Research Article the Impact of Urban Transit Systems on Property Values: a Model and Some Evidences from the City of Naples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rough Guide to Naples & the Amalfi Coast

HEK=> =K?:;I J>;HEK=>=K?:;je CVeaZh i]Z6bVaÒ8dVhi D7FB;IJ>;7C7B<?9E7IJ 7ZcZkZcid BdcYgV\dcZ 8{ejV HVc<^dg\^d 8VhZgiV HVciÉ6\ViV YZaHVcc^d YZ^<di^ HVciVBVg^V 8{ejVKiZgZ 8VhiZaKdaijgcd 8VhVaY^ Eg^cX^eZ 6g^Zcod / AV\dY^EVig^V BVg^\a^Vcd 6kZaa^cd 9WfeZ_Y^_de CdaV 8jbV CVeaZh AV\dY^;jhVgd Edoojda^ BiKZhjk^jh BZgXVidHVcHZkZg^cd EgX^YV :gXdaVcd Fecf[__ >hX]^V EdbeZ^ >hX]^V IdggZ6ccjco^ViV 8VhiZaaVbbVgZY^HiVW^V 7Vnd[CVeaZh GVkZaad HdggZcid Edh^iVcd HVaZgcd 6bVa[^ 8{eg^ <ja[d[HVaZgcd 6cVX{eg^ 8{eg^ CVeaZh I]Z8Vbe^;aZ\gZ^ Hdji]d[CVeaZh I]Z6bVa[^8dVhi I]Z^haVcYh LN Cdgi]d[CVeaZh FW[ijkc About this book Rough Guides are designed to be good to read and easy to use. The book is divided into the following sections, and you should be able to find whatever you need in one of them. The introductory colour section is designed to give you a feel for Naples and the Amalfi Coast, suggesting when to go and what not to miss, and includes a full list of contents. Then comes basics, for pre-departure information and other practicalities. The guide chapters cover the region in depth, each starting with a highlights panel, introduction and a map to help you plan your route. Contexts fills you in on history, books and film while individual colour sections introduce Neapolitan cuisine and performance. Language gives you an extensive menu reader and enough Italian to get by. 9 781843 537144 ISBN 978-1-84353-714-4 The book concludes with all the small print, including details of how to send in updates and corrections, and a comprehensive index. -

Bagnoli, Fuorigrotta, Soccavo, Pianura, Piscinola, Chiaiano, Scampia

Comune di Napoli - Bando Reti - legge 266/1997 art. 14 – Programma 2011 Assessorato allo Sviluppo Dipartimento Lavoro e Impresa Servizio Impresa e Sportello Unico per le Attività Produttive BANDO RETI Legge 266/97 - Annualità 2011 Agevolazioni a favore delle piccole imprese e microimprese operanti nei quartieri: Bagnoli, Fuorigrotta, Soccavo, Pianura, Piscinola, Chiaiano, Scampia, Miano, Secondigliano, San Pietro a Patierno, Ponticelli, Barra, San Giovanni a Teduccio, San Lorenzo, Vicaria, Poggioreale, Stella, San Carlo Arena, Mercato, Pendino, Avvocata, Montecalvario, S.Giuseppe, Porto. Art. 14 della legge 7 agosto 1997, n. 266. Decreto del ministro delle attività produttive 14 settembre 2004, n. 267. Pagina 1 di 12 Comune di Napoli - Bando Reti - legge 266/1997 art. 14 – Programma 2011 SOMMARIO ART. 1 – OBIETTIVI, AMBITO DI APPLICAZIONE E DOTAZIONE FINANZIARIA ART. 2 – REQUISITI DI ACCESSO. ART. 3 – INTERVENTI IMPRENDITORIALI AMMISSIBILI. ART. 4 – TIPOLOGIA E MISURA DEL FINANZIAMENTO ART. 5 – SPESE AMMISSIBILI ART. 6 – VARIAZIONI ALLE SPESE DI PROGETTO ART. 7 – PRESENTAZIONE DOMANDA DI AMMISSIONE ALLE AGEVOLAZIONI ART. 8 – PROCEDURE DI VALUTAZIONE E SELEZIONE ART. 9 – ATTO DI ADESIONE E OBBLIGO ART. 10 – REALIZZAZIONE DELL’INVESTIMENTO ART. 11 – EROGAZIONE DEL CONTRIBUTO ART. 12 –ISPEZIONI, CONTROLLI, ESCLUSIONIE REVOCHE DEI CONTRIBUTI ART. 13 – PROCEDIMENTO AMMINISTRATIVO ART. 14 – TUTELA DELLA PRIVACY ART. 15 – DISPOSIZIONI FINALI Pagina 2 di 12 Comune di Napoli - Bando Reti - legge 266/1997 art. 14 – Programma 2011 Art. 1 – Obiettivi, -

Breakthrough Ceremony for Monte Olibano Tunnel on the Cumana Railway Line

BREAKTHROUGH CEREMONY FOR MONTE OLIBANO TUNNEL ON THE CUMANA RAILWAY LINE The tunnel, built by Astaldi Group, allows for the upgrading and expansion of a strategic transport infrastructure for the metropolitan area of Naples and for the whole Phlegrean catchment area Naples, 2 July 2020 – The breakthrough ceremony for Monte Olibano tunnel, which forms part of the project to upgrade and expand the Cumana Railway, was held this morning in Naples and was attended by Vincenzo De Luca , President of Campania Region , Vincenzo Figliolia , Mayor of Pozzuoli , Umberto De Gregorio, Chairman of EAV , as well as Paolo Astaldi , Chairman of Astaldi Group , and Filippo Stinellis , CEO of Astaldi Group. The new tunnel forms part of the project to double the Cumana Railway line along a section measuring approximately 5 km and includes, inter alia, works to adjust the route of the old single-track Monte Olibano tunnel, construction of new stations in Pozzuoli and Cantieri, updating of Gerolomini station and works to double the railway track for the Dazio- Cantieri section. Performance of these works will make it possible to finally complete doubling of the railway line, allowing for an underground-style transport service on the complete Cumana line, with a high frequency of trains and high safety standards. Completion of the planned upgrading and expansion of the railway is scheduled for June 2023. The network, which comprises the Cumana and Circumflegrea lines and 33 stations, serves the whole of the western part of the Naples metropolitan area and the Phlegrean catchment area, a highly-populated area that is set to expand even further as a result of the constant growth of housing and tourism. -

Metropolitane E Linee Regionali: Mappa Della

Formia Caserta Caserta Benevento Villa Literno San Marcellino Sant’Antimo Frattamaggiore Cancello Albanova Frignano Aversa Sant’Arpino Grumo Nevano 12 Acerra 11Aversa Centro Acerra Alfa Lancia 2 Aversa Ippodromo Giugliano Alfa Lancia 4 Casalnuovo igna Baiano Casoria 2 Melito 1 in costruzione Mugnano Afragola La P Talona e e co o linea 1 in costruzione Casalnuovo ont Ar erna iemont Piscinola ola P Brusciano Salice asalcist Scampia co P Prat C De Ruggier Chiaiano Par 1 11 Aeroporto Pomigliano d’ Giugliano Frullone Capodichino Volla Qualiano Colli Aminei Botteghelle Policlinico Poggioreale Materdei Madonnelle Rione Alto Centro Argine Direzionale Palasport Montedonzelli Salvator Stazione Rosa Cavour Centrale Medaglie d’Oro Villa Visconti Museo 1 Garibaldi Gianturco anni rocchia Quar v cio T esuvio Montesanto a V Quar La Piazza Olivella S.Gioeduc fficina cola to C Socca Corso Duomo T O onticelli onticelli De Meis er ollena O Quar P T T Quattro in costruzione a Barr P P C P Guindazzi fficina entr P ianura rencia raiano P C Vittorio Dante to isani ia Giornate Morghen Emanuele t v v o o o e Montesanto S.Maria Bartolo Longo Madonna dell’Arco Via del Pozzo 5 8 C Gianturco S.Giorgio Grotta Vanvitelli Fuga A Toledo S. Anastasia Università Porta 3 a Cremano del Sole Petraio Corso Vittorio Nolana S. Giorgio Cavalli di Bronzo Villa Augustea ostruzione Cimarosa Emanuele 3 12131415 Portici Bellavista Somma Vesuviana Licola B Palazzolo linea 7 in c Augusteo Municipio Immacolatella Portici Via Libertà Quarto Corso Vittorio Emanuele A Porto di Napoli Rione Trieste Ercolano Scavi Marina di Marano Corso Vittorio Ottaviano di Licola Emanuele Parco S.Giovanni Barra 2 Ercolano Miglio d’Oro Fuorigrotta Margherita ostruzione S. -

Vomero, but Right by a Funicular Ride Into the Centre

Page 66 S1 Escape: Budget break Daily Mail, Saturday, March 2, 2019 Naples for less than £100 a night WITH Mount Vesuvius looming in the distance, Mediterranean waves slapping on the harbour walls, ancient castles, trips of Pompeii and labyrinthine lanes, Naples is perfect for an intriguing weekend away. The capital of the Campania region in southern Italy is famous for its manic edginess — as well as the invention of pizza — and can be an affordable choice for a short dei Tr break ... if you know where to look. Via ibu nali aribaldi Where to stay omero G ÷ Attico Partenopeo V tation IN THE heart of the old town, this S bijou eight-room hotel/B&B is hidden at the top of an apartment Vibrant: Clockwise block; you take a lift to the fifth floor reception. Rooms have comfortable from top left, Neapolitan beds, modern art and balconies (in pizza, a traditional street some) facing Vesuvius. Organic unicular scene and minimalist breakfast is served in a bright dining F Hotel Palazzo Caracciolo room or on a suntrap terrace. B&B doubles from £61; add £17.50 for Vesuvius views (atticopartenopeo.it) ÷ Hotel Cimarosa ON A hill in the peaceful residential district of Vomero, but right by a funicular ride into the centre, Getting there Y Cimarosa is an arty hotel with 16 modern rooms. This is a great British AirwaYS has ett return flights from / G hideaway for those seeking to escape the old town’s bustle. London Gatwick to Naples alli B&B doubles from £69 from £48 (ba.com). -

DLA Piper. Details of the Member Entities of DLA Piper Are Available on the Website

EUROPEAN PPP REPORT 2009 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Report has been published with particular thanks to: The EPEC Executive and in particular, Livia Dumitrescu, Goetz von Thadden, Mathieu Nemoz and Laura Potten. Those EPEC Members and EIB staff who commented on the country reports. Each of the contributors of a ‘View from a Country’. Line Markert and Mikkel Fritsch from Horten for assistance with the report on Denmark. Andrei Aganimov from Borenius & Kemppinen for assistance with the report on Finland. Maura Capoulas Santos and Alberto Galhardo Simões from Miranda Correia Amendoeira & Associados for assistance with the report on Portugal. Gustaf Reuterskiöld and Malin Cope from DLA Nordic for assistance with the report on Sweden. Infra-News for assistance generally and in particular with the project lists. All those members of DLA Piper who assisted with the preparation of the country reports and finally, Rosemary Bointon, Editor of the Report. Production of Report and Copyright This European PPP Report 2009 ( “Report”) has been produced and edited by DLA Piper*. DLA Piper acknowledges the contribution of the European PPP Expertise Centre (EPEC)** in the preparation of the Report. DLA Piper retains editorial responsibility for the Report. In contributing to the Report neither the European Investment Bank, EPEC, EPEC’s Members, nor any Contributor*** indicates or implies agreement with, or endorsement of, any part of the Report. This document is the copyright of DLA Piper and the Contributors. This document is confidential and personal to you. It is provided to you on the understanding that it is not to be re-used in any way, duplicated or distributed without the written consent of DLA Piper or the relevant Contributor. -

Final Exploitation Plan

D9.10 – Final Exploitation Plan Jorge Lpez (Atos), Alessandra Tedeschi (DBL), Julian Williams (UDUR), abio Massacci (UNITN), Raminder Ruprai (NGRID), Andreas Schmitz ( raunhofer), Emilio Lpez (URJC), Michael Pellot (TMB), Zden,a Mansfeldov. (ISASCR), Jan J/r0ens ( raunhofer) Pending of approval from the Research Executive Agency - EC Document Number D1.10 Document Title inal e5ploitation plan Version 1.0 Status inal Work Packa e WP 1 Deliverable Type Report Contractual Date of Delivery 31 .01 .20 18 Actual Date of Delivery 31.01.2018 Responsible Unit ATOS Contributors ISASCR, UNIDUR, UNITN, NGRID, DBL, URJC, raunhofer, TMB (eyword List E5ploitation, ramewor,, Preliminary, Requirements, Policy papers, Models, Methodologies, Templates, Tools, Individual plans, IPR Dissemination level PU SECONO.ICS Consortium SECONOMICS ?Socio-Economics meets SecurityA (Contract No. 28C223) is a Collaborative pro0ect) within the 7th ramewor, Programme, theme SEC-2011.E.8-1 SEC-2011.7.C-2 ICT. The consortium members are: UniversitG Degli Studi di Trento (UNITN) Pro0ect Manager: prof. abio Massacci 1 38100 Trento, Italy abio.MassacciHunitn.it www.unitn.it DEEP BLUE Srl (DBL) Contact: Alessandra Tedeschi 2 00113 Roma, Italy Alessandra.tedeschiHdblue.it www.dblue.it raunhofer -Gesellschaft zur Irderung der angewandten Contact: Prof. Jan J/r0ens 3 orschung e.V., Hansastr. 27c, 0an.0uer0ensHisst.fraunhofer.de 80E8E Munich, Germany http://www.fraunhofer.de/ UNIVERSIDAD REL JUAN CARLOS, Contact: Prof. David Rios Insua 8 Calle TulipanS/N, 28133, Mostoles david.riosHur0c.es -

Freezing in Naples Underground

THE ARTIFICIAL GROUND FREEZING TECHNIQUE APPLICATION FOR THE NAPLES UNDERGROUND Giuseppe Colombo a Construction Supervisor of Naples underground, MM c Technicalb Director MM S.p.A., via del Vecchio Polit Abstract e Technicald DirectorStudio Icotekne, di progettazione Vico II S. Nicola Lunardi, all piazza S. Marco 1, The extension of the Naples Technical underground Director between Rocksoil Pia S.p.A., piazza S. Marc Direzionale by using bored tunnelling methods through the Neapo Cassania to unusually high heads of water for projects of th , Pietro Lunardi natural water table. Given the extreme difficulty of injecting the mater problem of waterproofing it during construction was by employing artificial ground freezing (office (AGF) district) metho on Line 1 includes 5 stations. T The main characteristics of this ground treatment a d with the main problems and solutions adopted during , Vittorio Manassero aspects of this experience which constitutes one of Italy, of the application of AGF technology. b , Bruno Cavagna e c S.p.A., Naples, Giovanna e a Dogana 9,ecnico Naples 8, Milan ion azi Sta o led To is type due to the presence of the Milan zza Dante and the o 1, Milan ial surrounding thelitan excavation, yellow tuff, the were subject he stations, driven partly St taz Stazione M zio solved for four of the stations un n Università ic e ds. ip Sta io zione Du e omo re presented in the text along the major the project examples, and theat leastsignificant in S t G ta a z r io iibb n a e Centro lldd i - 1 - 1. -

Albo-AEC-PIETRANGELI-18-02-2019

Associazione Europea Ferrovieri – Italia ALBO DELLE ASSOCIAZIONI FERROVIARIE E CULTURALI DELL’AREA DELLE FERROVIE TURISTICHE a cura di: Mario Pietrangeli Con il patrocinio di: _____________________________________________________________________________ Pubblicazione prodotta sotto l’egida della: Edizione: febbraio 2019 2 PREFAZIONE Il 16 settembre 2017 si costituisce a Pesaro – nell’ambito delle iniziative degli Stati Generali della Mobilità Nuova - l’Alleanza per la Mobilità Dolce. Essa nasce dal desiderio delle più importanti Associazioni Nazionali, impegnate sul tema, di collaborare per promuovere e far crescere la mobilità dolce, attraverso una serie di azioni e attività da sviluppare congiuntamente. La rete sul territorio per la mobilita dolce promuove il piacere del viaggio a bassa velocità e la mobilità attiva, integrando percorsi ciclabili, reti di cammini, ferrovie turistiche, linee ferroviarie locali, riutilizzando e qualificando il patrimonio esistente, in una visione integrata con il trasporto collettivo: una rete dolce, semplice da utilizzare da parte di tutti. Obiettivo principale è la promozione, di una Rete Nazionale (nel futuro si pensa di estendere tale promozione anche a livello Europeo) di Mobilità Dolce e Sostenibile (Integrata con le realtà Turistiche, Artistiche, Gastronomiche delle Località e dei Piccoli Borghi Attraversati) che abbia come requisiti fondamentali: il recupero delle infrastrutture territoriali dismesse (ferrovie, infrastrutture ferroviarie, funivie, canali e vie fluviali, strade arginali, percorsi -

Particulate Matter Concentrations in a New Section of Metro Line: a Case Study in Italy

Computers in Railways XIV 523 Particulate Matter concentrations in a new section of metro line: a case study in Italy A. Cartenì1 & S. Campana2 1Department of Civil, Construction and Environmental Engineering, University of Naples Federico II, Italy 2Department of Industrial Engineering and Information, Second University of Naples, Italy Abstract All round the world, many studies have measured elevated concentrations of Particulate Matter (PM) in underground metro systems, with non-negligible implications for human health due to protracted exposition to fine particles. Starting from this consideration, the aim of this research was to investigate what is the “aging time” needed to measure high PM concentrations also in new stations of an underground metro line. This was possible taking advantage of the opening, in December 2013, of a new section of the Naples (Italy) line 1 railways. The Naples underground metro line 1 before December 31 was long – about 13 km with 14 stations. The new section, opened in December, consists of 5 new kilometres of line and 3 new stations. During the period December 2013– January 2014, an extensive sampling survey was conducted to measure PM10 concentrations both in the “historical” stations and in the “new” ones. The results of the study are twofold: a) the PM10 concentrations measured in the historical stations confirm the average values of literature; b) just a few days after the opening of the new metro section, high PM10 concentrations were also measured in the new stations with average PM10 values comparable (from a statistical point of view) with those measured in the historical stations of the line. -

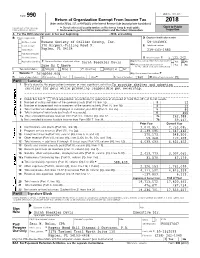

Humane Society Return

OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax 2018 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundations) Open to Public Department of the Treasury G Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Internal Revenue Service G Go to www.irs.gov/Form990 for instructions and the latest information. Inspection A For the 2018 calendar year, or tax year beginning , 2018, and ending , B Check if applicable: C D Employer identification number Address change Humane Society of Collier County, Inc. 59-1033966 Name change 370 Airport-Pulling Road N. E Telephone number Initial return Naples, FL 34104 239-643-1880 Final return/terminated Amended return G Gross receipts $ 5,122,242. Is this a group return for subordinates? Application pending F Name and address of principal officer: Sarah Baeckler Davis H(a) Yes X No H(b) Are all subordinates included? Yes No Same As C Above If "No," attach a list. (see instructions) I Tax-exempt status: X 501(c)(3) 501(c) ()H (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 J Website: G hsnaples.org H(c) Group exemption number G K Form of organization: X Corporation Trust Association OtherG L Year of formation: 1960 M State of legal domicile: FL Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities:To provide shelter and adoption services for pets while promoting responsible pet ownership. 2 Check this box G if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets. -

Naples Photo: Freeday/Shutterstock.Com Meet Naples, the City Where History and Culture Are Intertwined with Flavours and Exciting Activities

Naples Photo: Freeday/Shutterstock.com Meet Naples, the city where history and culture are intertwined with flavours and exciting activities. Explore the cemetery of skulls within the Fontanelle cemetery and the lost city of Pompeii, or visit the famous Vesuvius volcano and the island of Capri. Discover the lost tunnels of Naples and discover the other side of Naples, then end the day visiting the bars, restaurants and vivid nightlife in the evening. Castles, museums and churches add a finishing touch to the picturesque old-world feel. S-F/Shutterstock.com Top 5 Museum of Capodimonte The castle of Capodimonte boasts a wonderful view on the Bay of Naples. Buil... Castel Nuovo Also known as 'Maschio Angioino', this medieval castle dating back to 1279 w... Ovo Castle canadastock/Shutterstock.com Literally named 'Egg Castle', Castel dell'Ovo is a 12th-century fortress tha... Basilica of Saint Clare Not far from Church of Gesù Nuovo, the Basilica of Saint Clare is the bigges... Church of San Lorenzo Maggiore San Lorenzo Maggiore is an extraordinary building complex which mixes gothic... marcovarro/Shutterstock.com Updated 11 December 2019 Destination: Naples Publishing date: 2019-12-11 THE CITY is marked by contrasts and popular traditions, such as the annual miracle whereby San Gennaro’s ‘blood’ becomes liquid in front of the eyes of his followers. Naples is famous throughout the world primarly because of pizza (which, you'll discover, only constitutes a small part of the rich local cuisine) and popular music, with famous songs such as 'O Sole Mio'. canadastock/Shutterstock.com Museum of Capodimonte The historic city of Naples was founded about The castle of 3,000 years ago as Partenope by Greek Capodimonte boasts a merchants.