NO ONE KNOWS ABOUT US by Bridget Canning. a Creative Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

The Rights of War and Peace Book I

the rights of war and peace book i natural law and enlightenment classics Knud Haakonssen General Editor Hugo Grotius uuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuu ii ii ii iinatural law and iienlightenment classics ii ii ii ii ii iiThe Rights of ii iiWar and Peace ii iibook i ii ii iiHugo Grotius ii ii ii iiEdited and with an Introduction by iiRichard Tuck ii iiFrom the edition by Jean Barbeyrac ii ii iiMajor Legal and Political Works of Hugo Grotius ii ii ii ii ii ii iiliberty fund ii iiIndianapolis ii uuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuuu This book is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a foundation established to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. The cuneiform inscription that serves as our logo and as the design motif for our endpapers is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 b.c. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash. ᭧ 2005 Liberty Fund, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 09 08 07 06 05 c 54321 09 08 07 06 05 p 54321 Frontispiece: Portrait of Hugo de Groot by Michiel van Mierevelt, 1608; oil on panel; collection of Historical Museum Rotterdam, on loan from the Van der Mandele Stichting. Reproduced by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Grotius, Hugo, 1583–1645. [De jure belli ac pacis libri tres. English] The rights of war and peace/Hugo Grotius; edited and with an introduction by Richard Tuck. p. cm.—(Natural law and enlightenment classics) “Major legal and political works of Hugo Grotius”—T.p., v. -

NITROGEN on MARS: INSIGHTS from CURIOSITY. J. C. Stern1 , B. Sutter2, W. A. Jackson3, Rafael Na- Varro-González4, Christopher P

Lunar and Planetary Science XLVIII (2017) 2726.pdf 1 2 3 NITROGEN ON MARS: INSIGHTS FROM CURIOSITY. J. C. Stern , B. Sutter , W. A. Jackson , Rafael Na- varro-González4, Christopher P. McKay5, Douglas W. Ming6, P. Douglas Archer2, D. P. Glavin1, A. G. Fairen7,8 and Paul R. Mahaffy1. 1NASA GSFC, Code 699, Greenbelt, MD 20771, [email protected], 2Jacobs, NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston, TX 77058, 3Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409, 4Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México, D.F. 04510, Mexico, 5NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 94035, 6NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston TX 77058, 7Centro de Astrobiologia, Madrid, Spain, 8Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 Introduction: Recent detection of nitrate on Mars [1] indicates that nitrogen fixation processes occurred in early martian history. Data collected by the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument on the Curiosity Rover can be integrated with Mars analog work in order to better understand the fixation and mobility of nitrogen on Mars, and thus its availability to putative biology. In particular, the relationship between nitrate and other soluble salts may help reveal the timing of nitrogen fixation and post-depositional behavior of nitrate on Mars. In addition, in situ measurements of nitrogen abundance and isotopic composition may be used to model atmospheric conditions on early Mars. Methods: The data presented are from analyses of solid Martian drilled and scooped samples by the Sam- ple Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument suite on the Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) Curiosity Rover. SAM performs evolved gas analysis (EGA), in which a 3 Figure 1. -

Andy Arleo Université De Nantes (CRINI)

LAURA NYRO’S ELI AND THE THIRTEENTH CONFESSION: TRANSCENDING THE DICHOTOMIES OF THE WOODSTOCK YEARS Andy Arleo Université de Nantes (CRINI) As Wavy Gravy says, if you can remember the sixties, you weren't really there (Van Ronk 141) Introduction1 As a member of the so-called Woodstock Generation, I am aware of the potential pitfalls of writing about this period. As Dave Van Ronk points out in his quote from Merry Prankster Wavy Gravy (Hugh Romney), memories of those times tend to be hazy. On the other hand, research on memory has shown that there is a “reminiscence bump,” that is “people tend to remember disproportionately more events from the period between their adolescence and early adulthood” (Foster 64). In any case, it is clear that memory, whether it is individual and collective, reconstructs past experience, and that my own experience of the era has inevitably flavored the content of this article, making it impossible to aspire completely to the traditional ideals of scholarly distance and detachment. Future generations of cultural analysts will no doubt reassess the Woodstock Years through different lenses. The name “Laura Nyro” may not ring a bell for many readers, as it did not for many of my students, colleagues and friends whom I have informally surveyed. This is understandable since, unlike other singer-songwriter icons of the period (e.g., Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, James Taylor), Nyro was never really in the mainstream, although her songs have often been covered by a broad spectrum of singers and bands in a remarkable variety of musical styles, sometimes achieving a fair amount of commercial success. -

Non-Collider Searches for Stable Massive Particles

Non-collider searches for stable massive particles S. Burdina, M. Fairbairnb, P. Mermodc,, D. Milsteadd, J. Pinfolde, T. Sloanf, W. Taylorg aDepartment of Physics, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7ZE, UK bDepartment of Physics, King's College London, London WC2R 2LS, UK cParticle Physics department, University of Geneva, 1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland dDepartment of Physics, Stockholm University, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden ePhysics Department, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada T6G 0V1 fDepartment of Physics, Lancaster University, Lancaster LA1 4YB, UK gDepartment of Physics and Astronomy, York University, Toronto, ON, Canada M3J 1P3 Abstract The theoretical motivation for exotic stable massive particles (SMPs) and the results of SMP searches at non-collider facilities are reviewed. SMPs are defined such that they would be suffi- ciently long-lived so as to still exist in the cosmos either as Big Bang relics or secondary collision products, and sufficiently massive such that they are typically beyond the reach of any conceiv- able accelerator-based experiment. The discovery of SMPs would address a number of important questions in modern physics, such as the origin and composition of dark matter and the unifi- cation of the fundamental forces. This review outlines the scenarios predicting SMPs and the techniques used at non-collider experiments to look for SMPs in cosmic rays and bound in mat- ter. The limits so far obtained on the fluxes and matter densities of SMPs which possess various detection-relevant properties such as electric and magnetic charge are given. Contents 1 Introduction 4 2 Theory and cosmology of various kinds of SMPs 4 2.1 New particle states (elementary or composite) . -

Scobie on I'm Not There

I’M NOT THERE (1956-2007) Stephen Scobie Je est un autre—Arthur Rimbaud I’m Not There (2007) In this autumn season of 2007, I can see that I am going to be thinking a lot about the Bob Dylan song known as “I’m Not There (1956).” At least, that is the title given to it on most of its early, bootleg appearances. Now that it has finally been officially released, the sub-title date has been dropped—which is a pity (since it added an element of mystery to the song) but also understandable (since no good explanation of the date has ever been given). “I’m Not There” is perhaps the ultimate Dylan bootleg, and has always been a subject for cult idealization as the most obscure of Dylan’s “lost” songs: a major master- piece that almost no one knows, and which indeed seems to conspire actively against being known. Now, it has become the title of Todd Haynes’s movie I’m Not There, “inspired by the music and many lives of Bob Dylan”—“many” being the operative word. The film is already famous for casting six different actors to play aspects of Dylan at different points in his career. If this strategy is a gimmick, it is a successful one: the film is generating vast amounts of advance publicity, much of it based on the photographs of Cate Blanchett looking, uncannily and androgynously, like 1966 Bob. The film is not due for North American release until late November, though it has played in prestigious festivals like Toronto, New York, and Venice. -

Perchlorate and Chlorate Biogeochemistry in Ice-Covered Lakes of the Mcmurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 98 (2012) 19–30 www.elsevier.com/locate/gca Perchlorate and chlorate biogeochemistry in ice-covered lakes of the McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica W. Andrew Jackson a,⇑, Alfonso F. Davila b,c, Nubia Estrada a, W. Berry Lyons d, John D. Coates e, John C. Priscu f a Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409, USA b NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA 95136, USA c SETI Institute, 189 Bernardo Ave., Suite 100, Mountain View, CA 94043-5203, USA d Byrd Polar Research Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA e Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA f Department of Land Resources & Environmental Sciences, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT 59717, USA Received 15 February 2012; accepted in revised form 5 September 2012; available online 19 September 2012 Abstract À À We measured chlorate (ClO3 ) and perchlorate (ClO4 ) concentrations in ice covered lakes of the McMurdo Dry Valleys À À (MDVs) of Antarctica, to evaluate their role in the ecology and geochemical evolution of the lakes. ClO3 and ClO4 are À À present throughout the MDV Lakes, streams, and other surface water bodies. ClO3 and ClO4 originate in the atmosphere and are transported to the lakes by surface inflow of glacier melt that has been differentially impacted by interaction with soils À À and aeolian matter. Concentrations of ClO3 and ClO4 in the lakes and between lakes vary based on both total evaporative concentration, as well as biological activity within each lake. -

Charles Wiles - Poems

Poetry Series Charles Wiles - poems - Publication Date: 2008 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Charles Wiles() www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 .....If Love Were Like Water (Best Love Poems) If love were like water I'd build you a fountain, And if love were like stone I'd bring you a mountain. If love were like air I'd set whirlwinds free, But as these are not love I'll just give you me. (1995) Charles Wiles www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 2 .....When I Wake Up Every Morning (Best Love Poems) When I wake up every morning I always watch you for a while Then I kiss you very lightly, Watch you lips turn to a smile. Then you ask me what the time is And I whisper in your ear That the hour hardly matters When you're lying warm and near. Your smile grows slightly wider, But you turn your face away, Hide your head under the pillow, Try to cheat the break of day. Your hair wisps round about you, Flows like water to your hips, But your neck soon bare before me Feels the pressure of my lips. Then I touch you very lightly, Run my fingers down your spine, And your body gently waking Turns till eyes gaze into mine. And in that very moment, As your mouth seeks to entice, When I wake up every morning, I am lost in paradise. (June 2007) Charles Wiles www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 3 .....You Ask How Much I Love You (Best Love Poems) You ask how much I love you And then you ask once more And so my love I'll tell you now As I did once before. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

In Pdf Format

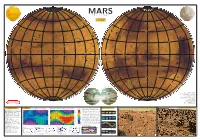

lós 1877 Mik 88 ge N 18 e N i h 80° 80° 80° ll T 80° re ly a o ndae ma p k Pl m os U has ia n anum Boreu bal e C h o A al m re u c K e o re S O a B Bo l y m p i a U n d Planum Es co e ria a l H y n d s p e U 60° e 60° 60° r b o r e a e 60° l l o C MARS · Korolev a i PHOTOMAP d n a c S Lomono a sov i T a t n M 1:320 000 000 i t V s a Per V s n a s l i l epe a s l i t i t a s B o r e a R u 1 cm = 320 km lkin t i t a s B o r e a a A a A l v s l i F e c b a P u o ss i North a s North s Fo d V s a a F s i e i c a a t ssa l vi o l eo Fo i p l ko R e e r e a o an u s a p t il b s em Stokes M ic s T M T P l Kunowski U 40° on a a 40° 40° a n T 40° e n i O Va a t i a LY VI 19 ll ic KI 76 es a As N M curi N G– ra ras- s Planum Acidalia Colles ier 2 + te . -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

A Review of Sample Analysis at Mars-Evolved Gas Analysis Laboratory Analog Work Supporting the Presence of Perchlorates and Chlorates in Gale Crater, Mars

minerals Review A Review of Sample Analysis at Mars-Evolved Gas Analysis Laboratory Analog Work Supporting the Presence of Perchlorates and Chlorates in Gale Crater, Mars Joanna Clark 1,* , Brad Sutter 2, P. Douglas Archer Jr. 2, Douglas Ming 3, Elizabeth Rampe 3, Amy McAdam 4, Rafael Navarro-González 5,† , Jennifer Eigenbrode 4 , Daniel Glavin 4 , Maria-Paz Zorzano 6,7 , Javier Martin-Torres 7,8, Richard Morris 3, Valerie Tu 2, S. J. Ralston 2 and Paul Mahaffy 4 1 GeoControls Systems Inc—Jacobs JETS Contract at NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston, TX 77058, USA 2 Jacobs JETS Contract at NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston, TX 77058, USA; [email protected] (B.S.); [email protected] (P.D.A.J.); [email protected] (V.T.); [email protected] (S.J.R.) 3 NASA Johnson Space Center, Houston, TX 77058, USA; [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (E.R.); [email protected] (R.M.) 4 NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA; [email protected] (A.M.); [email protected] (J.E.); [email protected] (D.G.); [email protected] (P.M.) 5 Institito de Ciencias Nucleares, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, Mexico City 04510, Mexico; [email protected] 6 Centro de Astrobiología (INTA-CSIC), Torrejon de Ardoz, 28850 Madrid, Spain; [email protected] 7 Department of Planetary Sciences, School of Geosciences, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen AB24 3FX, UK; [email protected] 8 Instituto Andaluz de Ciencias de la Tierra (CSIC-UGR), Armilla, 18100 Granada, Spain Citation: Clark, J.; Sutter, B.; Archer, * Correspondence: [email protected] P.D., Jr.; Ming, D.; Rampe, E.; † Deceased 28 January 2021.