David Adjaye Selects June 19, 2015 – 19, 2015 June February 7, 2016 February

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

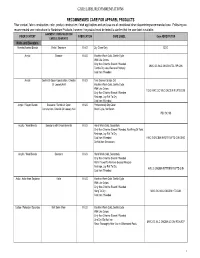

Care Label Recommendations

CARE LABEL RECOMMENDATIONS RECOMMENDED CARE FOR APPAREL PRODUCTS Fiber content, fabric construction, color, product construction, finish applications and end use are all considered when determining recommended care. Following are recommended care instructions for Nordstrom Products, however; the product must be tested to confirm that the care label is suitable. GARMENT/ CONSTRUCTION/ FIBER CONTENT FABRICATION CARE LABEL Care ABREVIATION EMBELLISHMENTS Knits and Sweaters Acetate/Acetate Blends Knits / Sweaters K & S Dry Clean Only DCO Acrylic Sweater K & S Machine Wash Cold, Gentle Cycle With Like Colors Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed MWC GC WLC ONCBIN TDL RP CIIN Tumble Dry Low, Remove Promptly Cool Iron If Needed Acrylic Gentle Or Open Construction, Chenille K & S Turn Garment Inside Out Or Loosely Knit Machine Wash Cold, Gentle Cycle With Like Colors TGIO MWC GC WLC ONCBIN R LFTD CIIN Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry Cool Iron If Needed Acrylic / Rayon Blends Sweaters / Gentle Or Open K & S Professionally Dry Clean Construction, Chenille Or Loosely Knit Short Cycle, No Steam PDC SC NS Acrylic / Wool Blends Sweaters with Embelishments K & S Hand Wash Cold, Separately Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed, No Wring Or Twist Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry Cool Iron If Needed HWC S ONCBIN NWOT R LFTD CIIN DNID Do Not Iron Decoration Acrylic / Wool Blends Sweaters K & S Hand Wash Cold, Separately Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed Roll In Towel To Remove Excess Moisture Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry HWC S ONCBIN RITTREM -

Choosing the Proper Short Cut Fiber for Your Nonwoven Web

Choosing The Proper Short Cut Fiber for Your Nonwoven Web ABSTRACT You have decided that your web needs a synthetic fiber. There are three important factors that have to be considered: generic type, diameter, and length. In order to make the right choice, it is important to know the chemical and physical characteristics of the numerous man-made fibers, and to understand what is meant by terms such as denier and denier per filament (dpf). PROPERTIES Denier Denier is a property that varies depending on the fiber type. It is defined as the weight in grams of 9,000 meters of fiber. The current standard of denier is 0.05 grams per 450 meters. Yarn is usually made up of numerous filaments. The denier of the yarn divided by its number of filaments is the denier per filament (dpf). Thus, denier per filament is a method of expressing the diameter of a fiber. Obviously, the smaller the denier per filament, the more filaments there are in the yarn. If a fairly closed, tight web is desired, then lower dpf fibers (1.5 or 3.0) are preferred. On the other hand, if high porosity is desired in the web, a larger dpf fiber - perhaps 6.0 or 12.0 - should be chosen. Here are the formulas for converting denier into microns, mils, or decitex: Diameter in microns = 11.89 x (denier / density in grams per milliliter)½ Diameter in mils = diameter in microns x .03937 Decitex = denier x 1.1 The following chart may be helpful. Our stock fibers are listed along with their density and the diameter in denier, micron, mils, and decitex for each: Diameter Generic Type -

House Dresses

L'iJA1 HJ - r a ,iwfw; . t. ,. mmmmmmmtms ' i ,1 ""."' . .,1.., j rtriiMn lis .u'.. 77ie Stere C7e5 Mjm .isriwww V7'v.tiiiz T Daily at 5 k M. Extra Trousers, $9.75 CLOTHIER double anniversary price. Smi STRAWBR1DGE & Werth this w will be the first day of our summer Suits of fine-twi- ll serge, with two pairs of roey shopping schedule. Beginning And until further notice the Stere will open at 9.00 M. and will close 6 P. M. dally. Sale A. at Anniversary years special at $1.25. H Incidentally the morning hours are the best Strawbrldee fc Clothier Second Floer, Filbert Street, Eatt K for' shopping, as they are the coolest. Thursday i: Announcements for Tomorrow w MBM m ' ' New Summer Frecks Much Wi These Wonder-Value-s in Women's. Coats and Capes Under Price in the Sale Canten Crepe Frecks, $32.50 Draped, plaited and straight-lin- e models, $15.00 $18.00 beaded and embroidered. Navy blue, black, Serges and wool veleurs. Tan Belivia weaves, wool veleurs beaver, gray, rust and white. and medium blue in Coats; tan, and tan cloaking, in loose-lin- e navy blue and black in Capes. Ceat3.. Capes of wool velour Fine Cotten Frecks, $17.50 Beautifully tailored and lined and twills nearly all lined Embroidered Dotted Swiss in navy blue, throughout. throughout. Copenhagen blue, brown, orchid and green. Im- 3& Strawbrldte Clothier Second Floer. Centre ported ginghams in blue, red, green and orchid trimmed in white. Dimities and Ginghams, $15 Dimity and fine ginghams, in tangerine, black, Misses' Dresses Under Price lavender and green. -

Mud Cloth from Mali: Its Making and Use

ISSN 0378-5254 Tydskrif vir Gesinsekologie en Verbruikerswetenskappe, Vol 31, 2003 Mud cloth from Mali: its making and use Elsje S Toerien OPSOMMING INTRODUCTION Bogolanfini van Mali, beter bekend as mud cloth, The stark, geometric, black and white designs tradi- het in die laaste aantal jare bekendheid verwerf en tionally found on the mud cloths from Mali, can today daarby ook baie gewild geraak. be found on everything from clothing and furniture to book covers and wrapping paper. Along with kente Vir baie jare was dit nie duidelik hoe hierdie kleed- (from Ghana), mud cloth has become one of the best- stof gemaak is nie. Dit was algemeen aanvaar dat known African cloth traditions worldwide (Clarke, die ontwerpe deur 'n bleikingsproses verkry is. Van- 2001). Luke-Boone (2001:8) describes it as 'probably dag is dit bekend dat die ligte ontwerpe verkry word the most influential ethnic fabric of the 1990's'. The deur hulle met donker modder te omlyn en daarna designs have indeed become an important part of the die agtergrond in te vul. Afgesien van bogolanfini se modern ethnic look found in African-inspired fashions dekoratiewe waarde, het die verskillende motiewe today. ook simboliese waarde, en word verskillende kom- binasies gebruik om 'n geskiedkundige gebeurtenis te herdenk of 'n plaaslike held te vereer. In hierdie artikel word daar gekyk na die tegnieke wat gebruik word om bogolanfini te maak, na die betekenis van sommige motiewe, en die verskillen- de maniere waarop die tegnieke of motiewe gebruik word. Die redes vir die verhoogde belangstelling in, en vervaardiging van bogolanfini word ook aange- spreek. -

Ready-Made and Custom Jeans

Have a favorite College or Pro Team or some other Summer time is nearly here and business novelty that you want to add to your shirt? casual is in the air! Ahh yes SUMMER TIME… Time to pull out those shorts, shirts, blazers, and maybe even linen pants. Wait ... we still have to work, but we can be a bit more casual and still look like a professional. What does that mean anyway? It is simple! Some might say it is a suit without a tie or maybe just that blue blazer with a pair of nice slacks. Simplicity is sophistication. Streamlining your choices, you not only make it easier on yourself, but there’s an element of confidence that comes with keeping Ready-made things unfussy. It is about buying season-appropriate clothing. When I’m talking about picking up a new and piece for this spring/summer season, I’m assuming Custom Jeans that you’ll be on the lookout for lightweight cottons Carrying ready-made and wools along with madras, linen, and seersucker. jeans, as well as These will keep you cool and sweat-free at the office, custom. out entertaining clients, or perhaps even going to a We take what you like game. from all your favorite Ok what can I wear? Invest in a few separates; a jeans and make them navy blazer, windowpane sport jackets in lighter better! colors, some mid grey, tan, or light blue trousers, and don’t cut out those jeans. Even chalk stripe jackets can spice up that casual look to show that summer’s a time for play, not just work. -

An Empirical Assessment of the Relationship Of

An International Multidisciplinary Journal, Ethiopia Vol. 7 (2), Serial No. 29, April, 2013:350-370 ISSN 1994-9057 (Print) ISSN 2070--0083 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/afrrev.7i2.22 Adire in South-western Nigeria: Geography of the Centres Areo, Margaret Olugbemisola- Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, P. M. B 4000, Ogbomoso, Nigeria E-mail; [email protected] & Kalilu, Razaq Olatunde Rom - Department of Fine and Applied Arts, Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, P. M. B 4000, Ogbomoso, Nigeria E-mail; [email protected] Abstract Adire, the patterned dyed cloth is extant and is practiced in almost all Yoruba towns in Southwestern Nigeria. The art tradition is however preponderant in a few Yoruba towns to the extent that the names of these towns are traditionally inseparable with the Adire art tradition. With Western education, introduction of foreign religions, influence from other cultures, technique and technology, there is a shift in the producers of Adire, the training pattern, and even an evolution in the production centre. While Western education resulted in a shift from the hitherto traditional Copyright© IAARR 2013: www.afrrevjo.net 350 Indexed African Journals Online: www.ajol.info Vol. 7 (2) Serial No. 29, April, 2013 Pp.350-370 apprenticeship method to the study of the art in schools, unemployment gave birth to the introduction of training drives by government and non governmental parastatals. This study, a field research, is an appraisal of the factors that contributed to the vibrancy of the traditionally renowned centres, and how the newly evolved centres have in contemporary times contributed to the sustainability of the Adire art tradition. -

Rural Dress in Southwestern Missouri Between 1860 and 1880 by Susan

Rural dress in southwestern Missouri between 1860 and 1880 by Susan E. McFarland Hooper A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Department: Textiles and Clothing Major: Textiles and Clothing Signatures have been redacted for privacy Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1976 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 SOURCES OF COSTUME, INFORMATION 4 SOUTHWESTERN MISSOURI, 1860 THROUGH 1880 8 Location and Industry 8 The Civil War 13 Evolution of the Towns and Cities 14 Rural Life 16 DEVELOPMENT OF TEXTILES AND APPAREL INDUSTRIES BY 1880 19 Textiles Industries 19 Apparel Production 23 Distribution of Goods 28 TEXTILES AND CLOTHING AVAILABLE IN SOUTHWESTERN MISSOURI 31 Goods Available from 1860 to 1866 31 Goods Available after 1866 32 CLOTHING WORN IN RURAL SOUTHWESTERN MISSOURI 37 Clothing Worn between 1860 and 1866 37 Clothing Worn between 1866 and 1880 56 SUMMARY 64 REFERENCES 66 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 70 GLOSSARY 72 iii LIST OF TABLES Page Table 1. Selected services and businesses in operation in Neosho, Missouri, 1860 and 1880 15 iv LIST OF MAPS Page Map 1. State of Missouri 9 Map 2. Newton and Jasper Counties, 1880 10 v LIST OF PHOTOGRAPHS Page Photograph 1. Southwestern Missouri family group, c. 1870 40 Photograph 2. Detail, southwestern Missouri family group, c. 1870 41 Photograph 3. George and Jim Carver, taken in Neosho, Missouri, c. 1875 46 Photograph 4. George W. Carver, taken in Neosho, Missouri, c. 1875 47 Photograph 5. Front pieces of manls vest from steamship Bertrand, 1865 48 Photograph 6. -

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Migrating Minds

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Volume 5: Issue 1 Migrating Minds AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies, University of Aberdeen JOURNAL OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH STUDIES Volume 5, Issue 1 Autumn 2011 Migrating Minds Published by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen in association with The universities of the The Irish-Scottish Academic Initiative ISSN 1753-2396 Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham and Eastbourne Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies General Editor: Cairns Craig Issue Editor: Paul Shanks Associate Editor: Michael Brown Editorial Advisory Board: Fran Brearton, Queen’s University, Belfast Eleanor Bell, University of Strathclyde Ewen Cameron, University of Edinburgh Sean Connolly, Queen’s University, Belfast Patrick Crotty, University of Aberdeen David Dickson, Trinity College, Dublin T. M. Devine, University of Edinburgh David Dumville, University of Aberdeen Aaron Kelly, University of Edinburgh Edna Longley, Queen’s University, Belfast Peter Mackay, Queen’s University, Belfast Shane Alcobia-Murphy, University of Aberdeen Ian Campbell Ross, Trinity College, Dublin Graham Walker, Queen’s University, Belfast International Advisory Board: Don Akenson, Queen’s University, Kingston Tom Brooking, University of Otago Keith Dixon, Université Lumière Lyon 2 Marjorie Howes, Boston College H. Gustav Klaus, University of Rostock Peter Kuch, University of Otago Graeme Morton, University of Guelph Brad Patterson, Victoria University, Wellington Matthew Wickman, Brigham Young David Wilson, University of Toronto The Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies is a peer reviewed journal published twice yearly in autumn and spring by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen. -

TXA News Test1.Pmd

Volume 22, Number 5 November, 2006 Contents ANNOUNCING Welcome Amy Galford Announcing CONSTANZA ONTANEDA Welcome Amy Galford 1 The Department of Textiles and Apparel welcomes Amy Galford as its newest part-time Extension Associate. Amy works with Ann Lemley to provide educational materials on Engaging Youth water quality to Cornell Cooperative Extension staff and to consumers. Her main task is the maintenance and expansion Youth Publications 2 of the water quality website with information for homeowners about drinking water, septic systems, and wells. This is not Amy’s only job. She is also a Program Assistant Intriguing Yarns 2 for the Northeastern Integrated Pest Management Center at Cornell, a program that supports research and education on pest management strategies such as crop rotation and beneficial insects and links academic, government, and private Concerning Consumers sector representatives. The Jeans Scene 2 Amy received her B.S. in Biology from Cornell University and a M.S. in Ecology from the University of Minnesota. Her past Plaid is Forever 3 jobs include training extension educators and local government officials about nonpoint source pollution issues and management options. She has also been a research Browsing Websites 3 technician in biogeochemistry at Cornell and an adjunct instructor at SUNY Cortland and Tompkins Cortland Community College. Recalling Tradition 4 One of Amy’s personal interests is working with animals. She has two dogs of her own and once considered studying veterinary medicine. She has volunteered for several animal shelters where she enjoyed walking dogs and helping people learn about animals; she currently volunteers for a border collie rescue group. -

The “African Print” Hoax: Machine Produced Textiles Jeopardize African Print Authenticity

The “African Print” Hoax: Machine Produced Textiles Jeopardize African Print Authenticity by Tunde M. Akinwumi Department of Home Science University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Nigeria Abstract The paper investigated the nature of machine-produced fabric commercially termed African prints by focusing on a select sample of these prints. It established that the general design characteristics of this print are an amalgam of mainly Javanese, Indian, Chinese, Arab and European artistic tradition. In view of this, it proposed that the prints should reflect certain aspects of Africanness (Africanity) in their design characteristics. It also explores the desirability and choice of certain design characteristics discovered in a wide range of African textile traditions from Africa south of the Sahara and their application with possible design concepts which could be generated from Macquet’s (1992) analysis of Africanity. This thus provides a model and suggestion for new African prints which might be found acceptable for use in Africa and use as a veritable export product from Africa in the future. In the commercial parlance, African print is a general term employed by the European textile firms in Africa to identify fabrics which are machine-printed using wax resins and dyes in order to achieve batik effect on both sides of the cloth, and a term for those imitating or achieving a resemblance of the wax type effects. They bear names such as abada, Ankara, Real English Wax, Veritable Java Print, Guaranteed Dutch Java Hollandis, Uniwax, ukpo and chitenge. Using the term ‘African Print’ for all the brand names mentioned above is only acceptable to its producers and marketers, but to a critical mind, the term is a misnomer and therefore suspicious because its origin and most of its design characteristics are not African. -

Meanings of Kente Cloth Among Self-Described American And

MEANINGS OF KENTE CLOTH AMONG SELF-DESCRIBED AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN STUDENTS OF AFRICAN DESCENT by MARISA SEKOLA TYLER (Under the Direction of Patricia Hunt-Hurst) ABSTRACT Little has been published regarding people of African descent’s knowledge, interpretation, and use of African clothing. There is a large disconnect between members of the African Diaspora and African culture itself. The purpose of this exploratory study was to explore the use and knowledge of Ghana’s kente cloth by African and Caribbean and American college students of African descent. Two focus groups were held with 20 students who either identified as African, Caribbean, or African American. The data showed that students use kente cloth during some special occasions, although they have little knowledge of the history of kente cloth. This research could be expanded to include college students from other colleges and universities, as well as, students’ thoughts on African garments. INDEX WORDS: Kente cloth, African descent, African American dress, ethnology, Culture and personality, Socialization, Identity, Unity, Commencement, Qualitative method, Focus group, West Africa, Ghana, Asante, Ewe, Rite of passage MEANINGS OF KENTE CLOTH AMONG SELF-DESCRIBED AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN STUDENTS OF AFRICAN DESCENT By MARISA SEKOLA TYLER B.S., North Carolina Agricultural & Technical State University, 2012 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2016 ©2016 Marisa Sekola Tyler All Rights Reserved MEANINGS OF KENTE CLOTH AMONG SELF-DESCRIBED AMERICANS AND CARIBBEAN STUDENTS OF AFRICAN DESCENT by MARISA SEKOLA TYLER Major Professor: Patricia Hunt-Hurst Committee: Tony Lowe Jan Hathcote Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2016 iv DEDICATION For Isaiah and Lydia. -

Symbolic Colors Found in African Kente Cloth (Grades K – 2)

Bold and beautiful: symbolic colors found in African Kente cloth (Grades K – 2) Procedure Introduction Have the students look closely at the clothes they are wearing, as well as any other fabrics in the classroom. Invite them to suggest how the fabrics might have been created: What materials and tools were used? Who might have made them? And so on. Ask whether fabrics and clothing are the same in other parts of the world, how they might be different, or why they may be different. Announce that they are going to learn about a very special type of fabric that was worn by kings in Africa, and point out Ghana on the map or globe in relation to the United States. The colors chosen for Kente cloths are symbolic, and a combination of colors come together to tell a story. For a full list of color symbol- ism, see background information (attached) Object-based Instruction Display the images. Guide the discussion using the following ques- tioning strategy, adapting it as desired. Include information about Kente cloth from the background material during the discussion. Akan peoples, Ghana, West Africa, Kente Cloth. Describe: What are we looking at? What colors and shapes do you see? How would you describe them? What kinds of lines are there? Time Analyze: What colors or shapes repeat? What are some patterns? 45 – 60 minutes Where do the patterns seem to change? How do you think this was made? Objectives Interpret: How do the colors in this cloth make you feel? Why do you think the weaver chose these colors? What other decisions did Students will identify, describe, create, and extend patterns using the weaver need to make while creating this piece of fabric? What lines, colors, and shapes, as they create Kente cloth designs.