Season 2010 Season 2010-2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ESSENTIAL Yan Pascal Tortelier

CHAN 241-32 THE ESSENTIAL Margaret Fingerhut piano Ulster Orchestra • BBC Philharmonic 32 Yan Pascal Tortelier 33 CCHANHAN 2241-3241-32 BBook.inddook.indd 332-332-33 222/8/062/8/06 110:27:030:27:03 Paul Dukas (1865 –1935) COMPACT DISC ONE 1 Fanfare pour précéder ‘La Péri’ * 1:55 2 La Péri * 17:40 Poème dansé en un tableau 3 Lipnitzki / Lebrecht Music & Arts Lipnitzki / Lebrecht Photo Library L’Apprenti sorcier * 11: 31 Scherzo d’après une ballade de Goethe Symphony in C major † 41: 00 in C-Dur • en ut majeur 4 I Allegro non troppo vivace, ma con fuoco 14:41 5 II Andante espressivo e sostenuto 14:51 6 III Allegro spiritoso 11:18 TT 72:21 COMPACT DISC TWO 1 Polyeucte † 15:03 Overture after Corneille Andante sostenuto – Allegro non troppo vivace – Andante espressivo – Mouvement du 1er allegro – Andante sostenuto Paul Dukas 3 CCHANHAN 2241-3241-32 BBook.inddook.indd 22-3-3 222/8/062/8/06 110:26:530:26:53 The Essential Paul Dukas Sonate ‡ 47:43 ‘A good provision of sunlight’: this was in the rigid Conservatoire mould? Dukas’s in E minor • in e-Moll • en mi mineur how one nineteenth-century French critic offi cial advice to young conductors betrayed 2 I Modérément vif – expressif et marqué 12:04 described the ‘compositional palette’ of not a shred of poetry: 3 II Calme – un peu lent – très soutenu 12:49 Emmanuel Chabrier, and that vivid double There is only one secret in conducting an imagery of light and colour recurs throughout orchestra: the right hand should be raised, 4 III Vivement, avec légèreté 8:38 much writing on French music of the period. -

Repertoire List

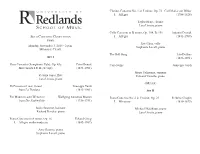

APPROVED REPERTOIRE FOR 2022 COMPETITION: Please choose your repertoire from the approved selections below. Repertoire substitution requests will be considered by the Charlotte Symphony on an individual case-by-case basis. The deadline for all repertoire approvals is September 15, 2021. Please email [email protected] with any questions. VIOLIN VIOLINCELLO J.S. BACH Violin Concerto No. 1 in A Minor BOCCHERINI All cello concerti Violin Concerto No. 2 in E Major DVORAK Cello Concerto in B Minor BEETHOVEN Romance No. 1 in G Major Romance No. 2 in F Major HAYDN Cello Concerto No. 1 in C Major Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Major BRUCH Violin Concerto No. 1 in G Minor LALO Cello Concerto in D Minor HAYDN Violin Concerto in C Major Violin Concerto in G Major SAINT-SAENS Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Cello Concerto No. 2 in D Minor LALO Symphonie Espagnole for Violin SCHUMANN Cello Concerto in A Minor MENDELSSOHN Violin Concerto in E Minor DOUBLE BASS MONTI Czárdás BOTTESINI Double Bass Concerto No. 2in B Minor MOZART Violin Concerti Nos. 1 – 5 DITTERSDORF Double Bass Concerto in E Major PROKOFIEV Violin Concerto No. 2 in G Minor DRAGONETTI All double bass concerti SAINT-SAENS Introduction & Rondo Capriccioso KOUSSEVITSKY Double Bass Concerto in F# Minor Violin Concerto No. 3 in B Minor HARP SCHUBERT Rondo in A Major for Violin and Strings DEBUSSY Danses Sacrée et Profane (in entirety) SIBELIUS Violin Concerto in D Minor DITTERSDORF Harp Concerto in A Major VIVALDI The Four Seasons HANDEL Harp Concerto in Bb Major, Op. -

Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op

Clarinet Concerto No. 1 in F minor, Op. 73 Carl Maria von Weber I. Allegro (1786-1826) Taylor Heap, clarinet Lara Urrutia, piano Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. 104, B. 191 Antonin Dvorák SOLO CONCERTO COMPETITION I. Allegro (1841-1904) Finals Xue Chen, cello Monday, November 3, 2014 - 2 p.m. Stephanie Lovell, piano MEMORIAL CHAPEL The Bell Song Léo Delibes SET I (1836-1891) Flute Concerto (Symphonic Tale), Op. 43a Peter Benoit Caro Nome Guiseppe Verdi Movements I & II (excerpt) (1834-1901) Mayu Uchiyama, soprano Victoria Jones, flute Edward Yarnelle, piano Lara Urrutia, piano - BREAK - Di Provenza il mar, il suol Giuseppe Verdi from La Traviata (1813-1901) SET II Ein Madehen oder Weibchen Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21 Frédéric Chopin from Die Zauberflöte (1756-1791) I. Maestoso (1810-1849) Justin Brunette, baritone Michael Malakouti, piano Richard Bentley, piano Lara Urrutia, piano Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 16 Edvard Grieg I. Allegro molto moderato (1843-1907) Amy Rooney, piano Stephanie Lovell, piano Que fais-tu, blanche tourterelle Charles Gounod ABOUT THE CONCERTO COMPETITION from Roméo et Juliette (1818-1893) Beginning in 1976, the Concerto Competition has become an annual event Cruda Sorte Gioacchino Rossini for the University of Redlands School of Music and its students. Music from L’Ataliana in Algeri (1792-1868) students compete for the coveted prize of performing as soloist with the Redlands Symphony Orchestra, the University Orchestra or the Wind Jordan Otis, soprano Ensemble. Twyla Meyer, piano This year the Preliminary Rounds of the Competition took place on Friday, October 31st and Saturday, November 1st. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’

‘The Art-Twins of Our Timestretch’: Percy Grainger, Frederick Delius and the 1914–1934 American ‘Delius Campaign’ Catherine Sarah Kirby Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Music (Musicology) April 2015 Melbourne Conservatorium of Music The University of Melbourne Produced on archival quality paper Abstract This thesis explores Percy Grainger’s promotion of the music of Frederick Delius in the United States of America between his arrival in New York in 1914 and Delius’s death in 1934. Grainger’s ‘Delius campaign’—the title he gave to his work on behalf of Delius— involved lectures, articles, interviews and performances as both a pianist and conductor. Through this, Grainger was responsible for a number of noteworthy American Delius premieres. He also helped to disseminate Delius’s music by his work as a teacher, and through contact with publishers, conductors and the press. In this thesis I will examine this campaign and the critical reception of its resulting performances, and question the extent to which Grainger’s tireless promotion affected the reception of Delius’s music in the USA. To give context to this campaign, Chapter One outlines the relationship, both personal and compositional, between Delius and Grainger. This is done through analysis of their correspondence, as well as much of Grainger’s broader and autobiographical writings. This chapter also considers the relationship between Grainger, Delius and others musicians within their circle, and explores the extent of their influence upon each other. Chapter Two examines in detail the many elements that made up the ‘Delius campaign’. -

DELIUS BOOKLET:Bob.Qxd 14/4/08 16:09 Page 1

DELIUS BOOKLET:bob.qxd 14/4/08 16:09 Page 1 second piece, Summer Night on the River, is equally evocative, this time suggested by the river Loing that lay at the the story of a voodoo prince sold into slavery, based on an episode in the novel The Grandissimes by the American bottom of Delius’s garden near Fontainebleau, the kind of scene that might have been painted by some of the French writer George Washington Cable. The wedding dance La Calinda was originally a dance of some violence, leading to painters that were his contemporaries. hysteria and therefore banned. In the Florida Suite and again in Koanga it lacks anything of its original character. The opera Irmelin, written between 1890 and 1892, and the first attempt by Delius at the form, had no staged Koanga, a lyric drama in a prologue and three acts, was first heard in an incomplete concert performance at St performance until 1953, when Beecham arranged its production in Oxford. The libretto, by Delius himself, deals with James’s Hall in 1899. It was first staged at Elberfeld in 1904. With a libretto by Delius and Charles F. Keary, the plot The Best of two elements, Princess Irmelin and her suitors, none of whom please her, and the swine-herd who eventually wins is set on an eighteenth century Louisiana plantation, where the slave-girl Palmyra is the object of the attentions of her heart. The Prelude, designed as an entr’acte for the later opera Koanga, makes use of four themes from Irmelin. -

28Apr2004p2.Pdf

144 NAXOS CATALOGUE 2004 | ALPHORN – BAROQUE ○○○○ ■ COLLECTIONS INVITATION TO THE DANCE Adam: Giselle (Acts I & II) • Delibes: Lakmé (Airs de ✦ ✦ danse) • Gounod: Faust • Ponchielli: La Gioconda ALPHORN (Dance of the Hours) • Weber: Invitation to the Dance ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Slovak RSO / Ondrej Lenárd . 8.550081 ■ ALPHORN CONCERTOS Daetwyler: Concerto for Alphorn and Orchestra • ■ RUSSIAN BALLET FAVOURITES Dialogue avec la nature for Alphorn, Piccolo and Glazunov: Raymonda (Grande valse–Pizzicato–Reprise Orchestra • Farkas: Concertino Rustico • L. Mozart: de la valse / Prélude et La Romanesca / Scène mimique / Sinfonia Pastorella Grand adagio / Grand pas espagnol) • Glière: The Red Jozsef Molnar, Alphorn / Capella Istropolitana / Slovak PO / Poppy (Coolies’ Dance / Phoenix–Adagio / Dance of the Urs Schneider . 8.555978 Chinese Women / Russian Sailors’ Dance) Khachaturian: Gayne (Sabre Dance) • Masquerade ✦ AMERICAN CLASSICS ✦ (Waltz) • Spartacus (Adagio of Spartacus and Phrygia) Prokofiev: Romeo and Juliet (Morning Dance / Masks / # DREAMER Dance of the Knights / Gavotte / Balcony Scene / A Portrait of Langston Hughes Romeo’s Variation / Love Dance / Act II Finale) Berger: Four Songs of Langston Hughes: Carolina Cabin Shostakovich: Age of Gold (Polka) •␣ Bonds: The Negro Speaks of Rivers • Three Dream Various artists . 8.554063 Portraits: Minstrel Man •␣ Burleigh: Lovely, Dark and Lonely One •␣ Davison: Fields of Wonder: In Time of ✦ ✦ Silver Rain •␣ Gordon: Genius Child: My People • BAROQUE Hughes: Evil • Madam and the Census Taker • My ■ BAROQUE FAVOURITES People • Negro • Sunday Morning Prophecy • Still Here J.S. Bach: ‘In dulci jubilo’, BWV 729 • ‘Nun komm, der •␣ Sylvester's Dying Bed • The Weary Blues •␣ Musto: Heiden Heiland’, BWV 659 • ‘O Haupt voll Blut und Shadow of the Blues: Island & Litany •␣ Owens: Heart on Wunden’ • Pastorale, BWV 590 • ‘Wachet auf’ (Cantata, the Wall: Heart •␣ Price: Song to the Dark Virgin BWV 140, No. -

A Study of Tyzen Hsiao's Piano Concerto, Op. 53

A Study of Tyzen Hsiao’s Piano Concerto, Op. 53: A Comparison with Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concerto No. 2 D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lin-Min Chang, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2018 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Steven Glaser, Advisor Dr. Anna Gowboy Dr. Kia-Hui Tan Copyright by Lin-Min Chang 2018 2 ABSTRACT One of the most prominent Taiwanese composers, Tyzen Hsiao, is known as the “Sergei Rachmaninoff of Taiwan.” The primary purpose of this document is to compare and discuss his Piano Concerto Op. 53, from a performer’s perspective, with the Second Piano Concerto of Sergei Rachmaninoff. Hsiao’s preferences of musical materials such as harmony, texture, and rhythmic patterns are influenced by Romantic, Impressionist, and 20th century musicians incorporating these elements together with Taiwanese folk song into a unique musical style. This document consists of four chapters. The first chapter introduces Hsiao’s biography and his musical style; the second chapter focuses on analyzing Hsiao’s Piano Concerto Op. 53 in C minor from a performer’s perspective; the third chapter is a comparison of Hsiao and Rachmaninoff’s Piano Concertos regarding the similarities of orchestration and structure, rhythm and technique, phrasing and articulation, harmony and texture. The chapter also covers the differences in the function of the cadenza, and the interaction between solo piano and orchestra; and the final chapter provides some performance suggestions to the practical issues in regard to phrasing, voicing, technique, color, pedaling, and articulation of Hsiao’s Piano Concerto from the perspective of a pianist. -

12 August 2021

12 August 2021 12:01 AM Franz Berwald (1796-1868) Fantasia on 2 Swedish Folksongs for piano (1850-59) Lucia Negro (piano) SESR 12:10 AM Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) Intermezzo (excerpt from 'Manon Lescaut' between Acts 2 and 3) BBC Philharmonic, Gianandrea Noseda (conductor) GBBBC 12:15 AM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 - 1827) Romance in F major Op 50 (orig. for violin and orchestra) Taik-Ju Lee (violin), Young-Lan Han (piano) KRKBS 12:25 AM Richard Wagner (1813-1883), Mathilde Wesendonck (author) Wesendonck-Lieder for voice and orchestra Jane Eaglen (soprano), Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra, Juanjo Mena (conductor) NONRK 12:47 AM Marin Marais (1656-1728) Les Folies d'Espagne Lise Daoust (flute) CACBC 12:57 AM Anonymous Yo me soy la morenica Olga Pitarch (soprano), Accentus Austria, Thomas Wimmer (director) DEWDR 01:00 AM Joseph Bologne Chevalier de Saint-Georges (1745-1799) Violin Concerto in D major (Op 3 no 1) (1774) Linda Melsted (violin), Tafelmusik Orchestra, Jeanne Lamon (conductor) CACBC 01:22 AM Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) 6 Impromptus, Op 5 Juhani Lagerspetz (piano) FIYLE 01:38 AM Heikki Suolahti (1920-1936) Sinfonia Piccola (1935) Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Kari Tikka (conductor) FIYLE 02:01 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Overture to The Marriage of Figaro, K.492 Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Patrik Ringborg (conductor) SESR 02:05 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791), Lorenzo Da Ponte (librettist) 'Dove sono i bei momenti' - Countess' aria from The Marriage of Figaro. K.492 Christina Nilsson (soprano), Swedish -

Gianandrea Noseda CHAN 10298 BOOK.Qxd 14/9/06 2:16 Pm Page 2

CHAN 10298 Booklet cover 9/13/05 12:19 PM Page 1 CHAN 10298 CHANDOS Returning Waves A Sorrowful Tale Episode at a Masquerade BBC Philharmonic Gianandrea Noseda CHAN 10298 BOOK.qxd 14/9/06 2:16 pm Page 2 Mieczysl/aw Karl/owicz (1876–1909) Returning Waves, Op. 9 24:00 Symphonic poem 1 Andante – 4:25 2 [Andante] – 2:02 3 Andante assai – 5:36 4 Andantino – 6:35 5 Andante 5:22 6 A Sorrowful Tale, Op. 13 10:19 (Preludes to Eternity) Lento lugubre – Moderato assai – Tempo I – Moderato giocoso – Tempo I Episode at a Masquerade, Op. 14 25:00 Symphonic poem 7 Allegro maestoso – Molto agitato – A tempo – Andante – 6:52 8 Molto lento – 7:54 9 Andante – 1:47 10 Allegro maestoso – Molto agitato – Molto largamente – 3:47 11 Molto lento 4:39 TT 59:39 BBC Philharmonic Yuri Torchinsky leader Gianandrea Noseda Mieczyslaw⁄ Karlowicz⁄ 3 CHAN 10298 BOOK.qxd 14/9/06 2:16 pm Page 4 by step, while the work’s tonal scheme revolves subtitle – Preludes to Eternity – hint at the Karl/owicz: Returning Waves and other works almost entirely around mediant relationships. consolation of Nirvana already expressed in The main sections are linked by transitional Eternal Songs. Uncharacteristically, Karlowicz⁄ material featuring a fanfare, initially on trumpet, initially wished to introduce a gunshot at the The Polish composer Mieczyslaw⁄ Karlowicz⁄ his torpor as he gazed at ‘lifeless ice crystals which clearly denotes the onset of the climax. In fact, as early as the second (1876–1909) finished the first of his six on the window pane’, coincidentally an image subject’s recollections. -

R Obert Schum Ann's Piano Concerto in AM Inor, Op. 54

Order Number 0S0T795 Robert Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A Minor, op. 54: A stemmatic analysis of the sources Kang, Mahn-Hee, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1992 U MI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 ROBERT SCHUMANN S PIANO CONCERTO IN A MINOR, OP. 54: A STEMMATIC ANALYSIS OF THE SOURCES DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Mahn-Hee Kang, B.M., M.M., M.M. The Ohio State University 1992 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Lois Rosow Charles Atkinson - Adviser Burdette Green School of Music Copyright by Mahn-Hee Kang 1992 In Memory of Malcolm Frager (1935-1991) 11 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the late Malcolm Frager, who not only enthusiastically encouraged me In my research but also gave me access to source materials that were otherwise unavailable or hard to find. He gave me an original exemplar of Carl Relnecke's edition of the concerto, and provided me with photocopies of Schumann's autograph manuscript, the wind parts from the first printed edition, and Clara Schumann's "Instructive edition." Mr. Frager. who was the first to publish information on the textual content of the autograph manuscript, made It possible for me to use his discoveries as a foundation for further research. I am deeply grateful to him for giving me this opportunity. I express sincere appreciation to my adviser Dr. Lois Rosow for her patience, understanding, guidance, and insight throughout the research. -

Gianandrea Noseda, Conductor the Recording Activity

Gianandrea Noseda, conductor The recording activity Enric Granados (1867 - 1916) Goyescas (Opera in three tableaux) Orquesta de Cadaques / Coral de Bilbao TRITO’, 1997 Aria - The Opera Album Andrea Bocelli, Orchestra of the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino PHILIPS, 1998 Ottorino Respighi (1879-1936) La Boutique fantasque, P 120, La pentola magica, P 129, Prelude and Fugue, P 158 BBC Philharmonic CHANDOS, 2002 Xavier Montsalvatge (1912-2002) Tribute to Montsalvatge (Sortilegi – Sinfonietta-concerto - Metamorfosi de concert) Orquesta de Cadaques TRITO’, 2002 Anna Netrebko - Opera Arias Wiener Staatsopernchor / Wiener Philharmoniker DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON, 2003 Sergey Prokofiev (1891-1953) The Tale of the Stone Flower, Op. 118 (Complete ballet) – 2 CD BBC Philharmonic CHANDOS, 2003 Mieczyslaw Karlowicz (1876-1909) Bianca da Molena, Serenade for String Orchestra, Op. 2, 'Rebirth' Symphony, Op. 7 BBC Philharmonic CHANDOS, 2003 Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Sinfonia n. 9 in do magg. «La Grande» D 944, Ouverture in mi min. D 648 BBC Philharmonic PARAGON, 2004 Luigi Dallapiccola (1904-1975) Tartiniana (1951) – Due Pezzi (1947) – Piccola musica notturna (1954) - Frammenti Sinfonici dal Balletto 'Marsia' (1942-43; 1947) - Variazioni per Orchestra (1953-54) James Ehnes violin* / BBC Philharmonic CHANDOS, 2004 Antonín Dvorak (1841-1904) Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 33 (B 63) (1876)* - Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 53 (B 96) James Ehnes violin / Rustem Hayroudinoff piano / BBC Philharmonic CHANDOS, 2004 Franz Liszt (1811-1886) Symphonic Poems, Volume 1 / Ce qu'on entend sur la montagne, S 95 - Tasso: Lamento e Trionfo, S 96 - Les Preludes, S 97 - Orpheus, S 98 BBC Philharmonic CHANDOS, 2004 Mieczyslaw Karlowicz (1876-1909) Returning Waves, Op.