Exploring Magical History: Egypt – II Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom by Josephine Mccarthy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Was the Function of the Earliest Writing in Egypt Utilitarian Or Ceremonial? Does the Surviving Evidence Reflect the Reality?”

“Was the function of the earliest writing in Egypt utilitarian or ceremonial? Does the surviving evidence reflect the reality?” Article written by Marsia Sfakianou Chronology of Predynastic period, Thinite period and Old Kingdom..........................2 How writing began.........................................................................................................4 Scopes of early Egyptian writing...................................................................................6 Ceremonial or utilitarian? ..............................................................................................7 The surviving evidence of early Egyptian writing.........................................................9 Bibliography/ references..............................................................................................23 Links ............................................................................................................................23 Album of web illustrations...........................................................................................24 1 Map of Egypt. Late Predynastic Period-Early Dynastic (Grimal, 1994) Chronology of Predynastic period, Thinite period and Old Kingdom (from the appendix of Grimal’s book, 1994, p 389) 4500-3150 BC Predynastic period. 4500-4000 BC Badarian period 4000-3500 BC Naqada I (Amratian) 3500-3300 BC Naqada II (Gerzean A) 3300-3150 BC Naqada III (Gerzean B) 3150-2700 BC Thinite period 3150-2925 BC Dynasty 1 3150-2925 BC Narmer, Menes 3125-3100 BC Aha 3100-3055 BC -

Reading G Uide

1 Reading Guide Introduction Pharaonic Lives (most items are on map on page 10) Bodies of Water Major Regions Royal Cities Gulf of Suez Faiyum Oasis Akhetaten Sea The Levant Alexandria Nile River Libya Avaris Nile cataracts* Lower Egypt Giza Nile Delta Nubia Herakleopolis Magna Red Sea Palestine Hierakonpolis Punt Kerma *Cataracts shown as lines Sinai Memphis across Nile River Syria Sais Upper Egypt Tanis Thebes 2 Chapter 1 Pharaonic Kingship: Evolution & Ideology Myths Time Periods Significant Artifacts Predynastic Origins of Kingship: Naqada Naqada I The Narmer Palette Period Naqada II The Scorpion Macehead Writing History of Maqada III Pharaohs Old Kingdom Significant Buildings Ideology & Insignia of Middle Kingdom Kingship New Kingdom Tombs at Abydos King’s Divinity Mythology Royal Insignia Royal Names & Titles The Book of the Heavenly Atef Crown The Birth Name Cow Blue Crown (Khepresh) The Golden Horus Name The Contending of Horus Diadem (Seshed) The Horus Name & Seth Double Crown (Pa- The Nesu-Bity Name Death & Resurrection of Sekhemty) The Two Ladies Name Osiris Nemes Headdress Red Crown (Desheret) Hem Deities White Crown (Hedjet) Per-aa (The Great House) The Son of Re Horus Bull’s tail Isis Crook Osiris False beard Maat Flail Nut Rearing cobra (uraeus) Re Seth Vocabulary Divine Forces demi-god heka (divine magic) Good God (netjer netjer) hu (divine utterance) Great God (netjer aa) isfet (chaos) ka-spirit (divine energy) maat (divine order) Other Topics Ramesses II making sia (Divine knowledge) an offering to Ra Kings’ power -

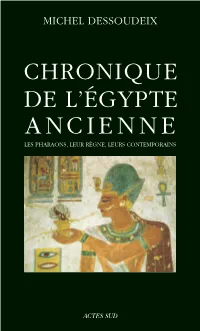

Chronique De L'egypte Ancienne

OK Chronique égypte ancienne 21/03/08 12:07 Page 1 Riche de ses trois mille ans d’histoire, l’Égypte pharaonique a vu se suc- MICHEL DESSOUDEIX céder quelque trois cent quarante-cinq souverains. Si certains sont pas- MICHEL DESSOUDEIX sés à la postérité, notamment les rois des périodes prospères – les trois grands Empires –, d’autres ne sont plus que de simples noms pour les archéologues. Les époques troublées – dites Périodes Intermédiaires – CHRONIQUE compliquent la tâche des scientifiques dans la reconstitution de la DE L’ÉGYPTE chronologie royale. Ce livre, qui représente avant tout un outil didactique, fournit un ANCIENNE état des lieux des connaissances actuelles, en regroupant tous les rensei- LES PHARAONS, LEUR RÈGNE, gnements fondamentaux sur chacun des pharaons attestés. Ceux-ci LEURS CONTEMPORAINS CHRONIQUE sont présentés de manière systématique, sous forme de fiche incluant : dates d’intronisation et de mort, famille (parents, épouses et enfants), lieu de sépulture, événements marquants du règne, sites où le pharaon a mené une activité architecturale, titulature complète, contemporains du règne accompagnés de leurs titres, bibliographie. Suivent des DE L’ÉGYPTE tableaux donnant la possibilité de retrouver un roi à partir d’un élé- ment de sa titulature et, pour aller directement à l’information recher- chée, des index croisés recoupant les données intégrées dans l’ensemble des fiches. Cette étude ne serait pas complète sans une liste des nomes ANCIENNE – les divisions administratives de l’Egypte – avec leur nom en hiérogly- phes, une liste des principales villes classées en fonction de ces nomes, LES PHARAONS, LEUR RÈGNE, LEURS CONTEMPORAINS en tenant compte de leur évolution dans le temps, et un ensemble de cartes permettant de situer rapidement les divers éléments utilisés dans le corps de l’ouvrage. -

Des Égyptiens Portant Un Baudrier Libyen ? Jennifer Romion

Institut d’égyptologie François Daumas UMR 5140 « Archéologie des Sociétés Méditerranéennes » Cnrs – Université Paul Valéry (Montpellier III) Des Égyptiens portant un baudrier libyen ? Jennifer Romion Citer cet article : J. Romion, « Des Égyptiens portant un baudrier libyen ? », ENIM 4, 2011, p. 91-102. ENiM – Une revue d’égyptologie sur internet est librement téléchargeable depuis le site internet de l’équipe « Égypte nilotique et méditerranéenne » de l’UMR 5140, « Archéologie des sociétés méditerranéennes » : http://recherche.univ-montp3.fr/egyptologie/enim/ Des Égyptiens portant un baudrier libyen ? Jennifer Romion Institut d’égyptologie François Daumas UMR 5140 (CNRS - Université Paul-Valéry - Montpellier III) ÉTUDE MÊME succincte des textes et des reliefs égyptiens montre que bien des traditions pharaoniques sont héritées de contacts avec les cultures voisines. On peut L’bien sûr mentionner l’utilisation du char et du cheval, innovation due à la présence des Hyksôs lors de la Deuxième Période intermédiaire. Le domaine des textiles ne fait pas exception et les Textes des Pyramides apparaissent comme une source privilégiée pour l’étude de ces premiers emprunts. Citons en premier lieu les vêtements j©“, b“, ≈sƒƒ 1 et swÌ, sortes de manteaux ou de capes dont le modèle commun à l’ensemble des civilisations du Proche- Orient ancien est étroitement associé par les Égyptiens aux étrangers venus de l’est comme de l’ouest. Les formules funéraires mentionnent aussi un devanteau ‡sm.t, ornement caractéristique du dieu Sopdou, seigneur des marges désertiques orientales, dont le roi se pare lorsqu’il parcourt « son pays tout entier » 2. Un habit doit encore être cité en exemple. -

Origins5-Programme.Pdf

Origins5 © Béatrix Midant-Reynes and Yann Tristant 2014, on behalf of The Fifth International Conference of Predynastic and Early Dynastic studies Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, Cairo Fifth international conference of Predynastic and Early Dynastic Studies Origins5 | Cairo, 13-18 April 2014 Organised by the Institut français d’archéologie orientale (IFAO) in cooperation with the Ministry of State for Antiquities (MSA) and the Institut Français d’Égypte (IFE) Presentation The fifth international conference of Predynastic and Early Dynastic Studies marks the continuation of the previous successful conferences which happens every three years: Kraków 2002, Toulouse 2005, London 2008 and New York 2011. This five-day international event will gather in Cairo a network of experts from different countries. They will present and discuss their respective research relating a significant range of themes within the broader subject of the origins of the Egyptian State (from the Predynastic period to the beginning of the Old Kingdom). This Fifth international conference marks a new stage in the momentum acquired by Predynastic and Early Dynastic studies. Topics Topics developed during the conference concern all aspects of Predynastic and Early Dynastic Egypt. Papers and posters will be organised around the following themes: 4Craft specialisation, technology and material culture 4Upper-Lower Egypt interactions 4Deserts-Nile Valley interactions 4Egypt and its neighbours (Levant, Nubia, Sahara) 4Birth of writing 4Absolute and relative chronology 4Cult, ideology and social complexity 4Results of recent fieldwork 3 COMMITTEES Organisation Committee Béatrix Midant-Reynes, Institut français d’archéologie orientale, Cairo, Egypt Yann Tristant, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia Scientific Committee Matthew DouglasAdams , Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, New York, USA Nathalie Buchez, INRAP, Amiens/TRACES-UMR 5608, CNRS, Toulouse, France Krzysztof M. -

UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology

UCLA UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology Title Mace Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/497168cs Journal UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 1(1) Author Stevenson, Alice Publication Date 2008-09-15 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California MACE الصولجان Alice Stevenson EDITORS WILLEKE WENDRICH Editor-in-Chief Area Editor Material Culture, Art, and Architecture University of California, Los Angeles JACCO DIELEMAN Editor University of California, Los Angeles ELIZABETH FROOD Editor University of Oxford JOHN BAINES Senior Editorial Consultant University of Oxford Short Citation: Stevenson, 2008, Mace. UEE. Full Citation: Stevenson, Alice, 2008, Mace. In Willeke Wendrich (ed.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, Los Angeles, http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz000sn03x 1070 Version 1, September 2008 http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz000sn03x MACE الصولجان Alice Stevenson Keule Massue The mace, a club-like weapon attested in ancient Egypt from the Predynastic Period onward, played both functional and ceremonial roles, although more strongly the latter. By the First Dynasty it had become intimately associated with the power of the king, and the archetypal scene of the pharaoh wielding a mace endured from this time on in temple iconography until the Roman Period. الصولجان ‘ سﻻح يشبه عصا غليظة عند طرفھا ‘ كان معروفاً فى مصر القديمة منذ عصر ما قبل اﻷسرات ولعب أحياناً دوراً وظيفياً وغالباً دوراً تشريفياً فى المراسم. في عصر اﻷسرة اﻷولى اصبح مرتبطاً على ٍنحو حميم بقوة الملك والنموذج اﻷصلي لمشھد الفرعون ممسك بالصولجان بدأ آنذاك بالمعابد وإستمر حتى العصر الروماني. he mace is a club-like weapon with that became prevalent in dynastic Egypt. -

Cwiek, Andrzej. Relief Decoration in the Royal

Andrzej Ćwiek RELIEF DECORATION IN THE ROYAL FUNERARY COMPLEXES OF THE OLD KINGDOM STUDIES IN THE DEVELOPMENT, SCENE CONTENT AND ICONOGRAPHY PhD THESIS WRITTEN UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. KAROL MYŚLIWIEC INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY FACULTY OF HISTORY WARSAW UNIVERSITY 2003 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work would have never appeared without help, support, advice and kindness of many people. I would like to express my sincerest thanks to: Professor Karol Myśliwiec, the supervisor of this thesis, for his incredible patience. Professor Zbigniew Szafrański, my first teacher of Egyptian archaeology and subsequently my boss at Deir el-Bahari, colleague and friend. It was his attitude towards science that influenced my decision to become an Egyptologist. Professor Lech Krzyżaniak, who offered to me really enormous possibilities of work in Poznań and helped me to survive during difficult years. It is due to him I have finished my thesis at last; he asked me about it every time he saw me. Professor Dietrich Wildung who encouraged me and kindly opened for me the inventories and photographic archives of the Ägyptisches Museum und Papyrussammlung, and Dr. Karla Kroeper who enabled my work in Berlin in perfect conditions. Professors and colleagues who offered to me their knowledge, unpublished material, and helped me in various ways. Many scholars contributed to this work, sometimes unconsciously, and I owe to them much, albeit all the mistakes and misinterpretations are certainly by myself. Let me list them in an alphabetical order, pleno titulo: Hartwig -

Before the Pyramids Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu Before the pyramids oi.uchicago.edu before the pyramids baked clay, squat, round-bottomed, ledge rim jar. 12.3 x 14.9 cm. Naqada iiC. oim e26239 (photo by anna ressman) 2 oi.uchicago.edu Before the pyramids the origins of egyptian civilization edited by emily teeter oriental institute museum puBlications 33 the oriental institute of the university of chicago oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Control Number: 2011922920 ISBN-10: 1-885923-82-1 ISBN-13: 978-1-885923-82-0 © 2011 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2011. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago This volume has been published in conjunction with the exhibition Before the Pyramids: The Origins of Egyptian Civilization March 28–December 31, 2011 Oriental Institute Museum Publications 33 Series Editors Leslie Schramer and Thomas G. Urban Rebecca Cain and Michael Lavoie assisted in the production of this volume. Published by The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago 1155 East 58th Street Chicago, Illinois 60637 USA oi.uchicago.edu For Tom and Linda Illustration Credits Front cover illustration: Painted vessel (Catalog No. 2). Cover design by Brian Zimerle Catalog Nos. 1–79, 82–129: Photos by Anna Ressman Catalog Nos. 80–81: Courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford Printed by M&G Graphics, Chicago, Illinois. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Service — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984 ∞ oi.uchicago.edu book title TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword. Gil J. -

Early Dynastic Egypt

EARLY DYNASTIC EGYPT EARLY DYNASTIC EGYPT Toby A.H.Wilkinson London and New York First published 1999 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. © 1999 Toby A.H.Wilkinson All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data Wilkinson, Toby A.H. Early Dynastic Egypt/Toby A.H.Wilkinson p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p.378) and index. 1. Egypt—History—To 332 B.C. I. Title DT85.W49 1999 932′.012–dc21 98–35836 CIP ISBN 0-203-02438-9 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-20421-2 (Adobe e-Reader Format) ISBN 0-415-18633-1 (Print Edition) For Benjamin CONTENTS List of plates ix List of figures x Prologue xii Acknowledgements xvii PART I INTRODUCTION 1 Egyptology and the Early Dynastic Period 2 2 Birth of a Nation State 23 3 Historical Outline 50 PART II THE ESTABLISHMENT OF AUTHORITY 4 Administration 92 5 Foreign Relations 127 6 Kingship 155 7 Royal Mortuary Architecture 198 8 Cults and -

Mostafa Elshamy © 2015 All Rights Reserved

Ancient Egypt: The Primal Age of Divine Revelation Volume I: Genesis Revised Edition A Research by: Mostafa Elshamy © 2015 All Rights Reserved Library of Congress United States Copyright Office Registration Number TXu 1-932-870 Author: Mostafa Elshamy Copyright Claimant and Certification: Mostafa Elshamy This volume, coinciding with momentous happenings in Egypt, is dedicated to: Al-Sisi: Horus of Truth and Lord of the Two Lands and The Egyptians who are writing an unprecedented chapter in the modern history of humanity Table of Contents Introduction ………………………………………………………………………. i-ii Chapter I Our Knowledge of the Ancient Egyptian Thoughts of the Spiritual Constituents of Man ……………………………………… 1 Chapter II The Doctrine of the Spirit …………………………………………. 16 - Texts embracing the Breath of Life ………………………………. 16 - Texts comprising Breathing Nostrils ……………………………… 18 - Texts substantiating Lifetime ……………………………………… 19 - The Breath of life: as a Metaphor ……………………………….. 20 - A Long-term Perplexity …………………………………………… 25 - The Tripartite Nature of Human ………………………………….. 27 - The Genuine Book of Genesis of Man …………………………..... 28 - Neith: the Holy Spirit ……………………………………………… 29 - Seshat and the Shen ……………………………………………….. 37 - The Egyptian Conception of "Sahu" ……………………………… 43 - Isolating the hieroglyph of Spirit ………………………………..... 49 Chapter III The Doctrine of the Soul ……………………………………………. 50 - The Louvre Palette ………………………………………………… 54 - The Oxford Palette ………………………………………………… 57 - The Hunters Palette ………………………………………………... 58 - The Battlefield Palette ……………………………………………. -

EXPERIENCING POWER, GENERATING AUTHORITY Cosmos, Politics, and the Ideology of Kingship in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia

EXPERIENCING POWER, GENERATING AUTHORITY Cosmos, Politics, and the Ideology of Kingship in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia edited by Jane A. Hill, Philip Jones, and Antonio J. Morales University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology Philadelphia Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data © 2013 by the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology Philadelphia, PA All rights reserved. Published 2013 Published for the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology by the University of Pennsylvania Press. Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. 1 Propaganda and Performance at the Dawn of the State ellen f. morris ccording to pharaonic ideology, the maintenance of cosmic, political, Aand natural order was unthinkable without the king, who served as the crucial lynchpin that held together not only Upper and Lower Egypt, but also the disparate worlds of gods and men. Because of his efforts, soci- ety functioned smoothly and the Nile floods brought forth abundance. This ideology, held as gospel for millennia, was concocted. The king had no su- pernatural power to influence the Nile’s flood and the institution of divine kingship was made to be able to function with only a child or a senile old man at its helm. This chapter focuses on five foundational tenets of phara- onic ideology, observable in the earliest monuments of protodynastic kings, and examines how these tenets were transformed into accepted truths via the power of repeated theatrical performance. Careful choreography and stagecraft drew upon scent, pose, metaphor, abject foils, and numerous other ploys to naturalize a political order that had nothing natural about it. -

The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms

McDONALD INSTITUTE CONVERSATIONS The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms Edited by Norman Yoffee The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms McDONALD INSTITUTE CONVERSATIONS The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms Edited by Norman Yoffee with contributions from Tom D. Dillehay, Li Min, Patricia A. McAnany, Ellen Morris, Timothy R. Pauketat, Cameron A. Petrie, Peter Robertshaw, Andrea Seri, Miriam T. Stark, Steven A. Wernke & Norman Yoffee Published by: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research University of Cambridge Downing Street Cambridge, UK CB2 3ER (0)(1223) 339327 [email protected] www.mcdonald.cam.ac.uk McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2019 © 2019 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. The Evolution of Fragility: Setting the Terms is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 (International) Licence: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ISBN: 978-1-902937-88-5 Cover design by Dora Kemp and Ben Plumridge. Typesetting and layout by Ben Plumridge. Cover image: Ta Prohm temple, Angkor. Photo: Dr Charlotte Minh Ha Pham. Used by permission. Edited for the Institute by James Barrett (Series Editor). Contents Contributors vii Figures viii Tables ix Acknowledgements x Chapter 1 Introducing the Conference: There Are No Innocent Terms 1 Norman Yoffee Mapping the chapters 3 The challenges of fragility 6 Chapter 2 Fragility of Vulnerable Social Institutions in Andean States 9 Tom D. Dillehay & Steven A. Wernke Vulnerability and the fragile state