Issues of Validity, Subjectivity, and Reflexivity in Multimodal Literacy Research and Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New GP Design Unveiled at the Worlds in Sri Lanka Editor’S Letter Contents

S pr in g www.gp14.org GP14 Class International Association 20 11 New GP design unveiled at the worlds in Sri Lanka Editor’s letter Contents One of the most important themes of this issue is training. The Features importance of getting newcomers into the sport cannot be over- emphasised in these days when there is so much competition for 4 President’s piece Return to Abersoch everyone’s time and money. With any luck the recession will make Ian Dobson on expectation people think twice about flying off abroad and more interested in a 6 Welcome to Gill Beddow 13 versus reality at the Nationals local low-cost hobby which will teach them and their children a 8 From the forum new skill while providing an instant social life. View from astern Phil Green on the Nationals Phil Hodgkins, a young sailor from ??, has recently been elected to Racing 16 from the other end of the fleet the Association Committee with responsibility for training and you 11 Championship round-up can read about his plans for training days organised for those clubs Book review who would like them. The RYA is also very interested in training and Hugh Brazier tells how Goldilocks Overseas reports 32 has recently expanded their remit to getting adults onto the water, learned the racing rules rather than concentrating on youngsters with their OnBoard 18 News from Ireland scheme. You can read about their latest initiative, Activate your 21 The Australian trapeze Fleet, and how it can help you. I have seen first-hand how a good training scheme, pulling in Area reports newcomers, helping them to build their skills and – most 24 North West Region importantly – to become involved in the work of helping others in the club, can build up a club from only having a few half-hearted 26 North East Area GP sailors in ageing boats to a large, young and competitive fleet in 27 Scottish Area the space of a few years. -

£¤A1a £¤Us1 £¤192 £¤Us1 £¤A1a

S T r G A K A W R o A C T A P I Y TRAS R O ON A L M I N R N M R O S T EM P G T E D D p E Y Y I F A O S S N NV O S L D A GI L DU ERN L R M N N A H CASTL ES K S E S N T P A T M E T U RAFFORD C A R I A N T L I I N E K H M O L L D R R C C i D A I R O P S Y T U W S N P LIMPKIN EL N B P E A G D TA I S T C A L O c U N I A O T R B L S O A U R A N O SP T B T K SPUR E E I O E P L L S N R H E R S M I C Y OUNT S D RY N H WALK T I A O S R W L U a A E D P A1A E E M O N U R O M L O A A RD F A D A H H Y S H W U P R TR S EN E N I DAV T l ADDISO N R A K E A S D P V E O R E A R O A O A R Y £ S E T K Y R ¤ B E T R O Y N O L A T M D Y N ADDIS L Y C I U ON N N S V E T K K AT A A R OLA A O I C A R L R O V Z N P A NA EE K R I B L TR R V L L AY N C B A E M L S E E r M O A L L E R L M O I A R O C U A P G A T G R R SS l E M Q BLA C R R M JORDAN H A E E N M E S R S U I S R U E P E T H N C N A A DE R U I IR AR G RECRE T G AT S W M D H M WILLOW C M ION R L REE B E PA P A K A E A D E E A C B L I US1 C L T S G R R U Y K E R S R P IB L I ERA D W N D Q A C O E N RS I A PINEDA O L N R E N y O T N F THIRD A R M HOF A S T G £ w T I L D ¤ N E S s E M S D H A BO B L S O Q H W R T U H E K PIO N K O CAP H C S E R R U O T I G L O C DO V A A F R G O H E M O TRU O a CEN L R O O L E G N L R L E N S H R d I I R B W E A Y N R O W I R e A V C U W E F FIRST R A M K W T K H n L G T A I JEN S E LLO i R ANE E R R C O A A E T A A E I P I E H FIRST S H Y P L N D SKYLARK R T A H A N O S S City of Melbourne K T S L I F E O K CASABELLA 1 E RAMP U A T OCEAN N S R S R I P E SANDPIPER E R A O -

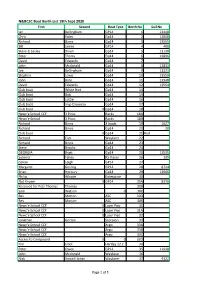

N&BCSC Boat Berth List 19Th Sept 2020

N&BCSC Boat Berth List 19th Sept 2020 First Second Boat Type Berth No Sail No Ian Bellingham GP14 1 13440 Chris Yates Gp14 2 13868 Richard Binns Gp14 3 13555 Bill James GP14 4 408 Steve & Lesley Dixon Gp14 5 13138 Peter Thoms Gp14 6 13896 David Edwards Gp14 7 John Mcdonald Gp14 8 12831 Joe Bellingham Gp14 9 13321 Stephen Lewis Gp14 10 13559 John Bate Gp14 11 13948 David Edwards Gp14 12 13554 Club boat White Riot Gp14 14 Club boat Bob Gp14 15 Club boat Lottie Gp14 16 Club boat Insp Clouseau Gp14 17 Club boat 0 Gp14 18 Newc'e School CCF 3 Picos Racks 18A Newc'e School 3 Picos Racks 18B Richard Binns 3 boats 19 1627 Richard Binns Gp14 20 20 Club boat 0 Gp14 21 Red Richard Fish Wayfarer 22 Richard Binns Gp14 23 Steve Brooks Gp14 24 GEORGIA Bratt Gp14 25 12535 Suteera Fahey RS Vision 26 195 Ceiran Leigh GP14 27 Margaret Gosling GP14 28 8724 Brian Horbury Gp14 29 13066 Philip Whaite Enterprise 30 Not Known 0 GP14 30A 8376 Reserved for Pete Thomas Thomas 30B Sam Watson 0 30C Bev Morton ASC 30D Bev Morton ASC 30E Newc'e School CCF 0 Laser Pico 31 Newc'e School CCF 0 Laser Pico 31A Newc'e School CCF 0 Laser Pico 32 Jonathan Gorton Scorpion 33 Newc'e School CCF Argo 33A Newc'e School CCF Argo 33B Newc'e School CCF Argo 33C Access to Compound 0 0 33D Tim Elliot Hartley 12.2 34 Peter Owen GP14 35 11940 John Mcdonald Wayfarer 36 Nick Howell-Jones Wayfarer 37 9322 Page 1 of 5 Sean Barton Gp14 38 Martin Kirby Gp14 39 18673 Sam Barker Gp14 40 10459 Mark Price GP14 41 Gill Fox Gp14 42 6244 Andrew Dulla Gp14 43 Tracy Haden Gp14 44 11643 Rob Barlow GP14 -

De/Colonizing Preservice Teacher Education: Theatre of the Academic Absurd

Volume 10 Number 1 Spring 2014 Editor Stephanie Anne Shelton http://jolle.coe.uga.edu De/colonizing Preservice Teacher Education: Theatre of the Academic Absurd Dénommé-Welch, Spy, [email protected] University of Regina, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada Montero, M. Kristiina, [email protected] Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada Abstract Where does the work of de/colonizing preservice teacher education begin? Aboriginal children‘s literature? Storytelling and theatrical performance? Or, with a paradigm shift? This article takes up some of these questions and challenges, old and new, and begins to problematize these deeper layers. In this article, the authors explore the conversations and counterpoints that came about looking at the theme of social justice through the lens of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit (FNMI) children‘s literature. As the scope of this lens widened, it became more evident to the authors that there are several filters that can be applied to the work of de/colonizing preservice teacher education programs and the larger educational system. This article also explores what it means to act and perform notions of de/colonization, and is constructed like a script, thus bridging the voices of academia, theatre, and Indigenous knowledge. In the first half (the academic script) the authors work through the messy and tangled web of de/colonization, while the second half (the actors‘ script) examines these frameworks and narratives through the actor‘s voice. The article calls into question the notions of performing inquiry and deconstructing narrative. Key words: decolonizing education; Indigenizing the academy; preservice teacher education; performing decolonization; decolonizing narrative; Indigenous knowledge; First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples of Canada; North America. -

Roll of Champions

CVLSC Roll of Champions Nov-16 Event Year Champion Feb Class Race Day - Laser 2016 Phil Pattullo Frostbite AM - Laser 2016 Phil Pattullo May Class Race Day - Laser 2016 Phil Pattullo Spring Points - Laser 2016 Phil Pattullo Autumn Points AM - Laser 2016 Phil Pattullo Mercury Trophy 35 - 44 yrs 2016 Phil Pattullo - Laser Frostbite AM - Flying Fifteen 2016 Bill Chard & Ken Comrie Frostbite PM - Flying Fifteen 2016 Bill Chard & Ken Comrie Early Summer Points AM - Flying Fifteen 2016 Bill Chard & Ken Comrie August Class Race Day - Flying Fifteen 2016 Bill Chard & Ken Comrie Autumn Points AM - Flying Fifteen 2016 Bill Chard & Ken Comrie Frostbite AM - A Handicap 2016 Steve Jones & Andy Harris - RS400 May Class Race Day - A Handicap 2016 Steve Jones & Andy Harris - RS400 Summer Regatta - A Handicap 2016 Steve Jones & Andy Harris - RS400 Admirals Chase 2016 Steve Jones & Andy Harris - RS400 Winter Points - A Handicap 2015 Steve Jones & Andy Harris - RS400 Early Summer Points AM - Solo 2016 Alex Timms Early Summer Points PM - Solo 2016 Alex Timms Summer Points - Solo 2016 Alex Timms August Class Race Day - Solo 2016 Alex Timms Feb Class Race Day - A Handicap 2016 Chris Goldhawk - RS100 Early Summer Points PM - A Handicap 2016 Chris Goldhawk - RS100 Marshall Trophy 2016 Chris Goldhawk - RS100 Summer Points - A Handicap 2016 Chris Goldhawk - RS100 Spring Points - A Handicap 2016 Andy Jones - RS100 Early Summer Points AM - A Handicap 2016 Andy Jones - RS100 Macklin Trophy 45 - 54 yrs 2016 Andy Jones - RS100 Feb Class Race Day - Flying Fifteen 2016 -

Blast Reaching at the NSW States Photos Neil Waterman ©

Blast Reaching at the NSW States Photos Neil Waterman © Volume 153 June 2006 NS14 Bulletin President’s Message First of all I would like to introduce myself to those who don’t know me as by virtue of being elected NSW President I am also the National President under the current constitution. This will change under the proposed revisions to the constitution whereby the President will be elected. I have been in NSs for 20 years mainly based at Northbridge although I have moved in and out of the Association as Hugh and Penny’s boat interests have changed (eg FAs, Lasers, MGs, 29ers, 16’ skiffs, and yachts). This has allowed me to have some exposure as to how other classes are run. For the last couple of seasons we have had three NSs in the family and I am keen to see the class get back to the strength it had a number of years ago. In this context I would like to outline a number of actions I think we need to take to help rejuvenate the class and bring the numbers participating at a class level back to where we used to be. There is no doubt there is a lot more competition for people’s time nowadays, but I feel that we have an opportunity to position this class as a great way for people to use the time they have. The key challenges are to get people sailing in regattas and to get people building new boats again. First, I think we need to market the NS14 using the strengths of the class to demonstrate that this class will suit a broad spectrum of sailors. -

South Shore Host to Penguin Regional Championship Races

Page 2 SSYC Compass October, 1951 there were quite a few protests. negligable and so that no place is South Shore Host But due to the Penguin fleet's last as a result, the penalty is as unique method of penalizing, the above, but the percent loss is 40. fouls had no effect on the results. Class III - If position is lost, the To Penguin Regional Their system makes fouls some• penalty is 4 points or 80% of the thing to be avoided, but not ruin- first place points whichever is the eous. It has merit from other fleets greater. Boats that foul lose their Championship Races and warrants some explaination. bonus points which are .7 of a point for first, .3 for second, and .1 for From the preparations that were For Penguins, there are three de• third. Points are scored: one for •made for it, it would seme that it grees of fouls. Class I - If the of• finishing and one for each boat fending boat does not interfere was a complete surprise to the beaten. with, or put to disadvantage any South Shore Yacht Club that the other contestant, the penalty is the After the races the 6th district 6th Regional 1951 Penguin Cham• loss of not less than two points or held a meeting at which Robert pionships were held there Sunday, 20% of the points the winning boat Pegel of the Columbia Yacht Club, receives, whichever is the greater. was elected Region Vice President October 21st. Class 11 - If the offending boat does for 1952, succeeding William F'raser Now ordinarily fanatical sailors hinder another, but the effect is of the Racine Yacht Club. -

The First Fifty Years People, Memories and Reminiscences Contents

McCrae Yacht Club – the First Fifty Years People, Memories and Reminiscences Contents Championships Hosted at McCrae ...................................................................................................2 Our champion sailors...........................................................................................................................5 Classes Sailed over the years.......................................................................................................... 12 Stories from various sailing events.............................................................................................. 25 Rescues and Tall Tales...................................................................................................................... 31 Notable personalities........................................................................................................................ 37 Did you know? – some interesting trivia.................................................................................... 43 Personal Recollections and Reminiscences .............................................................................. 46 The Little America’s Cup – what really happened ….. ............................................................ 53 McCrae Yacht Club History - firsts ................................................................................................ 58 Championships Hosted at McCrae The Club started running championships in the second year of operation. The first championships held in 1963/64 -

1960 Yearbook Excerpts

Linstead Penguin Fleet-No. 66 River Regatta and Severn Sailing Fall Series; and Jane Melvin, Gibson Island Regatta, West River Regatta, and Severn Sailing Fall Series Midget Class. Fleet Captain Tad duPont was our fleet's Junior Champion. Sandy Clark was our Midget Tom Kauffman-P.0. Box 214, Sevema Park, Md. Champion. Reet Secretary This summer, four new boats were added to our fleet and we expect to William McClure-50 Boone Trail, Sevema Park, Md. have several new ones next year. The Linstead Fleet started its spring sailing with the Annapolis Yacht Club's spring series and continued to be represented in the other Bay-area regattas throughout the rest of the season. We weren't able to take one of the first three places in the Chesapeake Bay Yacht Racing Association's high-point trophy, but we did manage to secure the fourth and fifth places. We were hosts to the opening frostbite regatta at the Severn Sailing Asso ciation's site in Annapolis. Despite the shifty and calm-to-moderate winds, all 13 participants enjoyed a keenly competitive 5-race series. We are again looking forward to a more active and highly successful forth coming year. Indian River Penguin Fleet-No. 67 The Indian River Penguin Fleet 67 has been very inactive for the past two seasons. The main reason could have been insecurity about club location. We think we have that licked with the purchase of a new up-river club location that is beautiful and perfect for Penguin races as it is in protected water (swell for frostbites). -

Championship Regatta Jeff Merrill Photos Ith All of the July Heat It Was Nice to Be Forced Into the Water, That’S What You Have to Do in Pineblock Racing

August 2014 Official Publication of Alamitos Bay Yacht Club Volume 87 • Number 8 pine blockchampionship regatta Jeff Merrill photos ith all of the July heat it was nice to be forced into the water, that’s what you have to do in Pineblock racing. It was an interesting WSunday afternoon – lightning out at sea, 90 degree plus temperatures ashore and a fickle breeze. The tide was out (preordained) and we all had to wade our turn to race in one of the most casual and liberating forms of sail boat racing available. With only 55 Pineblocks in existence (this is a worldwide number and goes back decades) it was pretty impressive to have over 20 of these sleek craft show up to race. A big thank you to ABYC’s Roberto for helping us erect our tent and stake a claim to some of the Peninsula sand for PB12 racers of all ages to hang out and have some fun. Mr. Pineblock himself, the designer and inspiration, Bob Chubb arrived on the scene and all was well in the PB world. Dressed in long pants and wearing shoes, Bob told me he wasn’t racing this year, which I accepted, after all he has never missed one, so he was due. Speaking of dues, Richard and Kelly Moffett- Higgins collected the meager $12 entry fee for annual dues and full race participation to help the fleet hopefully break even. (It’s not too late to pay your 2014 dues!) As racers arrived a few of us set up the course and practiced. -

The Economist As Plumber

The Economist as Plumber Esther Duflo ∗ 23 January 2017 Abstract As economists increasingly help governments design new policies and regulations, they take on an added responsibility to engage with the details of policy making and, in doing so, to adopt the mindset of a plumber. Plumbers try to predict as well as possible what may work in the real world, mindful that tinkering and adjusting will be necessary since our models gives us very little theoretical guidance on what (and how) details will matter. This essay argues that economists should seriously engage with plumbing, in the interest of both society and our discipline. Economists are increasingly getting the opportunity to help governments around the world design new policies and regulations. This gives them a responsibility to get the big picture, or the broad design, right. But in addition, as these designs actually get implemented in the world, this gives them the responsibility to focus on many details about which their models and theories do not give much guidance. There are two reasons for this need to attend to details. First, it turns out that policy makers rarely have the time or inclination to focus on them, and will tend to decide on how to address them based on hunches, without much regard for evidence. Figuring all of this out is therefore not something that economists can just leave to policy makers after delivering their report: if they are taking on the challenge to influence the real world, not only do they need to give general prescriptions, they must engage with the details. -

Bill Seemann – a Lifetime of Innovation

Bill Seemann – A Lifetime of Innovation William H. Seemann was born in New Orleans October 14, 1939. His father served in WWII’s Pacific Theater and subsequently went into the lumber import business. His firm, Fine Woods Company, supplied lumber to the local boat building industry. He became the first person in the area to sell fiberglass and resin, primarily to cover wooden boats. Bill actually built some models for his dad while in high school to show customers how these “new” materials could be used. Also while in high school, Bill designed and built a small powerboat using a wooden strip mold male plug by himself. Illustrating Bill’s inquisitive nature and competitive drive even as a teenager, he borrowed an outboard engine to race against a Yellow Jacket, which had an established pedigree. He won the race, returned the engine, and never used the boat again. His success in his first powerboat race did not distract Bill form his true love, which was racing small sailboats. Starting at the age of 13, he worked for a sailmaker in the summers. He mastered racing the Penguin dinghy, starting at the age of 12. Indeed, by the time he was 14 he took second place at the Penguin Nationals in Baltimore and won the regatta the next year in California. He was hooked on the sport at an early age. Bill attended Webb Institute, as he now regrets leaving after early in his second year, and then studied engineering at Tulane University in his home town. His studies there ranged from ocean engineering to psychology.