Reading of Race in the History Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black History Month February 2020

BLACK HISTORY MONTH FEBRUARY 2020 LITERARY FINE ARTS MUSIC ARTS Esperanza Rising by Frida Kahlo Pam Munoz Ryan Frida Kahlo and Her (grades 3 - 8) Animalitos by Monica Brown and John Parra What Can a Citizen Do? by Dave Eggers and Shawn Harris (K-2) MATH & CULINARY HISTORY SCIENCE ARTS BLACK HISTORY MONTH FEBRUARY 2020 FINE ARTS Alma Thomas Jacob Lawrence Faith Ringgold Alma Thomas was an Faith Ringgold works in a Expressionist painter who variety of mediums, but is most famous for her is best-known for her brightly colored, often narrative quilts. Create a geometric abstract colorful picture, leaving paintings composed of 1 or 2 inches empty along small lines and dot-like the edge of your paper marks. on all four sides. Cut colorful cardstock or Using Q-Tips and primary Jacob Lawrence created construction paper into colors, create a painted works of "dynamic squares to add a "quilt" pattern in the style of Cubism" inspired by the trim border to your Thomas. shapes and colors of piece. Harlem. His artwork told stories of the African- American experience in the 20th century, which defines him as an artist of social realism, or artwork based on real, modern life. Using oil pastels and block shapes, create a picture from a day in your life at school. What details stand out? BLACK HISTORY MONTH FEBRUARY 2020 MUSIC Creating a Music important to blues music, and pop to create and often feature timeless radio hits. Map melancholy tales. Famous Famous Motown With your students, fill blues musicians include B.B. -

Honorary Degree Recipients 1977 – Present

Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Claire Collins Harvey, C‘37 Harry Belafonte 1977 Patricia Roberts Harris Katherine Dunham 1990 Toni Morrison 1978 Nelson Mandela Marian Anderson Marguerite Ross Barnett Ruby Dee Mattiwilda Dobbs, C‘46 1979 1991 Constance Baker Motley Miriam Makeba Sarah Sage McAlpin Audrey Forbes Manley, C‘55 Mary French Rockefeller 1980 Jesse Norman 1992 Mabel Murphy Smythe* Louis Rawls 1993 Cardiss Collins Oprah Winfrey Effie O’Neal Ellis, C‘33 Margaret Walker Alexander Dorothy I. Height 1981 Oran W. Eagleson Albert E. Manley Carol Moseley Braun 1994 Mary Brookins Ross, C‘28 Donna Shalala Shirley Chisholm Susan Taylor Eleanor Holmes Norton 1982 Elizabeth Catlett James Robinson Alice Walker* 1995 Maya Angelou Elie Wiesel Etta Moten Barnett Rita Dove Anne Cox Chambers 1983 Myrlie Evers-Williams Grace L. Hewell, C‘40 Damon Keith 1996 Sam Nunn Pinkie Gordon Lane, C‘49 Clara Stanton Jones, C‘34 Levi Watkins, Jr. Coretta Scott King Patricia Roberts Harris 1984 Jeanne Spurlock* Claire Collins Harvey, C’37 1997 Cicely Tyson Bernice Johnson Reagan, C‘70 Mary Hatwood Futrell Margaret Taylor Burroughs Charles Merrill Jewel Plummer Cobb 1985 Romae Turner Powell, C‘47 Ruth Davis, C‘66 Maxine Waters Lani Guinier 1998 Gwendolyn Brooks Alexine Clement Jackson, C‘56 William H. Cosby 1986 Jackie Joyner Kersee Faye Wattleton Louis Stokes Lena Horne Aurelia E. Brazeal, C‘65 Jacob Lawrence Johnnetta Betsch Cole 1987 Leontyne Price Dorothy Cotton Earl Graves Donald M. Stewart 1999 Selma Burke Marcelite Jordan Harris, C‘64 1988 Pearl Primus Lee Lorch Dame Ruth Nita Barrow Jewel Limar Prestage 1989 Camille Hanks Cosby Deborah Prothrow-Stith, C‘75 * Former Student As of November 2019 Board of Trustees HONORARY DEGREE RECIPIENTS 1977 – PRESENT Name Year Awarded Name Year Awarded Max Cleland Herschelle Sullivan Challenor, C’61 Maxine D. -

Nytimes Black History Month Is a Good Excuse for Delving Into Our

Black History Month Is a Good Excuse for Delving Into Our Art An African-American studies professor suggests ways to mark the month, from David Driskell’s paintings and Dance Theater of Harlem’s streamed performances to the rollicking return of “Queen Sugar.” David Driskell’s “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” (1972), acrylic on canvas. Estate of David C. Driskell and DC Moore Gallery By Salamishah Tillet • Feb. 18, 2021 Black History Month feels more urgent this year. Its roots go back to 1926, when the historian Carter G. Woodson developed Negro History Week, near the February birthdays of both President Abraham Lincoln and the abolitionist Frederick Douglass, in the belief that new stories of Black life could counter old racist stereotypes. Now in this age of racial reckoning and social distancing, our need to connect with each other has never been greater. As a professor of African-American studies, I am increasingly animated by the work of teachers who have updated Woodson’s goal for the 21st century. Just this week, my 8- year-old daughter showed me a letter written by her entire 3rd-grade art class to Faith Ringgold, the 90-year-old African-American artist. And my son told me about a recent pre-K lesson on Ruby Bridges, the first African-American student who, at 6, integrated an elementary school in the South. Suddenly, the conversations my kids have at home with my husband and me are the ones they’re having in their classrooms. It's not just their history that belongs in all these spaces, but their knowledge, too. -

African American Creative Arts Dance, Literature, Music, Theater, and Visual Art from the Great Depression to Post-Civil Rights Movement of the 1960S

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 6, No. 2; February 2016 African American Creative Arts Dance, Literature, Music, Theater, and Visual Art From the Great Depression to Post-Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s Dr. Iola Thompson, Ed. D Medgar Evers College, CUNY 1650 Bedford Ave., Brooklyn, NY 11225 USA Abstract The African American creative arts of dance, music, literature, theater and visual art continued to evolve during the country’s Great Depression due to the Stock Market crash in 1929. Creative expression was based, in part, on the economic, political and social status of African Americans at the time. World War II had an indelible impact on African Americans when they saw that race greatly affected their treatment in the military while answering the patriotic call like white Americans. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s had the greatest influence on African American creative expression as they fought for racial equality and civil rights. Artistic aesthetics was based on the ideologies and experiences stemming from that period of political and social unrest. Keywords: African American, creative arts, Great Depression, WW II, Civil Rights Movement, 1960s Introduction African American creative arts went through several periods of transition since arriving on the American shores with enslaved Africans. After emancipation, African characteristics and elements began to change as the lifestyle of African Americans changed. The cultural, social, economic, and political vicissitudes caused the creative flow and productivity to change as well. The artistic community drew upon their experiences as dictated by various time periods, which also created their ideologies. During the Harlem Renaissance, African Americans experienced an explosive period of artistic creativity, where the previous article left off. -

Diversity in the Arts

Diversity In The Arts: The Past, Present, and Future of African American and Latino Museums, Dance Companies, and Theater Companies A Study by the DeVos Institute of Arts Management at the University of Maryland September 2015 Authors’ Note Introduction The DeVos Institute of Arts Management at the In 1999, Crossroads Theatre Company won the Tony Award University of Maryland has worked since its founding at the for Outstanding Regional Theatre in the United States, the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in 2001 to first African American organization to earn this distinction. address one aspect of America’s racial divide: the disparity The acclaimed theater, based in New Brunswick, New between arts organizations of color and mainstream arts Jersey, had established a strong national artistic reputation organizations. (Please see Appendix A for a list of African and stood as a central component of the city’s cultural American and Latino organizations with which the Institute revitalization. has collaborated.) Through this work, the DeVos Institute staff has developed a deep and abiding respect for the artistry, That same year, however, financial difficulties forced the passion, and dedication of the artists of color who have theater to cancel several performances because it could not created their own organizations. Our hope is that this project pay for sets, costumes, or actors.1 By the following year, the will initiate action to ensure that the diverse and glorious quilt theater had amassed $2 million in debt, and its major funders that is the American arts ecology will be maintained for future speculated in the press about the organization’s viability.2 generations. -

National Endowment for the Arts Annual Report 1993

L T 1 TO THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES: It is my special pleasure to transmit herewith the Annual Report of the National Endowment for the Arts for the fiscal year 1993. The National Endowment for the Arts has awarded over 100,000 grants since 1965 for arts projects that touch every community in the Nation. Through its grants to individual artists, the agency has helped to launch and sustain the voice and grace of a generation--such as the brilliance of Rita Dove, now the U.S. Poet Laureate, or the daring of dancer Arthur Mitchell. Through its grants to art organizations, it has helped invigorate community arts centers and museums, preserve our folk heritage, and advance the perform ing, literary, and visual arts. Since its inception, the Arts Endowment has believed that all children should have an education in the arts. Over the past few years, the agency has worked hard to include the arts in our national education reform movement. Today, the arts are helping to lead the way in renewing American schools. I have seen first-hand the success story of this small agency. In my home State of Arkansas, the National Endowment for the Arts worked in partnership with the State arts agency and the private sector to bring artists into our schools, to help cities revive downtown centers, and to support opera and jazz, literature and music. All across the United States, the Endowment invests in our cultural institutions and artists. People in communities small and large in every State have greater opportunities to participate and enjoy the arts. -

The National Arts Awards Chair

1 Edye and Eli Broad salute Americans for the Arts and 2 tonight’s honorees for their commitment ensuring broad access to the arts 2014 Americans for the Arts National Arts Awards Monday, October 20, 2014 Welcome from Robert L. Lynch Performance by YoungArts Alumni President and CEO of Americans for the Arts Outstanding Contributions to the Arts Award Legacy Award American Legion Auxiliary Madeleine H. Berman Presented by Nolen V. Bivens, Presented by Anne Parsons Brigadier General, U.S. Army, (Ret) Accepted by Janet Jefford Lifetime Achievement Award Richard Serra Eli and Edythe Broad Award for 3 Presented by Jennifer Russell Philanthropy in the Arts Vicki and Roger Sant Arts Education Award Presented by The Honorable Christopher J. Dodd P.S. ARTS Presented by Ben Stiller Bell Family Foundation Young Artist Award Accepted by Joshua B. Tanzer David Hallberg Presented by RoseLee Goldberg Dinner Closing Remarks Robert L. Lynch introduction of Maria Bell Abel Lopez, Chair, Americans for the Arts Vice Chairman, Americans for the Arts Board of Board of Directors Directors and Chair, National Arts Awards and Robert L. Lynch Greetings from the Board Chair and President It is our pleasure to welcome you to our annual Americans for the Arts National Arts Awards. Tonight we again celebrate a select group of cultural leaders— groundbreaking artists, visionary philanthropists, and two outstanding nonprofit organizations—who help ensure that every American has access to the transformative power of the arts. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of all of our honorees. In this time of increasing challenges to our nation’s security and the sacrifices made by our servicemen and women and their families, we are especially pleased to recognize the American Legion Auxiliary, one of our many partners in the work we do with the military and veterans on the role of the arts & healing. -

History, Labor, Life: the Prints of Jacob Lawrence OCT

CURRICULUM GUIDE GRADES K- 12 History, Labor, Life: The Prints of Jacob Lawrence OCT. 14, 2015 - JAN. 25, 2016 SCAD: The University for Creative Careers The Savannah College of Art and Design is a private, nonprofit, accredited institution conferring bachelor’s and master’s degrees at distinctive locations and online to prepare talented students for professional careers. SCAD offers degrees in more than 40 majors, as well as minors in more than 75 disciplines across its locations in Savannah and Atlanta, Georgia; in Hong Kong; in Lacoste, France; and online through SCAD eLearning. With more than 35,000 alumni worldwide, SCAD demonstrates an exceptional education and unparalleled career preparation. The diverse student body, consisting of nearly 14,000, comes from across the U.S. and more than 100 countries worldwide. Each student is nurtured and motivated by a faculty of nearly 700 professors with extraordinary academic credentials and valuable professional experience. These professors emphasize learning through individual attention in an inspiring university environment. The innovative SCAD curriculum is enhanced by advanced professional-level technology, equipment and learning resources, and has garnered acclaim from respected organizations and publications, including 3D World, American Institute of Architects, Businessweek, DesignIntelligence, U.S. News & World Report and the Los Angeles Times. For more information, visit scad.edu. a Cover Image: Jacob Lawrence, The Builders (Family), 1974 Table of Contents About the SCAD Museum of -

NEA Chronology Final

THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS 1965 2000 A BRIEF CHRONOLOGY OF FEDERAL SUPPORT FOR THE ARTS President Johnson signs the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act, establishing the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, on September 29, 1965. Foreword he National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act The thirty-five year public investment in the arts has paid tremen Twas passed by Congress and signed into law by President dous dividends. Since 1965, the Endowment has awarded more Johnson in 1965. It states, “While no government can call a great than 111,000 grants to arts organizations and artists in all 50 states artist or scholar into existence, it is necessary and appropriate for and the six U.S. jurisdictions. The number of state and jurisdic the Federal Government to help create and sustain not only a tional arts agencies has grown from 5 to 56. Local arts agencies climate encouraging freedom of thought, imagination, and now number over 4,000 – up from 400. Nonprofit theaters have inquiry, but also the material conditions facilitating the release of grown from 56 to 340, symphony orchestras have nearly doubled this creative talent.” On September 29 of that year, the National in number from 980 to 1,800, opera companies have multiplied Endowment for the Arts – a new public agency dedicated to from 27 to 113, and now there are 18 times as many dance com strengthening the artistic life of this country – was created. panies as there were in 1965. -

QR Codes ONLY

QR Codes ONLY IF you have already assembled your Periodic Table, you can print and laminate these QR codes and attach them to your Periodic Table. 1 Benjamin Banneker 3 Frederick Douglass 11 Medgar Evers 19 Fannie Lou Hamer 37 Martin Luther 55 Mary McLeod 73 Rosa Parks 4 Marian Anderson King Jr. Bethune 12 Misty Copeland 20 Dr. Mae Jemison 38 Robert Louis 56 Simone Manuel Johnson 74 Thurgood 21 Tomi Adeyemi 22 Kwame Alexander 23 Maya Angelou Marshall 24 James Baldwin 25 Octavia Butler 26 Lucille Clifton 27 Ta-Nehisi Coates 28 Ralph Ellison 29 Roxane Gay 39 Langston Hughes 40 Zora Neale Hurston 41 Nella Larsen 42 Audre Lorde 43 Toni Morrison 44 Jason Reynolds 45 Alice Walker 46 Phillis Wheatley 47 Colson 64 Jacqueline Whitehead Woodson 65 Richard Wright 57 Muhammad Ali 58 Simone Biles 60 Lebron James 59 Michael Jordan 61 Jesse Owens 62 Jackie Robinson 63 Venus & Serena Williams 75 Louis Armstrong 76 Chuck Berry 77 Beyonce 78 Aretha Franklin 79 Donald Glover 80 Prince 81 Esperanza 30 Halle Berry Spalding 13 Josephine Baker 31 Laverne Cox 48 Morgan Freeman 49 Whoopi Goldberg 50 James Earl Jones 66 Nichelle Nichols 67 Sidney Poitier 68 Issa Rae 69 Will Smith 70 Denzel 5 Blanche Bruce 14 Shirley Chisholm Washington 32 Barbara Jordan 33 John Lewis 51 Carrie Meek 52 Barack Obama 71 Frederica Wilson 6 David Blackwell 7 Edward Bouchet 8 Otis Boykin 9 Alexa Canady 15 George Carruthers 16 Annie Easley 17 Marie Maynard Daly 34 George 35 Betty Washington 53 Roger Arliner 2 George Foreman Washington Carver Greene Young 10 Jay-Z 18 Garrett Morgan 36 Annie Turnbo 54 Madam CJ Walker Malone 72 Oprah Winfrey 82 Alvin Ailey 83 Jean-Michel 84 Jacob Lawrence Basquiat 85 Arthur Mitchell 86 Amy Sherald 87 Alma Woodsey 88 James VanDerZee Thomas 89 Kehinde Wiley 90 Kara Walker Sources: • Biography.com, A&E Networks Television, www.biography.com/. -

1 Preserving the Legacy the Hotel

PRESERVING THE LEGACY THE HOTEL PONCE DE LEON AND FLAGLER COLLEGE By LESLEE F. KEYS A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2013 1 © 2013 Leslee F. Keys 2 To my maternal grandmother Lola Smith Oldham, independent, forthright and strong, who gave love, guidance and support to her eight grandchildren helping them to pursue their dreams. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS My sincere appreciation is extended to my supervisory committee for their energy, encouragement, and enthusiasm: from the College of Design, Construction and Planning, committee chair Christopher Silver, Ph.D., FAICP, Dean; committee co-chair Roy Eugene Graham, FAIA, Beinecke-Reeves Distinguished Professor; and Herschel Shepard, FAIA, Professor Emeritus, Department of Architecture. Also, thanks are extended to external committee members Kathleen Deagan, Ph.D., Distinguished Research Professor Emeritus of Anthropology, Florida Museum of Natural History and John Nemmers, Archivist, Smathers Libraries. Your support and encouragement inspired this effort. I am grateful to Flagler College and especially to William T. Abare, Jr., Ed.D., President, who championed my endeavor and aided me in this pursuit; to Michael Gallen, Library Director, who indulged my unusual schedule and persistent requests; and to Peggy Dyess, his Administrative Assistant, who graciously secured hundreds of resources for me and remained enthusiastic over my progress. Thank you to my family, who increased in number over the years of this project, were surprised, supportive, and sources of much-needed interruptions: Evan and Tiffany Machnic and precocious grandsons Payton and Camden; Ethan Machnic and Erica Seery; Lyndon Keys, Debbie Schmidt, and Ashley Keys. -

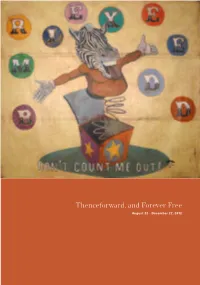

Thenceforward, and Forever Free August 22 - December 22, 2012 2

1 1 Thenceforward, and Forever Free August 22 - December 22, 2012 2 Cover image Michael Ray Charles American, b. 1967 (Forever Free) Mixed Breed, 1997 Acrylic latex, stain and copper penny on canvas tarp 99 x 111" Collection of Tony Shafrazi Gallery, New York 3 Thenceforward, and Forever Free August 22 - December 22, 2012 Thenceforward, and Forever Free is presented as part of Marquette University’s Freedom Project, a yearlong commemoration of the Sesquicentennial of the Civil War. The Project explores the many histories and meanings of emancipation and freedom in the United States and beyond. The exhibition features seven contemporary artists whose work deals with issues of race, gender, privilege, and identity, and more broadly conveys interpretations of the notion of freedom. Artists in Thenceforward are: Laylah Ali, Willie Birch, Michael Ray Charles, Gary Simmons, Elisabeth Subrin, Mark Wagner, and Kara Walker. Essayists for the exhibition catalogue are Dr. A. Kristen Foster, associate professor, Department of History, Marquette University, and Ms. Kali Murray, assistant professor, Marquette University Law School. Thenceforward, and Forever Free is sponsored in part by the Friends of the Haggerty, the Joan Pick Endowment Fund, the Marquette University Andrew W. Mellon Fund, a Marquette Excellence in Diversity Grant, the Martha and Ray Smith, Jr. Endowment Fund, the Nelson Goodman Endowment Fund, and the Wisconsin Arts Board with funds from the State of Wisconsin and the National Endowment for the Arts. 4 Art and the American Paradox A. Kristen Foster, Ph.D. Associate Professor Department of History Marquette University On December 1, 1862—before signing the Emancipation Proclamation, before the end of the Civil War, and before the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment—President Abraham Lincoln sent his Annual Message to Congress.