Admissibility: Understanding Types and Sources of Electronic Evidence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10.9 the Right to Cross-Examination

Minnesota Administrative Procedure Chapter 10. Evidence Latest Revision: 2014 10.9 THE RIGHT TO CROSS-EXAMINATION The APA guarantees all parties to a contested case the opportunity to cross- examine: “Every party or agency shall have the right of cross-examination of witnesses who testify, and shall have the right to submit rebuttal evidence.”1 The OAH rules affirm this right2 and extend it to include the right to call an adverse party for cross-examination as part of a party's case in chief.3 In the case of multiple parties, the sequence of cross-examination is determined by the ALJ.4 While application of the right to cross-examine is a simple matter in the case of witnesses who testify, does the existence of this right prevent the use of evidence from witnesses who do not give oral testimony? In short, is it ever proper to receive written evidence5 in contested cases, sworn or unsworn, offered by a party who fails to call the author of the written evidence. In Richardson v. Perales, the United States Supreme Court held that where the written evidence consisted of unsworn statements of medical experts, receipt of the evidence was proper.6 Perales involved a claim for social security disability benefits based on a back injury. At the hearing, Perales offered the oral testimony of a general practitioner who had examined him. The government countered with written medical reports, containing observations and conclusions of four specialists who had examined Perales in connection with his claim at various times.7 The reports were received over several objections by Perales's counsel, including hearsay and lack of an opportunity to cross-examine. -

The Changing Face of the Rule Against Hearsay in English Law

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Review Akron Law Journals July 2015 The hC anging Face of the Rule Against Hearsay in English Law R. A. Clark Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the Evidence Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Clark, R. A. (1988) "The hC anging Face of the Rule Against Hearsay in English Law," Akron Law Review: Vol. 21 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol21/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Clark: English Rule Against Hearsay THE CHANGING FACE OF THE RULE AGAINST HEARSAY IN ENGLISH LAW by R.A. CLARK* The rule against hearsay has always been surrounded by an aura of mystery and has been treated with excessive reverence by many English judges. Traditionally the English courts have been reluctant to allow any development in the exceptions to this exclusionary rule, regarding hearsay evidence as being so dangerous that even where it appears to be of a high pro- bative calibre it should be excluded at all costs. -

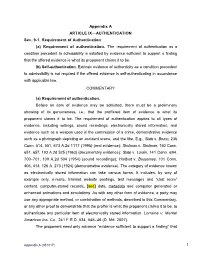

Appendix a ARTICLE IX—AUTHENTICATION Sec. 9-1

Appendix A ARTICLE IX—AUTHENTICATION Sec. 9-1. Requirement of Authentication (a) Requirement of authentication. The requirement of authentication as a condition precedent to admissibility is satisfied by evidence sufficient to support a finding that the offered evidence is what its proponent claims it to be. (b) Self-authentication. Extrinsic evidence of authenticity as a condition precedent to admissibility is not required if the offered evidence is self-authenticating in accordance with applicable law. COMMENTARY (a) Requirement of authentication. Before an item of evidence may be admitted, there must be a preliminary showing of its genuineness, i.e., that the proffered item of evidence is what its proponent claims it to be. The requirement of authentication applies to all types of evidence, including writings, sound recordings, electronically stored information, real evidence such as a weapon used in the commission of a crime, demonstrative evidence such as a photograph depicting an accident scene, and the like. E.g., State v. Bruno, 236 Conn. 514, 551, 673 A.2d 1117 (1996) (real evidence); Shulman v. Shulman, 150 Conn. 651, 657, 193 A.2d 525 (1963) (documentary evidence); State v. Lorain, 141 Conn. 694, 700–701, 109 A.2d 504 (1954) (sound recordings); Hurlburt v. Bussemey, 101 Conn. 406, 414, 126 A. 273 (1924) (demonstrative evidence). The category of evidence known as electronically stored information can take various forms. It includes, by way of example only, e-mails, Internet website postings, text messages and “chat room” content, computer-stored records, [and] data, metadata and computer generated or enhanced animations and simulations. As with any other form of evidence, a party may use any appropriate method, or combination of methods, described in this Commentary, or any other proof to demonstrate that the proffer is what the proponent claims it to be, to authenticate any particular item of electronically stored information. -

Evidence (Real & Demonstrative)

Evidence (Real & Demonstrative) E. Tyron Brown Hawkins Parnell Thackston & Young LLP Atlanta, Georgia 30308 I. TYPES OF EVIDENCE There are four types of evidence in a legal action: A. Testimonial; B. Documentary; C. Real, and; D. Demonstrative. A. TESTIMONIAL EVIDENCE Testimonial evidence, which is the most common type of evidence,. is when a witness is called to the witness stand at trial and, under oath, speaks to a jury about what the witness knows about the facts in the case. The witness' testimony occurs through direct examination, meaning the party that calls that witness to the stand asks that person questions, and through cross-examination which is when the opposing side has the chance to cross-examine the witness possibly to bring-out problems and/or conflicts in the testimony the witness gave on direct examination. Another type of testimonial evidence is expert witness testimony. An expert witness is a witness who has special knowledge in a particular area and testifies about the expert's conclusions on a topic. ln order to testify at trial, proposed witnesses must be "competent" meaning: 1. They must be under oath or any similar substitute; 2. They must be knowledgeable about what they are going to testify. This means they must have perceived something with their senses that applies to the case in question; 3. They must have a recollection of what they perceived; and 4. They must be in a position to relate what they communicated 1 Testimonial evidence is one of the only forms of proof that does not need reinforcing evidence for it to be admissible in court. -

Decision on Guidelines for the Admission of Evidence Through Witnesses

IT -95-5/18-T 35844 UNITED D 35844 - D 35835 19 May 2010 PvK NATIONS International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Case No.: IT-95-51l8-T Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Date: 19 May 2010 Committed in the Territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991 Original: English IN THE TRIAL CHAMBER Before: Judge O-Gon Kwon, Presiding Judge Judge Howard Morrison Judge Melville Baird Judge Flavia Lattanzi, Reserve Judge Registrar: Mr. John Hocking Decision of: 19 May 2010 PROSECUTOR v. RADOVAN KARADZIC PUBLIC DECISION ON GUIDELINES FOR THE ADMISSION OF EVIDENCE THROUGH WITNESSES Office of the Prosecutor Mr. Alan Tieger Ms. Hildegard Uertz-Retzlaff The Accused Standby Counsel Mr. Radovan Karadzi6 Mr. Richard Harvey 35843 THIS TRIAL CHAMBER of the International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991 ("Tribunal"), ex proprio motu, issues this decision in relation to the admission of evidence through witnesses. I. Background and Submissions 1. On 6 May 2010, the Presiding Judge informed the parties of general principles that would apply in this case to the admissibility of evidence through a witness and, in accordance with those principles, denied the admission into evidence of a number of documents tendered by the Accused during the cross-examination of the witness Fatima Zaimovi6 on 5 May 2010. 1 2. On 7 May 2010, the Accused's legal advisor, Mr. Peter Robinson, made an oral request to the Chamber to "revisit" the decisions it made on 6 May 2010 denying the admission of several documents tendered during the cross-examination of Fatima Zaimovi6 ("Request,,). -

Decision on Prosecution Motion to Admit Documentary Evidence

UNITED NATIONS International Tribunal for the Case No.: IT-05-87-T Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations Date: 10 October 2006 of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991 Original: English IN THE TRIAL CHAMBER Before: Judge Iain Bonomy, Presiding Judge Ali Nawaz Chowhan Judge Tsvetana Kamenova Judge Janet Nosworthy, Reserve Judge Registrar: Mr. Hans Holthuis Decision of: 10 October 2006 PROSECUTOR DECISION ON PROSECUTION MOTION TO ADMIT DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE Office of the Prosecutor Mr. Thomas Hannis Mr. Chester Stamp Ms. Christina Moeller Ms. Patricia Fikirini Mr. Mathias Marcussen Counsel for the Accused Mr. Eugene O'Sullivan and Mr. Slobodan ZeEeviC for Mr. Milan MilutinoviC Mr. Toma Fila and Mr. Vladimir PetroviC for Mr. Nikola Sainovid Mr. Tomislav ViSnjiC and Mr. Norman Sepenuk for Mr. Dragoljub OjdaniC Mr. John Ackerman and Mr. Aleksandar AleksiC for Mr. Nebojsa PavkoviC Mr. Mihajlo BakraE and Mr. Duro CepiC for Mr. Vladimir LazareviC Mr. Branko LukiC and Mr. Dragan Ivetic for Mr. Sreten LukiC THIS TRIAL CHAMBER of the International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Tenitory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991 ("Tribunal") is seised of several submissions from the parties, which request certain relief with regard to documentary evidence tendered by the Prosecution. Accused MilutinoviC, SainoviC, OjdaniC, PavkoviC, LazareviC, and LukiC (collectively, "Accused) object to the admission of this evidence on several grounds, while the Office of the Prosecutor ("Prosecution") counters that all should be admitted in whole or in part. The Trial Chamber hereby renders its decision. -

State of New York Court of Appeals

State of New York OPINION Court of Appeals This opinion is uncorrected and subject to revision before publication in the New York Reports. No. 31 Andrew Kolchins, Respondent, v. Evolution Markets, Inc., Appellant. David B. Wechsler, for appellant. Jyotin Hamid, for respondent. STEIN, J.: The issue on this appeal is whether the documentary evidence proffered by defendant Evolution Markets, Inc. on its motion to dismiss pursuant to CPLR 3211 (a) (1) conclusively refuted plaintiff Andrew Kolchins’s breach of contract claims. We hold that defendant has not met its burden and we, therefore, affirm. - 1 - - 2 - No. 31 - I - Defendant is a corporation that structures transactions and provides brokerage and advisory services in the global environmental and energy commodity marketplace. In 2005, plaintiff joined defendant as a commodities broker and, in 2006, the parties entered into an employment agreement with a three-year term. Subsequently, in 2009, plaintiff and defendant entered into another three-year employment agreement with an “Ending Date” of August 31, 2012. Under the 2009 Agreement, plaintiff was an “at will” employee; however, if defendant terminated him without “Cause” or he ceased employment for “Good Reason,” and he complied with certain restrictive covenants, he would be paid his base salary through the Ending Date, as well as a “Special Non-Compete Payment” thereafter.1 His compensation package included a $200,000 annual base salary and a “Sign on Bonus” of $750,000. Separately, the Agreement set forth terms under which plaintiff was eligible to receive a “Production Bonus” that was “based on [his] performance” each trimester, and which would be “paid within two months of the close of a given trimester.”2 The 2009 Agreement also provided for minimum “Guaranteed Compensation” of $750,000 each contract year. -

California State Rules of Evidence

Introducing Digital Evidence in California State Courtsi Introducing Documentary and Electronic Evidence In order to introduce documentary and electronic evidence obtained in compliance with California Electronic Communication Privacy Act (Penal Code §§ 1546.1 and 1546. 2) in court, it must have four components: 1) it must be relevant. 2) it must be authenticated. 3) its contents must not be inadmissible hearsay; and 4) it must withstand a "best evidence" objection. If the digital evidence contains “metadata” (data about the data such as when the document was created or last accessed, or when and where a photo was taken) proponents will to need to address the metadata separately, and prepare an additional foundation for it. I. Relevance Only relevant evidence is admissible. (Evid. Code, § 350.) To be "relevant," evidence must have a tendency to prove or disprove any disputed fact, including credibility. (Evid. Code, § 210.) All relevant evidence is admissible, except as provided by statute. (Evid. Code, § 351.) For digital evidence to be relevant, the defendant typically must be tied to the evidence, usually as the sender or receiver. With a text message, for example, the proponent must tie the defendant to either the phone number that sent, or the phone number that received, the text. If the defendant did not send or receive/read the text, the text-as-evidence might lack relevance. In addition; evidence that the defendant is tied to the number can be circumstantial. And evidence that the defendant received and read a text also can be circumstantial. Theories of admissibility include: Direct evidence of a crime Credibility of witnesses Circumstantial evidence of a Impeachment crime Negates or forecloses a defense Identity of perpetrator Basis of expert opinion Intent of perpetrator Lack of mistake Motive II. -

Scientific Documentary Evidence in Criminal Trials

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 23 Article 14 Issue 2 July--August Summer 1932 Scientific oD cumentary Evidence in Criminal Trials C. Ainsworth Mitchell Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation C. Ainsworth Mitchell, Scientific ocD umentary Evidence in Criminal Trials, 23 Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 336 (1932-1933) This Criminology is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Editorial Note-The section which follows has been added to this Journal in order to present to former subscribers of the American Journal of Police Science a department in which they may find material of a type not ordinarily available outside of the pages of that Journal. Articles of a more general nature received as contributions to the American Journal of Police Science will be printed in the sections devoted to "Contributed Articles," and "Briefer Contributions." Reviews of books in the field of Police Science will appear under the "Book Reviews" section in this and subsequent issues, and notes on subjects of current interest in this field will appear in the "Current Notes" section. CALVIN GODDARD. POLICE SCIENCE b 0 1930 CALVIN GODDARD, [Ed.] SCIENTIFIC DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE IN CRIMINAL TRIALS C. AINSWORTH MITCHELL Editor's Note: The following paper was originally read on July 4, 1931, at a meeting of the North of England Section of the Society of Public Analysts. -

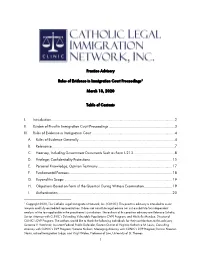

1 Practice Advisory Rules of Evidence in Immigration Court Proceedings1 March 13, 2020 Table of Contents I. Introduction

Practice Advisory Rules of Evidence in Immigration Court Proceedings1 March 13, 2020 Table of Contents I. Introduction .........................................................................................................................................2 II. Burden of Proof in Immigration Court Proceedings .........................................................................3 III. Rules of Evidence in Immigration Court ............................................................................................4 A. Rules of Evidence Generally ..........................................................................................................4 B. Relevance ........................................................................................................................................7 C. Hearsay, Including Government Documents Such as Form I-213 ..............................................8 D. Privilege; Confidentiality Protections ........................................................................................... 15 E. Personal Knowledge; Opinion Testimony .................................................................................. 17 F. Fundamental Fairness .................................................................................................................. 18 G. Beyond the Scope ....................................................................................................................... 19 H. Objections Based on Form of the Question During Witness Examination .............................. -

Chain of Custody and Identification of Real Evidence

Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons Faculty Publications 1983 Chain of Custody and Identification of Real videnceE Paul C. Giannelli Case Western University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Evidence Commons Repository Citation Giannelli, Paul C., "Chain of Custody and Identification of Real videnceE " (1983). Faculty Publications. 451. https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/faculty_publications/451 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. -, ·-. TE Vol. 6, No.2 March-April, 1983 CHAIN OF CUSTODY AND THE IDENTIFICATION OF REAL EVIDENCE Paul C. Giannelli Professor of Law Case Western Reserve University Authentication or identification of real evidence exhibit if its probative value was substantially out refers to the requirement of proving that the evi weighed by the danger of unfair prejudice or dence is what it purports to be. McCormick wrote: misleading the jury. Fed. R. Evid. 403. "When real evidence is offered an adequate foun dation for admission will require testimony first READILY IDENTIFIABLE EVIDENCE that the object offered is th.e object which was in volved in the incident, and further that the condi An item of evidence can be identified directly by tion of the object is substantially unchanged." C. a witness with personal knowledge who recognizes McCormick, Evidence 527 (2d ed. 1972). -

Evidence Rules Refresher and Evidence Objections at Trial Professor Robert P

10/7/2013 Evidence Rules Refresher and Evidence Objections at Trial Professor Robert P. Mosteller J. Dickson Phillips Distinguished Professor of Law University of North Carolina School of Law I. Objections that Make the Record Helpful From the perspective of a former public defender with experience mostly as a trial law but also having spent a year handling appeals and a law professor with years of reading appellate decisions for evidence articles and books, I have a dual focus. My primary advice is to think of evidence law in terms of enhancing your chances of an acquittal or a positive outcome in the trial court. As to evidence law generally, concentrate principally on the “here and now” at trial. Lawyers don’t try cases with multiple, elegant objections in order to win a reversal on appeal. It’s not accidental that most evidence discussions are near the end of opinions in criminal cases. The winning issues usually appear toward the beginning of the opinion, and pure evidence errors are not a major source of reversals. However, while defense attorneys generally should focus on winning the evidence point at trial and handling objections consistent with their trial strategy, a second goal should be to give substantial issues to the appellate lawyer in case you do not prevail at trial. You can enhance those prospects on appeal and unfortunately can definitely harm them by how effectively you prefect and preserve issues for review. Under Federal Rule 103(a)(1), if you’re on the losing end of an objection at trial that admits evidence (that is, you object and the judge states, “overruled”), you need to have objected in a timely manner and stated correctly the grounds for objection.