn tex from 14.7 to 7.4 referring to the hairiness reduction it was found to be 31% for yam tex 9.8 the improvement in the yarn breaking elongation was 10%, the improvement in the yarn tenacity was 14%, while the reduction in the turns per meter in the compact spinning was 4%. And improvement in the yam mass variation was about 5%. On the other hand it was found that the improvement in the single compact yarn total imperfections was not statistically significant, But generally it was found that the yarn total imperfections of the single yarn were less for the compact spun yarns compared with the conventional ring spun yarns especially for the fine counts. 1. Introduction applied onto the yarn. Fibers are caught by the air Compact spinning is a new conversion for the ring current in the perforated drum soon after they leave spinning and it started to be applied in the Egyptian the nip point until they reach the nip point. -

Innovation in Weaving Napkin on the Kente Loom

Arts and Design Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-6061 (Paper) ISSN 2225-059X (Online) Vol.59, 2017 Innovation in Weaving Napkin on the Kente Loom *Gbadegbe Richard Selase¹ Vigbedor Divine¹ Agra Florence Emefa² Amankwa Joana² Gbetodeme Selorm ² 1.Department of Industrial Art, Ho Technical University, P. O. Box, 217, Ho, Volta Region, Ghana 2.Department of Fashion Design and Textiles, Ho Technical University, P.O. Box, 217 Ho, Volta Region, Ghana Abstract The Kente weaving industry in Ghana is a vibrant one. It is one of the foreign exchange earners of the country. Although meagre, the revenue generated by the Kente weaving industry in Ghana makes a significant impact on the citizenry. Apart from the economic value of Kente, the fabric plays a great role in the socio-cultural development of Ghana. Kente is worn during festive occasions such as durbars, outdooring of chiefs and newly born babies as well as marriage ceremonies. Kente is worn all-over the world to portray the Ghanaian culture. However, current developments where Kente fabrics are being pirated by the Chinese and other Nationals give a cause for concern. There is the need to move away from the usual blame games towards finding a lasting solution to this canker. One of the ways of addressing this issue is to pay much attention to quality and rebranding of the Kente weaving industry. It is for this and many other reasons that this topic which is aimed at modifying the Kente loom to weave napkin and other fabrics came to mind. Considering the technical nature of the topic, the descriptive (qualitative) method of research was adopted for the study. -

A1 Air-Jet Weaving Machine Brochure

A1 Flexible. Reliable. Efficient. Quality creates value WEAVING DORNIER A1 DORNIER A1: Productivity at maximum quality The DORNIER air-jet weaving machine A1 – a real all-round talent – offers innovative solutions for all challenges of weaving – today and tomorrow. Built on the proven technology of the DORNIER system family, the A1 convinces with a completely new electronic control system and an application-oriented main drive concept based on three different systems. Exceptionally wide range of application Whether operating with a simple cam motion, in combination with a Jacquard head of 12,000 hooks, a dobby with up to 16 heald frames or with the DORNIER EasyLeno® motion – the A1 is the perfect tool for the creative, economical and precise production of technical fabrics, home textiles and garment fabrics – in machine widths ranging from 150 up to 540 cm (59 inch up to 212 inch). A multitude of patented components, e. g. the DORNIER PIC® system with DORNIER ServoControl®-2 or the DORNIER PneumaTucker® guarantee a process security which is unparalleled in air-jet weaving. READY FOR THE The application spectrum of the A1 ranges from technical textiles such as lightest spinnaker silk, tightly woven airbags or conveyor belting to car- and airline seating Jacquard upholstery. Fabrics for garments of fine worsted or Jacquard damask fabric of Egyptian cotton, function and sportswear fabrics, home textiles for decoration and Jacquard table cloth with matching napkins in multiple widths, sheer window drapery – all these goods and many more can be reliably produced on the A1 with FUTURE excellent quality. “Quality creates value” - in the production of high value textiles for the automotive industry worldwide leading companies have relied on the DORNIER air-jet weaving machine for nearly 20 years because of its unparalleled flexibility and efficiency. -

United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 6,000,442 Busgen (45) Date of Patent: Dec

US006000442A United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 6,000,442 Busgen (45) Date of Patent: Dec. 14, 1999 54 WOVEN FABRIC HAVING A BULGING 5,336,538 8/1994 Kitamura ............................... 428/35.2 ZONE AND METHOD AND APPARATUS OF 5,441,798 8/1995 Nishimura et al. ..................... 428/229 5,477,890 12/1995 Krummheuer et al. 139/291 R FORMING SAME 5,651,395 7/1997 Graham et al. ......................... 139/390 5,685,347 11/1997 Graham et al. ......................... 139/390 76 Inventor: Alexander Busgen, Stahlstrasse 6, 5,707,711 1/1998 Kitamura ................................ 428/139 D-42281 Wuppertal, Germany 5,713,598 2/1998 Morita et al. ........................ 280/743.1 21 Appl. No.: 08/930,844 FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS 22 PCT Filed: Mar. 29, 1996 O 302 012 2/1989 European Pat. Off.. O 687 596 12/1995 European Pat. Off.. 86 PCT No.: PCT/EP96/01397 814429 6/1937 France ................................... 139/416 2 213 363 8/1974 France. S371 Date: Dec. 15, 1997 2 307 O64. 11/1976 France. 39 15085 11/1990 Germany. S 102(e) Date: Dec. 15, 1997 41 37 082 5/1993 Germany. 63-182446 7/1988 Japan ..................................... 139/418 87 PCT Pub. No.: WO96/31643 2 272 869 6/1994 United Kingdom. PCT Pub. Date: Oct. 10, 1996 OTHER PUBLICATIONS 30 Foreign Application Priority Data International Trade Bulletin, Gewebemusterung mit Fach Apr. 6, 1995 IDE Germany ........................... 195 12554 erwebblattern-eine alte und wieder neu entdeckte Technik, Oct. 31, 1995 DEI Germany ........................... 1954.0628 Feb. 1993, pp. 61-66, untranslated. 51) Int. Cl. -

Brandywine COTTON INDUSTRY", by Roy M. Boatman April, 1957

BRANDyWInE COTTON INDUSTRY", 1795-1865 by Roy M. Boatman April, 1957 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I THE ANTIQUITY OF COTTON MANUFACTURE Chapter II THE COTTON INDUSTRY ON THE BRANDYWINE BRECK'S MILL Chapter III HENRY CLAY MILL Chapter IV WALKER'S MILL Chapter V INDIVIDUAL COTTON MILLS ALONG THE BRANDY/TINE Chapter VI THE ROCKLAND MILLS Chapter VII THE KENTMERE AND ROCKFORD MILLS Chapter VIII THE BOROUGH MILL AND WOODEN KEG MILL Chapter IX POWER FOR THE BRANDYWINE COTTON MILLS Chapter X AUXILIARY INDUSTRIES Chapter XI COTTON MILLS ON NEIGHBORING STREAMS Chapter XII A SUMMARY OF THE COTTON INDUSTRY IN DELAWARE Chapter XIII CONCLUSIONS Appendixes A. Glossary of Terms B. List of Textile Patents in United States, 1791-180U C. "List of Mills on Brandywine and other creeks." "LIST OF DELAWARE MANUFACTORIES." D. Growth of Delaware and United States Cotton Mills, 1810-1880. E. Index The growth of the culture and manufacture of cotton in the United States constitutes the most striking feature of the industrial history of the last fifty years. Eighth Census—I860.1 The manufacture of cotton, on a home-industry basis, seems to have originated in Asia, probably in India, at a very early time. There are references in the law books of Manu as early as bOO B. C, but a much earlier date must be assumed since there are pictorial representations of Egyptian looms dating from 2,000 B. C. By the second century B. C. cotton culture had spread around the Mediterranean, from whence it slowly pene trated throughout Europe. The greatest impetus for its adoption by west erners came from the Crusaders. -

The Textile Museum, the Textile Museum, Yukari

THE TEXTILE MUSEUM, YUKARI Hello! And welcome to the Textile Museum, Yukari. The Textile Museum, Yukari brings Kiryu’s weaving history to life by providing looms which can actually be operated by visitors. Viewing the materials exhibited in the showcases and operating the machines themselves gives you the opportunity to follow in the footsteps of Kiryu’s textile history through the ages. If you wish to try the machines, please ask for assistance from one of the museum staff members. The museum preserves, maintains and displays ancient to modern weaving implements, and showcases the techniques for the cultivation of silkworms and production of silk yarn. In addition, the museum provides opportunities to experience firsthand the traditional techniques of indigo dyeing. Yukari also operates a school for dyeing and hand-weaving. Experienced artisans teach classes from introductory through advanced levels. The museum shop sells items of clothing, traditional crafts, weaving supplies and other popular souvenirs. Before beginning the tour, first close your eyes and try to imagine Kiryu during the heyday of the silk industry. From the end of the Edo Era, weaving looms and mass production techniques were quickly introduced in Japan. Not only did the domestic market for silk grow, but also, Japanese businessmen were eager to get a share of the growing international silk market. Kiryu silk weavers were astute in adapting local production techniques to meet the demands of overseas markets. They were also entrepreneurial in the creation of new weaving machinery, thrusting Kiryu to the forefront of the Japanese silk industry. By the turn of the 20 th century, the rhythmic sounds of looms eminating from weaving mills could be heard in every part of the city.