Toward a Class Analysis of the Indonesian Military Bureaucratic State*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of Thee Kian Wie's Major

Economics and Finance in Indonesia Vol. 61 No. 1, 2015 : 41-52 p-ISSN 0126-155X; e-ISSN 2442-9260 41 The Indonesian Economy from the Colonial Extraction Period until the Post-New Order Period: A Review of Thee Kian Wie’s Major Works Maria Monica Wihardjaa,∗, Siwage Dharma Negarab,∗∗ aWorld Bank Office Jakarta bIndonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) Abstract This paper reviews some major works of Thee Kian Wie, one of Indonesia’s most distinguished economic historians, that spans from the Colonial period until the post-New Order period. His works emphasize that economic history can guide future economic policy. Current problems in Indonesia were resulted from past policy failures. Indonesia needs to consistently embark on open economic policies, free itself from "colonial period mentality". Investment should be made in rebuilding crumbling infrastructure, improving the quality of health and education services, and addressing poor law enforcement. If current corruption persists, Indone- sia could not hope to become a dynamic and prosperous country. Keywords: Economic History; Colonial Period; Industrialization; Thee Kian Wie Abstrak Tulisan ini menelaah beberapakarya besar Thee Kian Wie, salah satu sejarawan ekonomi paling terhormat di Indonesia, mulai dari periode penjajahan hingga periode pasca-Orde Baru. Karya Beliau menekankan bahwa sejarah ekonomi dapat memberikan arahan dalam perumusan kebijakan ekonomi mendatang. Permasalahan yang dihadapi Indonesia dewasa ini merupakan akibat kegagalan kebijakan masa lalu. In- donesia perlu secara konsisten menerapkan kebijakan ekonomi terbuka, membebaskan diri dari "mentalitas periode penjajahan". Investasi perlu ditingkatkan untuk pembangunan kembali infrastruktur, peningkatan kualitas layanan kesehatan dan pendidikan, serta pembenahan penegakan hukum. Jika korupsi saat ini berlanjut, Indonesia tidak dapat berharap untuk menjadi negara yang dinamis dan sejahtera. -

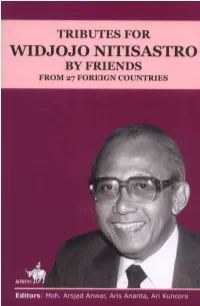

Tributes1.Pdf

Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Law No.19 of 2002 regarding Copyrights Article 2: 1. Copyrights constitute exclusively rights for Author or Copyrights Holder to publish or copy the Creation, which emerge automatically after a creation is published without abridge restrictions according the law which prevails here. Penalties Article 72: 2. Anyone intentionally and without any entitlement referred to Article 2 paragraph (1) or Article 49 paragraph (1) and paragraph (2) is subject to imprisonment of no shorter than 1 month and/or a fine minimal Rp 1.000.000,00 (one million rupiah), or imprisonment of no longer than 7 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 5.000.000.000,00 (five billion rupiah). 3. Anyone intentionally disseminating, displaying, distributing, or selling to the public a creation or a product resulted by a violation of the copyrights referred to under paragraph (1) is subject to imprisonment of no longer than 5 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 500.000.000,00 (five hundred million rupiah). Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Editors: Moh. Arsjad Anwar Aris Ananta Ari Kuncoro Kompas Book Publishing Jakarta, January 2007 Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Published by Kompas Book Pusblishing, Jakarta, January 2007 PT Kompas Media Nusantara Jalan Palmerah Selatan 26-28, Jakarta 10270 e-mail: [email protected] KMN 70007006 Editor: Moh. Arsjad Anwar, Aris Ananta, and Ari Kuncoro Copy editor: Gangsar Sambodo and Bagus Dharmawan Cover design by: Gangsar Sambodo and A.N. -

Gender, Equity and Development Edited by Kathryn Robinson And

The Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies (RSPAS) at The Australian National University (ANU) is home to the Indonesia Project, a major international centre of research and graduate training on the economy of Indonesia. Established in 1965 in the School’s Division of Economics, the Project is well known and respected in Indonesia and in other places where Indonesia attracts serious scholarly and official interest. Funded by ANU and the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID), the Project monitors and analyses recent economic developments in Indonesia; informs Australian governments, business and the wider community about those developments and about future prospects; stimulates research on the Indonesian economy; and publishes the respected Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies. The School’s Department of Political and Social Change (PSC) focuses on domestic politics, social processes and state–society relationships in Asia and the Pacific, and has a long-established interest in Indonesia. Together with PSC and RSPAS, the Project holds the annual Indonesia Update conference, whose proceedings are published in the Indonesia Assessment series. Each Update (and resulting Assessment volume) offers an overview of recent economic and political developments, and devotes attention to a significant theme in Indonesia’s development. The Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS) in Singapore was established as an autonomous organization in 1968. It is a regional research centre for scholars and other specialists concerned with modern Southeast Asia, particularly the many-faceted problems of stability and security, economic development, and political and social change. The Institute’s research programmes are the Regional Economic Studies (RES, including ASEAN and APEC), Regional Strategic and Political Studies (RSPS), and Regional Social and Cultural Studies (RSCS). -

Indonesia Assessment 1991

Indonesia Assessment 1991 Hal Hill, editor Political and Social Change Monograph 13 Political and Social Change Monograph 13 Indonesia Assessment 1991 Proceedings of Indonesia Update Conference, August 1991 Indonesia Project, Department of Economics and Department of Political and Social Change, Research School of Pacific Studies, ANU Hal Hill (ed.) Department of Political and Social Change Research School of Pacific Studies Australian National University Canberra, 1991 © Hal Hill and the several authors each in respect of the papers contributed by them; for the full list of the names of such copyright owners and the papers in respect of which they are the copyright owners see the Table of Contents of this volume. This work is copyright. Apart from any fair dealings for the purpose of study, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries may be made to the publisher. First published 1991, Department of Political and Social Change, Research School of Pacific Studies, The Australian National University. Printed and manufactured in Australia by Panther Publishing and Press. Distributed by Department of Political and Social Change Research School of Pacific Studies Australian National University GPO Box 4 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia (FAX: 06-257-1 893) National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-publication entry Indonesia Update Conference (1991 Australian National University). Indonesia Assessment, proceedings of Indonesia Update Conference, August 1991 Bibliography. Includes index ISBN 0 7315 1291 X 1. Education, Higher - Indonesia - Congresses. 2. Indonesia - Economic conditions - 1966- - Congresses. 3. Indonesia - Politics and government- 1%6- - Congresses. I. -

Table of Content

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Elites and economic policies in Indonesia and Nigeria, 1966-1998 Fuady, A.H. Publication date 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Fuady, A. H. (2012). Elites and economic policies in Indonesia and Nigeria, 1966-1998. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:29 Sep 2021 Chapter 6 Elites and Industrialization Policy Industrialization has been regarded as a major factor contributing to divergent economic development in Asia and Africa. This has also been a feature of Indonesia–Nigeria comparisons since the 1980s. Since the mid- 1980s, the manufacturing sector has been an engine of growth in Indonesia. Contribution of the sector to the country‟s GDP increased significantly, from 8 percent in 1965 to 29 percent in 2003 (World Bank, 2007b). -

Chinese Big Business in Indonesia Christian Chua

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarBank@NUS CHINESE BIG BUSINESS IN INDONESIA THE STATE OF CAPITAL CHRISTIAN CHUA NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2006 CHINESE BIG BUSINESS IN INDONESIA THE STATE OF CAPITAL CHRISTIAN CHUA (M.A., University of Göttingen/Germany) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2006 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Throughout the years working on this study, the list of those who ought to be mentioned here grew tremendously. Given the limited space, I apologise that these acknowledgements thus have to remain somewhat incomplete. I trust that those whose names should, but do not, ap- pear here know that I am aware of and grateful for the roles they played for me and for this thesis. However, a few persons cannot remain unstated. Most of all, I owe my deepest thanks to my supervisor Vedi Hadiz. Without him, I would not have begun work on this topic and in- deed, may have even given up along the way. His patience and knowledgeable guidance, as well as his sharp mind and motivation helped me through many crises and phases of despair. I am thankful, as well, for the advice and help of Mary Heidhues, Anthony Reid, Noorman Ab- dullah, and Kelvin Low, who provided invaluable feedback on early drafts. During my fieldwork in Indonesia, I was able to work as a Research Fellow at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Jakarta thanks to the kind support of its direc- tor, Hadi Soesastro. -

En Volkenkunde 144 (1988), No: 2/3, Leiden, 236-247 This PDF-File

A. Oki Economic studies In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 144 (1988), no: 2/3, Leiden, 236-247 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 12:50:59AM via free access AKIRA OKI ECONOMIC STUDIES Japan has often been criticized for showing an interest in Southeast Asia solely in terms of economie benefit, not of the culture or history of the region. In view of this sort of criticism, one might reasonably expect a plethora of economie studies of this region by Japanese scholars. So f ar as academie work is concerned, however, one will be surprised at the relative paucity of economie studies, both when one considers the close economie relations between the two countries and when one compares this with other fields of study, such as politics, history in general, and cultural and social studies. The same applies to Indónesia itself. There may be several reasons for this. Among other things, Japanese students of economics proper are not, generally speaking, especially interested in Southeast Asian countries like Indónesia. Differently from, for instance, Australia, where one finds a sizable group of economists specialized on Indónesia, in Japan such economists are scarce. Nevertheless, a large number of studies of the Indonesian economy must have been made by Japanese scholars in connection with Japanese economie aid and investments by Japanese companies. However, such reports and studies have rarely been published or publicized. Since it is almost impossible to tracé these economie studies, we will exclude them from the present survey. -

A National Mental Revolution

A NATIONAL MENTAL REVOLUTION THROUGH THE RESTORATION OF CITIES OF COLONIAL LEGACY: TOWARDS BUILDING A STRONG NATION’S CHARACTER An Urban Cultural Historical and Bio Psychosocial Overview By Martono Yuwono and Krishnahari S. Pribadi, MD *) “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us” --- (Sir Winston Churchill). “The young generation does not realize how hard and difficult it was when Indonesia struggled for our independence throughout three hundred years of colonization. They have to learn thoroughly from our history and to use the experiences and leadership of the older generations, as guidance and role models. They have to understand about our national identity. When they do not know their national’s identity, where would they go?” (Ali Sadikin’s statement as interviewed by Express Magazine, June 1, 1973, and several times discussions with Martono Yuwono) “Majapahit", a strong maritime nation in the 14th century The history of Indonesia as a maritime nation dates back to the 14th century when this South East Asian region was subjected under the reign of the great “Majapahit” Empire. The Empire ruled a region which is geographically located between two great continents namely Asia and Australia, and at the same time between two great oceans namely the Pacific and the Indian oceans. This region consisted of mainly the archipelagic group of islands (which is now referred to as Indonesia), and some portion of the coastal region at the south eastern tip of the Asian continent. “Majapahit” was already the largest archipelagic state in the world at that time, in control of the strategic cross roads (sea lanes) between those two great continents and two great oceans. -

Indonesian Technocracy in Transition: a Preliminary Analysis*

Indonesian Technocracy in Transition: A Preliminary Analysis* Shiraishi Takashi** Indonesia underwent enormous political and institutional changes in the wake of the 1997–98 economic crisis and the collapse of Soeharto’s authoritarian regime. Yet something curious happened under President Yudhoyono: a politics of economic growth has returned in post-crisis decentralized, democratic Indonesia. The politics of economic growth is politics that transforms political issues of redistribution into problems of output and attempts to neutralize social conflict in favor of a consensus on growth. Under Soeharto, this politics provided ideological legitimation to his authoritarian regime. The new politics of economic growth in post-Soeharto Indo- nesia works differently. Decentralized democracy created a new set of conditions for doing politics: social divisions along ethnic and religious lines are no longer suppressed but are contained locally. A new institutional framework was also cre- ated for the economic policy-making. The 1999 Central Bank Law guarantees the independence of the Bank Indonesia (BI) from the government. The Law on State Finance requires the government to keep the annual budget deficit below 3% of the GDP while also expanding the powers of the Ministry of Finance (MOF) at the expense of National Development Planning Agency. No longer insulated in a state of political demobilization as under Soeharto, Indonesian technocracy depends for its performance on who runs these institutions and the complex political processes that inform their decisions and operations. Keywords: Indonesia, technocrats, technocracy, decentralization, democratization, central bank, Ministry of Finance, National Development Planning Agency At a time when Indonesia is seen as a success story, with its economy growing at 5.9% on average in the post-global financial crisis years of 2009 to 2012 and performing better * I would like to thank Caroline Sy Hau for her insightful comments and suggestions for this article. -

F Re E P O Rt and the Suharto Regime, 1 965–1 9

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Fre e p o r t and the Suharto Regime, provided by ScholarSpace at University of Hawai'i at Manoa 19 65–19 9 8 Denise Leith In functioning democratic economies a structural balance must be found between state and capital. In Suharto’s autocratic state, however, a third variable upset this equation: patronage. By using access to resources and business as the major lubricant of his patronage style of leadership Suharto actively encouraged the involvement of all powerful groups within the ec o n o m y . Eventually, the military, politicians, and the bureaucracy became intimately involved in the most lucrative business ventures to the point that to be successful in Indonesian business one required an influential partner in at least one of these institutional groups, preferably with direct access to Suharto. When Freeport began negotiations with the new military regime in Jakarta in 1967 to mine the copper in West Papua, the American transna- tional with the valuable political connections was the more powerful of the negotiating parties, enabling it to dictate the terms of its contract. As Suharto’s political confidence grew and as the American company’s finan- cial investment in the province increased—and by association its vulner- ability—the balance of power shifted in Jakarta’s favor. Eventually Free- port became another lucrative source of patronage for the president. E a r ly Histo ry of Fr e e p o rt in West Pa p ua In 1936, while on an expedition to the center -

Culture of Abuse of Power Due to Conflict of Interest to Corruption for Too Long on the Management Form Resources of Oil and Gas in Indonesia

International Journal of Criminology and Sociology, 2020, 9, 247-254 247 Culture of Abuse of Power Due to Conflict of Interest to Corruption for Too Long on The Management form Resources of Oil and Gas in Indonesia Bambang Slamet Riyadi* Lecturer of Business Law and Criminology at the Faculty of Law, University of Nasional, Jakarta Indonesia Abstract: This research is a culture of abuse of power due to conflicts of interest so that corruption takes too long to manage oil and natural gas resources in Indonesia in managing oil and natural gas resources in Indonesia. The problem of this research is that the Indonesian state is equipped with abundant natural resources, including oil and natural gas resources. According to Article 33 of the 1945 Constitution, the oil and natural gas resources should be controlled by the state for the greatest prosperity of the people. In fact, the Indonesian people are not prosperous despite the abundance of oil and natural gas resources. Historical research methods. With the concept of cultural criminology. The results of research since the independence of the Republic of Indonesia have occurred abuse of power due to conflicts of interest to maintain power in the management of oil and gas with corruption impacting state losses, especially the suffering of the Indonesian people for too long, so that a culture of corruption is formed. This happens first; the sudden change component, caused by global changes and the modernization of the tendency of society to comply with materialism and consumerism while ignoring the cultural values of shame in the life of the nation and state. -

Bab Iv Penyajian Dan Analisis Data

BAB IV PENYAJIAN DAN ANALISIS DATA 4.1 Penyajian Data 4.1.1 Sejarah Perminyakan di Indonesia Perminyakan di Indonesia terbagi dalam tiga jaman yaitu masa penjajahan Hindia Belanda, masa pendudukan Jepang dan masa Indonesiamerdeka. Dari ketiga jaman tersebut untuk penjelasanya adalah sebagai berikut: 1. Jaman Penjajahan Hindia Belanda Sejarah perminyakan di Indonesia dimulai pada abad VIII dimana pada saat itu penduduk yang tinggal di sekitar Selat Sumatera telah menggunakan minyak bumi yang digunakan sebagai bahan bakar untuk pertempuran laut. Pada tahun 1871 pengeboran minyak bumi pertama kali di Indonesia dilakukan oleh Jan Roerink dan Yan Hoeyel di Gunung Cermai, Cirebon tapi mereka tidak mendapatkan hasil yang diharapkan. Kemudian pada tahun 1833, Aj Zijlker, seorang pengusaha perkebunan berkebangsaan Belanda, melakukan pengeboran minyak bumi di Telaga Tiga, Pangkalan Brandan dan hasil pengeboran minyak bumi ini tidak mempunyai nilai ekonomis. Dalam usahanya menemukan lahan minyak di Indonesia akhirnya pada tanggal 15 Juni 1885 Zijlker menemukan ladang minyak yang mempunyai nilai produksi komersial yaitu pada Sumur Telaga SaidSumatera Utara, oleh karena itu tanggal 15 Juni di tetapkan sebagai hari industri perminyakan Indonesia. 33 34 Pada tahun 1912 perusahaan Amerika “TANDARD” memasuki Hindia Belanda yang mempunyai daerah operasi (kekuasaan) didaerah lapangan Talang Akar Pendopo, Sumatera Selatan. BPM sebagai grup minyak Belanda dan Inggris melakukan kerjasama dengan pemerintah Hindia Belanda dengan pembagian saham 50:50 dalam perusahaan NIAM (Nederlandsche Aarbolie Maatcappij) yang mengusahakan minyak di Jambi, Pulau Bunyu, Kalimantan Timur pada tahun 1930 perusahaan Standard California membuka cabang di Hindia Belanda dengan nama NPPM (Nederlandsche Pasific Petroleum Mij) dan setelah Standard California bekerja sama dengan Texas Company maka NPPM dilebur menjadi milik kedua perusahaan dengan nama CALTEX (California Texas Company) yang mendapat konsensi didaerah sepanjang pantai Sumatera Tengah.