Language Contact in East Nusantara

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Languages, Local Malay, and Bahasa Indonesia a Case Study from North Maluku

PB Wacana Vol. 14 No. 2 (October 2012) JOHN BOWDENWacana, Local Vol. 14languages, No. 2 (October local Malay, 2012): and 313–332 Bahasa Indonesia 313 Local languages, local Malay, and Bahasa Indonesia A case study from North Maluku JOHN BOWDEN Abstract Many small languages from eastern Indonesia are threatened with extinction. While it is often assumed that ‘Indonesian’ is replacing the lost languages, in reality, local languages are being replaced by local Malay. In this paper I review some of the reasons for this in North Maluku. I review the directional system in North Maluku Malay and argue that features like the directionals allow those giving up local languages to retain a sense of local linguistic identity. Retaining such an identity makes it easier to abandon local languages than would be the case if people were switching to ‘standard’ Indonesian. Keywords Local Malay, language endangerment, directionals, space, linguistic identity. 1 Introduction Maluku Utara is one of Indonesia’s newest and least known provinces, centred on the island of Halmahera and located between North Sulawesi and West Papua provinces. The area is rich in linguistic diversity. According to Ethnologue (Lewis 2009), the Halmahera region is home to seven Austronesian languages, 17 non-Austronesian languages and two distinct varieties of Malay. Although Maluku Utara is something of a sleepy backwater today, it was once one of the most fabled and important parts of the Indonesian archipelago and it became the source of enormous treasure for outsiders. Its indigenous clove crop was one of the inspirations for the great European age of discovery which propelled navigators such as Christopher Columbus and Ferdinand Magellan to set forth on their epic journeys across the globe. -

Manado Malay: Features, Contact, and Contrasts. Timothy Brickell: [email protected]

Manado Malay: features, contact, and contrasts. Timothy Brickell: [email protected] Second International Workshop on Malay varieties: ILCAA (TUFS) 13th-14th October 2018 Timothy Brickell: [email protected] Introduction / Acknowledgments: ● Timothy Brickell – B.A (Hons.): Monash University 2007-2011. ● PhD: La Trobe University 2011-2015. Part of ARC DP 110100662 (CI Jukes) and ARC DECRA 120102017 (CI Schnell). ● 2016 – 2018: University of Melbourne - CI for Endangered Languages Documentation Programme/SOAS IPF 0246. ARC Center of Excellence for the Dynamics of Language (CoEDL) affiliate. ● Fieldwork: 11 months between 2011-2014 in Tondano speech community. 8 months between 2015-2018 in Tonsawang speech community. ● October 2018 - :Endeavour Research Fellowship # 6289 (thank you to Assoc. Prof. Shiohara and ILCAA at TUFS for hosting me). Copyrighted materials of the author PRESENTATION OVERVIEW: ● Background: brief outline of linguistic ecology of North Sulawesi. Background information on Manado Malay. ● Outline of various features of MM: phonology, lexicon, some phonological changes, personal pronouns, ordering of elements within NPs, posessession, morphology, and causatives. ● Compare MM features with those of two indigenous with which have been in close contact with MM for at least 300 years - Tondano and Tonsawang. ● Primary questions: Has long-term contact with indigneous languages resulted in any shared features? Does MM demonstrate structural featues (Adelaar & Prentice 1996; Adelaar 2005) considered characteristic of contact Malay varities? Background:Geography ● Minahasan peninsula: northern tip of Sulawesi, Indonesia. Background: Indigenous language groups ● Ten indigenous language micro-groups of Sulawesi (Mead 2013:141). Approx. 114 languages in total (Simons & Fennings 2018) North Sulawesi indigenous language/ethnic groups: Languages spoken in North Sulawesi: Manado Malay (ISO 639-3: xmm) and nine languages from three microgroups - Minahasan (five), Sangiric (three), Gorontalo-Mongondow (one). -

Spices from the East: Papers in Languages of Eastern Indonesia

Sp ices fr om the East Papers in languages of eastern Indonesia Grimes, C.E. editor. Spices from the East: Papers in languages of Eastern Indonesia. PL-503, ix + 235 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 2000. DOI:10.15144/PL-503.cover ©2000 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. Also in Pacific Linguistics Barsel, Linda A. 1994, The verb morphology of Mo ri, Sulawesi van Klinken, Catherina 1999, A grammar of the Fehan dialect of Tetun: An Austronesian language of West Timor Mead, David E. 1999, Th e Bungku-Tolaki languages of South-Eastern Sulawesi, Indonesia Ross, M.D., ed., 1992, Papers in Austronesian linguistics No. 2. (Papers by Sarah Bel1, Robert Blust, Videa P. De Guzman, Bryan Ezard, Clif Olson, Stephen J. Schooling) Steinhauer, Hein, ed., 1996, Papers in Austronesian linguistics No. 3. (Papers by D.G. Arms, Rene van den Berg, Beatrice Clayre, Aone van Engelenhoven, Donna Evans, Barbara Friberg, Nikolaus P. Himmelmann, Paul R. Kroeger, DIo Sirk, Hein Steinhauer) Vamarasi, Marit, 1999, Grammatical relations in Bahasa Indonesia Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in grammars and linguistic descriptions, dictionaries and other materials on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia, Southeast and South Asia, and Australia. Pacific Linguistics, established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund, is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian National University. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. -

Agustus 2014.Pdf

MASYARAKAT LINGUISTIK INDONESIA Didirikan pada tahun 1975, Masyarakat Linguistik Indonesia (MLI) merupakan organisasi profesi yang bertujuan mengembangkan studi ilmiah mengenai bahasa. PENGURUS MASYARAKAT LINGUISTIK INDONESIA Ketua : Katharina Endriati Sukamto, Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya Wakil Ketua : Fairul Zabadi, Badan Pengembangan dan Pembinaan Bahasa Sekretaris : Ifan Iskandar, Universitas Negeri Jakarta Bendahara : Yanti, Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya DEWAN EDITOR Utama : Bambang Kaswanti Purwo, Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya Pendamping : Lanny Hidajat, Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya Anggota : Bernd Nothofer, Universitas Frankfurt, Jerman; Ellen Rafferty, University of Wisconsin, Amerika Serikat; Bernard Comrie, Max Planck Institute; Tim McKinnon, Jakarta Field Station MPI; A. Chaedar Alwasilah, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia; E. Aminudin Aziz, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia; Siti Wachidah, Universitas Negeri Jakarta; Katharina Endriati Sukamto, Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya; D. Edi Subroto, Universitas Sebelas Maret; I Wayan Arka, Universitas Udayana; A. Effendi Kadarisman, Universitas Negeri Malang; Bahren Umar Siregar, Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya; Hasan Basri, Universitas Tadulako; Yassir Nasanius, Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya; Dwi Noverini Djenar, Sydney University, Australia; Mahyuni, Universitas Mataram; Patrisius Djiwandono, Universitas Ma Chung; Yanti, Universitas Katolik Indonesia Atma Jaya. JURNAL LINGUISTIK INDONESIA Linguistik Indonesia diterbitkan pertama kali pada tahun 1982 dan sejak tahun 2000 diterbitkan tiap bulan Februari dan Agustus. Linguistik Indonesia telah terakreditasi berdasarkan SK Dirjen Dikti No. 040/P/2014, 18 Februari 2014. Jurnal ilmiah ini dibagikan secara cuma-cuma kepada para anggota MLI yang keanggotaannya umumnya melalui Cabang MLI di pelbagai Perguruan Tinggi, tetapi dapat juga secara perseorangan atau institusional. Iuran per tahun adalah Rp 200.000,00 (anggota dalam negeri) dan US$30 (anggota luar negeri). -

Papuan Malay – a Language of the Austronesian- Papuan Contact Zone

Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society JSEALS 14.1 (2021): 39-72 ISSN: 1836-6821, DOI: http://hdl.handle.net/10524/52479 University of Hawaiʼi Press PAPUAN MALAY – A LANGUAGE OF THE AUSTRONESIAN- PAPUAN CONTACT ZONE Angela Kluge SIL International [email protected] Abstract This paper describes the contact features that Papuan Malay, an eastern Malay variety, situated in East Nusantara, the Austronesian-Papuan contact zone, displays under the influence of Papuan languages. This selection of features builds on previous studies that describe the different contact phenomena between Austronesian and non-Austronesian languages in East Nusantara. Four typical western Austronesian features that Papuan Malay is lacking or making only limited use of are examined in more detail: (1) the lack of a morphologically marked passive voice, (2) the lack of the clusivity distinction in personal pronouns, (3) the limited use of affixation, and (4) the limited use of the numeral-noun order. Also described in more detail are six typical Papuan features that have diffused to Papuan Malay: (1) the genitive-noun order rather than the noun-genitive order to express adnominal possession, (2) serial verb constructions, (3) clause chaining, and (4) tail-head linkage, as well as (5) the limited use of clause-final conjunctions, and (6) the optional use of the alienability distinction in nouns. This paper also briefly discusses whether the investigated features are also present in other eastern Malay varieties such as Ambon Malay, Maluku Malay and Manado Malay, and whether they are inherited from Proto-Austronesian, and more specifically from Proto-Malayic. By highlighting the unique features of Papuan Malay vis-à-vis the other East Nusantara Austronesian languages and placing the regional “adaptations” of Papuan Malay in a broader diachronic perspective, this paper also informs future research on Papuan Malay. -

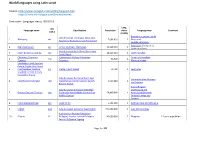

World Languages Using Latin Script

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11. -

29#Suprasegmental#Phonology

29#Suprasegmental#phonology Daniel Kaufman (Queens College, CUNY & ELA) & Nikolaus P. Himmelmann (Universität zu Köln) This%chapter%examines%what%is%an%under2researched%field%encompassing%stress,%tone,% and% intonation.% Apart% from% summarizing% the% relatively% little% that% is% known% about% intonation%in%the%area%under%scrutiny,%the%chapter%is%primarily%concerned%with%stress% systems.%Of%particular%interest%is%that%recent%research%has%suggested%that%for%several% western%Austronesian%languages,%including%most%notably%Indonesian,%stress%is%entirely% absent.% The% sporadic% appearance% of% tone% in% western% Austronesian% languages% (including%Chamic%and%West%New%Guinea)%is%notable%for%the%variety%of%tonal%systems% found%and%the%role%of%contact%with%non2Austronesian%tonal%languages.% 1.0 Introduction In this chapter, we investigate stress, tone and intonation as it relates to western Austronesian languages and offer a typological overview of the region’s prosodic systems. A major focus of the chapter is on the difficulties posed by Austronesian languages for canonical analyses of stress systems. Although the stress systems of many Austronesian languages have been described and most grammars contain a short note on stress, these descriptions have been almost entirely impressionistic. It is now clear that perception biases have colored these impressions and, as a result, wide swaths of the descriptive literature. A small body of work examines this problem with regard to Malay varieties and concludes that several of these varieties, contrary to traditional descriptions, show no word stress at all. On this analysis, typical correlates of stress, i.e. prominence in pitch, duration and intensity, originate on the phrase level rather than the word level. -

Ternate Malay : Grammar and Texts Date: 2012-10-11

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/19945 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Litamahuputty, Betty Title: Ternate Malay : grammar and texts Date: 2012-10-11 1 Introduction Ternate Malay is a variety of Malay spoken on the island of Ternate, a small island in the eastern part of the Indonesian archipelago. It is one of the main languages on the island. The majority of speakers live in Ternate town, where it is used as a mother tongue as well as the language of communication between people of various ethnic and linguistic backgrounds. Malay varieties in eastern Indonesia received some scholarly attention in the 1980s and 1990s. In 1980, James T. Collins published a booklet on Ambon Malay, discussing it in terms of creolization theories of that time (Collins 1980). Almost a decade earlier, Paramita R. Abdurachman wrote on Portuguese loanwords in Ambon Malay (Abdurachman 1972). In the decades to follow, some more varieties were studied and various articles and descriptions of Malay in eastern Indonesia were published. A number of PhD dissertations were written, including: a description of word and phrase structures in Larantuka Malay (Kumanireng 1993); a phonology, morphology, and syntax of Ambon Malay (Van Minde 1997); a grammar of Manado Malay (Stoel 2005); and a typological comparison of seven Malay varieties of eastern Indonesia, including Banda Malay, Kupang Malay and Papua Malay (Paauw 2009). A description of Ternate Malay may complete this series. One of the challenges encountered in the study of the Ternate Malay variety (which might also occur in other varieties and languages) is the flexibility of lexical items and the limited overt marking of grammatical features on these items. -

Gazetteer Service - Application Profile of the Web Feature Service Best Practice

Best Practices Document Open Geospatial Consortium Approval Date: 2012-01-30 Publication Date: 2012-02-17 External identifier of this OGC® document: http://www.opengis.net/doc/wfs-gaz-ap ® Reference number of this OGC document: OGC 11-122r1 Version 1.0 ® Category: OGC Best Practice Editors: Jeff Harrison, Panagiotis (Peter) A. Vretanos Gazetteer Service - Application Profile of the Web Feature Service Best Practice Copyright © 2012 Open Geospatial Consortium To obtain additional rights of use, visit http://www.opengeospatial.org/legal/ Warning This document defines an OGC Best Practices on a particular technology or approach related to an OGC standard. This document is not an OGC Standard and may not be referred to as an OGC Standard. This document is subject to change without notice. However, this document is an official position of the OGC membership on this particular technology topic. Document type: OGC® Best Practice Paper Document subtype: Application Profile Document stage: Approved Document language: English OGC 11-122r1 Contents Page 1 Scope ..................................................................................................................... 13 2 Conformance ......................................................................................................... 14 3 Normative references ............................................................................................ 14 4 Terms and definitions ........................................................................................... 15 5 Conventions -

The Poetic Power of Place

The PoeTic Power of Place comparative perspectives on austronesian ideas of locality The PoeTic Power of Place comparative perspectives on austronesian ideas of locality edited by James J. fox a publication of the department of anthropology as part of the comparative austronesian project, research school of pacific studies the australian national university canberra ACT australia Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au Previously published in Australia by the Department of Anthropology in association Australian National University, Canberra 1997. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry The poetic power of place: comparative perspectives on Austronesian ideas of locality. Bibliography. Includes Indeex ISBN 0 7315 2841 7 (print) ISBN 1 920942 86 6 (online) 1. Place (Philosophy). 2. Sacredspace - Madagascar. 3. Sacred space - Indonesia. 4. Sacred space - Papua New Guinea. I. Fox, James J., 1940-. II. Australian National University. Dept. of Anthropology. III. Comparative Austronesian Project. 291.35 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Typesetting by Margaret Tyrie/Norma Chin, maps and drawings by Keith Mitchell/Kay Dancey Printed at National Capital Printing, Canberra © The several authors, each in respect of the paper presented, 1997 This edition © 2006 ANU E Press Inside Austronesian Houses Table of Contents Acknowledgements ix Chapter 1. Place and Landscape in Comparative Austronesian Perspective James J. Fox 1 Introduction 1 Current Interest in Place and Landscape 2 Distinguishing and Valorizing Austronesian Spaces 4 Situating Place in a Narrated Landscape 6 Topogeny: Social Knowledge in an Ordering of Places 8 Varieties, Forms and Functions of Topogeny 12 Ambiguities and Indeterminacy of Place 15 References 17 Chapter 2. -

A Description of Ternate Malay

PB Wacana Vol. 14 No. 2 (October 2012) BETTYWacana LITAMAHU Vol. 14PUTTY No. 2, A(October description 2012): of Ternate 333–369 Malay 333 A description of Ternate Malay BETTY LITAMAHUPUTTY Abstract Ternate Malay is a local variety of Malay in Ternate, a small island in the Maluku Utara province in eastern Indonesia. The majority of speakers live in Ternate town, where it serves as mother tongue as well as a means of communication between people of various ethnic and linguistic backgrounds. In the last few decades there is a growing scholarly interest in local Malay varieties, particularly in the eastern part of Indonesia. This article is a short description of Ternate Malay based on the idea that words in Ternate Malay receive their meaning in the combination with other words and that the linguistic context as well as the non-linguistic situation in which they occur, determine the most suitable interpretation of utterances. It is shown how certain words facilitate the determination of the interpretation. Keywords Malay dialects, linguistics, grammar, Ternate, Maluku Utara. Introduction1 Ternate Malay is a variety of Malay spoken on Ternate, a small island in the eastern Indonesian province of Maluku Utara (see Maps 1-2). Ternate has been famous as an important centre in the spice trade, particularly that of cloves, since in this region cloves originally grow. For centuries traders from all over the world came here to get their share in this profitable trade (see Andaya 1993). Malay was used as a lingua franca between the traders and the local population as well as amongst the traders themselves who had different linguistic backgrounds. -

Languages of Indonesia (Sulawesi)

Ethnologue report for Indonesia (Sulawesi) Page 1 of 27 Languages of Indonesia (Sulawesi) See language map. Indonesia (Sulawesi). 14,111,444 (2000 census). 4 provinces. Information mainly from T. Sebeok 1971; J. C. Anceaux 1978; S. Kaseng 1978, ms. (1983); B. H. Bhurhanuddin ms. (1979); J. N. Sneddon 1983, 1989, 1993; C. E. and B. D. Grimes 1987; T. Friberg 1987; T. Friberg and T. Laskowske 1988; R. van den Berg 1988, 1996; M. Martens 1989; N. P. Himmelmann 1990; R. Blust 1991; Noorduyn 1991a; D. E. Mead 1998. The number of languages listed for Indonesia (Sulawesi) is 114. Of those, all are living languages. Living languages Andio [bzb] 1,700 (1991 SIL). Central Sulawesi, Banggai District, Lamala Subdistrict, eastern peninsula, Taugi and Tangeban villages. Alternate names: Masama, Andio'o, Imbao'o. Dialects: Related to Balantak, Saluan. Lexical similarity 44% with Bobongko, 62% with Coastal Saluan, 66% with Balantak. Classification: Austronesian, Malayo- Polynesian, Sulawesi, Saluan-Banggai, Western More information. Aralle- [atq] 12,000 (1984 SIL). South Sulawesi, Tabulahan Mambi Subdistrict, between Mandar and Kalumpang. Dialects: Aralle, Tabulahan, Mambi. Aralle has 84% to 89% lexical similarity with other dialects listed, 75% to 80% with dialects of Pitu Ulunna Salu, Pannei, Ulumandak. Classification: Austronesian, Malayo-Polynesian, Sulawesi, South Sulawesi, Northern, Pitu Ulunna Salu More information. Bada [bhz] 10,000 (1991 SIL). South central portion of central Sulawesi, in 14 villages of Lore Selatan Subdistrict, two mixed villages of Pamona Selatan Subdistrict, four mixed villages of Poso Pesisir Subdistrict, part of Lemusa village in Parigi Subdistrict, and Ampibabo Subdistrict. Ako village is in northern Mamuju District, Pasangkayu Subdistrict.