Unit 2 Inflection [Modo De Compatibilidad]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long and Short Adjunct Fronting in HPSG

Long and Short Adjunct Fronting in HPSG Takafumi Maekawa Department of Language and Linguistics University of Essex Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar Linguistic Modelling Laboratory, Institute for Parallel Processing, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Sofia, Held in Varna Stefan Muller¨ (Editor) 2006 CSLI Publications pages 212–227 http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/HPSG/2006 Maekawa, Takafumi. 2006. Long and Short Adjunct Fronting in HPSG. In Muller,¨ Stefan (Ed.), Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, Varna, 212–227. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. Abstract The purpose of this paper is to consider the proper treatment of short- and long-fronted adjuncts within HPSG. In the earlier HPSG analyses, a rigid link between linear order and constituent structure determines the linear position of such adjuncts in the sentence-initial position. This paper argues that there is a body of data which suggests that ad- junct fronting does not work as these approaches predict. It is then shown that linearisation-based HPSG can provide a fairly straightfor- ward account of the facts. 1 Introduction The purpose of this paper is to consider the proper treatment of short- and long-fronted adjuncts within HPSG. ∗ The following sentences are typical examples. (1) a. On Saturday , will Dana go to Spain? (Short-fronted adjunct) b. Yesterday I believe Kim left. (Long-fronted adjunct) In earlier HPSG analyses, a rigid link between linear order and constituent structure determines the linear position of such adverbials in the sen- tence-initial position. I will argue that there is a body of data which sug- gests that adjunct fronting does not work as these approaches predict. -

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

Noun Group and Verb Group Identification for Hindi

Noun Group and Verb Group Identification for Hindi Smriti Singh1, Om P. Damani2, Vaijayanthi M. Sarma2 (1) Insideview Technologies (India) Pvt. Ltd., Hyderabad (2) Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Mumbai, India [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT We present algorithms for identifying Hindi Noun Groups and Verb Groups in a given text by using morphotactical constraints and sequencing that apply to the constituents of these groups. We provide a detailed repertoire of the grammatical categories and their markers and an account of their arrangement. The main motivation behind this work on word group identification is to improve the Hindi POS Tagger’s performance by including strictly contextual rules. Our experiments show that the introduction of group identification rules results in improved accuracy of the tagger and in the resolution of several POS ambiguities. The analysis and implementation methods discussed here can be applied straightforwardly to other Indian languages. The linguistic features exploited here are drawn from a range of well-understood grammatical features and are not peculiar to Hindi alone. KEYWORDS : POS tagging, chunking, noun group, verb group. Proceedings of COLING 2012: Technical Papers, pages 2491–2506, COLING 2012, Mumbai, December 2012. 2491 1 Introduction Chunking (local word grouping) is often employed to reduce the computational effort at the level of parsing by assigning partial structure to a sentence. A typical chunk, as defined by Abney (1994:257) consists of a single content word surrounded by a constellation of function words, matching a fixed template. Chunks, in computational terms are considered the truncated versions of typical phrase-structure grammar phrases that do not include arguments or adjuncts (Grover and Tobin 2006). -

Understanding English Non-Count Nouns and Indefinite Articles

Understanding English non-count nouns and indefinite articles Takehiro Tsuchida Digital Hollywood University December 20, 2010 Introduction English nouns are said to be categorised into several groups according to certain criteria. Among such classifications is the division of count nouns and non-count nouns. While count nouns have such features as plural forms and ability to take the indefinite article a/an, non-count nouns are generally considered to be simply the opposite. The actual usage of nouns is, however, not so straightforward. Nouns which are usually regarded as uncountable sometimes take the indefinite article and it seems fairly difficult for even native speakers of English to expound the mechanism working in such cases. In particular, it seems to be fairly peculiar that the noun phrase (NP) whose head is the abstract „non-count‟ noun knowledge often takes the indefinite article a/an and makes such phrase as a good knowledge of Greek. The aim of this paper is to find out reasonable answers to the question of why these phrases occur in English grammar and thereby to help native speakers/teachers of English and non-native teachers alike to better instruct their students in 1 the complexity and profundity of English count/non-count dichotomy and actual usage of indefinite articles. This report will first examine the essential qualities of non-count nouns and indefinite articles by reviewing linguistic literature. Then, I shall conduct some research using the British National Corpus (BNC), focusing on statistical and semantic analyses, before finally certain conclusions based on both theoretical and actual observations are drawn. -

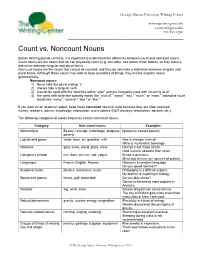

Count Vs Noncount Nouns

George Mason University Writing Center writingcenter.gmu.edu The [email protected] Writing Center 703.993.1200 Count vs. Noncount Nouns Before forming plurals correctly, it is important to understand the difference between count and noncount nouns. Count nouns are the nouns that we can physically count (e.g. one table, two tables, three tables), so they make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Noncount nouns are the nouns that cannot be counted, and they do not make a distinction between singular and plural forms. Although these nouns may refer to large quantities of things, they act like singular nouns grammatically. Noncount nouns: 1) Never take the plural ending “s” 2) Always take a singular verb 3) Cannot be used with the indefinite article “a/an” and are frequently used with no article at all 4) Are used with collective quantity words like “a lot of,” “some,” “any,” “much,” or “more,” instead of count words like “many,” “several,” “two,” or “few.” If you work on an academic paper, keep these noncount nouns in mind because they are often misused: money, research, advice, knowledge, information, and evidence (NOT moneys, researches, advices, etc.). The following categories of words frequently contain noncount nouns: Category Non-count nouns Examples Abstractions Beauty, revenge, knowledge, progress, Ignorance causes poverty. poverty Liquids and gases water, beer, air, gasoline, milk Gas is cheaper than oil. Wine is my favorite beverage. Materials gold, silver, wood, glass, sand He had a will made of iron. Gold is more valuable than silver. Categories of food rice, flour, cheese, salt, yogurt Bread is delicious. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

Bilingual Complex Verbs: So What’S New About Them? Author(S): Tridha Chatterjee Proceedings of the 38Th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (2014), Pp

Bilingual Complex Verbs: So what’s new about them? Author(s): Tridha Chatterjee Proceedings of the 38th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society (2014), pp. 47-62 General Session and Thematic Session on Language Contact Editors: Kayla Carpenter, Oana David, Florian Lionnet, Christine Sheil, Tammy Stark, Vivian Wauters Please contact BLS regarding any further use of this work. BLS retains copyright for both print and screen forms of the publication. BLS may be contacted via http://linguistics.berkeley.edu/bls/ . The Annual Proceedings of the Berkeley Linguistics Society is published online via eLanguage , the Linguistic Society of America's digital publishing platform. Bilingual Complex Verbs: So what’s new about them?1 TRIDHA CHATTERJEE University of Michigan, Ann Arbor Introduction In this paper I describe bilingual complex verb constructions in Bengali-English bilingual speech. Bilingual complex verbs have been shown to consist of two parts, the first element being either a verbal or nominal element from the non- native language of the bilingual speaker and the second element being a helping verb or dummy verb from the native language of the bilingual speaker. The verbal or nominal element from the non-native language provides semantics to the construction and the helping verb of the native language bears inflections of tense, person, number, aspect (Romaine 1986, Muysken 2000, Backus 1996, Annamalai 1971, 1989). I describe a type of Bengali-English bilingual complex verb which is different from the bilingual complex verbs that have been shown to occur in other codeswitched Indian varieties. I show that besides having a two-word complex verb, as has been shown in the literature so far, bilingual complex verbs of Bengali-English also have a three-part construction where the third element is a verb that adds to the meaning of these constructions and affects their aktionsart (aspectual properties). -

Syntactic Variation in English Quantified Noun Phrases with All, Whole, Both and Half

Syntactic variation in English quantified noun phrases with all, whole, both and half Acta Wexionensia Nr 38/2004 Humaniora Syntactic variation in English quantified noun phrases with all, whole, both and half Maria Estling Vannestål Växjö University Press Abstract Estling Vannestål, Maria, 2004. Syntactic variation in English quantified noun phrases with all, whole, both and half, Acta Wexionensia nr 38/2004. ISSN: 1404-4307, ISBN: 91-7636-406-2. Written in English. The overall aim of the present study is to investigate syntactic variation in certain Present-day English noun phrase types including the quantifiers all, whole, both and half (e.g. a half hour vs. half an hour). More specific research questions concerns the overall frequency distribution of the variants, how they are distrib- uted across regions and media and what linguistic factors influence the choice of variant. The study is based on corpus material comprising three newspapers from 1995 (The Independent, The New York Times and The Sydney Morning Herald) and two spoken corpora (the dialogue component of the BNC and the Longman Spoken American Corpus). The book presents a number of previously not discussed issues with respect to all, whole, both and half. The study of distribution shows that one form often predominated greatly over the other(s) and that there were several cases of re- gional variation. A number of linguistic factors further seem to be involved for each of the variables analysed, such as the syntactic function of the noun phrase and the presence of certain elements in the NP or its near co-text. -

The Syntax of Answers to Negative Yes/No-Questions in English Anders Holmberg Newcastle University

The syntax of answers to negative yes/no-questions in English Anders Holmberg Newcastle University 1. Introduction This paper will argue that answers to polar questions or yes/no-questions (YNQs) in English are elliptical expressions with basically the structure (1), where IP is identical to the LF of the IP of the question, containing a polarity variable with two possible values, affirmative or negative, which is assigned a value by the focused polarity expression. (1) yes/no Foc [IP ...x... ] The crucial data come from answers to negative questions. English turns out to have a fairly complicated system, with variation depending on which negation is used. The meaning of the answer yes in (2) is straightforward, affirming that John is coming. (2) Q(uestion): Isn’t John coming, too? A(nswer): Yes. (‘John is coming.’) In (3) (for speakers who accept this question as well formed), 1 the meaning of yes alone is indeterminate, and it is therefore not a felicitous answer in this context. The longer version is fine, affirming that John is coming. (3) Q: Isn’t John coming, either? A: a. #Yes. b. Yes, he is. In (4), there is variation regarding the interpretation of yes. Depending on the context it can be a confirmation of the negation in the question, meaning ‘John is not coming’. In other contexts it will be an infelicitous answer, as in (3). (4) Q: Is John not coming? A: a. Yes. (‘John is not coming.’) b. #Yes. In all three cases the (bare) answer no is unambiguous, meaning that John is not coming. -

Early Sensitivity to Telicity: the Role of the Count/Mass Distinction in Event Individuation

W O R K I N G P A P E R S I N L I N G U I S T I C S The notes and articles in this series are progress reports on work being carried on by students and faculty in the Department. Because these papers are not finished products, readers are asked not to cite from them without noting their preliminary nature. The authors welcome any comments and suggestions that readers might offer. Volume 41(4) 2010 (April) DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA HONOLULU 96822 An Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action Institution WORKING PAPERS IN LINGUISTICS: UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA, VOL. 41(4) DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS FACULTY 2010 Victoria B. Anderson Byron W. Bender (Emeritus) Benjamin Bergen Derek Bickerton (Emeritus) Robert A. Blust Robert L. Cheng (Adjunct) Kenneth W. Cook (Adjunct) Kamil Deen Patricia J. Donegan (Co-Graduate Chair) Katie K. Drager Emanuel J. Drechsel (Adjunct) Michael L. Forman (Emeritus) George W. Grace (Emeritus) John H. Haig (Adjunct) Roderick A. Jacobs (Emeritus) Paul Lassettre P. Gregory Lee Patricia A. Lee Howard P. McKaughan (Emeritus) William O’Grady (Chair) Yuko Otsuka Ann Marie Peters (Emeritus, Co-Graduate Chair) Kenneth L. Rehg Lawrence A. Reid (Emeritus) Amy J. Schafer Albert J. Schütz, (Emeritus, Editor) Ho Min Sohn (Adjunct) Nicholas Thieberger Laurence C. Thompson (Emeritus) ii EARLY SENSITIVITY TO TELICITY: THE ROLE OF THE COUNT/MASS DISTINCTION IN EVENT INDIVIDUATION YUKIE HARA1 This paper presents evidence that English-speaking children are sensitive to telicity based on the count/mass distinction of the object noun in verb phrases such as eat an apple (telic) vs. -

Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Semantic Countability1

Eun-Joo Kwak 55 Journal of Universal Language 15-2 September 2014, 55-76 Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Semantic Countability1 2 Eun-Joo Kwak Sejong University, Korea Abstract Countability and plurality (or singularity) are basically marked in syntax or morphology, and languages adopt different strategies in the mass-count distinction and number marking: plural marking, unmarked number marking, singularization, and different uses of classifiers. Diverse patterns of grammatical strategies are observed with cross-linguistic data in this study. Based on this, it is concluded that although countability is not solely determined by the semantic properties of nouns, it is much more affected by semantics than it appears. Moreover, semantic features of nouns are useful to account for apparent idiosyncratic behaviors of nouns and sentences. Keywords: countability, plurality, countability shift, individuation, animacy, classifier * This work is supported by the Sejong University Research Grant of 2013. Eun-Joo Kwak Department of English Language and Literature, Sejong University, Seoul, Korea Phone: +82-2-3408-3633; Email: [email protected] Received August 14, 2014; Revised September 3, 2014; Accepted September 10, 2014. 56 Cross-Linguistic Evidence for Semantic Countability 1. Introduction The state of affairs in the real world may be delivered in a different way depending on the grammatical properties of languages. Nominal countability makes part of grammatical differences cross-linguistically, marked in various ways: plural (or singular) morphemes for nouns or verbs, distinct uses of determiners, and the occurrences of classifiers. Apparently, countability and plurality are mainly marked in syntax and morphology, so they may be understood as having less connection to the semantic features of nouns. -

The Serial Verb Construction in Chinese: a Tenacious Myth and a Gordian Knot Waltraud Paul

The serial verb construction in Chinese: A tenacious myth and a Gordian knot Waltraud Paul To cite this version: Waltraud Paul. The serial verb construction in Chinese: A tenacious myth and a Gordian knot. Lin- guistic Review, De Gruyter, 2008, 25 (3-4), pp.367-411. 10.1515/TLIR.2008.011. halshs-01574253 HAL Id: halshs-01574253 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01574253 Submitted on 12 Aug 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The serial verb construction in Chinese: A tenacious myth and a Gordian knot1 WALTRAUD PAUL Abstract The term “construction” is not a label to be assigned randomly, but presup- poses a structural analysis with an associated set of syntactic and semantic properties. Based on this premise, the term “serial verb construction” (SVC) as currently used in Chinese linguistics will be shown to simply refer to any multi- verb surface string i.e,. to subsume different constructions. The synchronic consequence of this situation is that SVCs in Chinese linguistics are not com- mensurate with SVCs in, e.g., Niger-Congo languages, whence the futility at this stage to search for a “serialization parameter” deriving the differences between so-called “serializing” and “non-serializing” languages.