The 'Nothing-Could-Be-Simpler Line': Form in Contemporary Irish Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daddy, Daddy/Mammy, Mammy: Sylvia Plath and Thomas Kinsella Andrew Browne, National University of Ireland, Galway

Plath Profiles 50 Daddy, Daddy/Mammy, Mammy: Sylvia Plath and Thomas Kinsella Andrew Browne, National University of Ireland, Galway In his memoir The Kick: a Life among Writers , Richard Murphy recalls Thomas and Eleanor Kinsella joining Sylvia Plath, Ted Hughes and himself in Ireland (Murphy, 226-27). Kinsella softens any profound inferences from this meeting in a 1989 interview with Dennis O’Driscoll. In response to O’Driscoll’s comment on the ‘torrid atmosphere’ of the meeting Kinsella says: It doesn’t strike me in retrospect as having been very torrid. It was just a couple of people having trouble. It didn’t have the heavy implications that her subsequent suicide gave it. We went out fishing and, as far as I am concerned, those fish coming up on the hooks were the exciting thing. But we did enjoy her company, and we did drive her back to Dublin; and that’s as much as I remember of it. (O’Driscoll, 59) This remark does not support any spectacular influence between Kinsella and Plath, and this critic is in no position to infer a direct impact upon Kinsella’s work from Plath’s, yet this essay will show connections between Plath’s and Kinsella’s poetry in their psychological imagery. I will also highlight differences while making certain assumptions about the way images of the masculine and feminine are interrogated, and how they impact their personal lives. There is a significant influence from Lowell’s work and there are resonances between the confessional style and parts of Kinsella’s oeuvre. -

The Gallery Press

The Gallery Press The Gallery Press’s contribu - The Gallery Press has an unrivalled track record in publishing the tion to the cultural life of this first and subsequent collections of poems by now established Irish country is ines timable. The title poets such as Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Eamon Grennan, ‘national treasure’ is these days Michael Coady, Dermot Healy, Frank McGuinness and Peter conferred, facetiously for the Sirr . It has fostered whole generations of younger poets it pub - most part, on almost any old lished first including Ciaran Berry, Tom French, Alan Gillis, thing — person or institution — Vona Groarke, Conor O’Callaghan, John McAuliffe, Kerry but The Gallery Press truly is an Hardie, David Wheatley, Michelle O’Sullivan and Andrew enterprise to be treasured by the Jamison . It has also published seminal career-establishing titles nation. by Ciaran Carson, Paula Meehan, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, — John Banville Justin Quinn, Seán Lysaght and Gerald Dawe . The Press has published books by Seamus Heaney, Paul Muldoon and John Banville and repatriated authors such as Brian Friel, Derek Peter Fallon’s Gallery Press is the Mahon and Medbh McGuckian who previously turned to living fulcrum around which the London and Oxford as a publishing outlet. swarm ing life of contemporary Irish poetry rotates. Fallon’s is a Gallery publishes the work of Ireland’s leading women poets truly extraordinary Irish life, and and playwrights including Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Nuala Ní it goes on still, unabated. Dhomhnaill, Medbh McGuckian, Michelle O’Sullivan, Sara — Thomas McCarthy, Irish Berkeley Tolchin, Vona Groarke, Ailbhe Ní Ghearbhuigh, Literary Supplement Aifric MacAodha and Marina Carr . -

Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Senior Scholar Papers Student Research 1998 From Image to Image Maker: Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition Rebecca Troeger Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/seniorscholars Colby College theses are protected by copyright. They may be viewed or downloaded from this site for the purposes of research and scholarship. Reproduction or distribution for commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the author. Recommended Citation Troeger, Rebecca, "From Image to Image Maker: Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition" (1998). Senior Scholar Papers. Paper 548. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/seniorscholars/548 This Senior Scholars Paper (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Scholar Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. Rebecca Troeger From Image to Image Maker: Contemporary Irish Women Poets and the National Tradition • The Irish literary tradition has always been inextricably bound with the idea of image-making. Because of ueland's historical status as a colony, and of Irish people's status as dispossessed of their land, it has been a crucial necessity for Irish writers to establish a sense of unique national identity. Since the nationalist movement that lead to the formation of the Insh Free State in 1922 and the concurrent Celtic Literary Re\'ivaJ, in which writers like Yeats, O'Casey, and Synge shaped a nationalist consciousness based upon a mythology that was drawn only partially from actual historical documents, the image of Nation a. -

Issue 6 April 2017 a Literary Pamphlet €4

issue 6 april 2017 a literary pamphlet €4 —1— Denaturation Jean Bleakney from selected poems (templar poetry, 2016) INTO FLIGHTSPOETRY Taken on its own, the fickle doorbell has no particular score to settle (a reluctant clapper? an ill-at-ease dome?) were it not part of a whole syndrome: the stubborn gate; flaking paint; cotoneaster camouflaging the house-number. Which is not to say the occupant doesn’t have (to hand) lubricant, secateurs, paint-scraper, an up-to-date shade card known by heart. It’s all part of the same deferral that leaves hanging baskets vulnerable; although, according to a botanist, for most plants, short-term wilt is really a protective mechanism. But surely every biological system has its limits? There’s no going back for egg white once it’s hit the fat. Yet, some people seem determined to stretch, to redefine those limits. Why are they so inclined? —2— INTO FLIGHTSPOETRY Taken on its own, the fickle doorbell has no particular score to settle by Thomas McCarthy (a reluctant clapper? an ill-at-ease dome?) were it not part of a whole syndrome: the stubborn gate; flaking paint; cotoneaster Tara Bergin This is Yarrow camouflaging the house-number. carcanet press, 2013 Which is not to say the occupant doesn’t have (to hand) lubricant, secateurs, paint-scraper, an up-to-date Jane Clarke The River shade card known by heart. bloodaxe books, 2015 It’s all part of the same deferral that leaves hanging baskets vulnerable; Adam Crothers Several Deer although, according to a botanist, carcanet press, 2016 for most plants, short-term wilt is really a protective mechanism. -

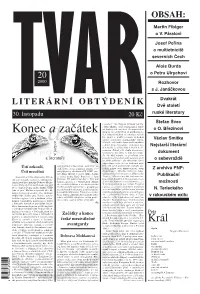

Konec a Začátek

OBSAH: Martin Fibiger o V. Páralovi Josef Peřina o multietnicitě severních Čech Alois Burda 20 o Petru Ulrychovi 2000 Rozhovor s J. Janáčkovou Dvakrát LITERÁRNÍ OBTÝDENÍK Dvě století 30. listopadu 20 Kč ruské literatury v podlost.“ Na Teigově příkladu pak Pe- Štefan Švec routka ukazuje osud avantgardních uměl- ců, kteří spojili svůj život s komunistickou o O. Březinovi Konec a začátek stranou, ale od třicátých let naráželi na to, že totalitární myšlení této instituce nebylo lze spojit s proklamovanou svobodou umělce a koncepcí avantgardního umění, Václav Smitka hlásícího se k tradici francouzské moderny a („Karel Teige byl jedním z těch mužů, kte- Nejstarší literární ří nevěděli, co dělají, když se hlásili ke ko- munismu. Pokud ještě vládla demokracie, ustavičně se mu zdálo, že není dost svobo- dokument v jazycev jazyce dy. Ale když nastalo, co přivolával, jeho a literatuře poslední kalný pohled viděl policisty, kteří o sebevraždě ho přišli zatknout“), ale zdůrazňuje i jeho odpovědnost za to, že toto totalitární myš- Ústí nekončí, rové nad ruskou literaturou „nové vlny“, je lení, vedoucí k potlačování svobody, po- však dobře, že na sympoziu zazněly rov- máhali zakrýt svou kultivovaností, svým Z archivu PNP: něž příspěvky absolventů PF UJEP: por- charizmatem: „Málokdo získal pro komu- Ústí nezačíná a literatuře trét Jiřího Muchy v pojetí Jiřího Jonáka nismus tolik přívrženců mezi vzdělanci jako Publikační S největší pravděpodobností se dá kon- a citlivá úvaha Hany Burešové o Janu Teige. (...) On více než kdo jiný svou oso- statovat, že kdyby nedošlo k odchodu lite- Hančovi. Tři pohostinné dny v Ústí nad bou pomáhal zastřít, že komunismus přiná- rární historičky a kritičky Dobravy Molda- Labem, spojené i s vlastivědnou exkurzí ší převahu hrubosti a nevzdělanosti (...).“ možnosti nové z Prahy do Ústí nad Labem, jen stěží do oseckého kláštera a do duchcovského V závěru nekrologu pak vzdává Teigemu by se tamější Pedagogická fakulta UJEP zámku, se staly argumentem o prospěšnos- i poctu: „(...) tento tvrdohlavý komunista (kde tč. -

Table of Contents (Pdf)

Contents Poetry Ireland Review 123 Eavan Boland 5 editorial Nan Cohen 7 a liking for clocks Eamon McGuinness 8 a gift Afric McGlinchey 9 in an instant of refraction and shadow Mara Bergman 10 the night we were dylan thomas Joseph Horgan 11 art history of emigration Maria Johnston 12 review: michael longley, john montague Harry Clifton 17 thérèse and the jug Simon West 18 on a trip to van diemen’s land Maresa Sheehan 20 our last day Niamh Boyce 21 hans ardently collects patients’ art work Alan Titley 22 maolra seoighe Proinsias Ó Drisceoil 23 review: biddy jenkinson, aifric mac aodha John D Kelly 27 the red glove Eva Bourke 28 small railway stations Catherine Phil MacCarthy 29 legacies of empire Richard W Halperin 30 the beach, malahide Matt Kirkham 31 kurt responds to adele’s call to remove a spider from the bathtub Susan Lindsay 32 when they’ve grown another me Jaki McCarrick 34 review: pete mullineaux, noel duffy, patrick moran Stav Poleg 39 listen, you have to read in a foreign language Noel Monahan 40 two women at a window Stephen Spratt 41 subjectivity AB Jackson 42 the mermayd Cathi Weldon 43 in the key of alzheimer’s John F Deane 44 old bones June Wentland 46 ‘their whiteness bears no relation to laundry ...’ Louis Mulcahy 47 potadóireacht na caolóige Harry Clifton 48 review: michael o’loughlin Matt Bryden 52 the lookout Orla Martin 53 the poets Catullus 54 ‘if you’re lucky you’ll dine well’ John Sewell 55 being alive Tess Adams 56 i hate my stinking therapist Patrick Holloway 57 barrage Eleanor Rees 58 st. -

2015 23Rd Annual Poets House Showcase Exhibition Catalog

2015 23rd Annual Poets House Showcase Exhibition Catalog |Poets House|10 River Terrace|New York, NY 10282|poetshouse.org| 5 The 2015 Poets House Showcase is made possible through the generosity of the hundreds of publishers and authors who have graciously donated their works. We are deeply grateful to Deborah Saltonstall Pease (1943 – 2014) for her foundational support. Many thanks are also due to the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York State Council on the Arts, the NYC Department of Cultural Affairs, the Leon Levy Foundation, and the many members of Poets House for their support of this project. 6 I believe that poetry is an action in which there enter as equal partners solitude and solidarity, emotion and action, the nearness to oneself, the nearness to mankind and to the secret manifestations of nature. – Pablo Neruda Towards the Splendid City Nobel Lecture, 1971 WELCOME to the 2015 Poets House Showcase! Each summer at Poets House, we celebrate all of the poetry published in the previous year in an all-inclusive exhibition and festival of readings from new work. In this year’s Showcase, we are very proud to present over 3,000 poetry books, chapbooks, broadsides, artist’s books, and multimedia projects, which represent the work of over 700 publishers, from commercial publishers to micropresses, both domestic and foreign. For twenty-three years, the annual Showcase has provided foundational support for our 60,000-volume library by helping us keep our collection current and relevant. With each Showcase, Poets House—one of the most extensive poetry collections in the nation—continues to build this comprehensive poetry record of our time. -

UCC Library and UCC Researchers Have Made This Item Openly Available

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Revisiting Irish poetic modernisms Author(s) Whittredge, Julia Katherine Publication date 2011-03 Original citation Whittredge, Julia Katherine, 2011. Revisting Irish Poetic Modernisms. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Link to publisher's http://library.ucc.ie/record=b2006564~S0 version Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2011, Julia Katherine Whittredge http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Embargo information Pages 25-346 have been restricted Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/324 from Downloaded on 2021-10-01T07:01:51Z Revisiting Irish Poetic Modernisms Dissertation submitted in candidacy for the degree of doctor of philosophy at the School of English, College of Arts, National University of Ireland, Cork, by Julia Katherine Whittredge, MA Under the Supervision of Professor Patricia Coughlan and Professor Alex Davis Head of Department: Professor James Knowles March 2011 Over years, and from farther and nearer, I had thought, I knew you— in spirit—I am of Ireland. Thomas MacGreevy, “Breton Oracles” 2 For John 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks to my parents for their encouragement, endless support, love, and for sharing their own love of books, art and music, for being friends as well as amazing parents. And for understanding my love for a tiny, rainy island 3,000 miles away. Thank you to my sister, Em, for her life-long friendship. Her loyalty and extraordinary creative and artistic talent are truly inspiring. -

Beckett and His Biographer: an Interview with James Knowlson José Francisco Fernández (Almería, Spain)

The European English Messenger, 15.2 (2006) Beckett and His Biographer: An Interview with James Knowlson José Francisco Fernández (Almería, Spain) James Knowlson is Emeritus Professor of French at the University of Reading. He is also the founder of the International Beckett Foundation (previously the Beckett Archive) at Reading, and he has written extensively on the great Irish author. He began his monumental biography, Damned to Fame:The Life of Samuel Beckett (London: Bloomsbury, 1996) when Beckett was still alive, and he relied on the Nobel Prize winner’s active cooperation in the last months of his life. His book is widely acknowledged as the most accurate source of information on Beckett’s life, and can only be compared to Richard Ellmann’s magnificent biography of James Joyce. James Knowlson was interviewed in Tallahassee (Florida) on 11 February 2006, during the International Symposium “Beckett at 100: New Perspectives” held in that city under the sponsorship of Florida State University. I should like to express my gratitude to Professor Knowlson for giving me some of his time when he was most in demand to give interviews in the year of Beckett’s centennial celebrations. José Francisco Fernández JFF: Yours was the only biography on or even a reply to the earlier biography of authorised by Beckett. That must have been Deirdre Bair. It needs to stand on its own two a great responsibility. Did it represent at any feet. And I read with great fascination the time a burden? Knowing that what you wrote biography of Deirdre Bair and have never said would be taken as ‘the truth’. -

Modern Irish Poetry, 1800–2000 Over the Last Two Centuries, Ireland Has Produced Some of the World’S Most Outstanding and Best-Loved Poets, from Thomas Moore to W

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-84673-8 - The Cambridge Introduction to Modern Irish Poetry, 1800-2000 Justin Quinn Frontmatter More information The Cambridge Introduction to Modern Irish Poetry, 1800–2000 Over the last two centuries, Ireland has produced some of the world’s most outstanding and best-loved poets, from Thomas Moore to W. B. Yeats to Seamus Heaney. This introduction not only provides an essential overview of the history and development of poetry in Ireland, but also offers new approaches to aspects of the field. Justin Quinn argues that the language issues of Irish poetry have been misconceived and re-examines the divide between Gaelic and Anglophone poetry. Quinn suggests an alternative to both nationalist and revisionist interpretations and fundamentally challenges existing ideas of Irish poetry. This lucid book offers a rich contextual background against which to read the individual works, and pays close attention to the major poems and poets. Readers and students of Irish poetry will learn much from Quinn’s sharp and critically acute account. Justin Quinn is Associate Professor of English and American Studies at the Charles University, Prague. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-84673-8 - The Cambridge Introduction to Modern Irish Poetry, 1800-2000 Justin Quinn Frontmatter More information Cambridge Introductions to Literature This series is designed to introduce students to key topics and authors. Accessible and lively, these introductions will also appeal to readers who want to broaden their understanding of the books and authors they enjoy. r Ideal for students, teachers, and lecturers r Concise, yet packed with essential information r Key suggestions for further reading Titles in this series: Christopher Balme The Cambridge Introduction to Theatre Studies Eric Bulson The Cambridge Introduction to James Joyce Warren Chernaik The Cambridge Introduction to Shakespeare’s History Plays John Xiros Cooper The Cambridge Introduction to T. -

Irish Anthologies and Literary History

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) A commodious vicus of recirculation: Irish anthologies and literary history Leerssen, J. Publication date 2010 Document Version Submitted manuscript Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Leerssen, J. (2010). A commodious vicus of recirculation: Irish anthologies and literary history. (Working papers European Studies Amsterdam; No. 10). Opleiding Europese Studies, Universiteit van Amsterdam. http://www.uva.nl/disciplines/europese- studies/onderzoek/working-papers.html General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 WORKING PAPERS EUROPEAN STUDIES AMSTERDAM 10 Joep Leerssen A Commodious Vicus of Recirculation: Irish Anthologies and Literary History Opleiding Europese Studies, Universiteit van Amsterdam 2010 Joep Leerssen is professor of Modern European Literature at the University of Amsterdam and Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences Professor. -

Call No. Responsibility Item Publication Details Date Note 1

Call no. Responsibility Item Publication details Date Note TKNC0001 Roberts, H. Song, to a gay measure Dublin: printed at the Dolmen 1951 "200 copies." Neville Press TKNC0002 Promotional notice for Travelling tinkers, a book of Dolmen Press ballads by Sigerson Clifford TKNC0003 Promotional notice for Freebooters by Mauruce Kennedy Dolmen Press TKNC0004 Advertisement for Dolmen Press Greeting cards &c Dolmen Press TKNC0005 The reporter: the magazine of facts and ideas. Volume July 16, 1964 contains 'In the 31 no. 2 beginning' (verse) by Thomas Kinsella TKNC0006 Clifford, Travelling tinkers Dublin: Dolmen Press 1951 Of one hundred special Sigerson copies signed by the author this is number 85. Insert note from Thomas Kinsella. TKNC0007 Kinsella, Thomas The starlit eye / Thomas Kinsella ; drawings by Liam Dublin: Dolmen Press 1952 Set and printed by hand Miller at the Dolmen Press, Dublin, in an edition of 175 copies. March 1952. (p. [8]). TKNC0008 Kinsella, Thomas Galley proof of Poems [Glenageary, County Dublin]: 1956 Galley proof Dolmen Press TKNC0009 Kinsella, Thomas The starlit eye / Thomas Kinsella ; drawings by Liam Dublin : Dolmen Press 1952 Of twenty five special Miller copies signed by the author this is number 20. Set and printed by hand at the Dolmen Press, Dublin, in an edition of 175 copies. March 1952. TKNC0010 Promotional postcard for Love Duet from the play God's Dolmen Press gentry by Donagh MacDonagh TKNC0011 Irish writing. No. 24 Special issue - Young writers issue Dublin Sep-53 1 Thomas Kinsella Collection Listing Call no. Responsibility Item Publication details Date Note TKNC0012 Promotional notice for Dolmen Chapbook 3, The perfect Dolmen Press 1955 wife a fable by Robert Gibbings with wood engravings by the author TKNC0013 Pat and Mick Broadside no.