Three Women in Search of a Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Verby Komatipoort? Rasseproblematiek in Die Portugees-Afrikaanse Reisverhale Van Elsa Joubert

VERBY KOMATIPOORT? RASSEPROBLEMATIEK IN DIE PORTUGEES-AFRIKAANSE REISVERHALE VAN ELSA JOUBERT. LIZETTE GROBLER Tesis ingelewer ter gedeeltelike voldoening aan die vereistes vir die graad van Magister in die Lettere en Wysbegeerte aan die Universiteit van Stellenbosch. Studieleier Prof. Siegfried Huigen Desember 2005 Ek, die ondergetekende, verklaar hiermee dat die werk in hierdie tesis vervat, my eie oorspronklike werk is en dat ek dit nie vantevore in die geheel of gedeeltelik by enige universiteit ter verkryging van ’n graad voorgelê het nie. Handtekening: Datum: 1 September 2005 Bedankings My opregte dank aan: • My promotor, professor Siegfried Huigen, vir sy lankmoedigheid en skerpsinnige kommentaar • My eksaminatore, professor Louise Viljoen en professor Ena Jansen, vir hul insiggewende terugvoer • My eggenoot, Kobus Grobler, vir sy geduld, liefde, aanmoediging en ondersteuning • My ouers Albé en Suzie Bakker, vir hul gebede, taktvolle onderskraging en liefde • My skoonouers, Kobus en Jessie Grobler, my familie en ander pleitbesorgers vir hul ondersteuning, liefde en gebede • My vriendinne Retha Schoeman, Naomi Bruwer en Jihie Moon vir hul inspirasie en aanmoediging • My oupa, Freddie Bakker, wat my voorgraadse studie moontlik gemaak het • Al die dosente van die Departement Afrikaans en Nederlands, veral dr. Ronel Foster, vir hul hulp en belangstelling. • Mev. Hannie van der Merwe en mnr. Trevor Crowley wat gehelp het met die manuskrip se voorbereiding • My Hemelse Vader vir sy ruim oorskulp en groot genade. Erkennings Hiermee word -

Book Reviews

African Studies Quarterly | Volume 17, Issue 4|February 2018 BOOK REVIEWS Semahagn Gashu Abebe. 2014. The Last Post-Cold War Socialist Federation: Ethnicity, Ideology and Democracy in Ethiopia. London: Routledge. 298 pp. Ethiopia’s ethnic federalism is under stress more than any time since its introduction in 1995. Waves of protest movements in Oromia and Amhara Regional states, in particular, have not given ethnic federalism an easy ride since 2015. Hence, Semahagn Gashu Abebe’s The Last Post- Cold War Socialist Federation is a significant contribution in understanding the sociology of Ethiopian federalism, the political context within which it came into being and is operating, and sheds light on why some ethnic groups are protesting. Abebe’s underlying objective is to explain how the configuration of a Socialist federation in the restructuring of the Ethiopian state makes the transition to and consolidation of democratization and respect for human rights difficult. Organizing the book in eight chapters, Abebe makes a compelling case on the disjuncture between constitutional design and practice in the operation of federalism in Ethiopia. His main hypothesis is that the ideological and political tenets of the TPLF/EPRDF, the ruling coalition since 1991, are more important than the formal constitutional rules in the operation of the federal system. Precisely because of this, he contends that there are two parallel constitutional systems in Ethiopia. In order to test this hypothesis, Abebe explores and examines in detail the scholarship on federal theory and comparative federalism in the first and second chapters. After examining the origin, essential components, basic features, and operation of democratic multi- cultural federations, Abebe could not find comparative relevance for the Ethiopian federal experiment in these systems. -

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin

Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin To cite this version: Denis-Constant Martin. Sounding the Cape, Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa. African Minds, Somerset West, pp.472, 2013, 9781920489823. halshs-00875502 HAL Id: halshs-00875502 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00875502 Submitted on 25 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Sounding the Cape Music, Identity and Politics in South Africa Denis-Constant Martin AFRICAN MINDS Published by African Minds 4 Eccleston Place, Somerset West, 7130, South Africa [email protected] www.africanminds.co.za 2013 African Minds ISBN: 978-1-920489-82-3 The text publication is available as a PDF on www.africanminds.co.za and other websites under a Creative Commons licence that allows copying and distributing the publication, as long as it is attributed to African Minds and used for noncommercial, educational or public policy purposes. The illustrations are subject to copyright as indicated below. Photograph page iv © Denis-Constant -

Places We Belong As by the Places We Do Not—A Truth That Crystalises

places we belong as by the places we do not—a Plessis: Hy was ’n rukkie pagter hier (Heilna du Plooy); Pieter truth that crystalises towards the end of the collection Fourie: Teatermaker (Fanie Olivier); breyten breytenbach: (66): woordenaar, woordnar (Francis Galloway); Johann de I remember that I too am not from around these parts Lange 60: ’n Huldiging (Daniel Hugo) en Reza de Wet: Die That this city, this town is not my own dramaturg as dromer (Temple Hauptfleisch en Marisa Although I cannot erase it Keuris). Die volgende publikasies in die reeks is in From my being produksie: huldigingsbundels oor Elsa Joubert, Antjie Krog, Bartho Smit, Anna M. Louw, Ina Rousseau en Ndoro finds herself, then, in the realisation that the Wilma Stockenström. kind of belonging promised by society is not the In die 21ste eeu is daar ’n merkwaardige toename belonging she seeks. Her disillusionment is also a in die belangrikheid van pryse in die letterkunde en moment of promising truth (70): die kunste. Wat die Suid-Afrikaanse Akademie vir Curse is Wetenskap en Kuns se literêre toekennings betref, het you will never fit in die dramatoekennings van meet af aan telkens swaar Blessing is gedra aan omstredenheid. you will never want to Talle polemieke en debatte rondom prys- toekennings, asook die kom en gaan van pryse deur We need to reimagine what it means to belong— die jare, dui daarop dat literêre toekennings nooit beyond the binaries, the borders, the rigidity that seeks outonoom kan funksioneer nie. Dit staan altyd in to cement belonging but in reality only displaces us and verhouding tot opvattings oor waardeoordeel, smaak alienates us from the world. -

2014 Research Articles

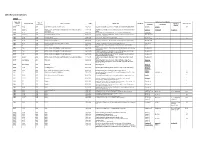

2014 Research Articles: DHET Approved Author(s) of Contribution Year of Journal Journal Number Titles of Journal ISSN Article Title CESM Cat All Other Units claimed Publication 1st Author 2nd Author Listing Authors DHET 30 (2) 2014 South African Journal of Critical Care 1562-8264 A Survey of cultural competence of critical care nurses in KwaZulu-Natal De Beer J Chipps J 0.5 DHET Suppl 1:2 2014 African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance 1117-4315 Significance of literature when constructing a theory: A selective literature Linda NS Phetlhu DR Klopper HC 1 (AJPHERD) review DHET 11 (2) 2014 LitNet Akademies 1995-5928 Die verrekening van taalvariasie in die prosawerk van Elias P Nel Hendricks F 1 DHET 37 (3 & 4) 2014 Anthropology Southern Africa 0258-0144 Landscape, complicity and partitioned zones at South Africa Forest and Grunebaum H 1 Lubya in Israel-Palestine DHET 12 (4) 2014 Art South Africa 1684-6133 Peter Clarke: In Memoriuam 1929-2014 Maurice E 1 DHET 30 (3) 2014 Journal of Literary Studies 0256-4718 Figuring the Animal in Post-apartheid South Africa Woodward W Lemmer E 0.5 DHET 31 (4) 2014 Journal of Literary Studies 0256-4718 The post-humanist Gaze: Reading Fanie jasons Photo Essay on Carting Woodward W 1 Lives DHET 68 (2) 2014 Bulletin of the National Library of South Africa 1562-9392 A strange antipathy: Elsa Joubert and Poppie Nongena Graham LV 1 DHET 42 2014 Acta Germanica 0065-1273 Der Aspekt der Einfühlungsästhetik in Andre Brinks The Other Side of Rath L 1 Silence DHET 3 (2) 2014 African Journal -

Poppie Nongena Enthralling Musical Theatre

FEBRUARY,1985 Vol 9 No 1 ISSN 0314 - 0598 New David Williamson Play SONS OF KANE BY DAVID WILLIAMSON Directed by David Williamson Set and costume design by Shaun Gurton Cast: Noel Ferrier, John Gregg, Max Cullen, Sandy Gore, Libby Clark and Genevieve Picot Theatre Royal t is now almost four years since David I Williamson's last play THE PERFEC TIONIST was premiered and in that time he has been working in other media creating a screenplay of THE PERFEC TIONIST and writing THE LAST BASTION for television. But the attrac tion of the theatre was too great for him to stay away from live performance for long and a chance conversation with journalists in a pub one night provided the inspiration for a new play. SONS OF KANE is about crime and cor ruption, an issue on which David Williamson has not focused his attention since THE REMOVALISTS in 1981 Poppie Nongena (coincidentally to be remounted at Phillip Street Theatre later this month). The Enthralling Musical Theatre managing editor of a big newspaper em pire (played by John Gregg) uncovers Based on a novel by Elsa Joubert critic of The Guardian newspaper as one clear evidence that an honest cop has Written for the stage by Elsa Joubert and of the most impressive pieces of drama to been moved out of the force because he's Sandra Kotze emerge from South Africa in the past too much trouble. The idealism of youth Directed by Hilary Blecher decade, this production has taken Lon is rekindled and he brings in one of his Music by Sophie Mgcina don and New York by storm, collecting a friends (played by Max Cullen) whose Designed by Douglas Heap Lighting design by James Baird number of awards, including the career has taken a downturn to in Cast: Thulia Dumakude, Sophie Mgcina, prestigious Obie (for Outstanding vestigate the whole affair. -

Boeke Wat Skrywers Laat Skryf DEUR SJ NAUDÉ

AFRIKAANSEPEN AFRIKAANS WETENSKAPFIKSIE Boeke wat skrywers laat skryf DEUR SJ NAUDÉ ie ware oorsprong van stories is dikwels Donker materie onmoontlik om te identifiseer. As ’n skrywer dínk Hierdie inskrywings in die brein, soos graverings in klip, Dhy kan die impulse vir sy verhaal of roman word eindelik op redelik duistere manier omvorm tot teks. akkuraat eien, misgis hy hom. Of dan tas hy maar ’n So ’n idee van ’n misterieuse – selfs mistieke – omtowering blekerige wortel raak te midde van wyd vertakkende van lewenservaring tot kuns klink dalk romanties, maar dit netwerke van potensiële oorspronge en invloede. ’n is hoe ek dit ervaar. En ek is lugtig om te hard te dink oor Penwortel is daar nie. hoe die kreatiewe prosesse werk. Daar is natuurlik Om ’n beginpunt te probeer uitwys is soos om die kern skrywers wat selfs vermy om hulself aan psigoterapie te van ’n persoonlikheid – van ’n individu se psigologie – te onderwerp. So ver sou ek nie gaan nie. Terapie kan nuttig wil identifiseer. Dit sou ’n oneindige regressie behels, soos wees, kan die bestaan van vérdere sale vol spieëls onthul. om die oorspronklike subjek te probeer vind in ’n saal van Maar ’n te diepe ondersoek na die meganismes van eie spieëls. Veral romans is ’n mens se lewe lank reeds in kreatiwiteit moet dalk liefs agterweë bly. wording. Al val ’n idee mens skynbaar uit die bloute binne, Die enigsins amateuragtige psigologiese model vir is dit reeds deur vele lae van sediment gefilter – ’n leeftyd kreatiwiteit hierbo is natuurlik nie volledig nie. Dit is altyd van ervarings vorm response op kreatiewe impulse. -

A Short History of Mozambique Malyn Newitt

and DELTA Books Catalogue 2018 JANUARY 2018 A Short History of Mozambique Malyn Newitt This comprehensive history traces the evolution of modern Mozambique, from its early modern origins in the Indian Ocean trading system and the Portuguese maritime empire to the fifteen- year civil war that followed independence and its continued after- effects. Though peace was achieved in 1992 through international mediation, Mozambique’s remarkable recovery has shown signs of stalling. Malyn Newitt explores the historical roots of Mozambican disunity and hampered development, beginning with the divisive effects of the slave trade, the drawing of colonial frontiers in the 1890s and the lasting particularities of the provinces. This book seeks to distil this complex history, and to understand why, twenty-five years after the Peace Accord, Mozambicans still remain among the poorest people in the world. R270 978-1-86842-852-6 Malyn Newitt was Deputy Vice Chancellor of Exeter 978-1-86842-853-3 (e) University and first holder of the Charles Boxer Chair at King’s 216x138mm | 274pp College London. He is author of more than twenty books on Southern Africa rights Portugal and Portuguese colonial history. He retired in 2005. FEBRUARY 2018 The Expert Landlord Managing Your Residential Property like a Pro David Beattie You have a residential investment property. Perhaps you are already renting it out. But are you doing it like a pro and do you know how to maximise your return from it? In this book, property management expert David Beattie distils two decades of experience into easy-to-implement steps and shows you how to manage your property like a professional landlord. -

JEWISH AFFAIRS, the SA Jewish Board of Deputies Aims to Produce a Cultural Forum Which Caters for a Wide Variety of Interests in the Community

MISSION In publishing JEWISH AFFAIRS, the SA Jewish Board of Deputies aims to produce a cultural forum which caters for a wide variety of interests in the community. JEWISH AFFAIRS aims to publish essays of scholarly research on all subjects of Jewish interest, with special emphasis on aspects of South African Jewish life and thought. It will promote Jewish cultural and creative achievement in South Africa, and consider Jewish traditions and heritage within the modern context. It aims to provide future researchers with a window on the community’s reaction to societal challenges. In this way the journal hopes critically to explore, and honestly to confront, problems facing the Jewish community both in South Africa and abroad, by examining national and international affairs and their impact on South Africa. The freedom of speech exercised in this journal will exclude the dissemination of propaganda, personal attacks or any material which may be regarded as defamatory or malicious. In all such matters, the Editor’s decision is final. EDITORIAL BOARD EXECUTIVE EDITOR David Saks SA Jewish Board of Deputies ACADEMIC ADVISORY BOARD Dr Louise Bethlehem Hebrew University of Jerusalem Marlene Bethlehem SA Jewish Board of Deputies Cedric Ginsberg University of South Africa Professor Marcia Leveson Naomi Musiker Archivist and Bibliographer Gwynne Schrire SA Jewish Board of Deputies Dr Gabriel A Sivan World Jewish Bible Centre Professor Gideon Shimoni Hebrew University of Jerusalem Professor Milton Shain University of Cape Town © South African Jewish Board of Deputies Permission to reprint material from JEWISH AFFAIRS should be applied for from The South African Jewish Board of Deputies Original, unpublished essays of between 1000 and 6000 words are invited, and should be sent to: The Editor, [email protected] JEWISH AFFAIRS Vol. -

1414 African Writers Series

African writers series: celebrating over 40 years of African literature Part 1 NEVILLE ADONIS New arrivals in the African writers series (contemporary writers) are Assistant Director: General Services Tom Naudé with his Dance of the rain and Daniel Ojong with his Mysteries from Ayukaba Village. he purpose of introducing the African writers series is to high- Driven by the popularity of the series, a list of Africa’s Best 100 Books light the literary value and the impact of African literature on the was introduced. Rigorous criteria were applied, which included the political systems of countries in Africa in the continuous struggle assessment of quality, the ability to provide new information and the T extent to which a book breaks boundaries. The list comprises 100 for freedom and democracy. This article will run as a two-part series with the final Africa top 100 best books of Africa depicting the impact of African writing on world Best Books of the 20th Century appearing in part two. literature. Considering the criteria, a surprising number of South African The African writers series comprises a classic collection of literary authors and their books were selected. They include: Elsa Joubert with fiction, short stories, poetry, translations, drama and non-fiction written Die swerfjare van Poppie Nongena; Nadine Gordimer with Burger’s by authors of African descent. These books have literary value and daughter; Wally Serote with Third World express; Alan Paton with Cry, are mainly used as setwork material in schools. Widely published the beloved country; Nelson Mandela with Long walk to freedom; by Heinemann since 1962, this series recently celebrated its 40th Eugene Marais with Die siel van die mier and Antjie Krog with Country anniversary. -

Karen Blixen in the African Book and Literary Tourism Market

Johann Lodewyk Marais Karen Blixen in the African book Johann Lodewyk Marais is a writer, and literary tourism market literary critic and historian. He is a research fellow in the Unit for Academic Literacy, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. Email: [email protected] Karen Blixen in the African book and literary tourism market In 1937, the Danish-born writer Karen Blixen published Out of Africa, an autobiographical account, in English, of the seventeen years she spent in Africa (from 1914 until 1931). During those years, she forged a permanent bond with Kenya, where she managed a coffee plantation. This bond was immortalised in the book, leading to cult status for both the publication and its author. Out of Africa contains a blend of the essay, the sketch and the historical document. A contemporary reading of the book also reveals some offensive and racist passages; footprints, as it were, of the settler society of its day. However, the lyrical, introspective quality of this book has resulted in its becoming one of the great publishing phenomena of the twentieth century, reaching many readers through various reprints, translations and a film version. This article presents the publishing history of Out of Africa and gives an overview of its many translations across the globe. It also indicates the extent to which, and the reasons why, the book did (or did not) achieve success in Africa. A comparison is also made between Out of Africa and a number of texts by other female writers who wrote about their experiences particularly in African landscapes and/or places. -

Elsa Joubert: 'N Kommunikatiewe Benadering

ELSA JOUBERT: 'N KOMMUNIKATIEWE BENADERING deur Dietloff Zigfried van der Berg Proefskrif voorgele ter gedeeltelike vervulling van die vereistes vir die Ph.D.-graad in Afrikaans en Nederlands in die Fakulteit Lettere en Wysbegeerte aan die Universiteit van Natal, Pietermaritzburg. Promotor: Prof. W. F. Jonckheere Junie 1993 Hiermee wil ek graag my dank betuig aan al die mense wat op soveel verskillende maniere daartoe bygedra het dat hierdie proefskrif voltooi kon word. My besondere dank aan professor Wilfred Jonckheere vir sy leiding, dominee Johan Spies vir sy programmering en aan Elizabeth vir jare se ondersteuning en geduldige Iyding. ELSA JOUBERT: 'N KOMMUNIKATIEWE BENADERING INHOUD 1 TEORETIESE ORleNTERING 1.1 Letterkundige benaderings 3 1.1.1 Mimetiese orientasie 6 1.1.2 Ekspressiewe teoriee 9 1.1.3 Objektiewe teoriee 12 1.1.4 Pragmatiese teoriee 15 1.2 Kommunikasiemodelle 17 1.2.1 Lineere model 18 1.2.2 Interaksionele model 19 1.2.3 Jakobson-model 20 1.2.4 Ontvangersmodel 24 1.2.5 Lesersmodel 28 1.2.5.1 Ooreenkomste 33 1.2.5.2 Verskille 36 1.3 Kommunikatiewe romankomponente 40 1.3.1 Sender c< S,! • r 48 1.3.1.1 Spraakweergawe 50 1.3.1 .2 Direkte vertellers 52 1.3.1.3 Indirekte vertellers 54 1.3.2 Boodskap 59 1.3.2.1 Karakter 62 1.3.2.2 Handeling 65 1.3.2.3 Tyd 70 1.3.2.4 Ruimte 72 1.3.3 Ontvanger 74 -1- 2 ONS WAG OP DIE KAPTEIN 2.1 Strategiese vaardigheid 78 2.2 Taalvaardigheid 91 2.2.1 Funksionele vaardigheid 92 2.2.2 Tekstuele vaardigheid 95 2.2.2.1 Koherensie 98 2.2.2.2 Tema 112 2.2.2.3 Tydruimte 124 2.2.2.4 Retorika 126 2.2.3