David Gribble Independent Scholar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education Revolution DOUBLE ISSUE

The Magazine of Alternative Education Education Revolution DOUBLE ISSUE I s s u e N u m b e r T h i r t y S e v e n SUMMER 2003 $4.95 USA/5.95 CDN SAY NO TO HIGH STAKES TESTING FOR KIDS Don’t Miss the IDEC! DETAILS INSIDE! w w w . e d u c a t i o n r e v o l u t i o n . o r g Education Revolution The Magazine of Alternative Educatuion Summer 2003 - Issue Number Thirty Seven - www.educationrevolution.org News What’s an IDEC? The mission of The Education Revolution magazine is based Dana Bennis................................................ 6 on that of the Alternative Education Resource Organization A Harsh Agenda (AERO): “Building the critical mass for the education Paul Wellstone..............................................7 revolution by providing resources which support self- It’s Happening All Over The World............... 7 determination in learning and the natural genius in everyone.” Towards this end, this magazine includes the latest news and David Gribble communications regarding the broad spectrum of educational alternatives: public alternatives, independent and private Being There alternatives, home education, international alternatives, and On the Bounce…………..........................9 more. The common feature in all these educational options is Street Kids……………….........................11 that they are learner-centered, focused on the interest of the child rather than on an arbitrary curriculum. Mail & Communication AERO, which produces this magazine quarterly, is firmly Main Section…………………………....... 15 established as a leader in the field of educational alternatives. News of Schools…………………………. 19 Founded in 1989 in an effort to promote learner-centered High Stakes Testing…………………….. -

Local Education by R.O

o-N BARBICAN e we LOCAL EDUCATION BY R.O. LENKIEWICZ This page left blank intentionally EXHIBITION OBSERVATIONS ON LOCAL EDUCATION R.O. LENKIEWICZ. CATALOGUE SECTION SEVENTEEN OF THE RELATIONSHIP SERIES This page left blank intentionally The Rt. Hon. Earl of St Germans Graham Carey Sam Alper Dr Dennis Waldron Dr Bran Pollard Karen Pregg Ciambriello Nick and Lou Koumbas, Barnacle Bills. Simon King THIS PROJECT OWES ITS EXISTENCE TO THE MANY KINDNESSES OF THESE PEOPLE This page left blank intentionally Throughout the work on this project, I have frequently returned to a single and overwhelming speculation; the nature of the relationship between the Adult and the Child. Education, despite all grandiose schemes, bureaucratic generalisations and cross-referential subtleties, is about this relationship. Education, as we experience it in ‘civilised’ societies is primarily concerned with the linking of human behaviour to commercial enterprise. I consider the dominant feature of education to be the mass commercial exploitation of the young. The history of human slavery is evidence of our capacity to feel no value - other than commercial value - for other human beings. Our treatment of the young is still characterised by this lack of value. We speak of the young person as ‘the future’, ‘the destiny of mankind’ a ‘spiritual investment’. Such designations are sentimental and ruthless formulas concealing the slavery referred to. It seems to me startling and eccentric to conclude that adult fear and sometimes hatred should so successfully lie hidden within educational policy. The conscription character of schooling, the effects of isolation amongst large numbers of other people, examinations, and destructive forms of competition, are patterns of control. -

15 Small Schools. INSTITUTION Human Scale Education, Bath (England)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 459 974 RC 023 307 AUTHOR Spencer, Rosalyn TITLE 15 Small Schools. INSTITUTION Human Scale Education, Bath (England). PUB DATE 1999-09-00 NOTE 50p. AVAILABLE FROM Human Scale Education, 96 Carlingcott, Nr Bath, BA2 8AW, UK (3.50 British pounds, plus 1 pound postage). E-mail: [email protected]. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Educational Environment; Educational Philosophy; *Educational Practices; Elementary Secondary Education; Environmental Education; Experiential Learning; Foreign Countries; *Nontraditional Education; *Parent Participation; *Participative Decision Making; *School Community RelationshiP; *Small Schools IDENTIFIERS Place Based Education; Sense of Community; United Kingdom ABSTRACT This report details findings from visits to 15 small schools associated with Human Scale Education. These schools are all different, reflecting the priorities of their founders. But there are features common to all of them--parental involvement, democratic processes, environmentally sustainable values, spiritual values, links with the local community, an emphasis in co-operation rather than competition, and mixed age learning. The characteristic that links them all is smallness, and it is their small size that makes possible the close relationships fundamental to good learning. By good learning, the schools mean learning in a holistic sense, encompassing the development of the creative, emotional, physical, moral, and intellectual potential of each person. Contact information, grade levels and number of students taught, and a brief history are given for each school. Educational philosophy, school-community relationships, educational practices, and grading systems are described, as well as the extent to which the national curriculum and SATs are used. Environmental education and activities, service learning, experiential activities, and exposure to the world of work are extensive. -

Changing Schools

THE EDUCATION REVOLUTION #33 Winter 2002 $4.95 The Magazine of Alternative Education www.EducationRevolution.org Nastya from Stork School in Ukraine, Artiom from England and formerly Tubelsky’s school in Russia, and Nikita from Siberia, bringing a watermelon (arbooz) back to the ship from the market. CHANGING SCHOOLS section: John Gatto: A Radically Uncivil Society Dayle Bethel: Saving Our Children, A Japanese Approach EDUCATION REVOLUTION Table of Contents NEWS Our Changing World By Albert Lamb................................................................................................................................. Wali By David Harrison........................................................................................................................................................... A Tale of Two Tests By Dana Bennis ...................................................................................................................................... The Grip is Tightening By Leonard Turton .......................................................................................................................... Eureka! It’s Adamsky! From an Interview with Alexander Adamsky................................................................................... A Democratic Youth Forum Speaks Its Mind By Jerry Mintz............................................................................................. BEING THERE With Jerry Mintz September-October: The Spirit of Learning in Hawaii............................................................................................................................................. -

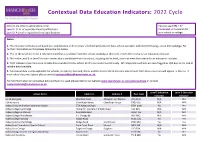

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

AERO 11 Copy

TALK AT NY OPEN CENTER Three days after getting back from the trip to the Alternative Education Conference in Boulder, I was scheduled to speak at the New York Open Center, in New York City. This was set up at the suggestion of Center Director Ralph White, who had heard about my teacher education conferences in Russia, and wanted to share information about a new center they are setting up there. Although there were not many pre-registered, I was surprised to find an overflow audience at the Center, with great interest in educational alternatives. People who attended that presentation continue to contact us almost daily. The Open Center is a non-profit Holistic Learning Center, featuring a wide variety of presentations and workshops. 83 Spring St., NY, NY 10012. 212 219-2527. FERNANDEZ, MEIER, AND RILEY AT EWA MEETING At the Education Writers Conference in Boston, I got to meet the Secretary of Education, Richard W. Riley. After he talking about the possibility of new national standards, a quasi-national curriculum, I told him that there were hundreds of thousands of homeschoolers and thousands of alternative schools that did not want a curriculum imposed on them. I asked him how he would approach that fact. He responded that "When we establish these standards they will uplift us all." I did not find that reply comforting. On the other hand, I am pleased that Madelin Kunin, former governor of Vermont, is the new Deputy Secretary of Education. She once spoke at the graduation of Shaker Mountain School when I was Headmaster, and is quite familiar with educational alternatives. -

Summer Conferences Inspire Education Activists

Changing Schools Section Special THE EDUCATION REVOLUTION The Magazine of the ALTERNATIVE EDUCATION RESOURCE ORGANIZATION (Formerly AERO-gramme) Fall 2000: $4.95 #30 www.EDREV.org IDEC IN JAPAN! (International Democratic Education Conference) Jessie Jacson Summit • New Public Alternatives Organization 900 Homeschoolers Camp at the Sea • New Gatto Book 1 CONTENTS: BIGGEST EVER IDEC HELD IN JAPAN By Ian Warder ............................................................................................... The EFFE Conference in Denmark ............................................................................................................................. 30th Annual INTERNATIONAL ALTERNATIVE EDUCATION CONFERENCE ................................................................. National Summit on Zero-Tolerance Organized by Jesse Jackson ........................................................................... Mail and Communications Edited by Carol Morley ................................................................................................... Home Education News .............................................................................................................................................. Public Alternatives, Charter School News, Other Public Alternatives ..................................................................... International News and Communications: England, Ethiopia, Germany, India, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, Nor- way, Scotland ........................................................................................................................................................... -

Eligible If Taken A-Levels at This School (Y/N)

Eligible if taken GCSEs Eligible if taken A-levels School Postcode at this School (Y/N) at this School (Y/N) 16-19 Abingdon 9314127 N/A Yes 3 Dimensions TA20 3AJ No N/A Abacus College OX3 9AX No No Abbey College Cambridge CB1 2JB No No Abbey College in Malvern WR14 4JF No No Abbey College Manchester M2 4WG No No Abbey College, Ramsey PE26 1DG No Yes Abbey Court Foundation Special School ME2 3SP No N/A Abbey Gate College CH3 6EN No No Abbey Grange Church of England Academy LS16 5EA No No Abbey Hill Academy TS19 8BU Yes N/A Abbey Hill School and Performing Arts College ST3 5PR Yes N/A Abbey Park School SN25 2ND Yes N/A Abbey School S61 2RA Yes N/A Abbeyfield School SN15 3XB No Yes Abbeyfield School NN4 8BU Yes Yes Abbeywood Community School BS34 8SF Yes Yes Abbot Beyne School DE15 0JL Yes Yes Abbots Bromley School WS15 3BW No No Abbot's Hill School HP3 8RP No N/A Abbot's Lea School L25 6EE Yes N/A Abbotsfield School UB10 0EX Yes Yes Abbotsholme School ST14 5BS No No Abbs Cross Academy and Arts College RM12 4YB No N/A Abingdon and Witney College OX14 1GG N/A Yes Abingdon School OX14 1DE No No Abraham Darby Academy TF7 5HX Yes Yes Abraham Guest Academy WN5 0DQ Yes N/A Abraham Moss Community School M8 5UF Yes N/A Abrar Academy PR1 1NA No No Abu Bakr Boys School WS2 7AN No N/A Abu Bakr Girls School WS1 4JJ No N/A Academy 360 SR4 9BA Yes N/A Academy@Worden PR25 1QX Yes N/A Access School SY4 3EW No N/A Accrington Academy BB5 4FF Yes Yes Accrington and Rossendale College BB5 2AW N/A Yes Accrington St Christopher's Church of England High School -

School Name POSTCODE AUCL Eligible If Taken GCSE's at This

School Name POSTCODE AUCL Eligible if taken GCSE's at this AUCL Eligible if taken A-levels at school this school City of London School for Girls EC2Y 8BB No No City of London School EC4V 3AL No No Haverstock School NW3 2BQ Yes Yes Parliament Hill School NW5 1RL No Yes Regent High School NW1 1RX Yes Yes Hampstead School NW2 3RT Yes Yes Acland Burghley School NW5 1UJ No Yes The Camden School for Girls NW5 2DB No No Maria Fidelis Catholic School FCJ NW1 1LY Yes Yes William Ellis School NW5 1RN Yes Yes La Sainte Union Catholic Secondary NW5 1RP No Yes School St Margaret's School NW3 7SR No No University College School NW3 6XH No No North Bridge House Senior School NW3 5UD No No South Hampstead High School NW3 5SS No No Fine Arts College NW3 4YD No No Camden Centre for Learning (CCfL) NW1 8DP Yes No Special School Swiss Cottage School - Development NW8 6HX No No & Research Centre Saint Mary Magdalene Church of SE18 5PW No No England All Through School Eltham Hill School SE9 5EE No Yes Plumstead Manor School SE18 1QF Yes Yes Thomas Tallis School SE3 9PX No Yes The John Roan School SE3 7QR Yes Yes St Ursula's Convent School SE10 8HN No No Riverston School SE12 8UF No No Colfe's School SE12 8AW No No Moatbridge School SE9 5LX Yes No Haggerston School E2 8LS Yes Yes Stoke Newington School and Sixth N16 9EX No No Form Our Lady's Catholic High School N16 5AF No Yes The Urswick School - A Church of E9 6NR Yes Yes England Secondary School Cardinal Pole Catholic School E9 6LG No No Yesodey Hatorah School N16 5AE No No Bnois Jerusalem Girls School N16 -

Institution Code Institution Title a and a Co, Nepal

Institution code Institution title 49957 A and A Co, Nepal 37428 A C E R, Manchester 48313 A C Wales Athens, Greece 12126 A M R T C ‐ Vi Form, London Se5 75186 A P V Baker, Peterborough 16538 A School Without Walls, Kensington 75106 A T S Community Employment, Kent 68404 A2z Management Ltd, Salford 48524 Aalborg University 45313 Aalen University of Applied Science 48604 Aalesund College, Norway 15144 Abacus College, Oxford 16106 Abacus Tutors, Brent 89618 Abbey C B S, Eire 14099 Abbey Christian Brothers Grammar Sc 16664 Abbey College, Cambridge 11214 Abbey College, Cambridgeshire 16307 Abbey College, Manchester 11733 Abbey College, Westminster 15779 Abbey College, Worcestershire 89420 Abbey Community College, Eire 89146 Abbey Community College, Ferrybank 89213 Abbey Community College, Rep 10291 Abbey Gate College, Cheshire 13487 Abbey Grange C of E High School Hum 13324 Abbey High School, Worcestershire 16288 Abbey School, Kent 10062 Abbey School, Reading 16425 Abbey Tutorial College, Birmingham 89357 Abbey Vocational School, Eire 12017 Abbey Wood School, Greenwich 13586 Abbeydale Grange School 16540 Abbeyfield School, Chippenham 26348 Abbeylands School, Surrey 12674 Abbot Beyne School, Burton 12694 Abbots Bromley School For Girls, St 25961 Abbot's Hill School, Hertfordshire 12243 Abbotsfield & Swakeleys Sixth Form, 12280 Abbotsfield School, Uxbridge 12732 Abbotsholme School, Staffordshire 10690 Abbs Cross School, Essex 89864 Abc Tuition Centre, Eire 37183 Abercynon Community Educ Centre, Wa 11716 Aberdare Boys School, Rhondda Cynon 10756 Aberdare College of Fe, Rhondda Cyn 10757 Aberdare Girls Comp School, Rhondda 79089 Aberdare Opportunity Shop, Wales 13655 Aberdeen College, Aberdeen 13656 Aberdeen Grammar School, Aberdeen Institution code Institution title 16291 Aberdeen Technical College, Aberdee 79931 Aberdeen Training Centre, Scotland 36576 Abergavenny Careers 26444 Abersychan Comprehensive School, To 26447 Abertillery Comprehensive School, B 95244 Aberystwyth Coll of F. -

Good News for Francisco Ferrer – How Anarchist Ideals in Education Have Survived Around the World1

10 David Gribble Good news for Francisco Ferrer – how anarchist ideals in education have survived around the world1 Introduction This chapter discusses the educational ideas of Francisco Ferrer, as expressed in his book The origin and ideals of the Modern School (1913) and compares these ideas with actual practice in anarchist schools early in the twentieth century. I suggest that a parallel movement grew up during the last century in the progres- sive or democratic schools which was in many ways closer in spirit to Ferrer than these early anarchist schools. This chapter reviews the fundamental principles of a free education before describing how these may be observed in practice in some of the many schools around the world that may be described variously as dem- ocratic, non-authoritarian, non-formal or free. The examples chosen come from many different cultures, and they differ widely from each other, but all are based on respect for the child as a person with the same rights as anyone else. In such schools, ignorant of Ferrer though they may be, many of his ideas have been proved by experience. The Modern School Education in Spain in the early 1900s had been dominated by the clergy for cen- turies. However, the times were changing. The foundation of Ferrer’s Escuela Moderna in Barcelona, and the publication of his book The origins and ideals of the Modern School led to a movement which spread rapidly through Spain and France and even reached the United States. ‘In every country,’ wrote Ferrer, ‘the governing classes, which formerly left education to the clergy, as these were quite willing to educate in a sense of obe- dience to authority, have now themselves undertaken the direction of schools’ (Ferrer, 1913: 26). -

AERO 25 Copy

HOME EDUCATION NEWS A new information resource about homeschooling has just been published, called The Homeschooling Book of Answers by Linda Dobson. The answers to 88 questions concerning education at home are answered by well-respected leaders in alternative education and by homeschoolers themselves. Among the contributors are Cafi Cohen, the Colfaxes, John Taylor Gatto, the Hegeners, Dr. Raymond Moore, and many others. Legalities, costs, special considerations, socialization, curriculum development, assessment, and the teen years are all covered in detail. The book also contains a resource list and state requirements and laws. Prima Printing, PO Box 1260BK, Rocklin, CA 95677. Tel: 916-632-4400. The revised and expanded second edition of Homeschooling in Oregon by Ann Lahrson-Fisher is now available. While it covers Oregon's state laws and requirements, the book also addresses dozens of topics of interest to all homeschoolers. It contains lists of resources broken down into subject areas; i.e., reading, computers, math, science, music, art, and so on. It is available from out of the box publishing, PO Box 80214-G, Portland, OR 97280-1214. Ron Richardson has created a new free publication called Readers Speak Out!, which gives teens an opportunity to get published. The format of this newsletter is teens' responses to questions, which cover topics in education, politics, the arts, and more. Request three sample questions from Ron at 4003 50th Ave. SW, Seattle, WA 98116. Postcard from John Taylor Gatto: "Malacca, Malaysia. Dear Jerry, What a place to change someone's perspective on the real questions about school or anything else.