20Th - Century Poetry in Irish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daddy, Daddy/Mammy, Mammy: Sylvia Plath and Thomas Kinsella Andrew Browne, National University of Ireland, Galway

Plath Profiles 50 Daddy, Daddy/Mammy, Mammy: Sylvia Plath and Thomas Kinsella Andrew Browne, National University of Ireland, Galway In his memoir The Kick: a Life among Writers , Richard Murphy recalls Thomas and Eleanor Kinsella joining Sylvia Plath, Ted Hughes and himself in Ireland (Murphy, 226-27). Kinsella softens any profound inferences from this meeting in a 1989 interview with Dennis O’Driscoll. In response to O’Driscoll’s comment on the ‘torrid atmosphere’ of the meeting Kinsella says: It doesn’t strike me in retrospect as having been very torrid. It was just a couple of people having trouble. It didn’t have the heavy implications that her subsequent suicide gave it. We went out fishing and, as far as I am concerned, those fish coming up on the hooks were the exciting thing. But we did enjoy her company, and we did drive her back to Dublin; and that’s as much as I remember of it. (O’Driscoll, 59) This remark does not support any spectacular influence between Kinsella and Plath, and this critic is in no position to infer a direct impact upon Kinsella’s work from Plath’s, yet this essay will show connections between Plath’s and Kinsella’s poetry in their psychological imagery. I will also highlight differences while making certain assumptions about the way images of the masculine and feminine are interrogated, and how they impact their personal lives. There is a significant influence from Lowell’s work and there are resonances between the confessional style and parts of Kinsella’s oeuvre. -

Fall 2003 Archipelago

archipelago An International Journal of Literature, the Arts, and Opinion www.archipelago.org Vol. 7, No. 3 Fall 2003 AN LEABHAR MÒR / THE GREAT BOOK OF GAELIC An Exhibiton : Twenty-two Irish and Scottish Gaelic Poems, Translations and Artworks, with Essays and Recitations Fiction: PATRICIA SARRAFIAN WARD “Alaine played soccer with the refugees, she traded bullets and shrapnel around the neighborhood . .” from THE BULLET COLLECTION Poem: ELEANOR ROSS TAYLOR Our Lives Are Rounded With A Sleep Reflection: ANANT KUMAR The Mosques on the Banks of the Ganges: Apart or Together? tr. from the German by Rajendra Prasad Jain Photojournalism: PETER TURNLEY Seeing Another War in Iraq in 2003 and The Unseen Gulf War : Photographs Audio report on-line by Peter Turnley Endnotes: KATHERINE McNAMARA The Only God Is the God of War : On BLOOD MERIDIAN, an American myth printed from our pdf edition archipelago www.archipelago.org CONTENTS AN LEABHAR MÒR / THE GREAT BOOK OF GAELIC 4 Introduction : Malcolm Maclean 5 On Contemporary Irish Poetry : Theo Dorgan 9 Is Scith Mo Chrob Ón Scríbainn ‘My hand is weary with writing’ 13 Claochló / Transfigured 15 Bean Dubh a’ Caoidh a Fir Chaidh a Mharbhadh / A Black Woman Mourns Her Husband Killed by the Police 17 M’anam do sgar riomsa a-raoir / On the Death of His Wife 21 Bean Torrach, fa Tuar Broide / A Child Born in Prison 25 An Tuagh / The Axe 30 Dan do Scátach / A Poem to Scátach 34 Èistibh a Luchd An Tighe-Se / Listen People Of This House 38 Maireann an t-Seanmhuintir / The Old Live On 40 Na thàinig anns a’ churach -

Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Senior Scholar Papers Student Research 1998 From Image to Image Maker: Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition Rebecca Troeger Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/seniorscholars Colby College theses are protected by copyright. They may be viewed or downloaded from this site for the purposes of research and scholarship. Reproduction or distribution for commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the author. Recommended Citation Troeger, Rebecca, "From Image to Image Maker: Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition" (1998). Senior Scholar Papers. Paper 548. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/seniorscholars/548 This Senior Scholars Paper (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Scholar Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. Rebecca Troeger From Image to Image Maker: Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition • The Irish literary tradition has always been inextricably bound with the idea of image-making. Because of ueland's historical status as a colony, and of Irish people's status as dispossessed of their land, it has been a crucial necessity for Irish writers to establish a sense of unique national identity. Since the nationalist movement that lead to the formation of the Insh Free State in 1922 and the concurrent Celtic Literary Re\'ivaJ, in which writers like Yeats, O'Casey, and Synge shaped a nationalist consciousness based upon a mythology that was drawn only partially from actual historical documents, the image of Nation a. -

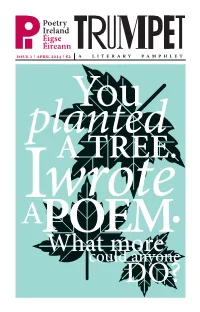

Issue 6 April 2017 a Literary Pamphlet €4

issue 6 april 2017 a literary pamphlet €4 —1— Denaturation Jean Bleakney from selected poems (templar poetry, 2016) INTO FLIGHTSPOETRY Taken on its own, the fickle doorbell has no particular score to settle (a reluctant clapper? an ill-at-ease dome?) were it not part of a whole syndrome: the stubborn gate; flaking paint; cotoneaster camouflaging the house-number. Which is not to say the occupant doesn’t have (to hand) lubricant, secateurs, paint-scraper, an up-to-date shade card known by heart. It’s all part of the same deferral that leaves hanging baskets vulnerable; although, according to a botanist, for most plants, short-term wilt is really a protective mechanism. But surely every biological system has its limits? There’s no going back for egg white once it’s hit the fat. Yet, some people seem determined to stretch, to redefine those limits. Why are they so inclined? —2— INTO FLIGHTSPOETRY Taken on its own, the fickle doorbell has no particular score to settle by Thomas McCarthy (a reluctant clapper? an ill-at-ease dome?) were it not part of a whole syndrome: the stubborn gate; flaking paint; cotoneaster Tara Bergin This is Yarrow camouflaging the house-number. carcanet press, 2013 Which is not to say the occupant doesn’t have (to hand) lubricant, secateurs, paint-scraper, an up-to-date Jane Clarke The River shade card known by heart. bloodaxe books, 2015 It’s all part of the same deferral that leaves hanging baskets vulnerable; Adam Crothers Several Deer although, according to a botanist, carcanet press, 2016 for most plants, short-term wilt is really a protective mechanism. -

Cork World Book Fest

CORK WORLD BOOK FEST Mon 23 - Sat 28 April 2018 City Library - Grand Parade Triskel Christchurch BOOKING INFORMATION Cork City Library Triskel Christchurch Library events are free of charge In Person: Triskel Box Office and tickets are not required. By phone: 021 4272022 Where pre-booking is specified 24hr Online Booking: you can do so, www.triskelartscentre.ie In person: Reception desk By Phone: 021-4924900 follow us on social media Cork World Book Festival @ WorldBookFest CORK WORLD BOOK FEST 2018 It is hard to believe that it is 13 years The Cork World Book Fest is a joint since the first Cork World Book Fest. production of the City Libraries and Triskel When we put ‘World’ in the title in Christchurch, with the active support of 2005, it was an aspiration. Now Cork the Munster Literature Centre. BOOKING INFORMATION is a vibrant intercultural city, and the This year the Fest will take place in the Intercultural City is one of the key City Library, in the Grand Parade plaza strands of this year’s Fest. outside the Library, in the adjoining Bishop Lucey Park and Triskel The 2018 Fest is the 14th edition of a Christchurch, and on the streets (and festival which continues to grow in some of the cafés) of Cork (see Fired! on range and breadth, and which, we page 14). hope, gets more interesting by the year. We hope you enjoy the 14th Cork World Book Fest – it is you, the audience, who ensure its continued success each year. The Fest has always sought to combine readings by world class writers in a variety of settings with a cultural streetfair: book stalls, music, street entertainment, the The Cork World Book Fest spoken word, and more. -

What More Could Anyone Do?

issue 1 / april 2014 / €2 a literary pamphlet You planted A TREE. Iwrote APOEM. Whatcould more anyone DO? My father, the least happy man I have known. His face retained the pallor The of those who work underground: the lost years in Brooklyn listening to a subway shudder the earth. Cage But a traditional Irishman who (released from his grille John Montague in the Clark Street IRT) drank neat whiskey until from new collected poems he reached the only element (the gallery press, 2012) he felt at home in any longer: brute oblivion. And yet picked himself up, most mornings, to march down the street extending his smile to all sides of the good, (all-white) neighbourhood belled by St Teresa's church. When he came back we walked together across fields of Garvaghey to see hawthorn on the summer hedges, as though he had never left; a bend in the road which still sheltered primroses. But we did not smile in the shared complicity of a dream, for when weary Odysseus returns Telemachus should leave. Often as I descend into subway or underground I see his bald head behind the bars of the small booth; the mark of an old car accident beating on his ghostly forehead. —2— 21 74 Sc ience and W onder by Richard Hayes Iggy McGovern A Mystic Dream of 4 quaternia press, €11.50 Iggy McGovern’s A Mystic Dream of 4 is an ambitious sonnet sequence based on the life of mathematician William Rowan Hamilton. Hamilton was one of the foremost scientists of his day, was appointed the Chair of Astronomy in Dublin University (Trinity College) while in the final year of his degree, and was knighted in 1835. -

The 'Nothing-Could-Be-Simpler Line': Form in Contemporary Irish Poetry

The 'nothing-could-be-simpler line': Form in Contemporary Irish Poetry Brearton, F. (2012). The 'nothing-could-be-simpler line': Form in Contemporary Irish Poetry. In F. Brearton, & A. Gillis (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Modern Irish Poetry (pp. 629-647). Oxford University Press. Published in: The Oxford Handbook of Modern Irish Poetry Document Version: Early version, also known as pre-print Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:26. Sep. 2021 OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST PROOF, 04/19/2012, SPi c h a p t e r 3 8 ‘the nothing-could- be-simpler line’: form in contemporary irish poetry f r a n b r e a r t o n I I n ‘ Th e Irish Effl orescence’, Justin Quinn argues in relation to a new generation of poets from Ireland (David Wheatley, Conor O’Callaghan, Vona Groarke, Sinéad Morrissey, and Caitríona O’Reilly among them) that while: Northern Irish poetry, in both the fi rst and second waves, is preoccupied with the binary opposition of Ireland and England . -

Irish Studies Around the World – 2020

Estudios Irlandeses, Issue 16, 2021, pp. 238-283 https://doi.org/10.24162/EI2021-10080 _________________________________________________________________________AEDEI IRISH STUDIES AROUND THE WORLD – 2020 Maureen O’Connor (ed.) Copyright (c) 2021 by the authors. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged for access. Introduction Maureen O’Connor ............................................................................................................... 240 Cultural Memory in Seamus Heaney’s Late Work Joanne Piavanini Charles Armstrong ................................................................................................................ 243 Fine Meshwork: Philip Roth, Edna O’Brien, and Jewish-Irish Literature Dan O’Brien George Bornstein .................................................................................................................. 247 Irish Women Writers at the Turn of the 20th Century: Alternative Histories, New Narratives Edited by Kathryn Laing and Sinéad Mooney Deirdre F. Brady ..................................................................................................................... 250 English Language Poets in University College Cork, 1970-1980 Clíona Ní Ríordáin Lucy Collins ........................................................................................................................ 253 The Theater and Films of Conor McPherson: Conspicuous Communities Eamon -

The Early Work of Austin Clarke the Early Work (1916-1938)

THE EARLY WORK OF AUSTIN CLARKE THE EARLY WORK (1916-1938) OF AUSTIN CLARKE By MAURICE RIORDAN, M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University March 1981 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (1981) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (English) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: The Early Work (1916-1938) of Austin Clarke. AUTHOR: Maurice Riordan, B.A. (Cork) M.A. (Cork) SUPERVISOR: Dr. Brian John NUMBER OF Fll.GES: vi, 275 ii ABSTRACT Austin Clarke dedicated himself to the ideal of an independent Irish literature in English. This dedication had two principal consequences for his work: he developed a poetic style appropriate to expressing the Irish imagination, and he found inspiration in the matter of Ireland, in hex mythology and folklore, in her literary, artistic and __ religious traditions, and in the daily life of modern Ireland. The basic orientation of Clarke's work determines the twofold purpose of this thesis. It seeks to provide a clarifying background for his poetry, drama and fiction up to 1938; and, in examining the texts in their prope.r context, it seeks to reveal the permanent and universal aspects of his achievement. Clarke's early development in response to the shaping influence of the Irish Revival is examined in the opening chapter. His initial interest in heroic saga is considered, but, principally, the focus is on his effort to establish stylistic links between the Anglo-Irish and the Gaelic traditions, an effort that is seen to culminate with his adoption of assonantal verse as an essential element in his poetic technique. -

“Am I Not of Those Who Reared / the Banner of Old Ireland High?” Triumphalism, Nationalism and Conflicted Identities in Francis Ledwidge’S War Poetry

Romp /1 “Am I not of those who reared / The banner of old Ireland high?” Triumphalism, nationalism and conflicted identities in Francis Ledwidge’s war poetry. Bachelor Thesis Charlotte Romp Supervisor: dr. R. H. van den Beuken 15 June 2017 Engelse Taal en Cultuur Radboud University Nijmegen Romp /2 Abstract This research will answer the question: in what ways does the poetry written by Francis Ledwidge in the wake of the Easter Rising reflect a changing stance on his role as an Irish soldier in the First World War? Guy Beiner’s notion of triumphalist memory of trauma will be employed in order to analyse this. Ledwidge’s status as a war poet will also be examined by applying Terry Phillips’ definition of war poetry. By remembering the Irish soldiers who decided to fight in the First World War, new light will be shed on a period in Irish history that has hitherto been subjected to national amnesia. This will lead to more complete and inclusive Irish identities. This thesis will argue that Ledwidge’s sentiments with regards to the war changed multiple times during the last year of his life. He is, arguably, an embodiment of the conflicting loyalties and tensions in Ireland at the time of the Easter Rising. Key words: Francis Ledwidge, Easter Rising, First World War, Ireland, Triumphalism, war poetry, loss, homesickness Romp /3 Table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 Chapter 1 History and Theory ................................................................................................... -

Oxford Brookes Poetry Centre Collection

LIBRARY Oxford Brookes Poetry Centre Collection This collection was set up in collaboration with the Oxford Brookes Poetry Centre to promote contemporary poetry from the UK, Ireland, United States and beyond. It comprises books that have been shortlisted for 6 poetry prizes from the UK, Ireland, USA and beyond. The books are housed in the Headington Library (Level 4, Zone D) and they can all be borrowed. Find out more about the collection and the Oxford Brookes Poetry Centre on our web pages TS Eliot Prize for Poetry The TS Eliot Prize for Poetry is presented annually by The Poetry Book Society. The Collection covers the books shortlisted for the prize since 2012. TS Eliot Prize shortlist 2018 Winner: Hannah Sullivan, Three poems Phoebe Power, Shrines of Upper Austria Tracy K. Smith, Wade in the water + Ailbhe Darcy – Insistence Terrance Hayes – American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassins Zaffar Kunial – Us Nick Laird – Feel Free Fiona Moore – The Distal Point Sean O'Brien – Europa Richard Scott – Soho TS Eliot Prize shortlist 2017 Winner: Ocean Vuong, Night sky with exit wounds Tara Bergin, The tragic death of Eleanor Marx Caroline Bird, In these days of prohibition Douglas Dunn, The noise of a fly Leontia Flynn, The radio Roddy Lumsden, So glad I'm me Robert Minhinnick, Diary of the last man Michael Symmons Roberts, Mancunia Jacqueline Saphra, All my mad mothers James Sheard, The abandoned settlements TS Eliot Prize shortlist 2016 Winner: Jacob Polley, Jackself Rachael Boast, Void Studies Vahni Capildeo, Measures of Expatriation Ian Duhig, The Blind Roadmaker J O Morgan, Interference Pattern WWW.BROOKES.AC.UK/LIBRARY Bernard O’Donoghue, The Seasons of Cullen Church Alice Oswald, Falling Awake Denise Riley, Say Something Back Ruby Robinson, Every Little Sound Katharine Towers, The Remedies TS Eliot Prize shortlist 2015 Winner: Sarah Howe, Loop of Jade Mark Doty, Deep Lane Tracey Herd, Not in this World Selima Hill, Jutland Tim Liardet, The World before Snow Les A. -

Eoghán Rua Ó Suilleabháin: a True Exponent of the Bardic Legacy

134 Eoghán Rua Ó Suilleabháin: A True Exponent of the Bardic Legacy endowed university. The Bardic schools and the monastic schools were the universities of their day; they bestowed privileges and Barra Ó Donnabháin Symposium: status on their students and teachers, much as the modern university awards degrees and titles to recipients to practice certain professions. There are few descriptions of the structure and operation of Eoghán Rua Ó Suilleabháin: A the Bardic schools, but an account contained in the early eighteenth century Memoirs of the Marquis of Clanricarde claims that admission True Exponent of the Bardic WR %DUGLF VFKRROV ZDV FRQÀQHG WR WKRVH ZKR ZHUH GHVFHQGHG from poets and had within their tribe “The Reputation” for poetic Legacy OHDUQLQJ DQG WDOHQW ´7KH TXDOLÀFDWLRQV ÀUVW UHTXLUHG VLF ZHUH Pádraig Ó Cearúill reading well, writing the Mother-tongue, and a strong memory,” according to Clanricarde. With regard to the location of the schools, he asserts that it was necessary that the place should “be in the solitary access of a garden” or “within a set or enclosure far out of the reach of any noise.” The structure containing the Bardic school, we are told, “was snug, low, hot and beds in it at convenient distances, each within a small apartment without much furniture of any kind, save only a table, some seats and a conveniency for he poetry of Eoghan Rua Ó Súilleabháin (1748-1784)— cloaths (sic) to hang upon. No windows to let in the day, nor any Tregarded as one of Ireland’s great eighteenth century light at all used but that of candles” according to Clanricarde,2 poets—has endured because of it’s extraordinary metrical whose account is given credence by Bergin3 and Corkery.