Protection of Civilians in Mosul: Identifying Lessons for Contingency Planning a Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) and Interaction Roundtable October 17, 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Resurgence of Asa'ib Ahl Al-Haq

December 2012 Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ Photo Credit: Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq protest in Kadhimiya, Baghdad, September 2012. Photo posted on Twitter by Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. ©2012 by the Institute for the Study of War. Published in 2012 in the United States of America by the Institute for the Study of War. 1400 16th Street NW, Suite 515 Washington, DC 20036. http://www.understandingwar.org Sam Wyer MIDDLE EAST SECURITY REPORT 7 THE RESURGENCE OF ASA’IB AHL AL-HAQ ABOUT THE AUTHOR Sam Wyer is a Research Analyst at the Institute for the Study of War, where he focuses on Iraqi security and political matters. Prior to joining ISW, he worked as a Research Intern at AEI’s Critical Threats Project where he researched Iraqi Shi’a militia groups and Iranian proxy strategy. He holds a Bachelor’s Degree in Political Science from Middlebury College in Vermont and studied Arabic at Middlebury’s school in Alexandria, Egypt. ABOUT THE INSTITUTE The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) is a non-partisan, non-profit, public policy research organization. ISW advances an informed understanding of military affairs through reliable research, trusted analysis, and innovative education. ISW is committed to improving the nation’s ability to execute military operations and respond to emerging threats in order to achieve U.S. -

A New Formula in the Battle for Fallujah | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds A New Formula in the Battle for Fallujah by Michael Knights May 25, 2016 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Michael Knights Michael Knights is the Boston-based Jill and Jay Bernstein Fellow of The Washington Institute, specializing in the military and security affairs of Iraq, Iran, and the Persian Gulf states. Articles & Testimony The campaign is Iraq's latest attempt to push militia and coalition forces into a single battlespace, and lessons from past efforts have seemingly improved their tactics. n May 22, the Iraqi government announced the opening of the long-awaited battle of Fallujah, the city only O 30 miles west of Baghdad that has been fully under the control of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant group for the past 29 months. Fallujah was a critical hub for al-Qaeda in Iraq and later ISIL in the decade before ISIL's January 2014 takeover. On the one hand it may seem surprising that Fallujah has not been liberated sooner -- after all, it has been the ISIL- controlled city closest to Baghdad for more than two years. The initial reason was that there was always something more urgent to do with Iraq's security forces. In January 2014, the Iraqi security forces were focused on preventing an ISIL takeover of Ramadi next door. The effort to retake Fallujah was judged to require detailed planning, and a hasty counterattack seemed like a pointless risk. In retrospect it may have been worth an early attempt to break up ISIL's control of the city while it was still incomplete. -

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq

The Politics of Security in Ninewa: Preventing an ISIS Resurgence in Northern Iraq Julie Ahn—Maeve Campbell—Pete Knoetgen Client: Office of Iraq Affairs, U.S. Department of State Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Advisor: Meghan O’Sullivan Policy Analysis Exercise Seminar Leader: Matthew Bunn May 7, 2018 This Policy Analysis Exercise reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing the views of the US Government, nor those of Harvard University or any of its faculty. Acknowledgements We would like to express our gratitude to the many people who helped us throughout the development, research, and drafting of this report. Our field work in Iraq would not have been possible without the help of Sherzad Khidhir. His willingness to connect us with in-country stakeholders significantly contributed to the breadth of our interviews. Those interviews were made possible by our fantastic translators, Lezan, Ehsan, and Younis, who ensured that we could capture critical information and the nuance of discussions. We also greatly appreciated the willingness of U.S. State Department officials, the soldiers of Operation Inherent Resolve, and our many other interview participants to provide us with their time and insights. Thanks to their assistance, we were able to gain a better grasp of this immensely complex topic. Throughout our research, we benefitted from consultations with numerous Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) faculty, as well as with individuals from the larger Harvard community. We would especially like to thank Harvard Business School Professor Kristin Fabbe and Razzaq al-Saiedi from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative who both provided critical support to our project. -

Policy Brief on Civilian Protection in the Current Mosul Campaign

Policy Brief on Civilian Protection in the Current Mosul Campaign February 2017 DISPLACEMENT ROUTES 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Protection Concerns in Mosul ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Iraqi Security Forces in Mosul ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Coalition Operations Targeting the Islamic State ................................................................................................. 7 Proactive Protection Efforts ......................................................................................................................................... 9 Screening of Civilians .................................................................................................................................................... 11 Train and Advise Mission ............................................................................................................................................. 11 Oversight of Pro-Government Forces ..................................................................................................................... 12 Stabilization Efforts and Rebuilding Trust with Civilians ................................................................................... -

Call for Proposal

CALL FOR PROPOSAL Ref. No.: CFP/IRQ/2019-005 < Construction of a Potable Water Network and organization of a Garbage Collection Campaign in the informal settlement Al-Qibla in Basra City, Basra Governorate > Purpose of CFP: Improving living conditions in the targeted informal settlement through infrastructure upgrading and solid waste collection, with an emphasis on providing on-the-job training and local employment, in addition to the mobilization of community members to conduct environmental initiatives through cash for work. Submission Start Date: 24 Apr 2019 Submission Deadline Date and time: 08 May 2019, at 3 pm Key Project Information UN-Habitat Project title: Construction of a Potable Water Network and organization of a Garbage collection campaign in the informal settlement of Al-Qibla in Basra City, Basra Governorate Locations: Town/City: Al Qibla in Basra City, Basra Governorate Country: Iraq Anticipated start date: 26 May 2019 Estimated duration of project in calendar months: 33 days Maximum proposed value in US$: US$ 180,000 Lead Organizations Unit : UN-Habitat-Iraq Page 1 of 7 A. Brief Background of the Project In late 2014, UN-Habitat launched a comprehensive ‘National Informal Settlements Program’ comprising of institutional, legal, financial and technical pillars to carry out thorough diagnostic of the existing urban informal areas, and to identify appropriate technical planning solutions for their regularization and upgrading. Efforts focused on conducting an intensive review of the available financial mechanisms and the development of a Roadmap (endorsed by the Cabinet’s resolution No. 279 of 2015) that provides the strategic directions of the national programme and securing policy support within the Government of Iraq (GoI) through an appropriate institutional setup, followed by mapping and analysis of informal settlements in Iraq. -

WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What Will It Take to Stop the Carnage?

Winners of the Overseas Press Club Awards 2017 Annual Edition DATELINE WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What will it take to stop the carnage? DATELINE 2017 1 President’s Letter / dEIdRE dEPkE here is a theme to our gathering tonight at the 78th entries, narrowing them to our 22 winners. Our judging process was annual Overseas Press Club Gala, and it’s not an easy one. ably led by Scott Kraft of the Los Our work as journalists across the globe is under Angeles Times. Sarah Lubman headed our din- unprecedented and frightening attack. Since the conflict in ner committee, setting new records TSyria began in 2011, 107 journalists there have been killed, according the for participation. She was support- Committee to Protect Journalists. That’s more members of the press corps ed by Bill Holstein, past president of the OPC and current head of to die than were lost during 20 years of war in Vietnam. In the past year, the OPC Foundation’s board, and our colleagues also have been fatally targeted in Iraq, Yemen and Ukraine. assisted by her Brunswick colleague Beatriz Garcia. Since 2013, the Islamic State has captured or killed 11 journalists. Almost This outstanding issue of Date- 300 reporters, editors and photographers are being illegally detained by line was edited by Michael Serrill, a past president of the OPC. Vera governments around the world, with at least 81 journalists imprisoned Naughton is the designer (she also in Turkey alone. And at home, we have been labeled the “enemy of the recently updated the OPC logo). -

Poverty Rates

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Mapping Poverty inIraq Mapping Poverty Where are Iraq’s Poor: Poor: Iraq’s are Where Acknowledgements This work was led by Tara Vishwanath (Lead Economist, GPVDR) with a core team comprising Dhiraj Sharma (ETC, GPVDR), Nandini Krishnan (Senior Economist, GPVDR), and Brian Blankespoor (Environment Specialist, DECCT). We are grateful to Dr. Mehdi Al-Alak (Chair of the Poverty Reduction Strategy High Committee and Deputy Minister of Planning), Ms. Najla Ali Murad (Executive General Manager of the Poverty Reduction Strategy), Mr. Serwan Mohamed (Director, KRSO), and Mr. Qusay Raoof Abdulfatah (Liv- ing Conditions Statistics Director, CSO) for their commitment and dedication to the project. We also acknowledge the contribution on the draft report of the members of Poverty Technical High Committee of the Government of Iraq, representatives from academic institutions, the Ministry of Planning, Education and Social Affairs, and colleagues from the Central Statistics Office and the Kurdistan Region Statistics during the Beirut workshop in October 2014. We are thankful to our peer reviewers - Kenneth Simler (Senior Economist, GPVDR) and Nobuo Yoshida (Senior Economist, GPVDR) – for their valuable comments. Finally, we acknowledge the support of TACBF Trust Fund for financing a significant part of the work and the support and encouragement of Ferid Belhaj (Country Director, MNC02), Robert Bou Jaoude (Country Manager, MNCIQ), and Pilar -

Factors Affecting Stability in Northern Iraq

AUGUST 2009 . VOL 2 . ISSUE 8 Factors Affecting Stability government by demonstrating that they the city the “strategic center of gravity” hold a grim likelihood for success is for AQI.8 Months later, in a new in Northern Iraq less credible absent U.S. forces. For this Mosul offensive directly commanded reason, insurgents are testing the ISF on by al-Maliki called “Lion’s Roar,” the By Ramzy Mardini its capability, resolve, and credibility as lack of resistance among insurgents a fair and non-sectarian institution. disappointed some commanders who iraq entered a new security were expecting a decisive Alamo-style environment after June 30, 2009, This litmus test is most likely to battle.9 when U.S. combat forces exited Iraqi occur in Mosul, the capital of Ninawa cities in accordance with the first of Province. In its current political and Today, AQI and affiliated terrorist two withdrawal deadlines stipulated security context, the city is best situated groups, such as the Islamic State of Iraq, in the Status of Forces Agreement for insurgents to make early gains in still possess a strategic and operational (SOFA). Signed in December 2008 by propagating momentum. Geographically capacity to wage daily attacks in Mosul.10 President George W. Bush and Iraqi located 250 miles north of Baghdad Although the daily frequency of attacks Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki, the along the Tigris River, Mosul is Iraq’s in Mosul dropped slightly from 2.43 SOFA concedes that December 31, 2011 second largest city with a population attacks in June 2009 to 2.35 attacks in will be the deadline for the complete of 1.8 million.2 Described as an ethnic July 2009, the corresponding monthly withdrawal of U.S. -

Fighting the Islamic State By, With, and Through How Mattered As Much As What

Paratroopers with Charlie Battery, 2nd Battalion, 319th Airborne Field Artillery Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division, rotate M777 155mm howitzer in preparation to engage militants with artillery fire in support of Iraqi and Peshmerga fighters in Mosul (U.S. Army/Christopher Bigelow) Fighting the Islamic State By, With, and Through How Mattered as Much as What By J. Patrick Work n January 2017, the 2nd Brigade a simple framework: help the ISF and and approach—how we advised—offer Combat Team, 82nd Airborne Divi- hurt IS every day. Naturally, we had useful examples and angles for leaders I sion, deployed to bolster the Iraqi missteps, but our team also served ISF to ponder as we consider future excur- Security Forces (ISF) in the campaign and coalition commanders well on sions with this style of high-intensity to annihilate the so-called Islamic some terribly uncertain days. Specifi- security force assistance.1 State (IS). Task Force Falcon joined cally, how we advised ISF commanders the coalition advise-and-assist (A&A) was as important as what we advised Organizing Principles effort with 2 weeks remaining during them to do in order to win. We mixed Our mission under Operation Inherent the 100-day offensive to retake east innovative concepts and straightfor- Resolve (OIR) proved infinitely different Mosul. For the next 8 months, we ward tactics to attack IS by, with, and than the exhausting, firsthand combat wrestled a complex environment with through the ISF, yet the entire effort that many of us experienced in Iraq always centered on our partners’ lead- from 2003 to 2008. -

ISIS Battle Plan for Baghdad

Jessica D. Lewis BACKGROUNDER June 27, 2014 ISIS BattlE PlAn FoR BAgHdAd here are indications that ISIS is about to launch into a new offensive in Iraq. ISIS published photos of Ta military parade through the streets of Mosul on June 24, 2014 showcasing U.S. military equipment, including armored vehicles and towed artillery systems.1 ISIS reportedly executed another parade in Hawijah on June 26, 2014.2 These parades may be a demonstration of force to reinforce their control of these urban centers. They may also be a prelude to ISIS troop movements, and it is important to anticipate where ISIS may deploy these forces forward. Meanwhile, ISIS also renewed the use of suicide bombers in the vicinity of Baghdad. An ISIS bomber with a suicide vest (SVEST) attacked the Kadhimiya shrine in northern Baghdad on June 26, 2014,3 one of the four holy sites in Iraq that Iran and Shi’a militias are most concerned to protect. ISIS also incorporated an SVEST into a complex attack in Mahmudiyah, south of Baghdad, on June 25, 2014 in a zone primarily controlled by the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) and Shi’a militias on the road from Baghdad to Karbala.4 These attacks are demonstrations that ISIS has uncommitted forces in the Baghdad Belts that may be brought to bear in new offensives. ISIS’s offensive has not culminated, and the ISIS campaign for Iraq is not over. Rather, as Ramadan approaches, their main offensive is likely imminent.* The Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) is formidable, of former Saddam-era military officers who know the military but it is also predictable. -

Geopolitical Overview of Conflicts 2016

Geopolitical overview of Spanish Institute for conflicts 2016 Strategic Studies MINISTERIO DE DEFENSA Geopolitical overview Spanish Institute for of conflicts 2016 Strategic Studies MINISTERIO DE DEFENSA SPANISH OFFICIAL PUBLICATIONS CATALOGUE http://publicacionesoficiales.boe.es Edita: SECRETARÍA GENERAL TÉCNICA http://publicaciones.defensa.gob.es/ © Author and Publisher, 2017 NIPO: 083-16-308-8 (print on demand) NIPO: 083-16-309-3 (e-book edition) Publication date: september 2017 The authors are solely responsible for the opinions expresed in the articles in this publication. The exploitation righits of this work are protected by the Spanish Intellectual Property Act. No parts of this publication may be produced, stored or transmitted in any way nor by any means, electronic, mechanical or print, including photo- copies or any other means without prior, express, written consent of the © copyright holders. ÍNDEX Page Introduction The role of the major powers in current conflicts ...................................................... 9 Miguel Ángel Ballesteros Martín Conflict trends ............................................................................................................................... 9 The resolutions of the Security Council as a gauge of its activity ...................................... 11 Russia’s comeback as a world power ...................................................................................... 13 The military policy of China as an emerging power ............................................................. -

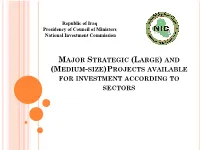

Major Strategic Projects Available for Investment According to Sectors

Republic of Iraq Presidency of Council of Ministers National Investment Commission MAJOR STRATEGIC (LARGE) AND (MEDIUM-SIZE)PROJECTS AVAILABLE FOR INVESTMENT ACCORDING TO SECTORS NUMBER OF INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES ACCORDING TO SECTORS No. Sector Number of oppurtinites Major strategic projects 1. Chemicals, Petrochemicals, Fertilizers and 18 Refinery sector 2 Transportation Sector including (airports/ 16 railways/highways/metro/ports) 3 Special Economic Zones 4 4 Housing Sector 3 Medium-size projects 5 Engineering and Construction Industries Sector 6 6 Commercial Sector 12 7 tourism and recreational Sector 2 8 Health and Education Sector 10 9 Agricultural Sector 86 Total number of opportunities 157 Major strategic projects 1. CHEMICALS, PETROCHEMICALS, FERTILIZERS AND REFINERY SECTOR: A. Rehabilitation of existing fertilizer plant in Baiji and the implementation of new production lines (for export). • Production of 500 ton of Urea fertilizer • Expected capital: 0.5 billion USD • Return on Investment rate: %17 • The plant is operated by LPG supplied by the North Co. in Kirkuk Province. 9 MW Generators are available to provide electricity for operation. • The ministry stopped operating the plant on 1/1/2014 due to difficult circumstances in Saladin Province. • The plant has1165 workers • About %60 of the plant is damaged. Reconstruction and development of fertilizer plant in Abu Al Khaseeb (for export). • Plant history • The plant consist of two production lines, the old production line produced Urea granules 200 t/d in addition to Sulfuric Acid and Ammonium Phosphate. This plant was completely destroyed during the war in the eighties. The second plant was established in 1973 and completed in 1976, designed to produce Urea fertilizer 420 thousand metric ton/y.