Nuclear Weapons: the Reliable Replacement Warhead Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Organized Hypocrisy and International Organization Michael Lipson Department of Political Science

Dilemmas of Global Governance: Organized Hypocrisy and International Organization Michael Lipson Department of Political Science Concordia University 1455 de Maisonneuve Blvd. W. Montreal, QC H3G 1M8 Tel. (514) 8484-2424, ext. 2129 Fax (514) 848-4072 e-mail: [email protected] DRAFT: Please do not quote or cite without permission Comments welcome. Paper prepared for presentation at the annual meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association, Toronto, Ontario, June 1-3, 2006. Dilemmas of Global Governance: Organized Hypocrisy and International Organizations Critics of international organizations on the political left and right frequently accuse international institutions of hypocrisy. Yet the academic literature on international organizations lacks an explicit theory of the sources of inconsistencies on the part of international institutions. This paper argues that hypocrisy on the part of international organizations is an inevitable consequence of contradictory pressures in their organizational environments. Drawing on neo-institutionalist organizational sociology and work on “organized hypocrisy” applied to other settings, the paper presents a typology and framework for analyzing the bases and consequences – both positive and negative – of different forms of hypocrisy in global governance and formal international organizations. The argument is illustrated with reference to organizational hypocrisy on the part of the United Nations and the nuclear nonproliferation regime. Dilemmas of Global Governance Introduction In the -

Heater Element Specifications Bulletin Number 592

Technical Data Heater Element Specifications Bulletin Number 592 Topic Page Description 2 Heater Element Selection Procedure 2 Index to Heater Element Selection Tables 5 Heater Element Selection Tables 6 Additional Resources These documents contain additional information concerning related products from Rockwell Automation. Resource Description Industrial Automation Wiring and Grounding Guidelines, publication 1770-4.1 Provides general guidelines for installing a Rockwell Automation industrial system. Product Certifications website, http://www.ab.com Provides declarations of conformity, certificates, and other certification details. You can view or download publications at http://www.rockwellautomation.com/literature/. To order paper copies of technical documentation, contact your local Allen-Bradley distributor or Rockwell Automation sales representative. For Application on Bulletin 100/500/609/1200 Line Starters Heater Element Specifications Eutectic Alloy Overload Relay Heater Elements Type J — CLASS 10 Type P — CLASS 20 (Bul. 600 ONLY) Type W — CLASS 20 Type WL — CLASS 30 Note: Heater Element Type W/WL does not currently meet the material Type W Heater Elements restrictions related to EU ROHS Description The following is for motors rated for Continuous Duty: For motors with marked service factor of not less than 1.15, or Overload Relay Class Designation motors with a marked temperature rise not over +40 °C United States Industry Standards (NEMA ICS 2 Part 4) designate an (+104 °F), apply application rules 1 through 3. Apply application overload relay by a class number indicating the maximum time in rules 2 and 3 when the temperature difference does not exceed seconds at which it will trip when carrying a current equal to 600 +10 °C (+18 °F). -

Influencer Poll: Likelihood to Recommend & Support

Wave 56 Influencer Poll Update January 2018 Public Release Influencer Poll: Likelihood to Recommend & Support 1 Likelihood to Recommend and Support Military Service Likelihood to Recommend and Support Military Service 80% 71% 70% 71% 70% 66% 66% 66% 67% 63% 63% 63% 64% 61% 63% 60% 50% 46% 47% 47% 45% 44% 42% 43% 42% 39% 38% 40% 35% 32% 33% 34% 34% 30% 20% 10% Likely to Recommend: % Likely/Very Likely Likely to Support: % Agree/Strongly Agree Yearly Quarterly 0% Jan–Mar 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Likely to Recommend Military Service Likely to Support Decision to Join § Influencers’ likelihood to support the decision to join the Military increased significantly from 67% in 2015 to 70% in 2016. § However, Influencers’ likelihood to support the decision to join the Military remained stable in January–March 2017. = Significantly change from previous poll Source: Military Ad Tracking Study (Influencer Market) Wave 56 2 Questions: q1a–c: “Suppose [relation] came to you for advice about various post-high school options. How likely is it that you would recommend joining a Military Service such as the Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, or Coast Guard?” q2ff: “If [relation] told me they were planning to join the Military, I would support their decision.” Likelihood to Recommend Military Service By Influencer Type Likelihood to Recommend Military Service 80% 70% 63% 59% 59% 60% 58% 60% 57% 56% 57% 55% 54% 53% 48% 55% 50% 54% 47% 52% 51% 44% 51% 47% 42% 42% 42% 49% 41% 43% 42% 45% 45% 46% 40% 42% 37% 41% 39% 41% 38% 38% 38% 37% 37% 39% 34% 35% 34% 30% 33% 33% 32% 33% 32% 31% 32% 31% 31% 31% 32% 20% 25% 25% 24% 31% 29% 10% % Likely/Very Likely Yearly Quarterly 0% Jan–Mar 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 Fathers Mothers Grandparents Other Influencers § Influencers’ likelihood to recommend military service remained stable in January–March 2017 for all influencer groups. -

Case I,I,Emptyset,P7.Nb

Definitions: In[56]:= $Assumptions = w12 ≥ 0 && w13 ≥ 0 && w16 ≥ 0 && w24 ≥ 0 && w25 ≥ 0 && w36 ≥ 0 && w45 ≥ 0 && u > 0 && v > 0 && w21 ≥ 0 && w31 ≥ 0 && w61 ≥ 0 && w42 ≥ 0 && w52 ≥ 0 && w63 ≥ 0 && w54 ≥ 0 && K34 > 0 && K56 > 0 && K31 > 0 && K51 > 0 w = {{0, w12, w13, 0, 0, w16}, {w21, 0, 0, w24, w25, 0}, {w31, 0, 0, u, 0, w36}, {0, w42, u / K34, 0, w45, 0}, {0, w52, 0, w54, 0, v}, {w61, 0, w63, 0, v / K56, 0}} Out[56]= w12 ≥ 0 && w13 ≥ 0 && w16 ≥ 0 && w24 ≥ 0 && w25 ≥ 0 && w36 ≥ 0 && w45 ≥ 0 && u > 0 && v > 0 && w21 ≥ 0 && w31 ≥ 0 && w61 ≥ 0 && w42 ≥ 0 && w52 ≥ 0 && w63 ≥ 0 && w54 ≥ 0 && K34 > 0 && K56 > 0 && K31 > 0 && K51 > 0 Out[57]= {0, w12, w13, 0, 0, w16}, {w21, 0, 0, w24, w25, 0}, {w31, 0, 0, u, 0, w36}, u v 0, w42, , 0, w45, 0, {0, w52, 0, w54, 0, v}, w61, 0, w63, 0, , 0 K34 K56 In[58]:= MatrixForm[w] Out[58]//MatrixForm= 0 w12 w13 0 0 w16 w21 0 0 w24 w25 0 w31 0 0 u 0 w36 0 w42 u 0 w45 0 K34 0 w52 0 w54 0 v w61 0 w63 0 v 0 K56 Sum of rows In[59]:= d = Table[Total[w[[i, All]]], {i, 6}] d34 = Collect[Expand[d[[3]] * d[[4]] - w[[3, 4]] * w[[4, 3]]], u] d56 = Collect[Expand[d[[5]] * d[[6]] - w[[5, 6]] * w[[6, 5]]], v] u v Out[59]= w12 + w13 + w16, w21 + w24 + w25, u + w31 + w36, + w42 + w45, v + w52 + w54, + w61 + w63 K34 K56 w31 w36 Out[60]= w31 w42 + w36 w42 + w31 w45 + w36 w45 + u + + w42 + w45 K34 K34 w52 w54 Out[61]= w52 w61 + w54 w61 + w52 w63 + w54 w63 + v + + w61 + w63 K56 K56 Effective reaction rates after elimination of metabolites 5 and 6 (useful for easy differentiation w.r.to u), and the final effective reaction rate -

Improving Health Through Evidence-Based Probiotics

Improving health through evidence-based probiotics Company Profile & Probiotic Portfolio wincloveprobiotics.com vw Company Profile Winclove Probiotics Developing probiotic formulations since 1991 with a strong emphasis on research Winclove Probiotics, established in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, has been specializing in research, development and manufacturing of probiotic formulations for over 25 years. Our probiotic formulations are developed in close collaboration with leading research institutes, universities and academic hospitals. This enables us to develop innovative multispecies probiotic formulations for many different health indications. We continuously invest in research and technologies in order to develop the most effective probiotics that ensure end-users with the best solution. Looking for business opportunities? Winclove’s mission is to create long-lasting, sustainable and strategic partnerships. To achieve this, we offer innovative, high-quality and competitive probiotic solutions, as well as in-house scientific expertise and sales support. Our indication-specific formulations are designed for specific microbiota-related indications. The thorough substantiation of our probiotic formulations with scien- tific and clinical evidence makes them ideal for selling medically endorsed. We are a committed business partner and are looking forward to starting a fruitful collaboration with you! Product package Dossiers Technical lab analysis, in vitro data, etc. Clinical in vivo studies, Development of Probiotic blend post market studies, -

Nuclear Weapons: the Reliable Replacement Warhead Program

Order Code RL32929 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Nuclear Weapons: The Reliable Replacement Warhead Program May 24, 2005 Jonathan Medalia Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Nuclear Weapons: The Reliable Replacement Warhead Program Summary Most current U.S. nuclear warheads were built in the 1980s, and are being retained longer than was planned. Yet warheads deteriorate with age, and must be maintained. The current approach monitors them for signs of aging. When problems are found, a Life Extension Program (LEP) rebuilds components. While some can be made to new specifications, a nuclear test moratorium bars that approach for critical components that would require a nuclear test. Instead, LEP rebuilds them as closely as possible to original specifications. Using this approach, the Secretaries of Defense and Energy have certified stockpile safety and reliability for the past nine years without nuclear testing. In the FY2005 Consolidated Appropriations Act, Congress initiated the Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW) program by providing $9 million for it. The program will study developing replacement components for existing weapons, trading off features important in the Cold War, such as high yield and low weight, to gain features more valuable now, such as lower cost, elimination of some hazardous materials, greater ease of manufacture, greater ease of certification without nuclear testing, and increased long-term confidence in the stockpile. It would modify components to make these improvements; in contrast, LEP makes changes mainly to maintain existing weapons. Representative David Hobson, RRW’s prime sponsor, views it as part of a comprehensive plan for the U.S. -

Nuclear Weapons Databook, Volume I 3 Stockpile

3 Stockpile Chapter Three USNuclear Stockpile This section describes the 24 types of warheads cur- enriched uranium (oralloy) as its nuclear fissile material rently in the U.S. nuclear stockpile. As of 1983, the total and is considered volatile and unsafe. As a result, its number of warheads was an estimated 26,000. They are nuclear materials and fuzes are kept separately from the made in a wide variety of configurations with over 50 artillery projectile. The W33 can be used in two differ- different modifications and yields. The smallest war- ent yield configurations and requires the assembly and head is the man-portable nuclear land mine, known as insertion of distinct "pits" (nuclear materials cores) with the "Special Atomic Demolition Munition" (SADM). the amount of materials determining a "low" or '4high'' The SADM weighs only 58.5 pounds and has an explo- yield. sive yield (W54) equivalent to as little as 10 tons of TNT, In contrast, the newest of the nuclear warheads is the The largest yield is found in the 165 ton TITAN I1 mis- W80,5 a thermonuclear warhead built for the long-range sile, which carries a four ton nuclear warhead (W53) Air-Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM) and first deployed equal in explosive capability to 9 million tons of TNT, in late 1981. The W80 warhead has a yield equivalent to The nuclear weapons stockpile officially includes 200 kilotons of TNT (more than 20 times greater than the only those nuclear missile reentry vehicles, bombs, artil- W33), weighs about the same as the W33, utilizes the lery projectiles, and atomic demolition munitions that same material (oralloy), and, through improvements in are in "active service."l Active service means those electronics such as fuzing and miniaturization, repre- which are in the custody of the Department of Defense sents close to the limits of technology in building a high and considered "war reserve weapons." Excluded are yield, safe, small warhead. -

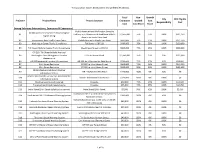

Draft Project List 2017-04-24

Transportation System Development Charge (TSDC) Project List Total Non- Growth City SDC Eligible Project # Project Name Project Location Estimated Growth Cost Responsibility Cost Cost Cost Share Share Driving Solutions (Intersections, Extensions & Expansions) Molalla Avenue from Washington Street to Molalla Avenue/ Beavercreek Road Adaptive D1 Gaffney Lane; Beavercreek Road from Molalla $1,565,000 75% 25% 100% $391,250 Signal Timing Avenue to Maple Lane Road D2 Beavercreek Road Traffic Surveillance Molalla Avenue to Maple Lane Road $605,000 75% 25% 100% $151,250 D3 Washington Street Traffic Surveillance 7th Street to OR 213 $480,000 75% 25% 100% $120,000 D4 7th Street/Molalla Avenue Traffic Surveillance Washington Street to OR 213 $800,000 75% 25% 100% $200,000 OR 213/ 7th Street-Molalla Avenue/ D5 Washington Street Integrated Corridor I-205 to Henrici Road $1,760,000 75% 25% 30% $132,000 Management D6 OR 99E Integrated Corridor Management OR 224 (in Milwaukie) to 10th Street $720,000 75% 25% 30% $54,000 D7 14th Street Restriping OR 99E to John Adams Street $845,000 74% 26% 100% $216,536 D8 15th Street Restriping OR 99E to John Adams Street $960,000 80% 20% 100% $192,000 OR 213/Beavercreek Road Weather D9 OR 213/Beavercreek Road $120,000 100% 0% 30% $0 Information Station Warner Milne Road/Linn Avenue Road Weather D10 Warner Milne Road/Linn Avenue $120,000 100% 0% 100% $0 Information Station D11 Optimize existing traffic signals Citywide $50,000 75% 25% 100% $12,500 D12 Protected/permitted signal phasing Citywide $65,000 75% 25% 100% -

High School Championship -- Standings

2017 TCA South Texas State Scholastic Championships: High School Championship -- Standings # Place Name ID Rtng Post Team Rd 1 Rd 2 Rd 3 Rd 4 Rd 5 Rd 6 Rd 7 Tot TBrk[M] TBrk[M] TBrk[S] TBrk[R] TBrk[C] 1 1 Priya Niki Trakru 13806686 2013 2033 STSTMAW63 W53 W18 W25 W12 W2 W6 7.0 30.5 24.5 34.5 34 28 2 2-5 Camille Y Kao 14297024 1969 1968 W85 W82 W32 W20 W11 L1 W15 6.0 29 22 32 25.5 26 3 Polo Stein 14275794 1709 1726 SBSBHSW69 W58 D10 W14 W27 D6 W16 6.0 28 22.5 31.5 27.25 24.5 4 Genta Kaieda 14354622 1888 1877 SHSHS W52 W41 L39 W43 W25 W22 W17 6.0 26.5 21.5 30.5 26.5 23 5 Fabian Olivares 13958918 1614 1656 SBSBHSW78 W16 W54 L39 W41 W11 W13 6.0 26.5 21.5 30 26.5 24 6 6-9 Jonathan Huerta 14086076 1748 1757 BRHHECHSW87 W111 W49 W26 W39 D3 L1 5.5 28.5 21.5 30.5 21 26 7 Satya G Holla 14354691 1698 1704 STSATSW72 W91 W33 L11 W26 W20 D8 5.5 27.5 22 30.5 23.25 23.5 8 Ritik Verma 13745958 1927 1903 CCVETERAW126 L44 W73 W30 W10 W36 D7 5.5 27 21.5 28.5 22.25 21.5 9 Jesus Guillen Jr 13762512 1791 1766 BRHHECHSW73 W108 L26 W111 D31 W40 W29 5.5 23.5 19 25.5 19.25 21.5 10 10-24 Nicholas Galindo 14494914 1390 1530 BRPORTERW99 W67 D3 W29 L8 W31 D12 5.0 29 23 32 21 22 11 Glen Ernest Rocha 16122046 1459 1543 HREARLYW65 W56 W84 W7 L2 L5 W44 5.0 29 23 32 20 23 12 Jorge Hernandez 14281624 1611 1617 SHSHS W51 W68 W44 W40 L1 D19 D10 5.0 29 22 32.5 20.5 23.5 13 Michael D Thomas 14793323 1783 1750 SBVMA W75 L43 W87 W42 W32 W28 L5 5.0 26.5 20.5 29.5 19.5 21 14 Jose Castillo Jr 14085711 1493 1504 BRHHECHSD103 W64 W35 L3 D30 W43 W40 5.0 26.5 20.5 29 19.5 19 15 Luis Ferna -

F. Bertinelli, Presentation 01-Sep-06

TCC, 1 September 2006 AT-CRI Progress and Outlook for Interconnections F. Bertinelli / AT-CRI (10 minutes) (on behalf of IC Team) • recent “news” since MARIC 2nd August • restart sector 4-5 • sector 7-8 1 SomeSome recentrecent newsnews…… AT-CRI Organisational: • internal AT reorganisation, IC project consolidation • already reinforcement of QA (D. Tommasini/MAS, R. Lopez/CRI) • F523: 4th full team contractually implemented, effective starting week 39/06 • Workflow: developed detailed workflow of activities, including: • pre-inspection and reflectometry • VAC and MEL tests (with recently introduced extended tests MPAQ and MHVQN) • ACR instrumentation • Planning: developed detailed planning, by activities, slots and weeks, extending to closure of W bellows and sector VAC testing TCC – September 2006 – F. Bertinelli 2 RestartRestart sectorsector 44--55 AT-CRI • IC work restarted this week 35/06 • IC work now in 4-5, continuing to 3-4 • detailed planning set up (activities, slots, weeks) for 4-5; 3-4 will follow • 2 full teams (at the moment BR, US, TIG: V, E, X, C’) • until week 39/06 will work Monday to Thursday, then extend to Saturday • 3rd large team starting week 39 • “forfait” (“lump sum”) invoicing • expected average productivity: 8 activities / week-team (but prepare work up to 10 - 12) • first partial results from week 35/06: • V1/V2 & E: 19 •BR: 16 •US: 11 • X: 12, C’: 21 TCC – September 2006 – F. Bertinelli 3 WorkflowWorkflow ICIC AT-CRI from P. Fessia TCC – September 2006 – F. Bertinelli 4 SectorSector 44--5:5: detaileddetailed planningplanning AT-CRI Planning sector 4-5 version 0.2 P. -

27Th Annual MLK Results

27TH ANNUAL MLK DAY TOURNAMENT RESULTS Page 1 of 12 LOWER PRIMARY SECTION 27TH ANNUAL MARTIN LUTHER KING DAY TOURNAMENT -- Lower Primary Standings, Page 1 Place Name/Team Rate Score MMed Solk Cum CumOp 1 Fei Alex (2,HICKORY GROVE ELEMENTARY, DUNLAP) 724 5.0 14.5 15.5 15.0 47.5 2 Tang, Bruce R (3,NGS) 702 5.0 13.5 15.5 15.0 51.5 3 Saravanan Pugazhendhi (1,BENJAMIN ELEMENTARY, BLOOMINGTON)806 4.0 15.0 17.0 14.0 54.0 4 Matejka Cole (7,THOMAS METCALF, NORMAL) 515 4.0 13.5 15.5 12.0 50.0 5 Thome Addy (6,THOMAS METCALF, NORMAL) 529 4.0 13.0 14.5 13.0 47.0 For Unrated 1 Ziegler Samuel (68,EPIPHANY, NORMAL) nnnn 3.5 13.5 16.0 11.0 45.0 2 Hafeez Ismail (47,COLENE HOOSE, NORMAL) nnnn 3.0 12.0 13.0 9.0 40.0 For Ratings Under 500 1 Wang Joshua (8,HICKORY GROVE ELEMENTARY, DUNLAP) 455 4.0 12.5 14.0 11.0 41.0 2 Hunter Matthew (38,EPIPHANY, NORMAL) 103 4.0 11.5 12.5 12.0 40.0 For Ratings Under 400 1 Ash Keaton (25,THOMAS METCALF, NORMAL) 125 3.5 16.0 18.5 11.0 54.5 2 McCaleB Christopher (37,HUDSN) 107 3.5 15.0 17.5 11.0 50.0 For Ratings Under 300 1 Manness Will (31,EPIPHANY, NORMAL) 112 3.5 12.0 14.5 10.0 44.5 2 Dowling Tyler (18,PRNNO) 202 3.5 11.5 12.5 9.0 42.5 For Ratings Under 200 1 Kakhandki Manini (19,STEVENSON, BLOOMINGTON) 174 3.0 12.5 14.0 10.0 41.5 2 Clark Summer (30,EPIPHANY, NORMAL) 112 3.0 11.0 13.0 8.5 40.5 27TH ANNUAL MARTIN LUTHER KING DAY TOURNAMENT -- Lower PrimaryTeam Standings, Page 1 Plc Code Name (Players:Top 4 used) Score Solk Cum CumOp SBx2 1 MTCNO THOMAS METCALF, NORMAL (17) 14.5 63.0 46.0 199.5 78.5 Matejka Cole (4.0,515) Thome -

Likely to Be Funded Transportation System

Table 2: Likely to be Funded Transportation System Project # Project Description Project Extent Project Elements Priority Further Study Identify and evaluate circulation options to reduce motor OR 213/Beavercreek Road Refinement OR 213 from Redland Road to Molalla D0 vehicle congestion along the corridor. Explore alternative Short-term Plan Avenue mobility targets. Identify and evaluate circulation options to reduce motor I-205 at the OR 99E and OR 213 Ramp vehicle congestion at the interchanges. Explore alternative D00 I-205 Refinement Plan Short-term Terminals mobility targets, and consider impacts related to a potential MMA Designation for the Oregon City Regional Center. Driving Solutions (Intersection and Street Management- see Figure 16) Molalla Avenue from Washington Street to Molalla Avenue/ Beavercreek Road Deploy adaptive signal timing that adjusts signal timings to D1 Gaffney Lane; Beavercreek Road from Molalla Short-term Adaptive Signal Timing match real-time traffic conditions. Avenue to Maple Lane Road Option 1: Convert 14th Street to one-way eastbound between McLoughlin Boulevard and John Adams Street: • Convert the Main Street/14th Street intersection to all-way stop control (per project D13). • From McLoughlin Boulevard to Main Street, 14th Street would be restriped to include two 12-foot eastbound travel lanes, a six-foot eastbound bike lane, a six-foot westbound contra-flow bike lane, and an eight-foot landscaping buffer on the north side • From Main Street to Washington Street, 14th Street would be restriped to include