Vol. 5 2021 Beyond Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nomination Press Release

Elisabeth Moss as Peggy Olson Outstanding Lead Actor In A Drama Series Nashville • ABC • ABC Studios Connie Britton as Rayna James Breaking Bad • AMC • Sony Pictures Television Scandal • ABC • ABC Studios Bryan Cranston as Walter White Kerry Washington as Olivia Pope Downton Abbey • PBS • A Carnival / Masterpiece Co-Production Hugh Bonneville as Robert, Earl of Grantham Outstanding Lead Actor In A Homeland • Showtime • Showtime Presents, Miniseries Or A Movie Teakwood Lane Productions, Cherry Pie Behind The Candelabra • HBO • Jerry Productions, Keshet, Fox 21 Weintraub Productions in association with Damian Lewis as Nicholas Brody HBO Films House Of Cards • Netflix • Michael Douglas as Liberace Donen/Fincher/Roth and Trigger Street Behind The Candelabra • HBO • Jerry Productions, Inc. in association with Media Weintraub Productions in association with Rights Capital for Netflix HBO Films Kevin Spacey as Francis Underwood Matt Damon as Scott Thorson Mad Men • AMC • Lionsgate Television The Girl • HBO • Warner Bros. Jon Hamm as Don Draper Entertainment, GmbH/Moonlighting and BBC in association with HBO Films and Wall to The Newsroom • HBO • HBO Entertainment Wall Media Jeff Daniels as Will McAvoy Toby Jones as Alfred Hitchcock Parade's End • HBO • A Mammoth Screen Production, Trademark Films, BBC Outstanding Lead Actress In A Worldwide and Lookout Point in association Drama Series with HBO Miniseries and the BBC Benedict Cumberbatch as Christopher Tietjens Bates Motel • A&E • Universal Television, Carlton Cuse Productions and Kerry Ehrin -

THE DOCUMENTARY IMAGINATION an Investigation by Video Practice Into the Performative Application of Documentary Film in Scholarship

THE DOCUMENTARY IMAGINATION An investigation by video practice into the performative application of documentary film in scholarship Trevor William Hearing A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 Bournemouth University This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. II ABSTRACT THE DOCUMENTARY IMAGINATION An investigation by video practice into the performative application of documentary film in scholarship The aim of the research has been to discover new ways in which documentary film might be developed as a performative academic research tool. In reviewing the literature I have acknowledged the well-established use of observational documentary film making in ethnography and visual anthropology underpinned by a positivist epistemology, but I suggest there are forms of reportage in literary and dramatic traditions as well as film that are more relevant to the possibility of an auto-ethnographic approach which applies documentary film in an evocative context. I have examined the newly emerging field of Performative Social Science and the "new subjectivity" evident in documentary film to investigate emerging opportunities to research and disseminate scholarly knowledge employing reflective documentary film methods in place of, or alongside, text. This inquiry has prompted me to consider the history of the creation and transmission of scholarship. The research methodology I have employed has been auto- ethnographic reflective film practice. -

Hamptons Doc Fest 2020 Congratulations on 13 Years of Championing Documentary Films!

Art: Nofa Aji Zatmiko ALL DOCS ALL DAY DOCS ALL ALL OPENING NIGHT FILM: MLK/FBI Hamptons Doc Fest DECEMBER 4–13, 2020 www.hamptonsdocfest.com is a year we will long Wiseman and his newest film, City Hall. 2020 rememberWELCOME or want LETTER to He stands as one of the documentary forget. Deprived of a movie theater’s giants that every aspiring filmmaker magic we struggled to take the virtual learns from, that Wiseman way of plunge. Ultimately, we decided on yes observing life unfold. Our Award films we can to bring you our 13th festival capture the essence of Art & Music, in these overwhelming times. We Human Rights, and the Environment. programmed 35 great documentary Our Opening night film reveals a hidden films to watch in the warmth and chapter in Martin Luther King’s world. comfort of your home over 10 days. No New this year, you’ll hear and see UP worries about weather, parking, ticket CLOSE video clips presented by the lines, where to catch a snack between Directors of each film. My thanks to an films. You can schedule your own day extraordinary team, and to our Artistic the way you like it. Consider it not Director, Karen Arikian. Lastly, you will only a festival experience but a virtual find all the information and help you’ll festival experiment. need to watch films on your television, When Covid hit, Hamptons Doc Fest tablet or computer. So click on and went into overdrive. We were forced step into the big virtual world wherever to cancel our Docs Equinox Spring you are. -

Mutual Watching and Resistance to Mass Surveillance After Snowden

Media and Communication (ISSN: 2183-2439) 2015, Volume 3, Issue 3, Pages 12-25 Doi: 10.17645/mac.v3i3.277 Article “Veillant Panoptic Assemblage”: Mutual Watching and Resistance to Mass Surveillance after Snowden Vian Bakir School of Creative Studies and Media, Bangor University, Bangor, LL57 2DG, UK; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 9 April 2015 | In Revised Form: 16 July 2015 | Accepted: 4 August 2015 | Published: 20 October 2015 Abstract The Snowden leaks indicate the extent, nature, and means of contemporary mass digital surveillance of citizens by their intelligence agencies and the role of public oversight mechanisms in holding intelligence agencies to account. As such, they form a rich case study on the interactions of “veillance” (mutual watching) involving citizens, journalists, intelli- gence agencies and corporations. While Surveillance Studies, Intelligence Studies and Journalism Studies have little to say on surveillance of citizens’ data by intelligence agencies (and complicit surveillant corporations), they offer insights into the role of citizens and the press in holding power, and specifically the political-intelligence elite, to account. Atten- tion to such public oversight mechanisms facilitates critical interrogation of issues of surveillant power, resistance and intelligence accountability. It directs attention to the veillant panoptic assemblage (an arrangement of profoundly une- qual mutual watching, where citizens’ watching of self and others is, through corporate channels of data flow, fed back into state surveillance of citizens). Finally, it enables evaluation of post-Snowden steps taken towards achieving an equiveillant panoptic assemblage (where, alongside state and corporate surveillance of citizens, the intelligence-power elite, to ensure its accountability, faces robust scrutiny and action from wider civil society). -

Tisch School of the Arts

18 Visible TISCH SCHOOL New York University EOFvidence THE ARTS August 11-14, 2011 NEW YORK, WELCOME EVER VIGILANT, IS THE CITY THAT never sleeps, a perfect setting for an international TO YOU ALL! conference on documentary film. We extend our thanks to Tisch School of the Arts, Cinema Studies Pro- WITHIN THE BROADER CONTEXT fessor, and Visible Evidence 18 Conference Director, Jon- of our Moving Image Archiving and Preservation Program athan Kahana for his energetic efforts to bring the confer- and Certificate Program in Culture and Media, the De- ence to the Big Apple. Professor Kahana has deployed his superb organizational skills to assemble an impressive set of partment of Cinema Studies at NYU is committed to sponsoring institutions and panelists over the four days of the developing both pedagogy and practice in the field conference and we are grateful to him and the legion of vol- of documentary. The fact that this year we are unteers and participating institutions who made hosting Visible Evidence 18 is a demonstra- this event possible. The Visible Evidence 18 Con- ference is a bittersweet occasion: we celebrate a tion of that commitment as well as a validation, great filmmaker, the “dean” of documentary film, as Jonathan Kahana writes, of documentary film-mak- George Stoney, Professor Emeritus in the Tisch ers’ long love affair with New York. I want to congratulate School’s Kanbar Institute of Film and Television, Professor Kahana for putting together this stellar conference and we pay tribute to our school’s beloved and renowned theorist and historian, the late Rob- and mobilizing such a wide range of institutional collabora- ert Sklar, Professor Emeritus in the department tors across the city. -

Thi Bui's the Best We Could Do: a Teaching Guide

Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do: A Teaching Guide The UO Common Reading Program, organized by the Division of Undergraduate Studies, builds community, enriches curriculum, and engages research through the shared reading of an important book. About the 2018-2019 Book A bestselling National Book Critics Circle Finalist, Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do offers an evocative memoir about the search for a better future by seeking to understand the past. The book is a marvelous visual narrative that documents the story of the Bui family escape after the fall of South Vietnam in the 1970s, and the difficulties they faced building new lives for themselves as refugees in America. Both personal and universal, the book explores questions of community and family, home and healing, identity and heritage through themes ranging from the refugee experience to parenting and generational changes. About the Author Thi Bui is an author, illustrator, artist, and educator. Bui was born in Vietnam three months before the end of the Vietnam War and came to the United States in 1978 as part of a wave of refugees from Southeast Asia. Bui taught high school in New York City and was a founding teacher of Oakland International High School, the first public high school in California for recent immigrants and English learners. She has taught in the MFA in Comics program at California College for the Arts since 2015. The Best We Could Do (Abrams ComicArts, 2017) is her debut graphic novel. She is currently researching a work of graphic nonfiction about climate change in Vietnam. -

AT&T-Time Warner Merger Overview

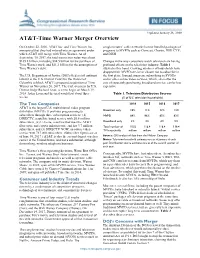

Updated January 26, 2018 AT&T-Time Warner Merger Overview On October 22, 2016, AT&T Inc. and Time Warner Inc. conglomerates’ cable networks license bundled packages of announced that they had entered into an agreement under programs to MVPDs such as Comcast, Charter, DIRECTV, which AT&T will merge with Time Warner. As of and DISH. September 30, 2017, the total transaction value was about $105.8 billion, including $84.5 billion for the purchase of Changes in the way consumers watch television are having Time Warner stock, and $21.3 billion for the assumption of profound effects on the television industry. Table 1 Time Warner’s debt. illustrates this trend. Growing numbers of households have dropped their MVPD service or chosen not to subscribe in The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) filed a civil antitrust the first place. Instead, many are subscribing to SVODs lawsuit in the U.S. District Court for the District of and/or other online video services, which, even after the Columbia to block AT&T’s proposed acquisition of Time cost of separately purchasing broadband service, can be less Warner on November 20, 2017. The trial, overseen by U.S. expensive. District Judge Richard Leon, is set to begin on March 19, 2018. Judge Leon said the trial would last about three Table 1. Television Distribution Sources weeks. (% of U.S. television households) The Two Companies 2014 2015 2016 2017 AT&T is the largest U.S. multichannel video program distributor (MVPD). It provides programming to Broadcast only 10% 11% 12% 13% subscribers through three subscription services: (1) MVPD 88% 86% 85% 82% DIRECTV, a satellite-based service with 20.6 million subscribers, (2) U-Verse, a service that uses the AT&T Broadband only 2% 3% 4% 5% fiber optic and copper infrastructure and has 3.7 million Total number of 115.5 116.4 116.4 118.4 subscribers, and (3) DIRECTV NOW, an online video TV households million million million million service with 787,000 subscribers. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Directing For A Documentary/Nonfiction Program Adam Ruins Everything Adam Ruins Guns November 27, 2018 Adam Conover takes aim at both sides of the gun debate by explaining why an assault weapons ban would be ineffective at stopping gun violence, outlining how the Second Amendment has been twisted to benefit the NRA, and revealing that liberal and conservative gun policies have impacted people of color. Tim Wilkime, Directed by America To Me Listen To The Poem! September 30, 2018 Spring semester brings fresh challenges. Jada clashes with junior Diane over her new film. Brendan recalls a racially charged basketball past. Tiara and the cheerleading squad go for the gold. Charles’ poetry slam team faces an epic challenge. Steve James, Directed by American Dream/American Knightmare December 21, 2018 Documentary that delves into the life and exploits of the iconic Death Row Records co-founder Suge Knight, and the era in gangsta rap he presided over. Through a series of face-to-face interviewers, Knight reveals exactly how it all happened and why it all fell apart. Antoine Fuqua, Directed by American Experience: The Circus October 08, 2018 - October 09, 2018 American Experience: The Circus explores the colorful history of this popular, influential and distinctly American form of entertainment, from the first one-ring show at the end of the 18th century to 1956, when the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey big top was pulled down for the last time. Sharon Grimberg, Directed by American Experience: The Eugenics Crusade October 16, 2018 American Experience: The Eugenics Crusade explores the unknown campaign to breed a “better” American race. -

Julia Reichert and the Work of Telling Working-Class Stories

FEATURES JULIA REICHERT AND THE WORK OF TELLING WORKING-CLASS STORIES Patricia Aufderheide It was the Year of Julia: in 2019 documentarian Julia Reichert received lifetime-achievement awards at the Full Frame and HotDocs festivals, was given the inaugural “Empowering Truth” award from Kartemquin Films, and saw a retrospec- tive of her work presented at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. (The International Documentary Association had already given her its 2018 award.) Meanwhile, her newest work, American Factory (2019)—made, as have been all her films in the last two decades, with Steven Bognar—is being championed for an Academy Award nomination, which would be Reichert’s fourth, and has been picked up by the Obamas’ new Higher Ground company. A lifelong socialist- feminist and self-styled “humanist Marxist” who pioneered independent social-issue films featuring women, Reichert was also in 2019 finishing another film, tentatively titled 9to5: The Story of a Movement, about the history of the movement for working women’srights. Yet Julia Reichert is an underrecognized figure in the contemporary documentary landscape. All of Reichert’s films are rooted in Dayton, Ohio. Though periodically rec- ognized by the bicoastal documentary film world, she has never been a part of it, much like her Chicago-based fellow Julia Reichert in 2019. Photo by Eryn Montgomery midwesterners: Kartemquin Films (Gordon Quinn, Steve James, Maria Finitzo, Bill Siegel, and others) and Yvonne 2 The Documentary Film Book. She is absent entirely from Welbon. 3 Gary Crowdus’s A Political Companion to American Film. Nor has her work been a focus of very much documentary While her earliest films are mentioned in many texts as scholarship. -

Ftc-2018-0091-D-0015-163436.Pdf

December 28, 2018 The Honorable Joseph Simons Chairman Federal Trade Commission 600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20580 Dear Chairman Simons, Thank you for inviting public comment on the question of whether U.S. antitrust agencies should publish new vertical merger guidelines, and how those guidelines should address competitive harms, transaction-related efficiencies, and behavioral remedies. We submit these comments on behalf of the Writers Guild of America West (“WGAW”), a labor organization representing more than 10,000 professional writers of motion pictures, television, radio, and Internet programming, including news and documentaries. Our members and the members of our affiliate, Writers Guild of America East (jointly, “WGA”) create nearly all of the scripted entertainment viewed in theaters and on television today as well as most of the original scripted series now offered by online video distributors (“OVDs”) such as Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, Crackle, and more. The Non-Horizontal Merger Guidelines (“Guidelines”), originally issued in 1984,1 are the governing document of U.S. vertical antitrust enforcement. They rely, however, upon outdated economic theories that not only fail to promote and protect competition, but, in some cases, obstruct appropriate antitrust enforcement. Large vertical mergers in key industries have caused harm to consumers and failed to deliver on their promised innovations, efficiencies, and public benefits. The current Guidelines’ bias toward false negatives, or non-findings of harm, enables incumbents to consolidate market power and undermine competition. Recent vertical mergers in the telecommunications and entertainment industries illustrate the deficiencies of the current regulatory regime and provide evidence of the need for new guidelines. -

The BG News February 13, 1987

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 2-13-1987 The BG News February 13, 1987 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News February 13, 1987" (1987). BG News (Student Newspaper). 4620. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/4620 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Spirits and superstitions in Friday Magazine THE BG NEWS Vol. 69 Issue 80 Bowling Green, Ohio Friday, February 13,1987 Death Funding cut ruled for 1987-88 Increase in fees anticipated suicide by Mike Amburgey said. staff reporter Dalton said the proposed bud- get calls for $992 million Man kills wife, The Ohio Board of Regents statewide in educational subsi- has reduced the University's dies for 1987-88, the same friend first instructional subsidy allocation amount funded for this year. A for 1987-88 by $1.9 million, and 4.7 percent increase is called for by Don Lee unless alterations are made in in the academic year 1988-89 Governor Celeste's proposed DALTON SAID given infla- wire editor budget, University students tionary factors, the governor's could face at least a 25 percent budget puts state universities in The manager of the Bowling instructional fee increase, a difficult place. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D.