Searching for Morrison, Finding Morison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings 207

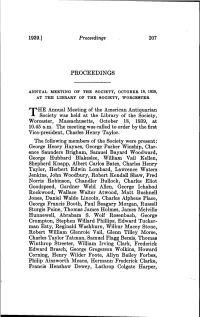

1939.] Proceedings 207 PROCEEDINGS ANNUAL MEETING OP THE SOCIETY, OCTOBER 18, 1939, AT THE LIBEARY OF THE SOCIETY, WORCESTER Annual Meeting of the Anierican Antiquarian -1 Society was held at the Library of the Society, Worcester, Massachusetts, October 18, 1939, at 10.45 a.m. The meeting was called to order by the first Vice-president, Charles Henry Taylor. The following members of the Society were present : George Henry Haynes, George Parker Winship, Clar- ence Saunders Brigham, Samuel Bayard Woodward, George Hubbard Blakeslee, William Vail Kellen, Shepherd Knapp, Albert Carlos Bates, Charles Henry Taylor, Herbert Edwin Lombard, Lawrence Waters Jenkins, John Woodbury, Robert Kendall Shaw, Fred Norris Robinson, Chandler BuUockj Charles Eliot Goodspeed, Gardner Weld Allen, George Ichabod Rockwood, Wallace Walter Atwood, Matt Bushneil Jones, Daniel Waldo Lincoln, Charles Alpheus Place, George Francis Booth, Paul Beagary Morgan, Russell Sturgis Paine, Thomas James Holmes, James Melville Hunnewell, Abraham S. Wolf Rosenbach, George Crompton, Stephen Willard Phillips, Edward Tucker- man Esty, Reginald Washburn, Wilbur Macey Stone, Robert William Glenroie Vail, Glenn Tilley Morse, Charles Taylor Tatman, Samuel Flagg Bemis, Thomas Winthrop Streeter, William Irving Clark, Frederick Edward Brasch, George Gregerson Wolkins, Howard Corning, Henry Wilder Foote, Allyn Bailey Forbes, Philip Ainsworth Means, Hermann Frederick Clarke, Francis Henshaw Dewey, Lathrop Colgate Harper, 208 American Antiquarian Society [Oct., Augustus Peabody Loring, Jr., James Duncan Phillips, Clifford Kenyon Shipton, Alexander Hamilton Bullock, Theron Johnson Damon, Albert White Rice, Fred- erick Lewis Weis, Donald McKay Frost, Harry- Andrew Wright. It was voted to dispense with the reading of the records of the last meeting. The report of the Council of the Society was presented by the Director, Mr. -

University Microfilms Copyright 1984 by Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. All

8404787 Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. BLACKS IN AMERICAN HISTORY TEXTBOOKS: A STUDY OF SELECTED THEMES IN POST-1900 COLLEGE LEVEL SURVEYS Middle Tennessee State University D.A. 1983 University Microfilms Internet ion elæ o N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 Copyright 1984 by Mitchell, Reavis Lee, Jr. All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. Problems encountered with this document have been identified here with a check mark V 1. Glossy photographs or pages. 2. Colored illustrations, paper or print_____ 3. Photographs with dark background_____ 4. Illustrations are poor copy______ 5. Pages with black marks, not original copy_ 6. Print shows through as there is text on both sides of page. 7. Indistinct, broken or small print on several pages______ 8. Print exceeds margin requirements______ 9. Tightly bound copy with print lost in spine______ 10. Computer printout pages with indistinct print. 11. Page(s)____________ lacking when material received, and not available from school or author. 12. Page(s) 18 seem to be missing in numbering only as text follows. 13. Two pages numbered _______iq . Text follows. 14. Curling and wrinkled pages______ 15. Other ________ University Microfilms International Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. BLACKS IN AMERICAN HISTORY TEXTBOOKS: A STUDY OF SELECTED THEMES IN POST-190 0 COLLEGE LEVEL SURVEYS Reavis Lee Mitchell, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of Middle Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Arts December, 1983 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Imperiology and Religion.Indd

10 FROM NATIONAL TERRITORIAL AUTONOMY TO INDEPENDENCE OF ESTONIA: THE WAR AND REVOLUTION 1 IN THE BALTIC REGION, 1914-1917 TIIT ROSENBERG INTRODUCTION Although the interactions between imperial management and nation-building, on which this part of the collection focuses, can be un- derstood from century-long perspectives, one should not ignore the fact that the Russian Empire fell apart not as a consequence of chronological contradictions between imperial and national principles, but rather in a peculiar conjuncture of events caused by World War I and the subse- quent revolutions.2 How were these long-term and conjuncture factors combined to affect Estonians’ quest for autonomy and independence? This chapter is devoted to this very question. From the beginning of the twentieth century, the three major politi- cal actors in the Baltic region, that is, the Baltic German elite, Estonian and Latvian nationals, and the Russian imperial authorities were involved in two serious problems of the region—the agrarian issue and regional self-government. In comparison with the agrarian question, to which policy-makers and intellectuals both in the imperial metropolis and the Baltic region began to pay attention as early as the 1840s, the question of regional self-government was relatively new for contemporaries, and 1 This article has been supported by the Estonian Science Foundation grant No 5710. 2 This point has been stressed by Andreas Kappeler, Russland als Vielvölkerreich: Entstehung, Geschichte, Zerfall (München, 1992), pp. 267-299; Ronald Grigor Suny, The Revenge of the Past. Nationalism, Revolution, and the Collapse of the Soviet Union, (Stanford, 1993), pp. -

List of Prime Ministers of Estonia

SNo Name Took office Left office Political party 1 Konstantin Päts 24-02 1918 26-11 1918 Rural League 2 Konstantin Päts 26-11 1918 08-05 1919 Rural League 3 Otto August Strandman 08-05 1919 18-11 1919 Estonian Labour Party 4 Jaan Tõnisson 18-11 1919 28-07 1920 Estonian People's Party 5 Ado Birk 28-07 1920 30-07 1920 Estonian People's Party 6 Jaan Tõnisson 30-07 1920 26-10 1920 Estonian People's Party 7 Ants Piip 26-10 1920 25-01 1921 Estonian Labour Party 8 Konstantin Päts 25-01 1921 21-11 1922 Farmers' Assemblies 9 Juhan Kukk 21-11 1922 02-08 1923 Estonian Labour Party 10 Konstantin Päts 02-08 1923 26-03 1924 Farmers' Assemblies 11 Friedrich Karl Akel 26-03 1924 16-12 1924 Christian People's Party 12 Jüri Jaakson 16-12 1924 15-12 1925 Estonian People's Party 13 Jaan Teemant 15-12 1925 23-07 1926 Farmers' Assemblies 14 Jaan Teemant 23-07 1926 04-03 1927 Farmers' Assemblies 15 Jaan Teemant 04-03 1927 09-12 1927 Farmers' Assemblies 16 Jaan Tõnisson 09-12 1927 04-121928 Estonian People's Party 17 August Rei 04-121928 09-07 1929 Estonian Socialist Workers' Party 18 Otto August Strandman 09-07 1929 12-02 1931 Estonian Labour Party 19 Konstantin Päts 12-02 1931 19-02 1932 Farmers' Assemblies 20 Jaan Teemant 19-02 1932 19-07 1932 Farmers' Assemblies 21 Karl August Einbund 19-07 1932 01-11 1932 Union of Settlers and Smallholders 22 Konstantin Päts 01-11 1932 18-05 1933 Union of Settlers and Smallholders 23 Jaan Tõnisson 18-05 1933 21-10 1933 National Centre Party 24 Konstantin Päts 21-10 1933 24-01 1934 Non-party 25 Konstantin Päts 24-01 1934 -

UAL-110 the Estonian Straits

UAL-110 The Estonian Straits Exceptions to the Strait Regime ofInnocent or Transit Passage By Alexander Lott BRILL NIJHOFF LEIDEN I BOSTON UAL-110 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Lott, Alexander, author. Title: The Estonian Straits: Exceptions to the Strait Regime of Innocent or Transit Passage / by Alexander Lott. Description: Leiden; Boston : Koninklijke Brill NV, 2018. I Series: International Straits of the World; Volwne 17 I Based on author's thesis ( doctoral - Tartu Olikool, 2017) issued under title: The Estonian Straits: Exceptions to the Strait Regime of Innocent or Transit Passage. I Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018001850 (print) I LCCN 201800201s (ebook) I ISBN 9789004365049 (e-book) I ISBN 9789004363861 (hardback: alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Straits-Baltic Sea, I Straits--Finland, Gulf of. I Straits--Riga, Gulf of (Latvia and Estonia), I Straits- Estonia, I Straits, I Innocent passage (Law of the sea) I Finland, Gulf of--Intemational status. I Riga, Gulf of (Latvia and Estonia)--Intemational status. Classification: LCC KZ3810 (ehook) I LCC KZ38IO .L68 2018 (print) I DOC 34I.4/48--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018001850 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: "Brill". See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 0924-4867 ISBN 978-90-04-36386-l (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-36504-9 ( e-book) Copyright 2018 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi, Brill Sense and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. -

20 American Antiquarian Society Lications of American Writers. One

20 American Antiquarian Society lications of American writers. One of his earliest catalogues was devoted to these early efforts and this has been followed at intervals by others in the same vein. This was, however, only one facet of his interests and the scholarly catalogues he published covering fiction, poetry, drama, and bibliographical works provide a valuable commentary on the history and the changing fashions of American book buying over four de- cades. The shop established on the premises at S West Forty- sixth Street in New York by Kohn and Papantonio shortly after the end of the war has become a mecca for bibliophiles from all over the United States and from foreign countries. It is not overstating the case to say that Kohn became the leading authority on first and important editions of American literature. He was an interested and active member of the American Antiquarian Society. The Society's incomparable holdings in American literature have been enriched by his counsel and his gifts. He will be sorely missed as a member, a friend, and a benefactor. C. Waller Barrett SAMUEL ELIOT MORISON Samuel Eliot Morison was born in Boston on July 9, 1887, and died there nearly eighty-nine years later on May 15, 1976. He lived most of his life at 44 Brimmer Street in Bos- ton. He graduated from Harvard in 1908, sharing a family tradition with, among others, several Samuel Eliots, Presi- dent Charles W. Eliot, Charles Eliot Norton, and Eking E. Morison. During his junior year he decided on teaching and writing history as an objective after graduation and in his twenty-fifth Harvard class report, he wrote: 'History is a hu- mane discipline that sharpens the intellect and broadens the mind, offers contacts with people, nations, and civilizations. -

Suicide Facts Oladeinde Is a Staff Writerall for Hands Suicide Is on the Rise Nationwide

A L p AN Stephen Murphy (left),of Boston, AMSAN Kevin Sitterson (center), of Roper, N.C., and AN Rick Martell,of Bronx, N.Y., await the launch of an F-14 Tomcat on the flight deckof USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71). e 4 24 e 6 e e Hidden secrets Operation Deliberate Force e e The holidays are a time for giving. USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN 71) e e proves what it is made of during one of e e Make time for your shipmates- it e e could be the gift of life. the biggest military operations in Europe e e since World War 11. e e e e 6 e e 28 e e Grab those Gifts e e Merchants say thanks to those in This duty’s notso tough e e uniform. Your ID card is worth more Nine-section duty is off to a great start e e e e than you may think. and gets rave reviews aboardUSS e e Anchorage (LSD 36). e e PAGE 17 e e 10 e e The right combination 30 e e e e Norfolk hospital corpsman does studio Sailors care,do their fair share e e time at night. Seabees from CBU420 build a Habitat e e e e for Humanity house in Jacksonville, Fla. e e 12 e e e e Rhyme tyme 36 e e Nautical rhymes bring the past to Smart ideas start here e e e e everyday life. See how many you Sailors learn the ropes and get off to a e e remember. -

Vera Poska-Grünthali Akadeemiline Karjäär Tartu Ülikooli Õigusteaduskonnas

Vera Poska-Grünthali akadeemiline karjäär Tartu Ülikooli õigusteaduskonnas MERIKE RISTIKIVI Sissejuhatus Vera Poska-Grünthal (1898–1986) on jätnud jälje Eesti ajalukku õige mitmel viisil: teda tuntakse eelkõige innuka naisliikumise aktivisti ning naiste ja laste õigustega tegelevate organisatsioonide asutaja- na. Samuti on tal silmapaistev panus Eesti õigusajaloos advokaa- dina esimese iseseisvusaja tsiviilseadustiku eelnõu perekonnaõigust käsitleva osa ettevalmistamisel. Käesolev artikkel peatub Vera Pos- ka-Grünthali teadustegevusel ja tööl esimese naislektorina Tartu Ülikooli õigusteaduskonnas. Vera Poska-Grünthali juuraõpingute aeg peegeldab hästi 20. sa- jandi alguses aset leidnud muudatusi: tsaariajal gümnaasiumi lõpe- tanuna suundus ta esmalt õppima Peterburisse, sest toonases Tartu ülikoolis said naised õppida ainult vabakuulajatena.1 Kui iseseisvu- nud Eestis alustas 1920. aastal tööd õigusteaduskond, astus Vera 1 Naiste ülikoolis õppimise ja haridusvõimaluste kohta enne 1918 lähemalt vt: Lea Leppik, „Naiste haridusvõimalustest Vene impeeriumis enne 1905. aastat“, Tartu Ülikooli ajaloo küsimusi, XXXV (Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus, 2006), 34–52; Sirje Tamul, koost, Vita academica, vita feminea. Artiklite kogumik (Tartu: Tartu Ülikooli Kirjastus, 1999); Heide W. Whelan, „The Debate on Women’s Education in the Baltic Provinces, 1850 to 1905“, Gert von Pistohlkors, Andris Plakans, Paul Kaegbein, koost, Population Shifts and Social Change in Russia’s Baltic Provinces (Lüneburg: Institut Nordostdeutsches Kulturwerk, 1995). 134 Tartu -

Estonian Academy of Sciences Yearbook 2018 XXIV

Facta non solum verba ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES YEARBOOK FACTS AND FIGURES ANNALES ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM ESTONICAE XXIV (51) 2018 TALLINN 2019 This book was compiled by: Jaak Järv (editor-in-chief) Editorial team: Siiri Jakobson, Ebe Pilt, Marika Pärn, Tiina Rahkama, Ülle Raud, Ülle Sirk Translator: Kaija Viitpoom Layout: Erje Hakman Photos: Annika Haas p. 30, 31, 48, Reti Kokk p. 12, 41, 42, 45, 46, 47, 49, 52, 53, Janis Salins p. 33. The rest of the photos are from the archive of the Academy. Thanks to all authos for their contributions: Jaak Aaviksoo, Agnes Aljas, Madis Arukask, Villem Aruoja, Toomas Asser, Jüri Engelbrecht, Arvi Hamburg, Sirje Helme, Marin Jänes, Jelena Kallas, Marko Kass, Meelis Kitsing, Mati Koppel, Kerri Kotta, Urmas Kõljalg, Jakob Kübarsepp, Maris Laan, Marju Luts-Sootak, Märt Läänemets, Olga Mazina, Killu Mei, Andres Metspalu, Leo Mõtus, Peeter Müürsepp, Ülo Niine, Jüri Plado, Katre Pärn, Anu Reinart, Kaido Reivelt, Andrus Ristkok, Ave Soeorg, Tarmo Soomere, Külliki Steinberg, Evelin Tamm, Urmas Tartes, Jaana Tõnisson, Marja Unt, Tiit Vaasma, Rein Vaikmäe, Urmas Varblane, Eero Vasar Printed in Priting House Paar ISSN 1406-1503 (printed version) © EESTI TEADUSTE AKADEEMIA ISSN 2674-2446 (web version) CONTENTS FOREWORD ...........................................................................................................................................5 CHRONICLE 2018 ..................................................................................................................................7 MEMBERSHIP -

Jefferson's Failed Anti-Slavery Priviso of 1784 and the Nascence of Free Soil Constitutionalism

MERKEL_FINAL 4/3/2008 9:41:47 AM Jefferson’s Failed Anti-Slavery Proviso of 1784 and the Nascence of Free Soil Constitutionalism William G. Merkel∗ ABSTRACT Despite his severe racism and inextricable personal commit- ments to slavery, Thomas Jefferson made profoundly significant con- tributions to the rise of anti-slavery constitutionalism. This Article examines the narrowly defeated anti-slavery plank in the Territorial Governance Act drafted by Jefferson and ratified by Congress in 1784. The provision would have prohibited slavery in all new states carved out of the western territories ceded to the national government estab- lished under the Articles of Confederation. The Act set out the prin- ciple that new states would be admitted to the Union on equal terms with existing members, and provided the blueprint for the Republi- can Guarantee Clause and prohibitions against titles of nobility in the United States Constitution of 1788. The defeated anti-slavery plank inspired the anti-slavery proviso successfully passed into law with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. Unlike that Ordinance’s famous anti- slavery clause, Jefferson’s defeated provision would have applied south as well as north of the Ohio River. ∗ Associate Professor of Law, Washburn University; D. Phil., University of Ox- ford, (History); J.D., Columbia University. Thanks to Sarah Barringer Gordon, Thomas Grey, and Larry Kramer for insightful comment and critique at the Yale/Stanford Junior Faculty Forum in June 2006. The paper benefited greatly from probing questions by members of the University of Kansas and Washburn Law facul- ties at faculty lunches. Colin Bonwick, Richard Carwardine, Michael Dorf, Daniel W. -

Above the World: William Jennings Bryan's View of the American

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Above the World: William Jennings Bryan’s View of the American Nation in International Affairs Full Citation: Arthur Bud Ogle, “Above the World: William Jennings Bryan’s View of the American Nation in International Affairs,” Nebraska History 61 (1980): 153-171. URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/1980-2-Bryan_Intl_Affairs.pdf Date: 2/17/2010 Article Summary: One of the major elements in Bryan’s intellectual and political life has been largely ignored by both critics and admirers of William Jennings Bryan: his vital patriotism and nationalism. By clarifying Bryan’s Americanism, the author illuminates an essential element in his political philosophy and the consistent reason behind his foreign policy. Domestically Bryan thought the United States could be a unified monolithic community. Internationally he thought America still dominated her hemisphere and could, by sheer energy and purity of commitment, re-order the world. Bryan failed to understand that his vision of the American national was unrealizable. The America he believed in was totally vulnerable to domestic intolerance and international arrogance. -

Bernard Bailyn, W

Acad. Quest. (2021) 34.1 10.51845/34s.1.24 DOI 10.51845/34s.1.24 Reviews He won the Pulitzer Prize in history twice: in 1968 for The Ideological Illuminating History: A Retrospective Origins of the American Revolution of Seven Decades, Bernard Bailyn, W. and in 1987 for Voyagers to the West, W. Norton & Company, 2020, 270 pp., one of several volumes he devoted $28.95 hardbound. to the rising field of Atlantic history. Though Bailyn illuminated better than most scholars the contours of Bernard Bailyn: An seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Historian to Learn From American history, his final book hints at his growing concern about the Robert L. Paquette rampant opportunism and pernicious theoretical faddishness that was corrupting the discipline he loved and to which he had committed his Bernard Bailyn died at the age professional life. of ninety-seven, four months after Illuminating History consists of publication of this captivating curio five chapters. Each serves as kind of of a book, part autobiography, part a scenic overlook during episodes meditation, part history, and part of a lengthy intellectual journey. historiography. Once discharged At each stop, Bailyn brings to the from the army at the end of World fore little known documents or an War II and settled into the discipline obscure person’s life to open up of history at Harvard University, views into a larger, more complicated Bailyn undertook an ambitious quest universe, which he had tackled to understand nothing less than with greater depth and detail in the structures, forces, and ideas previously published books and that ushered in the modern world.