Understanding the Zhejiang Industrial Clusters:Questions and Re-Evaluations Lu Shi, Bernard Ganne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ningbo Facts

World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Climate Resilient Ningbo Project Local Resilience Action Plan 213730-00 Final | June 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 213730-00 | Draft 1 | 16 June 2011 110630_FINAL REPORT.DOCX World Bank Climate Resilient Ningbo Project Local Resilience Action Plan Contents Page 1 Executive Summary 4 2 Introduction 10 3 Urban Resilience Methodology 13 3.1 Overview 13 3.2 Approach 14 3.3 Hazard Assessment 14 3.4 City Vulnerability Assessment 15 3.5 Spatial Assessment 17 3.6 Stakeholder Engagement 17 3.7 Local Resilience Action Plan 18 4 Ningbo Hazard Assessment 19 4.1 Hazard Map 19 4.2 Temperature 21 4.3 Precipitation 27 4.4 Droughts 31 4.5 Heat Waves 32 4.6 Tropical Cyclones 33 4.7 Floods 35 4.8 Sea Level Rise 37 4.9 Ningbo Hazard Analysis Summary 42 5 Ningbo Vulnerability Assessment 45 5.1 People 45 5.2 Infrastructure 55 5.3 Economy 69 5.4 Environment 75 5.5 Government 80 6 Gap Analysis 87 6.1 Overview 87 6.2 Natural Disaster Inventory 87 6.3 Policy and Program Inventory 89 6.4 Summary 96 7 Recommendations 97 7.1 Overview 97 7.2 People 103 7.3 Infrastructure 106 213730-00 | Draft 1 | 16 June 2011 110630_FINAL REPORT.DOCX World Bank Climate Resilient Ningbo Project Local Resilience Action Plan 7.4 Economy 112 7.5 Environment 115 7.6 Government 118 7.7 Prioritized Recommendations 122 8 Conclusions 126 213730-00 | Draft 1 | 16 June 2011 110630_FINAL REPORT.DOCX World Bank Climate Resilient Ningbo Project Local Resilience Action Plan List of Tables Table -

Appendix 1: Rank of China's 338 Prefecture-Level Cities

Appendix 1: Rank of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities © The Author(s) 2018 149 Y. Zheng, K. Deng, State Failure and Distorted Urbanisation in Post-Mao’s China, 1993–2012, Palgrave Studies in Economic History, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-92168-6 150 First-tier cities (4) Beijing Shanghai Guangzhou Shenzhen First-tier cities-to-be (15) Chengdu Hangzhou Wuhan Nanjing Chongqing Tianjin Suzhou苏州 Appendix Rank 1: of China’s 338 Prefecture-Level Cities Xi’an Changsha Shenyang Qingdao Zhengzhou Dalian Dongguan Ningbo Second-tier cities (30) Xiamen Fuzhou福州 Wuxi Hefei Kunming Harbin Jinan Foshan Changchun Wenzhou Shijiazhuang Nanning Changzhou Quanzhou Nanchang Guiyang Taiyuan Jinhua Zhuhai Huizhou Xuzhou Yantai Jiaxing Nantong Urumqi Shaoxing Zhongshan Taizhou Lanzhou Haikou Third-tier cities (70) Weifang Baoding Zhenjiang Yangzhou Guilin Tangshan Sanya Huhehot Langfang Luoyang Weihai Yangcheng Linyi Jiangmen Taizhou Zhangzhou Handan Jining Wuhu Zibo Yinchuan Liuzhou Mianyang Zhanjiang Anshan Huzhou Shantou Nanping Ganzhou Daqing Yichang Baotou Xianyang Qinhuangdao Lianyungang Zhuzhou Putian Jilin Huai’an Zhaoqing Ningde Hengyang Dandong Lijiang Jieyang Sanming Zhoushan Xiaogan Qiqihar Jiujiang Longyan Cangzhou Fushun Xiangyang Shangrao Yingkou Bengbu Lishui Yueyang Qingyuan Jingzhou Taian Quzhou Panjin Dongying Nanyang Ma’anshan Nanchong Xining Yanbian prefecture Fourth-tier cities (90) Leshan Xiangtan Zunyi Suqian Xinxiang Xinyang Chuzhou Jinzhou Chaozhou Huanggang Kaifeng Deyang Dezhou Meizhou Ordos Xingtai Maoming Jingdezhen Shaoguan -

Prohibited Agreements with Huawei, ZTE Corp, Hytera, Hangzhou Hikvision, Dahua and Their Subsidiaries and Affiliates

Prohibited Agreements with Huawei, ZTE Corp, Hytera, Hangzhou Hikvision, Dahua and their Subsidiaries and Affiliates. Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), 2 CFR 200.216, prohibits agreements for certain telecommunications and video surveillance services or equipment from the following companies as a substantial or essential component of any system or as critical technology as part of any system. • Huawei Technologies Company; • ZTE Corporation; • Hytera Communications Corporation; • Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology Company; • Dahua Technology company; or • their subsidiaries or affiliates, Entering into agreements with these companies, their subsidiaries or affiliates (listed below) for telecommunications equipment and/or services is prohibited, as doing so could place the university at risk of losing federal grants and contracts. Identified subsidiaries/affiliates of Huawei Technologies Company Source: Business databases, Huawei Investment & Holding Co., Ltd., 2017 Annual Report • Amartus, SDN Software Technology and Team • Beijing Huawei Digital Technologies, Co. Ltd. • Caliopa NV • Centre for Integrated Photonics Ltd. • Chinasoft International Technology Services Ltd. • FutureWei Technologies, Inc. • HexaTier Ltd. • HiSilicon Optoelectronics Co., Ltd. • Huawei Device Co., Ltd. • Huawei Device (Dongguan) Co., Ltd. • Huawei Device (Hong Kong) Co., Ltd. • Huawei Enterprise USA, Inc. • Huawei Global Finance (UK) Ltd. • Huawei International Co. Ltd. • Huawei Machine Co., Ltd. • Huawei Marine • Huawei North America • Huawei Software Technologies, Co., Ltd. • Huawei Symantec Technologies Co., Ltd. • Huawei Tech Investment Co., Ltd. • Huawei Technical Service Co. Ltd. • Huawei Technologies Cooperative U.A. • Huawei Technologies Germany GmbH • Huawei Technologies Japan K.K. • Huawei Technologies South Africa Pty Ltd. • Huawei Technologies (Thailand) Co. • iSoftStone Technology Service Co., Ltd. • JV “Broadband Solutions” LLC • M4S N.V. • Proven Honor Capital Limited • PT Huawei Tech Investment • Shanghai Huawei Technologies Co., Ltd. -

Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, Zhejiang Province, China

Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2510.181699 Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Zhejiang Province, China Appendix Appendix Table. Surveillance for carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in hospitals, Zhejiang Province, China, 2015– 2017* Years Hospitals by city Level† Strain identification method‡ excluded§ Hangzhou First 17 People's Liberation Army Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Red Cross Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou First People’s Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Hangzhou Children's Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Hospital of Chinese Traditional Hospital 3A Phoenix 100, VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Cancer Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Xixi Hospital of Hangzhou 3A VITEK 2 Compact Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University 3A MALDI-TOF MS The Children's Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine 3A MALDI-TOF MS Women's Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University 3A VITEK 2 Compact The First Affiliated Hospital of Medical School of Zhejiang University 3A MALDI-TOF MS The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of 3A MALDI-TOF MS Medicine Hangzhou Second People’s Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang People's Armed Police Corps Hospital, Hangzhou 3A Phoenix 100 Xinhua Hospital of Zhejiang Province 3A VITEK 2 Compact Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine 3A MALDI-TOF MS Tongde Hospital of Zhejiang Province 3A VITEK 2 Compact Zhejiang Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang Cancer -

A Survey of Marine Coastal Litters Around Zhoushan Island, China and Their Impacts

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article A Survey of Marine Coastal Litters around Zhoushan Island, China and Their Impacts Xuehua Ma 1, Yi Zhou 1, Luyi Yang 1 and Jianfeng Tong 1,2,3,* 1 College of Marine Science, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai 201306, China; [email protected] (X.M.); [email protected] (Y.Z.); [email protected] (L.Y.) 2 National Engineering Research Center for Oceanic Fisheries, Shanghai 201306, China 3 Experimental Teaching Demonstration Center for Marine Science and Technology, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai 201306, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Rapid development of the economy increased marine litter around Zhoushan Island. Social- ecological scenario studies can help to develop strategies to adapt to such change. To investigate the present situation of marine litter pollution, a stratified random sampling (StRS) method was applied to survey the distribution of marine coastal litters around Zhoushan Island. A univariate analysis of variance was conducted to access the amount of litter in different landforms that include mudflats, artificial and rocky beaches. In addition, two questionnaires were designed for local fishermen and tourists to provide social scenarios. The results showed that the distribution of litter in different landforms was significantly different, while the distribution of litter in different sampling points had no significant difference. The StRS survey showed to be a valuable method for giving a relative overview of beach litter around Zhoushan Island with less effort in a future survey. The questionnaire feedbacks helped to understand the source of marine litter and showed the impact on the local environment and economy. -

The Superfamily Calopterygoidea in South China: Taxonomy and Distribution. Progress Report for 2009 Surveys Zhang Haomiao* *PH D

International Dragonfly Fund - Report 26 (2010): 1-36 1 The Superfamily Calopterygoidea in South China: taxonomy and distribution. Progress Report for 2009 surveys Zhang Haomiao* *PH D student at the Department of Entomology, College of Natural Resources and Environment, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510642, China. Email: [email protected] Introduction Three families in the superfamily Calopterygoidea occur in China, viz. the Calo- pterygidae, Chlorocyphidae and Euphaeidae. They include numerous species that are distributed widely across South China, mainly in streams and upland running waters at moderate altitudes. To date, our knowledge of Chinese spe- cies has remained inadequate: the taxonomy of some genera is unresolved and no attempt has been made to map the distribution of the various species and genera. This project is therefore aimed at providing taxonomic (including on larval morphology), biological, and distributional information on the super- family in South China. In 2009, two series of surveys were conducted to Southwest China-Guizhou and Yunnan Provinces. The two provinces are characterized by karst limestone arranged in steep hills and intermontane basins. The climate is warm and the weather is frequently cloudy and rainy all year. This area is usually regarded as one of biodiversity “hotspot” in China (Xu & Wilkes, 2004). Many interesting species are recorded, the checklist and photos of these sur- veys are reported here. And the progress of the research on the superfamily Calopterygoidea is appended. Methods Odonata were recorded by the specimens collected and identified from pho- tographs. The working team includes only four people, the surveys to South- west China were completed by the author and the photographer, Mr. -

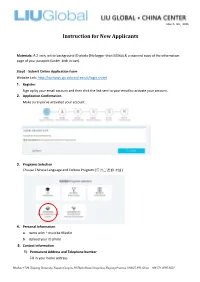

ZJU Instructions for New Applicants

March 5th, 2020 Instruction for New Applicants Materials: A 2-inch, white background ID photo (No bigger than 500kb) & a scanned copy of the information page of your passport (under 1mb in size). Step1 - Submit Online Application Form Website Link: http://isinfosys.zju.edu.cn/recruit/login.shtml 1. Register: Sign up by your email account and then click the link sent to your email to activate your account. 2. Application Confirmation Make sure you’ve activated your account. 3. Programs Selection Choose Chinese Language and Culture Program (汉语言进修项目). 4. Personal Information a. Items with * must be filled in b. Upload your ID photo 5. Contact Information 1) Permanent Address and Telephone Number Fill in your home address Mailbox 1709, Zhejiang University, Yuquan Campus, 38 Zheda Road, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province 310027, P.R. China +86 571 8795 2051 March 5th, 2020 2) Address to Receive Admission Documents & Telephone Number a. If you are in the States, please fill in your mailing address. (please fill in the English address, otherwise it will affect the accurate postal delivery.) b. If you are out of the States, please fill in the address of China Center. (Copy the information below) Country – China City - HangZhou Postal Code – 310027 Address – Room 303, Building 11, 38 Zheda Road, Zhejiang University Yuquan Campus, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, P.R. China 3) Current Contacts (Copy the information below) Mailbox 1709, Zhejiang University, Yuquan Campus, 38 Zheda Road, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province 310027, P.R. China +86 571 8795 2051 March 5th, 2020 Emergency Contact Person – Danyang (Ann) Zheng Emergency Contact Phone Number -13777886407 Emergency Contact Address - Room 303, Building 11, 38 Zheda Road, Zhejiang U niversity Yuquan Campus, Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, P.R. -

Tonatory Patterns in Taizhou Wu Tones

TONATORY PATTERNS IN TAIZHOU WU TONES Phil Rose Emeritus Faculty, Australian National University [email protected] ABSTRACT 台州 subgroup of Wu to which Huángyán belongs. The issue has significance within descriptive Recordings of speakers of the Táizhou subgroup of tonetics, tonatory typology and historical linguistics. Wu Chinese are used to acoustically document an Wu dialects – at least the conservative varieties – interaction between tone and phonation first attested show a wide range of tonatory behaviour [11]. One in 1928. One or two of their typically seven or eight finds breathy or ventricular phonation in groups of tones are shown to have what sounds like a mid- tones characterising natural tonal classes of Rhyme glottal-stop, thus demonstrating a new importance for phonotactics and Wu’s complex tone pattern in Wu tonatory typology. Possibly reflecting sandhi. One also finds a single tone characterised by gradual loss, larygealisation appears restricted to the a different non-modal phonation type [12]; or even north and north-west, and is absent in Huángyán two different non-modal phonation types in two dialect where it was first described. A perturbatory tones. However, the Huangyan-type tonation seems model of the larygealisation is tested in an to involve a new variation, with the same phonation experiment determining how much of the complete type in two different tones from the same historical tonal F0 contour can be restored from a few tonal category, thus prompting speculation that it centiseconds of modal F0 at Rhyme onset and offset. developed before the tonal split. The results are used both to acoustically quantify laryngealised tonal F0, with its problematic jitter and 2. -

New Constraints on Intraplate Orogeny in the South China Continent

Gondwana Research 24 (2013) 902–917 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Gondwana Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/gr Systematic variations in seismic velocity and reflection in the crust of Cathaysia: New constraints on intraplate orogeny in the South China continent Zhongjie Zhang a,⁎, Tao Xu a, Bing Zhao a, José Badal b a State Key Laboratory of Lithospheric Evolution, Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029, China b Physics of the Earth, Sciences B, University of Zaragoza, Pedro Cerbuna 12, 50009 Zaragoza, Spain article info abstract Article history: The South China continent has a Mesozoic intraplate orogeny in its interior and an oceanward younging in Received 16 December 2011 postorogenic magmatic activity. In order to determine the constraints afforded by deep structure on the for- Received in revised form 15 May 2012 mation of these characteristics, we reevaluate the distribution of crustal velocities and wide-angle seismic re- Accepted 18 May 2012 flections in a 400 km-long wide-angle seismic profile between Lianxian, near Hunan Province, and Gangkou Available online 18 June 2012 Island, near Guangzhou City, South China. The results demonstrate that to the east of the Chenzhou-Linwu Fault (CLF) (the southern segment of the Jiangshan–Shaoxing Fault), the thickness and average P-wave veloc- Keywords: Wide-angle seismic data ity both of the sedimentary layer and the crystalline basement display abrupt lateral variations, in contrast to Crustal velocity layering to the west of the fault. This suggests that the deformation is well developed in the whole of the crust Frequency filtering beneath the Cathaysia block, in agreement with seismic evidence on the eastwards migration of the orogeny Migration and stacking and the development of a vast magmatic province. -

Signify N.V. and Legal Entities with Respect to Which Signify N.V

Signify N.V. and legal entities with respect to which Signify N.V. directly or indirectly holds 50% or more of the nominal value of the issued share capital or ownership interest: Country Company Argentina Signify Argentina S.A. Australia Signify Australia Limited Australia Dynalite Pty. Limited Austria Signify Austria GmbH Bangladesh Signify Bangladesh Limited Belgium EMGO Belgium Signify Belgium N.V. Belgium PITS N.V. Belgium Signify Properties N.V. Belgium Sedena Financial Services BVBA Brazil Helfont Participações Ltda. Brazil Signify Iluminação Brasil Ltda. Brunei Darussalam Signify (B) Sdn Bhd Bulgaria Signify International B.V. – Bulgaria Branch Canada Signify Canada Holding Ltd. Canada Signify Canada Ltd. Chile Signify Chilena S.A. China Signify Energy Saving Technology Services (Wuhan) Co., Ltd. China Signify Industry (China) Co., Ltd. China Signify Electronics (Xiamen) Co. Ltd. China Signify Luminaires (Chengdu) Co., Ltd. China Signify Luminaires (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. China Carex Lighting Equipment (Dongguan) Co., Ltd. China Signify Electronics Technology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. China Signify (China) Investment Co., Ltd China Feihui Lighting Technology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. China Signify Trading (Shanghai) Co., Ltd China Shanghai Wei Shi Intelligent Lighting Co., Ltd. China Zhejiang Klite Holdings Co., Ltd. China Haining Klite International Trade Co., Ltd. China Ningbo Deming International Trade Co., Ltd. China Ningbo Klite Electric Manufacture Co., Ltd. China Ningbo Klite Lighting Electric Technology Co., Ltd. China Zhejiang Klite Lighting Holdings Co., Ltd. Shanghai Branch China Shenzhen Leifei Technologies Co., Ltd. China Foshan Leifei Technologies Co., Ltd. Colombia Signify Colombiana S.A.S. Croatia Signify International B.V. – Podruznica Zagreb Czech Republic Signify Commercial Czech Republic s.r.o. -

China Railway Signal & Communication Corporation

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. China Railway Signal & Communication Corporation Limited* 中國鐵路通信信號股份有限公司 (A joint stock limited liability company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China) (Stock Code: 3969) ANNOUNCEMENT ON BID-WINNING OF IMPORTANT PROJECTS IN THE RAIL TRANSIT MARKET This announcement is made by China Railway Signal & Communication Corporation Limited* (the “Company”) pursuant to Rules 13.09 and 13.10B of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “Listing Rules”) and the Inside Information Provisions (as defined in the Listing Rules) under Part XIVA of the Securities and Futures Ordinance (Chapter 571 of the Laws of Hong Kong). From July to August 2020, the Company has won the bidding for a total of ten important projects in the rail transit market, among which, three are acquired from the railway market, namely four power integration and the related works for the CJLLXZH-2 tender section of the newly built Langfang East-New Airport intercity link (the “Phase-I Project for the Newly-built Intercity Link”) with a tender amount of RMB113 million, four power integration and the related works for the XJSD tender section of the newly built -

47030-002: Lishui River, Jinshan River

Resettlement Plan May 2015 People’s Republic of China: Jiangxi Pingxiang Integrated Rural-Urban Infrastructure Development Prepared by Shangli Project management office of the Jiangxi Pingxiang Integrated Urban and Rural Infrastructure Improvement Project for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 15 May 2015) Currency unit – yuan (CNY) CNY1.00 = $0.1613 $1.00 = CNY6.2012 ABBREVIATIONS AAOV – average annual output value ADB – Asian Development Bank ADG – Anyuan District Government AHs – affected households APs – affected persons DMS – detailed measurement survey DRC – Development and Reform Committee FGD – female group discussion FSR – feasibility study report HD – house demolition HH – household IA – implementation agency JMG – Jiangxi Municipal Government LA – land acquisition LLFs – land-loss farmers LCG – Luxi County Government M&E – monitoring and evaluation MLS – minimum living security O&M – operation and maintenance PMO – Project Management Office PMG – Pingxiang Municipal Government PMTB – Pingxiang Municipal Transportation Bureau RP – resettlement plan SCG – Shangli County Government WWTP – wastewater treatment plant NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars. This resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area.