California State Rules of Evidence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evidence History, the New Trace Evidence, and Rumblings in the Future of Proof Robert P

University of North Carolina School of Law Carolina Law Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2006 Evidence History, the New Trace Evidence, and Rumblings in the Future of Proof Robert P. Mosteller University of North Carolina School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Publication: Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Evidence History, the New Trace Evidence, and Rumblings in the Future of Proof Robert P. Mosteller* I. INTRODUCTION This paper is in two parts. The first part is about developments in the rules of evidence and particularly about developments in the Federal Rules of Evidence, which have had a major impact on evidence rules in many states. This part turns out to be largely about the past because my sense is that the impact of changes in the formal rules of evidence, which were substantial, are largely historic. In one area, however, significant future changes in the formal rules seem possible: those that may be made as a result of the Supreme Court’s decision in Crawford v. Washington,1 which dramatically changed confrontation and may unleash hearsay reformulation. The second part deals with my sense that technological and scientific advances may have a dramatic impact in altering the way cases, particularly criminal cases, are proved and evaluated in the future. -

10.9 the Right to Cross-Examination

Minnesota Administrative Procedure Chapter 10. Evidence Latest Revision: 2014 10.9 THE RIGHT TO CROSS-EXAMINATION The APA guarantees all parties to a contested case the opportunity to cross- examine: “Every party or agency shall have the right of cross-examination of witnesses who testify, and shall have the right to submit rebuttal evidence.”1 The OAH rules affirm this right2 and extend it to include the right to call an adverse party for cross-examination as part of a party's case in chief.3 In the case of multiple parties, the sequence of cross-examination is determined by the ALJ.4 While application of the right to cross-examine is a simple matter in the case of witnesses who testify, does the existence of this right prevent the use of evidence from witnesses who do not give oral testimony? In short, is it ever proper to receive written evidence5 in contested cases, sworn or unsworn, offered by a party who fails to call the author of the written evidence. In Richardson v. Perales, the United States Supreme Court held that where the written evidence consisted of unsworn statements of medical experts, receipt of the evidence was proper.6 Perales involved a claim for social security disability benefits based on a back injury. At the hearing, Perales offered the oral testimony of a general practitioner who had examined him. The government countered with written medical reports, containing observations and conclusions of four specialists who had examined Perales in connection with his claim at various times.7 The reports were received over several objections by Perales's counsel, including hearsay and lack of an opportunity to cross-examine. -

The Changing Face of the Rule Against Hearsay in English Law

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Review Akron Law Journals July 2015 The hC anging Face of the Rule Against Hearsay in English Law R. A. Clark Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the Evidence Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Clark, R. A. (1988) "The hC anging Face of the Rule Against Hearsay in English Law," Akron Law Review: Vol. 21 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol21/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Clark: English Rule Against Hearsay THE CHANGING FACE OF THE RULE AGAINST HEARSAY IN ENGLISH LAW by R.A. CLARK* The rule against hearsay has always been surrounded by an aura of mystery and has been treated with excessive reverence by many English judges. Traditionally the English courts have been reluctant to allow any development in the exceptions to this exclusionary rule, regarding hearsay evidence as being so dangerous that even where it appears to be of a high pro- bative calibre it should be excluded at all costs. -

Ohio Rules of Evidence

OHIO RULES OF EVIDENCE Article I GENERAL PROVISIONS Rule 101 Scope of rules: applicability; privileges; exceptions 102 Purpose and construction; supplementary principles 103 Rulings on evidence 104 Preliminary questions 105 Limited admissibility 106 Remainder of or related writings or recorded statements Article II JUDICIAL NOTICE 201 Judicial notice of adjudicative facts Article III PRESUMPTIONS 301 Presumptions in general in civil actions and proceedings 302 [Reserved] Article IV RELEVANCY AND ITS LIMITS 401 Definition of “relevant evidence” 402 Relevant evidence generally admissible; irrelevant evidence inadmissible 403 Exclusion of relevant evidence on grounds of prejudice, confusion, or undue delay 404 Character evidence not admissible to prove conduct; exceptions; other crimes 405 Methods of proving character 406 Habit; routine practice 407 Subsequent remedial measures 408 Compromise and offers to compromise 409 Payment of medical and similar expenses 410 Inadmissibility of pleas, offers of pleas, and related statements 411 Liability insurance Article V PRIVILEGES 501 General rule Article VI WITNESS 601 General rule of competency 602 Lack of personal knowledge 603 Oath or affirmation Rule 604 Interpreters 605 Competency of judge as witness 606 Competency of juror as witness 607 Impeachment 608 Evidence of character and conduct of witness 609 Impeachment by evidence of conviction of crime 610 Religious beliefs or opinions 611 Mode and order of interrogation and presentation 612 Writing used to refresh memory 613 Impeachment by self-contradiction -

Proving the Integrity of Digital Evidence with Time Chet Hosmer, President & CEO Wetstone Technologies, Inc

International Journal of Digital Evidence Spring 2002 Volume 1, Issue 1 Proving the Integrity of Digital Evidence with Time Chet Hosmer, President & CEO WetStone Technologies, Inc. Background During the latter half of the 20th century, a dramatic move from paper to bits occurred. Our use of digital communication methods such as the world-wide-web and e-mail have dramatically increased the amount of information that is routinely stored in only a digital form. On October 1, 2000 the Electronic Signatures in National and Global Commerce Act was enacted, allowing transactions signed electronically to be enforceable in a court of law. (Longley) The dramatic move from paper to bits combined with the ability and necessity to bring digital data to court, however, creates a critical question. How do we prove the integrity of this new form of information known as “digital evidence”? Digital evidence originates from a multitude of sources including seized computer hard-drives and backup media, real-time e-mail messages, chat-room logs, ISP records, web-pages, digital network traffic, local and virtual databases, digital directories, wireless devices, memory cards, and digital cameras. The trust worthiness of this digital data is a critical question that digital forensic examiners must consider. Many vendors provide technology solutions to extract this digital data from these devices and networks. Once the extraction of the digital evidence has been accomplished, protecting the digital integrity becomes of paramount concern for investigators, prosecutors and those accused. The ease with which digital evidence can be altered, destroyed, or manufactured in a convincing way – by even novice computer users – is alarming. -

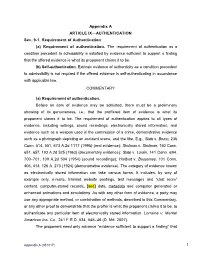

Appendix a ARTICLE IX—AUTHENTICATION Sec. 9-1

Appendix A ARTICLE IX—AUTHENTICATION Sec. 9-1. Requirement of Authentication (a) Requirement of authentication. The requirement of authentication as a condition precedent to admissibility is satisfied by evidence sufficient to support a finding that the offered evidence is what its proponent claims it to be. (b) Self-authentication. Extrinsic evidence of authenticity as a condition precedent to admissibility is not required if the offered evidence is self-authenticating in accordance with applicable law. COMMENTARY (a) Requirement of authentication. Before an item of evidence may be admitted, there must be a preliminary showing of its genuineness, i.e., that the proffered item of evidence is what its proponent claims it to be. The requirement of authentication applies to all types of evidence, including writings, sound recordings, electronically stored information, real evidence such as a weapon used in the commission of a crime, demonstrative evidence such as a photograph depicting an accident scene, and the like. E.g., State v. Bruno, 236 Conn. 514, 551, 673 A.2d 1117 (1996) (real evidence); Shulman v. Shulman, 150 Conn. 651, 657, 193 A.2d 525 (1963) (documentary evidence); State v. Lorain, 141 Conn. 694, 700–701, 109 A.2d 504 (1954) (sound recordings); Hurlburt v. Bussemey, 101 Conn. 406, 414, 126 A. 273 (1924) (demonstrative evidence). The category of evidence known as electronically stored information can take various forms. It includes, by way of example only, e-mails, Internet website postings, text messages and “chat room” content, computer-stored records, [and] data, metadata and computer generated or enhanced animations and simulations. As with any other form of evidence, a party may use any appropriate method, or combination of methods, described in this Commentary, or any other proof to demonstrate that the proffer is what the proponent claims it to be, to authenticate any particular item of electronically stored information. -

American Journal of Trial Advocacy Authentication of Social Media Evidence.Pdf

Authentication of Social Media Evidence Honorable Paul W. Grimm† Lisa Yurwit Bergstrom†† Melissa M. O’Toole-Loureiro††† Abstract The authentication of social media evidence has become a prevalent issue in litigation today, creating much confusion and disarray for attorneys and judges. By exploring the current inconsistencies among courts’ de- cisions, this Article demonstrates the importance of the interplay between Federal Rules of Evidence 901, 104(a), 104(b), and 401—all essential rules for determining the admissibility and authentication of social media evidence. Most importantly, this Article concludes by offering valuable and practical suggestions for attorneys to authenticate social media evidence successfully. Introduction Ramon Stoppelenburg traveled around the world for nearly two years, visiting eighteen countries in which he “personally met some 10,000 people on the road, slept in 500 different beds, ate some 1,500 meals[,] and had some 600 showers,” without spending any money.1 Instead, his blog, Let-Me-Stay-For-A-Day.com, fueled his travels.2 He spent time each evening updating the blog, encouraging people to invite him to stay † B.A. (1973), University of California; J.D. (1976), University of New Mexico School of Law. Paul W. Grimm is a District Judge serving on the United States District Court for the District of Maryland. In September 2009, the Chief Justice of the United States appointed Judge Grimm to serve as a member of the Advisory Committee for the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Judge Grimm also chairs the Advisory Committee’s Discovery Subcommittee. †† B.A. (1998), Amherst College; J.D. (2008), University of Baltimore School of Law. -

Evidence (Real & Demonstrative)

Evidence (Real & Demonstrative) E. Tyron Brown Hawkins Parnell Thackston & Young LLP Atlanta, Georgia 30308 I. TYPES OF EVIDENCE There are four types of evidence in a legal action: A. Testimonial; B. Documentary; C. Real, and; D. Demonstrative. A. TESTIMONIAL EVIDENCE Testimonial evidence, which is the most common type of evidence,. is when a witness is called to the witness stand at trial and, under oath, speaks to a jury about what the witness knows about the facts in the case. The witness' testimony occurs through direct examination, meaning the party that calls that witness to the stand asks that person questions, and through cross-examination which is when the opposing side has the chance to cross-examine the witness possibly to bring-out problems and/or conflicts in the testimony the witness gave on direct examination. Another type of testimonial evidence is expert witness testimony. An expert witness is a witness who has special knowledge in a particular area and testifies about the expert's conclusions on a topic. ln order to testify at trial, proposed witnesses must be "competent" meaning: 1. They must be under oath or any similar substitute; 2. They must be knowledgeable about what they are going to testify. This means they must have perceived something with their senses that applies to the case in question; 3. They must have a recollection of what they perceived; and 4. They must be in a position to relate what they communicated 1 Testimonial evidence is one of the only forms of proof that does not need reinforcing evidence for it to be admissible in court. -

Job Title – Department Senior Consultant Forensics and Technology

Job title here Job title – Department Senior Consultant Forensics and Technology Control Risks is a specialist risk consultancy that helps to create secure, compliant and resilient organisations in an age of ever-changing risk. Working across disciplines, technologies and geographies, everything we do is based on our belief that taking risks is essential to our clients’ success. We provide our clients with the insight to focus resources and ensure they are prepared to resolve the issues and crises that occur in any ambitious global organisation. We go beyond problem-solving and give our clients the insight and intelligence they need to realise opportunities and grow. From the boardroom to the remotest location, we have developed an unparalleled ability to bring order to chaos and reassurance to anxiety. Our people Working with our clients our people are given direct responsibility, career development and the opportunity to work collaboratively on fascinating projects in a rewarding and inclusive global environment. Location Shanghai Engagement Full-time Department Regional Technology (F&T) Manager Principal, Regional Technology To drive & manage the continued development of our digital forensic technology Job purpose capabilities in China Tasks Project Work and responsibilities Lead in the development and management of the team’s forensic technologies service offerings and capabilities. Play a supporting role in the management of complex fraud and corruption investigations, particularly those involving the use of forensic technologies. Consult and understand the requirements of clients in relation to computer forensics. Perform computer forensics activities including digital evidence preservation, analysis, data recovery, tape recovery, electronic mail extraction, and database examination. -

Manual on Best Practices for Authenticating Digital Evidence

BEST PRACTICES FOR AUTHENTICATING DIGITAL EVIDENCE HON. PAUL W. GRIMM United States District Judge for the District of Maryland former member of the Judicial Conference Advisory Committee on Civil Rules GREGORY P. JOSEPH, ESQ. Partner, Joseph Hage Aaronson, New York City former member of the Judicial Conference Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules DANIEL J. CAPRA Reed Professor of Law, Fordham Law School Reporter to the Judicial Conference Advisory Committee on Evidence Rules The publisher is not engaged in rendering legal or other professional advice, and this publication is not a substitute for the advice of an attorney. If you require legal or other expert advice, you should seek the services of a competent attorney or other professional. © 2016 LEG, Inc. d/b/a West Academic 444 Cedar Street, Suite 700 St. Paul, MN 55101 1-877-888-1330 Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-68328-471-0 [No claim of copyright is made for official U.S. government statutes, rules or regulations.] TABLE OF CONTENTS Best Practices for Authenticating Digital Evidence ..................... 1 I. Introduction ........................................................................................ 1 II. An Introduction to the Principles of Authentication for Electronic Evidence: The Relationship Between Rule 104(a) and 104(b) ........ 2 III. Relevant Factors for Authenticating Digital Evidence ................... 6 A. Emails ......................................................................................... 7 B. Text Messages ......................................................................... -

Consultant Vendor Service Rider Template

RIDER TO [CONSULTANT] [VENDOR] AGREEMENT Rider to [Consultant] [Vendor] Agreement dated _____________, 20____ (“Agreement”) by and between [FULL LEGAL NAME OF CONSULTANT OR VENDOR] [(“Consultant”)] [(“Vendor”)] and Pace University (“Pace”). The following clauses are hereby incorporated and made a part of the Agreement, to either replace or supplement the terms thereof. In the event of any conflict or discrepancy between the terms of this Rider and the terms of the Agreement, the terms of this Rider shall control. 1. Expertise. [Consultant] [Vendor] represents to Pace that [Consultant] [Vendor] has sufficient staff available to provide the services to be delivered under the Agreement and that all individuals providing such services have the background, training, and experience to provide the services to be delivered under the Agreement. 2. Expenses. Provided that Pace shall first have received from [Consultant] [Vendor] an original of the Agreement that shall have been countersigned by an authorized [Consultant] [Vendor] signatory, [Consultant] [Vendor] shall be paid, as its sole and exclusive consideration hereunder, the fee(s) described in the Agreement upon Pace’s receipt from [Consultant] [Vendor] of an invoice that, in form and substance satisfactory to Pace, shall describe the services that [Consultant] [Vendor] shall have provided to Pace in the period during the Term for which [Consultant] [Vendor] seeks payment. Except as specifically provided in the Agreement, all expenses shall be borne by [Consultant] [Vendor]. [Consultant] [Vendor] shall only be entitled to reimbursement of reasonable expenses that are actually incurred and allocable solely to the Work provided to Pace pursuant to the Agreement. [Consultant] [Vendor] shall provide such evidence as Pace may reasonably request in support of [Consultant’s] [Vendor’s] claims for expense reimbursement. -

Decision on Guidelines for the Admission of Evidence Through Witnesses

IT -95-5/18-T 35844 UNITED D 35844 - D 35835 19 May 2010 PvK NATIONS International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Case No.: IT-95-51l8-T Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Date: 19 May 2010 Committed in the Territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991 Original: English IN THE TRIAL CHAMBER Before: Judge O-Gon Kwon, Presiding Judge Judge Howard Morrison Judge Melville Baird Judge Flavia Lattanzi, Reserve Judge Registrar: Mr. John Hocking Decision of: 19 May 2010 PROSECUTOR v. RADOVAN KARADZIC PUBLIC DECISION ON GUIDELINES FOR THE ADMISSION OF EVIDENCE THROUGH WITNESSES Office of the Prosecutor Mr. Alan Tieger Ms. Hildegard Uertz-Retzlaff The Accused Standby Counsel Mr. Radovan Karadzi6 Mr. Richard Harvey 35843 THIS TRIAL CHAMBER of the International Tribunal for the Prosecution of Persons Responsible for Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law Committed in the Territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991 ("Tribunal"), ex proprio motu, issues this decision in relation to the admission of evidence through witnesses. I. Background and Submissions 1. On 6 May 2010, the Presiding Judge informed the parties of general principles that would apply in this case to the admissibility of evidence through a witness and, in accordance with those principles, denied the admission into evidence of a number of documents tendered by the Accused during the cross-examination of the witness Fatima Zaimovi6 on 5 May 2010. 1 2. On 7 May 2010, the Accused's legal advisor, Mr. Peter Robinson, made an oral request to the Chamber to "revisit" the decisions it made on 6 May 2010 denying the admission of several documents tendered during the cross-examination of Fatima Zaimovi6 ("Request,,).