The University of Chicago Rendering Empire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MOULDINGS | STAIR PARTS | BOARDS | EXTERIOR MILLWORK MIDWEST CHICAGO DISTRIBUTION CENTER Our Our STORY FAMILY DEEP ROOTS

MOULDINGS | STAIR PARTS | BOARDS | EXTERIOR MILLWORK MIDWEST CHICAGO DISTRIBUTION CENTER our our STORY FAMILY DEEP ROOTS. HIGH STANDARDS. BRIGHT FUTURE. EMPIRE IS NOW A PART OF THE NOVO FAMILY. Founded in 1946 Empire has grown into With a geographic footprint that touches Novo Building Products is the industry door shops, retail home centers, and one of the largest millwork distribution the majority of the eastern half of the leading manufacturer and distributor of millwork manufacturing partners and manufacturing companies in the United States, Empire is positioned for mouldings, stair parts, doors, and specialty throughout the United States and parts United States. continued expansion. building products. We are proud to serve of Canada and Mexico. LJ Smith building material dealers (lumberyards), Puyallup, WA L.J. Smith Learn more at . Salem, NH novobp.com Empire Zeeland, MI L.J. Smith Empire A llentown, PA Empire Bowerston, OH Channahon, IL L.J. Smith West Valley City, UT Empire REFRESH. Ornamental Mouldings Empire Archdale, NC Dallas, TX L.J. Smith Ball Ground, GA L.J. Smith Corona, CA Southwest Dallas, TX REVIVE. L.J. Smith Empire Houston, TX Lakeland, FL RENEW. 2 empireco.com | 800.253.9000 empireco.com | 800.253.9000 3 Style is individual, personal, and unique. Make your room a reflection of you... DISCOVER YOUR STYLE HERE Achieve a similar look using: P 450 Chair Rail | 041 Crown | 5030 Architrave | 312 Casing | L 163E Base Colonial, Ranch, Traditional, Midwestern, Early American, Inviting and Timeless... The new and improved Empireco.com. Explore our comprehensive collections of mouldings, Classic Classic Mouldings enhance any home style from Midwestern to stair parts, boards, and exterior millwork as well Early American, and blend perfectly with the classic style furnishing as find inspiration for every room in the home. -

£¤A1a £¤Us1 £¤192 £¤Us1 £¤A1a

S T r G A K A W R o A C T A P I Y TRAS R O ON A L M I N R N M R O S T EM P G T E D D p E Y Y I F A O S S N NV O S L D A GI L DU ERN L R M N N A H CASTL ES K S E S N T P A T M E T U RAFFORD C A R I A N T L I I N E K H M O L L D R R C C i D A I R O P S Y T U W S N P LIMPKIN EL N B P E A G D TA I S T C A L O c U N I A O T R B L S O A U R A N O SP T B T K SPUR E E I O E P L L S N R H E R S M I C Y OUNT S D RY N H WALK T I A O S R W L U a A E D P A1A E E M O N U R O M L O A A RD F A D A H H Y S H W U P R TR S EN E N I DAV T l ADDISO N R A K E A S D P V E O R E A R O A O A R Y £ S E T K Y R ¤ B E T R O Y N O L A T M D Y N ADDIS L Y C I U ON N N S V E T K K AT A A R OLA A O I C A R L R O V Z N P A NA EE K R I B L TR R V L L AY N C B A E M L S E E r M O A L L E R L M O I A R O C U A P G A T G R R SS l E M Q BLA C R R M JORDAN H A E E N M E S R S U I S R U E P E T H N C N A A DE R U I IR AR G RECRE T G AT S W M D H M WILLOW C M ION R L REE B E PA P A K A E A D E E A C B L I US1 C L T S G R R U Y K E R S R P IB L I ERA D W N D Q A C O E N RS I A PINEDA O L N R E N y O T N F THIRD A R M HOF A S T G £ w T I L D ¤ N E S s E M S D H A BO B L S O Q H W R T U H E K PIO N K O CAP H C S E R R U O T I G L O C DO V A A F R G O H E M O TRU O a CEN L R O O L E G N L R L E N S H R d I I R B W E A Y N R O W I R e A V C U W E F FIRST R A M K W T K H n L G T A I JEN S E LLO i R ANE E R R C O A A E T A A E I P I E H FIRST S H Y P L N D SKYLARK R T A H A N O S S City of Melbourne K T S L I F E O K CASABELLA 1 E RAMP U A T OCEAN N S R S R I P E SANDPIPER E R A O -

The Novels of Edouard Rod (1857-1910)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska) University Studies of the University of Nebraska 1938 The Novels of Edouard Rod (1857-1910) James Raymond Wadsworth University of Nebraska Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/univstudiespapers Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, and the French and Francophone Language and Literature Commons Wadsworth, James Raymond, "The Novels of Edouard Rod (1857-1910)" (1938). Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska). 117. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/univstudiespapers/117 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Studies of the University of Nebraska at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers from the University Studies series (The University of Nebraska) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VoL. XXXVIII-Nos. 3-4 1938 UNIVERSITY STUDIES PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA COMMITTEE ON PUBLICATIONS M.A. BASOCO J. E. KIRSHMAN G. W. ROSENLOF HARRY KURZ FRED W. UPSON H. H. MARVIN D. D. WHITNEY LOUISE POUND R. A. MILLER THE NOVELS OF EDOUARD ROD (1857-1910) BY JAMES RAYMOND WADSWORTH ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ROMANCE LANGUAGES UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA LINCOLN, NEBRASKA 1938 THE UNIVERSITY STUDIES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA VOLUME XXXVIII LINCOLN PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY 1938 CONTENTS 1-2-FRYE, PROSSER HALL. Plato .............. 1-113 3--4-WAoswoRTH, JAMES RAYMOND. The Novels of Edouard Rod (1857-1910) ............. 115-173 ii UNIVERSITY STUDIES VoL. XXXVIII-Nos. 3--4 1938 THE NOVELS OF EDOUARD ROD (1857-1910) BY JAMES RAYMOND WADSWORTH ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ROMANCE LANGUAGES UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page PREFACE \' I. -

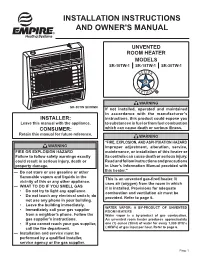

Installation INSTRUCTIONS and OWNER's MANUAL

Installation INSTRUCTIONS AND OWNER'S MANUAL UNVENTED ROOM HEATER MODELS SR-10TW-1 SR-18TW-1 SR-30TW-1 WARNING SR-30TW SHOWN If not installed, operated and maintained in accordance with the manufacturer’s INSTALLER: instructions, this product could expose you Leave this manual with the appliance. to substances in fuel or from fuel combustion CONSUMER: which can cause death or serious illness. Retain this manual for future reference. WARNING “FIRE, EXPLOSION, AND ASPHYXIATION HAZARD WARNING Improper adjustment, alteration, service, FIRE OR EXPLOSION HAZARD maintenance, or installation of this heater or Failure to follow safety warnings exactly its controls can cause death or serious injury. could result in serious injury, death or Read and follow instructions and precautions property damage. in User’s Information Manual provided with — Do not store or use gasoline or other this heater.” flammable vapors and liquids in the This is an unvented gas-fired heater. It vicinity of this or any other appliance. uses air (oxygen) from the room in which — WHAT TO DO IF YOU SMELL GAS it is installed. Provisions for adequate • Do not try to light any appliance. combustion and ventilation air must be • Do not touch any electrical switch; do provided. Refer to page 6. not use any phone in your building. • Leave the building immediately. WATER VAPOR: A BY-PRODUCT OF UNVENTED • Immediately call your gas supplier ROOM HEATERS from a neighbor’s phone. Follow the Water vapor is a by-product of gas combustion. gas supplier’s instructions. An unvented room heater produces approximately • If you cannot reach your gas supplier, one (1) ounce (30ml) of water for every 1,000 BTU’s call the fire department. -

The Bilge November 2020

The Bilge November 2020 Ridgeway Avenue Soldiers Point 2315 Commodore’s Report Commodore’s Report COMMODORE REPLY AT AGM 1. Welcome to members of PSYC thank you for your attendance. 2. Welcome the returning directors thank you for your past service. a. Rick Pacey – Vice Commodore b. David Simm – Rear Commodore c. Anne Evans – Treasurer d. Marina Budisavljevic – Secretary e. Lotte Baker – Assistant Secretary & Licensee in Charge f. Steve Plante – Director 3. Welcome the new directors a. Ross Macdonald – Club Captain b. Peter Oliver – Director 4. Appointment of the Auditors a. Confirmed as W Morley & Co Pty Ltd (Nelson Bay) 5. General Business a. Special thankyou to Board Members stepping down: i. Commodore - John Townsend ii. Club Captain – John Glease. b. Special thank you to the “Volunteers” at PSYC you know who you are and the work you do is appreciated to keep our club and sailing activities in Port Stephens going week in week out. c. Challengers facing the PSYC i. Covid – 19 impact on the club’s activities, income and members & visitors Health and Safety. Thank you to John Townsend for his dedication and attention to detail making the PSYC, members & visitors safe during 2020. ii. Profitability and Provision of Services to members. 1. PSYC a “not for profit” still has bills to pay and services to be offered to its members. 2. Your board will be conducting a “Budget Review” in the first few months which will involve all aspects Financial. a. Membership Fees. b. Mooring Fees and Charges. c. Bar Income & Expenses. d. Sub-Leasing of club space for other board approved activities, social events, etc iii. -

Rigging Guide

R I G G I N G G U I D E Sail it. Live it. Love it. INTRODUCTION Congratulations on the purchase of your new RS400 and thank you for choosing an RS. We are confident that you will have many hours of great sailing and racing in this truly excellent design. Important Note The RS400 is an exciting boat to sail and offers fantastic performance. It is a light weight racing dinghy and should be treated with care. In order to get the most enjoyment from your boat and maintain it in top condition, please read this manual carefully. Whilst your RS boat has been carefully prepared, it is important that new owners should check that shackles, knots and mast step bolts etc. are tight. This is especially important when the boat is new, as travelling can loosen seemingly tight fittings and knots. It is also important to regularly check such items prior to sailing. Make sure that you have a basic tool kit with you the first time you rig the boat in case there are tuning / settings changes that you wish to make. Contents RIGGING INSTRUCTIONS TUNING AND SAILING TIPS CARE AND MAINTENANCE CLASS ASSOCIATION INSURANCE For further information, spares and accessories, please contact: LDC Racing Sailboats, Premier Way, Abbey Park, Romsey, SO51 9DQ Tel. +44 (0)17 9452 6760 Fax. +44 (0)17 9427 8418 Email. [email protected] RIGGING INSTRUCTIONS 1). The top straps are adjustable for length and reach. Spend time setting the straps to suit your size and preferred hiking position. -

De/Colonizing Preservice Teacher Education: Theatre of the Academic Absurd

Volume 10 Number 1 Spring 2014 Editor Stephanie Anne Shelton http://jolle.coe.uga.edu De/colonizing Preservice Teacher Education: Theatre of the Academic Absurd Dénommé-Welch, Spy, [email protected] University of Regina, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada Montero, M. Kristiina, [email protected] Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada Abstract Where does the work of de/colonizing preservice teacher education begin? Aboriginal children‘s literature? Storytelling and theatrical performance? Or, with a paradigm shift? This article takes up some of these questions and challenges, old and new, and begins to problematize these deeper layers. In this article, the authors explore the conversations and counterpoints that came about looking at the theme of social justice through the lens of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit (FNMI) children‘s literature. As the scope of this lens widened, it became more evident to the authors that there are several filters that can be applied to the work of de/colonizing preservice teacher education programs and the larger educational system. This article also explores what it means to act and perform notions of de/colonization, and is constructed like a script, thus bridging the voices of academia, theatre, and Indigenous knowledge. In the first half (the academic script) the authors work through the messy and tangled web of de/colonization, while the second half (the actors‘ script) examines these frameworks and narratives through the actor‘s voice. The article calls into question the notions of performing inquiry and deconstructing narrative. Key words: decolonizing education; Indigenizing the academy; preservice teacher education; performing decolonization; decolonizing narrative; Indigenous knowledge; First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples of Canada; North America. -

Shakespeare Unlimited: How King Lear Inspired Empire

Shakespeare Unlimited: How King Lear Inspired Empire Ilene Chaiken, Executive Producer Interviewed by Barbara Bogaev A Folger Shakespeare Library Podcast March 22, 2017 ---------------------------- MICHAEL WITMORE: Shakespeare can turn up almost anywhere. [A series of clips from Empire.] —How long you been plannin’ to kick my dad off the phone? —Since the day he banished me. I could die a thousand times… just please… From here on out, this is about to be the biggest, baddest company in hip-hop culture. Ladies and gentlemen, make some noise for the new era of Hakeem Lyon, y’all… MICHAEL: From the Folger Shakespeare Library, this is Shakespeare Unlimited. I‟m Michael Witmore, the Folger‟s director. This podcast is called “The World in Empire.” That clip you heard a second ago was from the Fox TV series Empire. The story of an aging ruler— in this case, the head of a hip-hop music dynasty—who sets his three children against each other. Sound familiar? As you will hear, from its very beginning, Empire has fashioned itself on the plot of King Lear. And that‟s not the only Shakespeare connection to the program. To explain all this, we brought in Empire’s showrunner, the woman who makes everything happen on time and on budget, Ilene Chaiken. She was interviewed by Barbara Bogaev. ---------------------------- BARBARA BOGAEV: Well, Empire seems as if its elevator pitch was a hip-hop King Lear. Was that the idea from the start? ILENE CHAIKEN: Yes, as I understand it, now I didn‟t create Empire— BOGAEV: Right, because you‟re the showrunner, and first there‟s a pilot, and then the series gets picked up, and then they pick the showrunner. -

Boardwalk Empire’ Comes to Harlem

ENTERTAINMENT ‘Boardwalk Empire’ Comes to Harlem By Ericka Blount Danois on September 9, 2013 “One looks down in secret and sees many things,” Dr. Valentin Narcisse (Jeffrey Wright) deadpans, speaking to Chalky White (Michael K. Williams). “You know what I saw? A servant trying to be a king.” And so begins a dance of power, politics and personality between two of the most electrifying, enigmatic actors on the television screen today. Each time the two are on screen—together or apart—they breathed new life into tonight’s premiere episode of Boardwalk Empire season four, with dark humor, slight smiles, powerful glances, smart clothes and killer lines. Entitled “New York Sour,” the episode opened with bombast, unlike the slow boil of previous seasons. Set in 1924, we’re introduced to the tasteful opulence of Chalky White’s new club, The Onyx, decorated with sconces custom-made in Paris and shimmering, shapely dancing girls. Chalky earned an ally, and eventually a partnership to be able to open the club, with former political boss and gangster Nucky Thompson (Steve Buscemi) by saving Nucky’s life last season. This sister club to the legendary Cotton Club in Harlem is Whites-only, but features Black acts. There are some cringe-worthy moments when Chalky, normally proud and infallible, has to deal with racism and bends over to appease his White clientele. But more often, Chalky—a Texas- born force to be reckoned with—breathes an insistent dose of much needed humor into what sometimes devolves into cheap shoot ’em up thrills this season. The meeting of the minds between Narcisse and Chalky takes root in the aftermath of a mistake by Chalky’s right hand man, Dunn Purnsley (Erik LaRay Harvey), who engages in an illicit interracial tryst that turns out to be a dramatic, racially-charged sex game gone horribly wrong. -

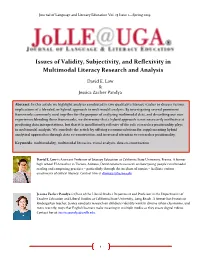

Issues of Validity, Subjectivity, and Reflexivity in Multimodal Literacy Research and Analysis

Journal of Language and Literacy Education Vol. 15 Issue 1—Spring 2019 Issues of Validity, Subjectivity, and Reflexivity in Multimodal Literacy Research and Analysis David E. Low & Jessica Zacher Pandya Abstract: In this article we highlight analyses conducted in two qualitative literacy studies to discuss various implications of a blended, or hybrid, approach to multimodal analysis. By investigating several prominent frameworks commonly used together for the purpose of analyzing multimodal data, and describing our own experiences blending these frameworks, we determine& that a hybrid approach is not necessarily ineffective at producing data interpretations, but that it is insufficiently reflexive of the role researcher positionality plays in multimodal analysis. We conclude the article by offering recommendations for supplementing hybrid analytical approaches through data co-construction and increased attention to researcher positionality. Keywords: multimodality, multimodal literacies, visual analysis, data co-construction David E. Low is Assistant Professor of Literacy Education at California State University, Fresno. A former high school ELA teacher in Tucson, Arizona, David conducts research on how young people’s multimodal reading and composing practices – particularly through the medium of comics – facilitate various enactments of critical literacy. Contact him at [email protected]. Jessica Zacher Pandya is Chair of the Liberal Studies Department and Professor in the Departments of Teacher Education and Liberal Studies at California State University, Long Beach. A former San Francisco kindergarten teacher, Jessica conducts research on children's identity work in diverse urban classrooms, and more recently, ways that English learners make meaning in multiple modes as they create digital videos. Contact her at: [email protected]. -

Page 1 of 279 FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS

FLORIDA LRC DECISIONS. January 01, 2012 to Date 2019/06/19 TITLE / EDITION OR ISSUE / AUTHOR OR EDITOR ACTION RULE MEETING (Titles beginning with "A", "An", or "The" will be listed according to the (Rejected / AUTH. DATE second/next word in title.) Approved) (Rejectio (YYYY/MM/DD) ns) 10 DAI THOU TUONG TRUNG QUAC. BY DONG VAN. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 DAI VAN HAO TRUNG QUOC. PUBLISHER NHA XUAT BAN VAN HOC. REJECTED 3D 2017/07/06 10 POWER REPORTS. SUPPLEMENT TO MEN'S HEALTH REJECTED 3IJ 2013/03/28 10 WORST PSYCHOPATHS: THE MOST DEPRAVED KILLERS IN HISTORY. BY VICTOR REJECTED 3M 2017/06/01 MCQUEEN. 100 + YEARS OF CASE LAW PROVIDING RIGHTS TO TRAVEL ON ROADS WITHOUT A APPROVED 2018/08/09 LICENSE. 100 AMAZING FACTS ABOUT THE NEGRO. BY J. A. ROGERS. APPROVED 2015/10/14 100 BEST SOLITAIRE GAMES. BY SLOANE LEE, ETAL REJECTED 3M 2013/07/17 100 CARD GAMES FOR ALL THE FAMILY. BY JEREMY HARWOOD. REJECTED 3M 2016/06/22 100 COOL MUSHROOMS. BY MICHAEL KUO & ANDY METHVEN. REJECTED 3C 2019/02/06 100 DEADLY SKILLS SURVIVAL EDITION. BY CLINT EVERSON, NAVEL SEAL, RET. REJECTED 3M 2018/09/12 100 HOT AND SEXY STORIES. BY ANTONIA ALLUPATO. © 2012. APPROVED 2014/12/17 100 HOT SEX POSITIONS. BY TRACEY COX. REJECTED 3I 3J 2014/12/17 100 MOST INFAMOUS CRIMINALS. BY JO DURDEN SMITH. APPROVED 2019/01/09 100 NO- EQUIPMENT WORKOUTS. BY NEILA REY. REJECTED 3M 2018/03/21 100 WAYS TO WIN A TEN-SPOT. BY PAUL ZENON REJECTED 3E, 3M 2015/09/09 1000 BIKER TATTOOS. -

Dossier De Presse TOUT SAVOIR SUR EMPIRE

DOSSIER DE PRESSE TOUT SAVOIR SUR EMPIRE DÉCOUVRIR LES PREMIÈRES IMAGES DE LA SAISON 1 SUCCESS STORY : Série dramatique n°1 de la saison 2014/15 aux USA Série n°2 de la saison 2014/15 aux USA, derrière Big Bang Theory sur CBS Meilleur score pour une nouvelle série aux USA depuis Desperate Housewives et Grey’s Anatomy en 2004-2005 Plus forte progression durant une première saison (+65%) depuis Docteur House en 2004 Série la plus tweetée avec 627 369 live tweets par épisode (devant The Walking Dead) SYNOPSIS Lucious Lyon (Terrence Howard, nominé aux lorsque son ex-femme, Cookie (Taraji P. Henson, Oscars et aux Golden Globes pour Hustle & nominée aux Oscars et aux Emmy Awards, Flow) est le roi du hip-hop. Ancien petit voyou, L’étrange histoire de Benjamin Button, Person son talent lui a permis de devenir un artiste of Interest), revient sept ans plus tôt que prévu, talentueux mais surtout le président d’Empire après presque 20 ans de détention. Audacieuse Entertainment. Pendant des années, son et sans scrupule, Cookie considère qu’elle s’est règne a été sans partage. Mais tout bascule sacrifiée pour que Lucious puisse démarrer sa lorsqu’il apprend qu’il est atteint d’une maladie carrière puis bâtir un empire, en vendant de la dégénérative. Il est désormais contraint de drogue. Trafic pour lequel elle a été envoyée transmettre à ses trois fils les clefs de son en prison. empire, sans faire éclater la cellule familiale déjà fragile. Pour le moment, Lucious reste à la tête d’Empire Entertainment.