File No.: Sct-4001-14 Citation: 2017 Sctc 2 Date: 20170621

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Needs Assessment

NEEDS ASSESSMENT 105-1555 St. James Street p. (204) 946-1869 [email protected] Winnipeg, Manitoba f. (204) 946-1871 www.scoinc.mb.ca R3H1B5 2 Table of Contents Southern Chiefs’ Organization Mandate and Member First Nations………………………….3 Summary………………………………………………………………………………………………….4 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………………5 Background………………………………………………………………………………………………6 Needs Assessment Goal and Objectives…………………………………………………………..7 A Socio-Ecological Approach to Violence Prevention………………………………………….8 A Brief Socio-Ecological Analysis of Violence Against Indigenous Women and Girls…..11 Literature Review………………………………………………………………………………………13 Methods…………………………………………………………………………………………………18 Results…………………………………………………………………………………………………....22 Discussion…………………………………………………………………………………………….…43 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………………………..…….46 References………………………………………..…………………………………………………….47 Appendix A: Data Collection Tools……………………………………………...…………………51 Appendix B: Partners………………………………………………………...………………………..67 Authors: Tessa Jourdain, Master of Public Health (Health Promotion) Candidate, Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto Shauna Fontaine, Violence Prevention and Safety Coordinator, Southern Chiefs’ Organization 3 Southern Chiefs’ Organization Mandate Established in 1998, the Mandate of the Southern Chiefs Organization (SCO) is to protect, preserve, promote and enhance First Nation peoples’ inherent rights, languages, customs and traditions through the application and implementation of the spirit and intent -

Sagkeeng First Nation: Developmental Impacts and the Perception of Environmental Health Risks©

Sagkeeng First Nation: Developmental Impacts and the Perception of Environmental Health Risks© by Brenda Elias John D. O’Neil Annalee Yassi Benita Cohen Department of Community Health Sciences University of Manitoba For additional copies of this report please contact CAHR office at 204-789-3250 April 1997 SAGKEENG FIRST NATION: DEVELOPMENT IMPACTS AND THE PERCEPTION OF ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH RISKS FINAL REPORT BRENDA ELIAS JOHN O’NEIL ANNALEE YASSI BENITA COHEN University of Manitoba Northern Health Research Unit Occupational and Environmental Health Unit Department of Community Health Sciences Faculty of Medicine (c) April 1997 Funding provided by the National Health Research and Development Program NHRDP Project No. 6607-1620-63 1 1.0 Introduction In 1988, a critical assessment was conducted on how governments and industry address potential health impacts of industrial developments in northern regions of Canada. The Canadian Environmental Assessment Research Council (CEARC) held several regional workshops across Canada to foster discussion on northern and Aboriginal understandings of environmental health issues. Many broad recommendations emerged: ∗ the health of a community should be understood before a development project is underway; ∗ the impacts of an existing industrial site on a community over time should be understood by actually studying whether there is industry-related diseases (such as cancer or lung problems) developing in that community; ∗ a communication approach that provides scientific information on contaminants to northern communities should be developed; ∗ a constructive and respectful way of understanding what northerners consider to be a danger to their health should be developed. This study is a critical response to these recommendations. It examines the cultural basis of risk perception and the importance of local knowledge in changing the assessment and management of health risks. -

Treaties in Canada, Education Guide

TREATIES IN CANADA EDUCATION GUIDE A project of Cover: Map showing treaties in Ontario, c. 1931 (courtesy of Archives of Ontario/I0022329/J.L. Morris Fonds/F 1060-1-0-51, Folder 1, Map 14, 13356 [63/5]). Chiefs of the Six Nations reading Wampum belts, 1871 (courtesy of Library and Archives Canada/Electric Studio/C-085137). “The words ‘as long as the sun shines, as long as the waters flow Message to teachers Activities and discussions related to Indigenous peoples’ Key Terms and Definitions downhill, and as long as the grass grows green’ can be found in many history in Canada may evoke an emotional response from treaties after the 1613 treaty. It set a relationship of equity and peace.” some students. The subject of treaties can bring out strong Aboriginal Title: the inherent right of Indigenous peoples — Oren Lyons, Faithkeeper of the Onondaga Nation’s Turtle Clan opinions and feelings, as it includes two worldviews. It is to land or territory; the Canadian legal system recognizes title as a collective right to the use of and jurisdiction over critical to acknowledge that Indigenous worldviews and a group’s ancestral lands Table of Contents Introduction: understandings of relationships have continually been marginalized. This does not make them less valid, and Assimilation: the process by which a person or persons Introduction: Treaties between Treaties between Canada and Indigenous peoples acquire the social and psychological characteristics of another Canada and Indigenous peoples 2 students need to understand why different peoples in Canada group; to cause a person or group to become part of a Beginning in the early 1600s, the British Crown (later the Government of Canada) entered into might have different outlooks and interpretations of treaties. -

Horse Traders, Card Sharks and Broken Promises: the Contents of Treaty #3 a Detailed Analysis December 21, 2011

Horse Traders, Card Sharks and Broken Promises: The Contents of Treaty #3 A Detailed Analysis December 21, 2011 Many people have studied, written about and talked about Canada's 1873 Treaty #3 with the Saulteaux Anishnaabek over 55,000 square miles west of Lake Superior. We are not the first nor the last. We are not legal experts or historians. Being grandmothers, we have skills of observation and commitment to future generations. Our views are our own. We don't claim to represent any community, tribe or nation though we are confident many people agree with us. We do think everyone in this land has a duty to know about the history that has brought us to this time. Our main purpose here is to prompt discussion of these important matters. Treaty 3 was a definitive one that shaped the terms of the next several Treaties 4 - 7. Revisions to 1 and 2 also resulted from it. The later treaties used Treaty 3 as a role model. For the 1905 Treaty 9 with the James Bay Cree, this was difficult because the Dominion Government was trying to pay even less for the Cree territory than they had for the Saulteaux Ojibwe territory. The Cree were fully aware of what had gone on. In our view, a Treaty is something that must be reviewed, renewed and reconfirmed at regular intervals in order for it to maintain its authority with the signatories. If anyone fails to adhere to the Treaty terms, then it becomes a broken Treaty no longer valid. Can a broken jug hold water? INTENT OF THE TREATIES - A Program to Steal the Land by Conciliatory Methods (Note#4,5) In this article, we examine some of the key elements of Treaty #3 aka the North-West Angle Treaty. -

Resolutions Update Report for 2012 Aga Resolutions

ASSEMBLY OF FIRST NATIONS RESOLUTIONS UPDATE REPORT FOR 2012 AGA RESOLUTIONS Chief Garrison Settee, 1 Missing and Murdered Indigenous Chief Perry Bellegarde, Pimicikamak Okimawin, Women and Girls, 2012 Cross Lake, MB Little Black Bear First Nation, SK THEREFORE BE IT RESOLVED that the Chiefs-in-Assembly: 1. Make a personal and public declaration to take full responsibility to be violence free and commit to taking all actions available to them to uphold and ensure the rights of Indigenous women and girls. 2. Affirm: a. that further to Resolution 61/2010, the AFN call upon Canada to jointly establish an independent, public commission into missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada. b. that further to Resolution 02/2011, the AFN call upon Canada to convene a Royal Commission on Violence against Indigenous Girls and Women to make concrete and specific recommendations to end violence against Indigenous girls and women at a national level. c. the direction for the AFN to demand that the Government of Canada support community based- initiatives and national programs that seek to promote public awareness and carry out advocacy and research about violence against Indigenous women; restore funding to the Native Women’s Association of Canada (NWAC) for maintenance of a national database on missing and murdered Indigenous women; and, ensure proper facilities and services are available within communities for those whom are victims or have lost their loved ones through acts of violence. d. the direction to the AFN and the National Chief to strongly advocate for the full protection and safety of First Nations women across Canada. -

Annual Report 2009–2010

Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Tourism Annual Report 2009–2010 His Honour the Honourable Philip S. Lee, C.M., O.M. Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba Room 235, Legislative Building Winnipeg, MB R3C 0V8 May It Please Your Honour: I have the privilege of presenting for the information of your honour the Annual Report of Manitoba Culture, Heritage and Tourism for the fiscal year ending March 31, 2010. Respectfully submitted, "Original Signed By Flor Marcelino" Honourable Flor Marcelino Minister of Culture, Heritage and Tourism Deputy Minister’s Office Room 112 Legislative Building Winnipeg MB R3C 0V8 T 204-945-3794 F 204-948-3102 www.manitoba.ca/chc/ Honourable Flor Marcelino Minister of Culture, Heritage and Tourism Dear Minister Marcelino: I hav e t he hon our of s ubmitting f or y our ap proval t he 200 9–2010 Annual R eport f or Mani toba C ulture, Heritage and Tourism. The department had lead responsibility for Manitoba’s participation in the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Games in Vancouver. Staff oversaw the development, construction and operation of the award-winning Manitoba pavilion (CentrePlace) that drew 120,000 people. Manitoba’s partnership exhibit with the Canadian Museum for Human Rights generated substantial awareness for the Museum. Other Olympics initiatives s upported b y t he department i ncluded t he O lympic T orch R elay t hrough 33 c ommunities, representation of Manitoba artists in the Cultural Olympiad, Place de la Francophonie, the Manitoba Day Victory Celebration concert, and the Aboriginal Youth Gathering. In January, the year-long Man itoba Homecoming 2010 initiative was launched, inviting Man itobans and former Manitobans to celebrate all the great events, activities and attractions our province has to offer. -

Copy of Green and Teal Simple Grid Elementary School Book Report

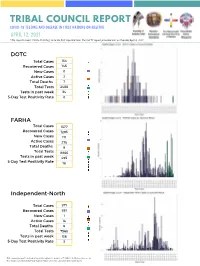

TRIBAL COUNCIL REPORT COVID-19 TESTING AND DISEASE IN FIRST NATIONS ON RESERVE APRIL 12, 2021 *The reports covers COVID-19 testing since the first reported case. The last TC report provided was on Tuesday April 6, 2021. DOTC Total Cases 154 Recovered Cases 145 New Cases 0 Active Cases 2 Total Deaths 7 Total Tests 2488 Tests in past week 34 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 0 FARHA Total Cases 1577 Recovered Cases 1293 New Cases 111 Active Cases 275 Total Deaths 9 Total Tests 8866 Tests in past week 495 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 18 Independent-North Total Cases 871 Recovered Cases 851 New Cases 1 Active Cases 14 Total Deaths 6 Total Tests 7568 Tests in past week 136 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 3 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. APRIL 12, 2021 Independent- South Total Cases 218 Recovered Cases 214 New Cases 1 Active Cases 2 Total Deaths 2 Total Tests 1932 Tests in past week 30 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 6 IRTC Total Cases 380 Recovered Cases 370 New Cases 0 Active Cases 1 Total Deaths 9 Total Tests 3781 Tests in past week 55 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 0 KTC Total Cases 1011 Recovered Cases 948 New Cases 39 Active Cases 55 Total Deaths 8 Total Tests 7926 Tests in past week 391 5-Day Test Positivity Rate 10 This summary report is intended to provide high-level analysis of COVID-19 testing and disease in First Nations on reserve by Tribal Council Region since first case until date noted above. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Section M: Community Support

Section M: Community Support Page 251 of 653 Community Support Health Canada’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services has developed the Children’s Services Reference Chart for general information on what types of health services are available in the First Nations’ communities. Colour coding was used to indicate where similar services might be accessible from the various community programs. A legend that explains each of the colours /categories can be found in the centre of chart. By using the chart’s colour coding system, resource teachers may be able to contact the communities’ agencies and begin to open new lines of communication in order to create opportunities for cost sharing for special needs services with the schools. However, it needs to be noted that not all First Nations’ communities offer the depth or variety of the services described due to many factors (i.e., budgets). Unfortunately, there are times when special needs services are required but cannot be accessed for reasons beyond the school and community. It is then that resource teachers should contact Manitoba’s Regional Advisor for Children Special Services to ask for direction and assistance in resolving the issue. Manitoba’s Regional Advisor, Children’s Special Services, First Nations and Inuit Health Programs is Mary L. Brown. Phone: 204-‐983-‐1613 Fax: 204-‐983-‐0079 Email: [email protected] On page two is the Children’s Services Reference Chart and on the following page is information from the chart in a clearer and more readable format including -

Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory

Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory September 2017 CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples & Traditional Territory September 2017 The following document offers the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) recommended territorial acknowledgement for institutions where our members work, organized by province. While most of these campuses are included, the list will gradually become more complete as we learn more about specific traditional territories. When requested, we have also included acknowledgements for other post-secondary institutions as well. We wish to emphasize that this is a guide, not a script. We are recommending the acknowledgements that have been developed by local university-based Indigenous councils or advisory groups, where possible. In other places, where there are multiple territorial acknowledgements that exist for one area or the acknowledgements are contested, the multiple acknowledgements are provided. This is an evolving, working guide. © 2016 Canadian Association of University Teachers 2705 Queensview Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K2B 8K2 \\ 613-820-2270 \\ www.caut.ca Cover photo: “Infinity” © Christi Belcourt CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples and Traditional Territory September 2017 Contents 1| How to use this guide Our process 2| Acknowledgement statements Newfoundland and Labrador Prince Edward Island Nova Scotia New Brunswick Québec Ontario Manitoba Saskatchewan Alberta British Columbia Canadian Association of University Teachers 3 CAUT Guide to Acknowledging First Peoples and Traditional Territory September 2017 1| How to use this guide The goal of this guide is to encourage all academic staff context or the audience in attendance. Also, given that association representatives and members to acknowledge there is no single standard orthography for traditional the First Peoples on whose traditional territories we live Indigenous names, this can be an opportunity to ensure and work. -

Regional Stakeholders in Resource Development Or Protection of Human Health

REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS IN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT OR PROTECTION OF HUMAN HEALTH In this section: First Nations and First Nations Organizations ...................................................... 1 Tribal Council Environmental Health Officers (EHO’s) ......................................... 8 Government Agencies with Roles in Human Health .......................................... 10 Health Canada Environmental Health Officers – Manitoba Region .................... 14 Manitoba Government Departments and Branches .......................................... 16 Industrial Permits and Licensing ........................................................................ 16 Active Large Industrial and Commercial Companies by Sector........................... 23 Agricultural Organizations ................................................................................ 31 Workplace Safety .............................................................................................. 39 Governmental and Non-Governmental Environmental Organizations ............... 41 First Nations and First Nations Organizations 1 | P a g e REGIONAL STAKEHOLDERS FIRST NATIONS AND FIRST NATIONS ORGANIZATIONS Berens River First Nation Box 343, Berens River, MB R0B 0A0 Phone: 204-382-2265 Birdtail Sioux First Nation Box 131, Beulah, MB R0H 0B0 Phone: 204-568-4545 Black River First Nation Box 220, O’Hanley, MB R0E 1K0 Phone: 204-367-8089 Bloodvein First Nation General Delivery, Bloodvein, MB R0C 0J0 Phone: 204-395-2161 Brochet (Barrens Land) First Nation General Delivery, -

An Agreement to Share

An agreement to share understanding the implications of the MMTP on Indigenous Peoples in a Treaty One context A report prepared for Wa Ni Ska Tan By Aimée Craft May, 2018 A long time ago when the Treaties were made, one of the Chiefs got up and pointed towards the heavens and he said, “The sun is my father, and the land is my mother. They teach us we have a responsibility in our generation, in our lifetime. […] Up to the horizons, beyond that is the seven generations, as far as you can see, that’s our responsibility – to teach those generations about our wisdom and our knowledge about our people.” We have a responsibility to keep the Treaty alive in our lifetime for future generations. - Elder Harry Bone Treaty Relations Commission of Manitoba and Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, Dtantu Balai Betl Nahidei: Our Relations To The Newcomers, vol 3, by Anishinaabe Elder Harry Bone, in Joe Hyslop, Harry Bone and the Treaty & Dakota Elders of Manitoba, with contributions by the AMC Council of Elders (Winnipeg: TRCM & AMC, 2015) [TRCM vol 3]. 2 3 Table of Contents ABOUT THE AUTHOR AND RETAINER 5 DECLARATION 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 I. INTRODUCTION 9 II. A FRAMEWORK FOR RECONCILIATION 12 III. THE UNITED NATIONS DECLARATION ON THE RIGHTS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES 18 IV. WHAT IS THE HONOUR OF THE CROWN AND HOW DOES IT APPLY IN A TREATY ONE CONTEXT, WITH RESPECT TO THE PROPOSED MMTP? 21 V. HOW CAN/SHOULD THE NATIONAL ENERGY BOARD ENGAGE WITH INDIGENOUS LEGAL TRADITIONS IN CONSIDERING THE PROPOSED MMTP? 26 VI.