Complexities of Regional and Interregional Interactions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecosystem Profile Madagascar and Indian

ECOSYSTEM PROFILE MADAGASCAR AND INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS FINAL VERSION DECEMBER 2014 This version of the Ecosystem Profile, based on the draft approved by the Donor Council of CEPF was finalized in December 2014 to include clearer maps and correct minor errors in Chapter 12 and Annexes Page i Prepared by: Conservation International - Madagascar Under the supervision of: Pierre Carret (CEPF) With technical support from: Moore Center for Science and Oceans - Conservation International Missouri Botanical Garden And support from the Regional Advisory Committee Léon Rajaobelina, Conservation International - Madagascar Richard Hughes, WWF – Western Indian Ocean Edmond Roger, Université d‘Antananarivo, Département de Biologie et Ecologie Végétales Christopher Holmes, WCS – Wildlife Conservation Society Steve Goodman, Vahatra Will Turner, Moore Center for Science and Oceans, Conservation International Ali Mohamed Soilihi, Point focal du FEM, Comores Xavier Luc Duval, Point focal du FEM, Maurice Maurice Loustau-Lalanne, Point focal du FEM, Seychelles Edmée Ralalaharisoa, Point focal du FEM, Madagascar Vikash Tatayah, Mauritian Wildlife Foundation Nirmal Jivan Shah, Nature Seychelles Andry Ralamboson Andriamanga, Alliance Voahary Gasy Idaroussi Hamadi, CNDD- Comores Luc Gigord - Conservatoire botanique du Mascarin, Réunion Claude-Anne Gauthier, Muséum National d‘Histoire Naturelle, Paris Jean-Paul Gaudechoux, Commission de l‘Océan Indien Drafted by the Ecosystem Profiling Team: Pierre Carret (CEPF) Harison Rabarison, Nirhy Rabibisoa, Setra Andriamanaitra, -

LOCALES PARA LA SEGUNDA JORNADA DE CAPACITACIÓN - Domingo 4 De Abril Línea Gratuita 0800-20-101 Presiona CONTROL + F Para Buscar Tu Local Lunes a Sábado De 7:00 A

LOCALES PARA LA SEGUNDA JORNADA DE CAPACITACIÓN - domingo 4 de abril Línea gratuita 0800-20-101 Presiona CONTROL + F para buscar tu local Lunes a sábado de 7:00 a. m. a 7:00 p. m. N° ODPE DEPARTAMENTO PROVINCIA DISTRITO CENTRO POBLADO ID LV NOMBRE DE LOCAL DIRECCION REFERENCIA 1 ABANCAY APURIMAC ABANCAY ABANCAY 0433 IE 55002 AURORA INES TEJADA JR AREQUIPA 108 PREFECTURA REGIONAL DE APURIMAC 2 ABANCAY APURIMAC ABANCAY ABANCAY 0437 IE EMBLEMATICO MIGUEL GRAU AV SEOANE 507 CERCA AL PARQUE LA CAIDA 3 ABANCAY APURIMAC ABANCAY CHACOCHE 0447 IE 54027 DANIEL DEL PINO MUÑOZ CALLE LIMA SN AL COSTADO DEL PUESTO DE SALUD 4 ABANCAY APURIMAC ABANCAY CHACOCHE CASINCHIHUA 0448 IE 54059 CASINCHIHUA AV ALAMEDA ESTUDIANTIL SN A UNA CUADRA DE LA COMISARIA 5 ABANCAY APURIMAC ABANCAY CIRCA 0440 IE N° 54016 PLAZA DE ARMAS PLAZA DE ARMAS 6 ABANCAY APURIMAC ABANCAY CIRCA LA UNION 7249 IE JOSE CARLOS MARIATEGUI CARRETERA TACCACCA AL CASTADO DE LA CARRETERA TACCACCA 7 ABANCAY APURIMAC ABANCAY CIRCA YACA-OCOBAMBA 5394 IE VARIANTE AGROPECUARIO OCOBAMBA JR OCOBAMBA CARRETERA CIRCA 8 ABANCAY APURIMAC ABANCAY CURAHUASI 0444 IE ANTONIO OCAMPO JR ANTONIO OCAMPO SN A CUATRO CUADRAS DE LA PLAZA 9 ABANCAY APURIMAC ABANCAY CURAHUASI ANTILLA 0443 IE ANTILLA MARIO VARGAS LLOSA CALLE ESCO MARCA SN CAMINO HACIA COLLPA 10 ABANCAY APURIMAC ABANCAY CURAHUASI SAN JUAN DE CCOLLPA 0442 IE 54019 CCOLLPA PLAZA DE ARMAS AL COSTADO DE LA IGLESIA 11 ABANCAY APURIMAC ABANCAY HUANIPACA 0449 IE 54030 VIRGEN DEL CARMEN JR BOLOGNESI SN AL COSTADO DE LA IGLESIA 12 ABANCAY APURIMAC ABANCAY LAMBRAMA -

AP ART HISTORY--Unit 5 Study Guide (Non Western Art Or Art Beyond the European Tradition) Ms

AP ART HISTORY--Unit 5 Study Guide (Non Western Art or Art Beyond the European Tradition) Ms. Kraft BUDDHISM Important Chronology in the Study of Buddhism Gautama Sakyamuni born ca. 567 BCE Buddhism germinates in the Ganges Valley ca. 487-275 BCE Reign of King Ashoka ca. 272-232 BCE First Indian Buddha image ca. 1-200 CE First known Chinese Buddha sculpture 338 CE First known So. China Buddha image 437 CE The Four Noble Truthsi 1. Life means suffering. Life is full of suffering, full of sickness and unhappiness. Although there are passing pleasures, they vanish in time. 2. The origin of suffering is attachment. People suffer for one simple reason: they desire things. It is greed and self-centeredness that bring about suffering. Desire is never satisfied. 3. The cessation of suffering is attainable. It is possible to end suffering if one is aware of his or her own desires and puts and end to them. This awareness will open the door to lasting peace. 4. The path to the cessation of suffering. By changing one’s thinking and behavior, a new awakening can be reached by following the Eightfold Path. Holy Eightfold Pathii The principles are • Right Understanding • Right Intention • Right Speech • Right Action • Right Livelihood • Right Effort • Right Awareness • Right Concentration Following the Eightfold Path will lead to Nirvana or salvation from the cycle of rebirth. Iconography of the Buddhaiii The image of the Buddha is distinguished in various different ways. The Buddha is usually shown in a stylized pose or asana. Also important are the 32 lakshanas or special bodily features or birthmarks. -

Major Geographic Qualities of South Asia

South Asia Chapter 8, Part 1: pages 402 - 417 Teacher Notes DEFINING THE REALM I. Major geographic qualities of South Asia - Well defined physiography – bordered by mountains, deserts, oceans - Rivers – The Ganges supports most of population for over 10,000 years - World’s 2nd largest population cluster on 3% land mass - Current birth rate will make it 1st in population in a decade - Low income economies, inadequate nutrition and poor health - British imprint is strong – see borders and culture - Monsoons, this cycle sustains life, to alter it would = disaster - Strong cultural regionalism, invading armies and cultures diversified the realm - Hindu, Buddhists, Islam – strong roots in region - India is biggest power in realm, but have trouble with neighbors - Kashmir – dangerous source of friction between 2 nuclear powers II. Defining the Realm Divided along arbitrary lines drawn by England Division occurred in 1947 and many lives were lost This region includes: Pakistan (East & West), India, Bangladesh (1971), Sri Lanka, Maldives Islands Language – English is lingua franca III. Physiographic Regions of South Asia After Russia left Afghanistan Islamic revivalism entered the region Enormous range of ecologies and environment – Himalayas, desert and tropics 1) Monsoons – annual rains that are critical to life in that part of the world 1 2) Regions: A. Northern Highlands – Himalayas, Bhutan, Afghanistan B. River Lowlands – Indus Valley in Pakistan, Ganges Valley in India, Bangladesh C. Southern Plateaus – throughout much of India, a rich -

Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the Country

ARCTIC OCEAN RUSSIA JAPAN KAZAKHSTAN NORTH MONGOLIA KOREA UZBEKISTAN SOUTH TURKMENISTAN KOREA KYRGYZSTAN TAJIKISTAN PACIFIC Jammu and AFGHANIS- Kashmir CHINA TAN OCEAN PAKISTAN TIBET Taiwan NEPAL BHUTAN BANGLADESH Hong Kong INDIA BURMA LAOS PHILIPPINES THAILAND VIETNAM CAMBODIA Andaman and Nicobar BRUNEI SRI LANKA Islands Bougainville MALAYSIA PAPUA NEW SOLOMON ISLANDS MALDIVES GUINEA SINGAPORE Borneo Sulawesi Wallis and Futuna (FR.) Sumatra INDONESIA TIMOR-LESTE FIJI ISLANDS French Polynesia (FR.) Java New Caledonia (FR.) INDIAN OCEAN AUSTRALIA NEW ZEALAND Asia and Oceania Nicole Girard, Irwin Loy, Marusca Perazzi, Jacqui Zalcberg the country. However, this doctrine is opposed by nationalist groups, who interpret it as an attack on ethnic Kazakh identity, language and Central culture. Language policy is part of this debate. The Asia government has a long-term strategy to gradually increase the use of Kazakh language at the expense Matthew Naumann of Russian, the other official language, particularly in public settings. While use of Kazakh is steadily entral Asia was more peaceful in 2011, increasing in the public sector, Russian is still with no repeats of the large-scale widely used by Russians, other ethnic minorities C violence that occurred in Kyrgyzstan and many urban Kazakhs. Ninety-four per cent during the previous year. Nevertheless, minor- of the population speak Russian, while only 64 ity groups in the region continue to face various per cent speak Kazakh. In September, the Chair forms of discrimination. In Kazakhstan, new of the Kazakhstan Association of Teachers at laws have been introduced restricting the rights Russian-language Schools reportedly stated in of religious minorities. Kyrgyzstan has seen a a roundtable discussion that now 56 per cent continuation of harassment of ethnic Uzbeks in of schoolchildren study in Kazakh, 33 per cent the south of the country, and pressure over land in Russian, and the rest in smaller minority owned by minority ethnic groups. -

Locales De Votación Al 17-01-2020

LOCALES DE VOTACIÓN AL VIERNES 17 DE ENERO DE 2020 Llámanos gratis al 0800-79-100 Todos los días de 06:00 hasta 22:00 horas Presiona CONTROL + F para buscar tu local. N° ODPE NOMBRE ODPE SEDE DE ODPE UBIGEO DEPARTAMENTO PROVINCIA DISTRITO ID LOCAL NOMBRE DEL LOCAL DIRECCIÓN DEL LOCAL MESAS ELECTORES CCPP TIPO TECNOLOGÍA VRAEM 1 1 BAGUA BAGUA 010201 AMAZONAS BAGUA LA PECA 0025 IE 16281 AV. BAGUA SN 1 104 ESPITAL CON 2 1 BAGUA BAGUA 010201 AMAZONAS BAGUA LA PECA 0026 IE 16277 JR. PROGRESO SN 1 147SAN ISIDRO CON 3 1 BAGUA BAGUA 010201 AMAZONAS BAGUA LA PECA 0027 IE 31 NUESTRA SEÑORA DE GUADALUPE - FE Y ALEGRIA JR. MARAÑÓN SN 15 4243 CON 4 1 BAGUA BAGUA 010201 AMAZONAS BAGUA LA PECA 0028 IE 16275 AV. SAN FELIPE N° 486 8 2237 CON 5 1 BAGUA BAGUA 010201 AMAZONAS BAGUA LA PECA 0029 IE 16279 AV. LA FLORIDA SN 2 312ARRAYAN CON 6 1 BAGUA BAGUA 010201 AMAZONAS BAGUA LA PECA 0030 IE 16283 AV. CORONEL BENITES SN 1 184 CHONZA ALTA CON 7 1 BAGUA BAGUA 010201 AMAZONAS BAGUA LA PECA 5961 IE 16288 AV. ATAHUALPA SN 2 292SAN FRANCISCO CON 8 1 BAGUA BAGUA 010202 AMAZONAS BAGUA ARAMANGO 0032 IE MIGUEL MONTEZA TAFUR AV. 28 DE JULIO SN 8 2402 SEA 9 1 BAGUA BAGUA 010202 AMAZONAS BAGUA ARAMANGO 0033 IE 16201 AV. 28 DE JULIO SN 18 5990 SEA 10 1 BAGUA BAGUA 010203 AMAZONAS BAGUA COPALLIN 0034 IE 16239 JR. RODRIGUEZ DE MENDOZA N° 651 15 4142 CON 11 1 BAGUA BAGUA 010204 AMAZONAS BAGUA EL PARCO 0035 IE 16273 JR. -

Albania's 'Sworn Virgins'

THE LINGUISTIC EXPRESSION OF GENDER IDENTITY: ALBANIA’S ‘SWORN VIRGINS’ CARLY DICKERSON A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN LINGUISTICS YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO August 2015 © Carly Dickerson, 2015 Abstract This paper studies the linguistic tools employed in the construction of masculine identities by burrneshat (‘sworn virgins’) in northern Albania: biological females who have become ‘social men’. Unlike other documented ‘third genders’ (Kulick 1999), burrneshat are not motivated by considerations of personal identity or sexual desire, but rather by the need to fulfill patriarchal roles within a traditional social code that views women as property. Burrneshat are thus seen as honourable and self-sacrificing, are accepted as men in their community, and are treated accordingly, except that they do not marry or engage in sexual relationships. Given these unique circumstances, how do the burrneshat construct and express their identity linguistically, and how do others within the community engage with this identity? Analysis of the choices of grammatical gender in the speech of burrneshat and others in their communities indicates both inter- and intra-speaker variation that is linked to gendered ideologies. ii Table of Contents Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………………….. ii Table of Contents ……………………………………………………………………………….. iii List of Tables …………………………………………………………………………..……… viii List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………………………ix Chapter One – Introduction ……………………………………………………………………... 1 Chapter Two – Albanian People and Language ………………………………………………… 6 2.0 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………6 2.1 History of Albania ………………………………………………………………………..6 2.1.1 Geographical Location ……………………………………………………………..6 2.1.2 Illyrian Roots ……………………………………………………………………….7 2.1.3 A History of Occupations …………………………………………………………. 8 2.1.4 Northern Albania …………………………………………………………………. -

Pdf/77-Wrvw-272.Pdf

H-ART. Revista de historia, teoría y crítica de arte ISSN: 2539-2263 ISSN: 2590-9126 [email protected] Universidad de Los Andes Colombia Ambrosino, Gordon Inscription, Place, and Memory: Palimpsest Rock Art and the Evolution of Highland, Andean Social Landscapes in the Formative Period (1500 – 200 BC) H-ART. Revista de historia, teoría y crítica de arte, no. 5, 2019, July-, pp. 127-156 Universidad de Los Andes Colombia DOI: https://doi.org/10.25025/hart05.2019.07 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=607764857003 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Inscription, Place, and Memory: Palimpsest Rock Art and the Evolution of Highland, Andean Social Landscapes in the Formative Period (1500 – 200 BC) Inscripción, lugar y memoria: arte rupestre palimpsesto y la evolución de los paisajes sociales andinos en las tierras altas durante el Período Formativo (1500 - 200 a. C.) Inscrição, local e memória: arte de uma roca palimpsesto e a evolução das paisagens sociais andinas durante o Período Formativo (1500 - 200 a. e. c.) Received: January 27, 2019. Accepted: April 12, 2019. Modifications: April 24, 2019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.25025/hart05.2019.07 Gordon Ambrosino Abstract Mellon Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow, Los Angeles As more than a means of recalling, memory is an active County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, Art of the Ancient cultural creation and landscape inscriptions construct Americas Department. -

Of Coastal Ecuador

WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY Department of Anthropology Dissertation Examination Committee: David L. Browman, Chair Gwen Bennett Gayle Fritz Fiona Marshall T.R. Kidder Karen Stothert TECHNOLOGY, SOCIETY AND CHANGE: SHELL ARTIFACT PRODUCTION AMONG THE MANTEÑO (A.D. 800-1532) OF COASTAL ECUADOR by Benjamin Philip Carter A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2008 Saint Louis, Missouri Copyright by Benjamin Philip Carter © 2008 ii Acknowledgments For this research, I acknowledge the generous support of the National Science Foundation for a Dissertation Improvement Grant (#0417579) and Washington University for a travel grant in 2000. This dissertation would not exist without the support of many, many people. Of course, no matter how much they helped me, any errors that remain are mine alone. At Drew University, Maria Masucci first interested me in shell bead production and encouraged me to travel first to Honduras and then to Ecuador. Without her encouragement and support, I would not have begun this journey. In Honduras, Pat Urban and Ed Schortman introduced me to the reality of archaeological projects. Their hard- work and scholarship under difficult conditions provided a model that I hope I have followed and will continue to follow. While in Honduras, I was lucky to have the able assistance of Don Luis Nolasco, Nectaline Rivera, Pilo Borjas, and Armando Nolasco. I never understood why the Department of Anthropology at Washington University in St. Louis accepted me into their program, but I hope that this document is evidence that they made the right choice. -

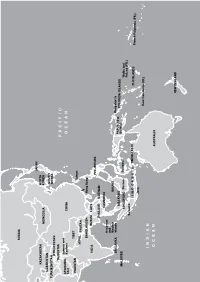

Japanese Researchon Andean Prehistory

JapaneseJapaneseSociety Society of Cultural Anthropology Japanese Review of Culturat AnthropolDgy, vol.3, 2002 Japanese Research on Andean Prehistory ONuKI Yoshio The Little World Museum of Man Abstract The study of Andean prehistory by Japanese anthropologists began in 1958 when the first scientific expedition was carried out. The principal objective ofthis project was research on the origins ofAndean civilization. The project has continued for over 45 years, and many Japanese specialists have partieipated in it. They have not only excavated more than ten archaeological sites in Peru, but have also made many contributions to the advancement of Andean prehistorM both in data and theory, This article summarizes the history of this research in relation to theoretical trends in the discipline, and ends with some comments about the relationship between the researchers and the local people. Key words: Andean archaeology; Peruvian prehistory; Formative period; Kotosh; Kuntur Wasi; origins of civilization; Andean civilization; Chavin The Beginning In 1937, [Ibrii Ryuzo (1870-1953) was sent to Brazil as a cultural envoy by the Japanese government. After completing this mission, he made a trip to Peru and Bolivia to become acquainted with the many archaeological sites and materials to be found there. There is no doubt that he was fascinated by prehistoric Andean civilization, and he began to find out about it by visiting archaeological sites, by meeting Peruvian and Bolivian archaeologists, and also by reading seme of the literature available at that time. He met Julio C. [[bllo at an excavation at the Cerro Sechin site, on the Central Coast of Peru, after which he visited Chan Chan on the NII-Electronic Library Service JapaneseJapaneseSociety Society ofCulturalof Cultural Anthropology 58 ONuKIY]shio North Coast, Here he got to know Rafael Larco Hoyle, and learned about the dispute between these two pioneers ef Peruvian archaeology over the origins ofthe Andean civilization. -

As the Psychoactive Plant Utilized at Chavín De Huántar

Ñawpa Pacha Journal of Andean Archaeology ISSN: 0077-6297 (Print) 2051-6207 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ynaw20 What kind of hallucinogenic snuff was used at Chavín de Huántar? An iconographic identification Richard Burger To cite this article: Richard Burger (2011) What kind of hallucinogenic snuff was used at Chavín de Huántar? An iconographic identification, Ñawpa Pacha, 31:2, 123-140, DOI: 10.1179/ naw.2011.31.2.123 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1179/naw.2011.31.2.123 Published online: 19 Jul 2013. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 196 Citing articles: 3 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ynaw20 What kind of hallucinogenic snuff was used at Chavín de Huántar? An iconographic identification Richard L. Burger Iconography and artifacts from Chavín de Huántar attest to the importance of psychoactive substances consumed na- sally as snuff, and consequently hallucinogens other than San Pedro cactus must have been utilized. This article presents iconographic evidence from a Chavín de Huántar sculpture demonstrating the religious significance of Anadenanthera sp. (vilca), a plant containing the vision-producing bufotenine. Andenanthera colubrina var. Cebil is found east of the Peruvian Andes and consequently it is the most likely source of the psychoactive snuff ingested in the rituals at Chavín de Huántar and related ceremonial centers such as Kuntur Wasi. Aunque la utilización de substancias alucinógenas en el templo de Chavín de Huántar durante el fin del Período Inicial y el Horizonte Temprano (1000–300 a.C.) ha recibido la amplia aceptación de los arqueólogos, la única identificación de una droga alucinógena ha sido el San Pedro (Trichocereus pachanoi), un cactus rico en mescalina que hoy se encuentra en la costa y la sierra, incluyendo los alrededores de Chavín de Huántar. -

Libro 8 Institucional Copia Correjido

CONTEXTO DEL DESARROLLO DE CAJAMARCA: ¿CÓMO HACER VIABLE A CAJAMARCA? 1 2 CAJAMARCA: LINEAMIENTOS PARA UNA POLÍTICA DE FORTALECIMIENTO INSTITUCIONAL CONTEXTO DEL DESARROLLO DE CAJAMARCA: ¿CÓMO HACER VIABLE A CAJAMARCA? 3 4 CAJAMARCA: LINEAMIENTOS PARA UNA POLÍTICA DE FORTALECIMIENTO INSTITUCIONAL © Primera edición: julio 2006 Asociación Los Andes de Cajamarca Jr. Jequetepeque 776 Urb. El Ingenio Cajamarca, Perú www.losandes.org.pe Contribuciones para una visión del desarrollo de Cajamarca Editor: Francisco Guerra García Volumen 8 Cajamarca: Lineamientos para una política de fortalecimiento institucional Cecilia Balcázar Suárez Corrección: Luis Cueva Diagramación e Impresión: Visual Service Hecho el Depósito Legal en la Biblioteca Nacional del Perú Nº: 2006-5469 Los contenidos de este documento pueden ser reproducidos en su totalidad o en parte en cualquier medio, citando la fuente. CONTEXTO DEL DESARROLLO DE CAJAMARCA: ¿CÓMO HACER VIABLE A CAJAMARCA? 5 A los maestros y alumnos del Colegio Nacional San Ramón de Cajamarca en su 175° Aniversario. 6 CAJAMARCA: LINEAMIENTOS PARA UNA POLÍTICA DE FORTALECIMIENTO INSTITUCIONAL CONTEXTO DEL DESARROLLO DE CAJAMARCA: ¿CÓMO HACER VIABLE A CAJAMARCA? 7 PRESENTACIÓN El trabajo que ahora presentamos es parte de un proyecto orientado a contribuir al logro de una visión de desarrollo de la región de Cajamarca. El proyecto consistió en la realización de diez consultorías sobre temas económicos y sociales a cargo de otros tantos expertos de reconocida solvencia profesional: Cajamarca: El proceso demográfico