Scobie on I'm Not There

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

County Theater ART HOUSE

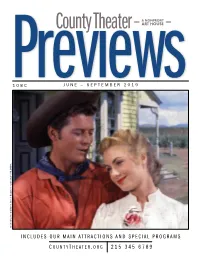

A NONPROFIT County Theater ART HOUSE Previews108C JUNE – SEPTEMBER 2019 Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones in Rodgers & Hammerstein’s OKLAHOMA! & Hammerstein’s in Rodgers Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS C OUNTYT HEATER.ORG 215 345 6789 Welcome to the nonprofit County Theater The County Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. Policies ADMISSION Children under 6 – Children under age 6 will not be admitted to our films or programs unless specifically indicated. General ............................................................$11.25 Late Arrivals – The Theater reserves the right to stop selling Members ...........................................................$6.75 tickets (and/or seating patrons) 10 minutes after a film has Seniors (62+) & Students ..................................$9.00 started. Matinees Outside Food and Drink – Patrons are not permitted to bring Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 outside food and drink into the theater. Sat & Sun before 2:30 .....................................$9.00 Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ........................$8.00 Accessibility & Hearing Assistance – The County Theater has wheelchair-accessible auditoriums and restrooms, and is Affiliated Theater Members* ...............................$6.75 equipped with hearing enhancement headsets and closed cap- You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. tion devices. (Please inquire at the concession stand.) The above ticket prices are subject to change. Parking Check our website for parking information. THANK YOU MEMBERS! Your membership is the foundation of the theater’s success. Without your membership support, we would not exist. Thank you for being a member. Contact us with your feedback How can you support or questions at 215 348 1878 x115 or email us at COUNTY THEATER the County Theater? MEMBER [email protected]. -

1974 Tour with the Band

BOB DYLAN / THE BAND (a collectors guide to the 74 Tour) BOB DYLAN / THE BAND - a collectors guide to the 74 Tour “There are two problems with the 1974 tour: the tapes are crap and Dylan‟s performances are crap.” – C. Heylin, Telegraph 32 pg 86. Introduction This booklet / File (like the anonymous companion volume “Songs of the Underground” for RTR) is intended to document the audio resources available to collectors concerning the 1974 tour with the Band. It is intended to supplement and possibly correct the three major resources available to collectors (Krogsgaard, Dundas & Olof‟s files). Several PA tapes have emerged since Krogsgaard was last updated, and (I believe) there are errors in Dundas (concerning the PA tapes from 11 Feb 1974) that I wished to address. Additionally, none of these references (except for one full listing in Krogsgaard) include the Band sets. While details are difficult to obtain, I have included details of about three- quarters of the Band sets. It is hoped that readers on the web may contribute more information. I believe that the Band was a significant contributor to the 1974 Tour and should be included in any 1974 Tour documentation. I have also identified the sources for the Vinyl and CD bootlegs, where my resources allowed. Often the attributions on Bootlegs are misleading, incomplete or wrong. As an example „Before and After the Flood‟ claims to be from MSG NYC 30.1.1974 when it is actually a combination of the PA tapes from 31.1.74 (evening) and 11.2.74 (evening). -

Making Changes Happe Making Changes Happen in Terra

CHAPTER ONE MAKING CHANGES HAPPEHAPPENN IN TERRA INCOGNITA A Process of Re-enactment I picked up my New York Times on April 20, 2012 and read that Levon Helm had died. I quietly turned to the obituary page and as I read what was written about this man, memories flooded back to me. The drinking age was twenty-one so we had to sneak in the back door off Yonge Street, Toronto’s main drag. It was a seedy section of the street below Bloor then, lined with strip joints and bars, and because of this it was one of places where you could go and hear exciting music in the early sixties. I was there with my friend, John. The two of us were freshly admitted undergraduate students at the University of Waterloo and anxious to make early marks in life. So we became concert promoters. This was a short career because even then concerts were presented by organized thugs and there was no room for amateurs like us. On one occasion we brought into town a singer who had a number one hit in Canada, Ronnie Hawkins and his band, known then as the Hawks. We got to know Ronnie pretty well and he was kind to us ingénues. About two weeks after the concert we got a phone call from Ronnie’s manager inviting us to come into the city and watch the band play for what he called an interview. So, on a Friday afternoon John and I crammed into our friend Ted’s Porsche 356 and headed down Highway 401. -

Wednesday Morning, May 22

WEDNESDAY MORNING, MAY 22 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View (cc) (TV14) Live! With Kelly and Michael Win- 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) ners Week. (N) (cc) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today America’s best beaches; Paul Anka. (N) (cc) The Jeff Probst Show (N) (cc) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) (TV14) EXHALE: Core Wild Kratts Bad Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! Pin- Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Baby Bear is embar- Daniel Tiger’s Sid the Science WordWorld (TVY) Barney & Friends 10/KOPB 10 10 Fusion (TVG) Hair Day. (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot occhio. (TVY) (TVY) rassed about his doll. (TVY) Neighborhood Kid (cc) (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) The 700 Club People find finan- Paid Paid Better (N) (cc) (TVPG) 12/KPTV 12 12 cial health. (N) (cc) (TVG) Paid Tomorrow’s World Paid Paid Through the Bible Paid Paid Paid Paid Paid Zula Patrol (cc) Pearlie (TVY7) 22/KPXG 5 5 (TVY) (TVY) Creflo Dollar (cc) John Hagee Joseph Prince This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Alive With Kong Against All Odds Pro-Claim Behind the Joyce Meyer Life Today With Today With Mari- 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) (TVG) Scenes (cc) James Robison lyn & Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) The Steve Wilkos Show (cc) (TV14) The Bill Cunningham Show Deep Jerry Springer Some of the most- The Steve Wilkos Show (cc) (TV14) 32/KRCW 3 3 Dark Family Secrets. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses `This is what Salvation must be like after a While': Bob Dylan's Critical Utopia KOUVAROU, MARIA How to cite: KOUVAROU, MARIA (2011) `This is what Salvation must be like after a While': Bob Dylan's Critical Utopia, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1391/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ‘This is what Salvation must be like after a While’: Bob Dylan’s Critical Utopia Maria Kouvarou MA by Research in Musicology Music Department Durham University 2011 Maria Kouvarou ‘This is what Salvation must be like after a While’: Bob Dylan’s Critical Utopia Abstract Bob Dylan’s work has frequently been the object of discussion, debate and scholarly research. It has been commented on in terms of interpretation of the lyrics of his songs, of their musical treatment, and of the distinctiveness of Dylan’s performance style, while Dylan himself has been treated both as an important figure in the world of popular music, and also as an artist, as a significant poet. -

Bob Denson Master Song List 2020

Bob Denson Master Song List Alphabetical by Artist/Band Name A Amos Lee - Arms of a Woman - Keep it Loose, Keep it Tight - Night Train - Sweet Pea Amy Winehouse - Valerie Al Green - Let's Stay Together - Take Me To The River Alicia Keys - If I Ain't Got You - Girl on Fire - No One Allman Brothers Band, The - Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More - Melissa - Ramblin’ Man - Statesboro Blues Arlen & Harburg (Isai K….and Eva Cassidy and…) - Somewhere Over the Rainbow Avett Brothers - The Ballad of Love and Hate - Head Full of DoubtRoad Full of Promise - I and Love and You B Bachman Turner Overdrive - Taking Care Of Business Band, The - Acadian Driftwood - It Makes No Difference - King Harvest (Has Surely Come) - Night They Drove Old Dixie Down, The - Ophelia - Up On Cripple Creek - Weight, The Barenaked Ladies - Alcohol - If I Had A Million Dollars - I’ll Be That Girl - In The Car - Life in a Nutshell - Never is Enough - Old Apartment, The - Pinch Me Beatles, The - A Hard Day’s Night - Across The Universe - All My Loving - Birthday - Blackbird - Can’t Buy Me Love - Dear Prudence - Eight Days A Week - Eleanor Rigby - For No One - Get Back - Girl Got To Get You Into My Life - Help! - Her Majesty - Here, There, and Everywhere - I Saw Her Standing There - I Will - If I Fell - In My Life - Julia - Let it Be - Love Me Do - Mean Mr. Mustard - Norwegian Wood - Ob-La-Di Ob-La-Da - Polythene Pam - Rocky Raccoon - She Came In Through The Bathroom Window - She Loves You - Something - Things We Said Today - Twist and Shout - With A Little Help From My Friends - You’ve -

Andy Arleo Université De Nantes (CRINI)

LAURA NYRO’S ELI AND THE THIRTEENTH CONFESSION: TRANSCENDING THE DICHOTOMIES OF THE WOODSTOCK YEARS Andy Arleo Université de Nantes (CRINI) As Wavy Gravy says, if you can remember the sixties, you weren't really there (Van Ronk 141) Introduction1 As a member of the so-called Woodstock Generation, I am aware of the potential pitfalls of writing about this period. As Dave Van Ronk points out in his quote from Merry Prankster Wavy Gravy (Hugh Romney), memories of those times tend to be hazy. On the other hand, research on memory has shown that there is a “reminiscence bump,” that is “people tend to remember disproportionately more events from the period between their adolescence and early adulthood” (Foster 64). In any case, it is clear that memory, whether it is individual and collective, reconstructs past experience, and that my own experience of the era has inevitably flavored the content of this article, making it impossible to aspire completely to the traditional ideals of scholarly distance and detachment. Future generations of cultural analysts will no doubt reassess the Woodstock Years through different lenses. The name “Laura Nyro” may not ring a bell for many readers, as it did not for many of my students, colleagues and friends whom I have informally surveyed. This is understandable since, unlike other singer-songwriter icons of the period (e.g., Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, James Taylor), Nyro was never really in the mainstream, although her songs have often been covered by a broad spectrum of singers and bands in a remarkable variety of musical styles, sometimes achieving a fair amount of commercial success. -

The Eight of Swords Sandra L

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 The Eight of Swords Sandra L. Giles Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE EIGHT OF SWORDS By SANDRA L. GILES A Dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the dissertation of Sandra L. Giles on 6 February 2008. _________________________ Virgil Suarez Professor Directing Dissertation _________________________ Susan Nelson Wood Outside Committee Member _________________________ R. M. Berry Committee Member _________________________ Deborah Coxwell-Teague Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Deep and sincere thanks go to my committee members: Virgil Suarez, R.M. Berry, Deborah Coxwell-Teague, Susan Nelson Wood. Thanks also go to the members of Mark Winegardner’s Fiction Writing Workshop in Fall of 2002, in which this novel began as a short story and received thoughtful critique. I received valuable advice and information from Mavis LaBounty, Sissy Taylor-Maloy, and other members of the “Goddess Group” in Tallahassee, Florida, as well as from Officer Tom King of the Tifton Police Department, the Tiftarea Writers Haven writing group, and my sister, Debra -

Colin Linden – Blow Biography

Colin Linden – bLOW Biography “Got a coin in my pocket heavy and gold/It don’t own me I need to let it go/Cause having is wanting/Desire can make you weep” – “bLOW” Colin Linden’s tale is the stuff of legend, the kind told in the Coen brothers’ O Brother Where Art Thou or Inside Llewyn Davis, both of which featured his guitar playing on the soundtracks. That film would begin with an 11-year-old meeting his musical idol Howlin’ Wolf at a matinee show in his native Toronto, accompanied by his mom, who took a picture of the two during a nearly two-hour long conversation before the gig, the legendary bluesman idling over coffee and cigarettes. “I’m an old man now, and I won’t be around much longer,” Wolf told him. “It’s up to you to carry it on.” Linden still carries that frayed photograph in his wallet, along with a Sears 5/8” socket wrench in his pocket to play slide guitar. He has taken Wolf’s plea seriously, performing since he was 12 years old, leaving home as a teenager to travel the south at the invitation of Mississippi Sheiks delta blues guitarist Sam Chatmon which took him to Detroit, Chicago, Indianapolis, St. Louis, Memphis and Hollandale, Mississippi, meeting and visiting the sites of his heroes – Brownie McGhee, Muddy Waters, Sippie Wallace, Tampa Red, Blind John Davis, the Rev. Robert Wilkins, Sleepy John Estes and Son House, visiting the landmarks and juke joints, many of which he’s played in during the course of a 45-year career producing and playing blues and roots music. -

NO ONE KNOWS ABOUT US by Bridget Canning. a Creative Writing

NO ONE KNOWS ABOUT US By Bridget Canning. A Creative Writing Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in English (Creative Writing) Department of English, Memorial University of Newfoundland Abstract: No One Knows about Us is a collection of twelve contemporary short stories. As the title suggests, the characters in each story deal with secrets: relationships, longings, grudges, addictions, and trickery. For them, these secrets are simultaneously overwhelming and futile; their importance within their small worlds reflect a deeper feeling of insignificance in the greater scheme of life in a small city in a northern province hemmed on to the side of a continent. Here are a range of characters and situations set in St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador. The stories are mapped out in different areas of the city and move chronologically over a year, starting in fall and ending in late summer. They work together to create a small sample of life in modern-day St. John’s – one that is informed by the influences of history, economy, and weather. i Acknowledgements: This thesis would not have been accomplished without the help of the English department faculty at Memorial such as Robert Finley, Robert Chafe, and especially my thesis advisor, Lisa Moore. Thanks to the Graduate Society for their financial support. Thanks to Jonathan Weir, Deirdre Snook, and the members of the Naked Parade Writing Collective for their guidance and encouragement. ii Contents: 1. Seen, p. 1 2. With Glowing Hearts, p. 19 3. -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

A MADONNA with GYPSY BLOOD the Love Ideal in Bob Dylan's Songs

A MADONNA WITH GYPSY BLOOD The love ideal in Bob Dylan ’s songs Jan-Hendrik Bakker It was during one of the Poetry International Festivals in the early nineties. Students from the academy for cinematographic art were preparing a documentary about people and their poetic favorites. Their approach was to surprise festival attendees by asking them to recite a poem they knew by heart. Later their recitations would be recorded on video. I still remember it really turned out to be a nice documentary. I happened to become one of their victims. Walt Whitman is my favorite poet, but, unfortunately in this case, I do not know by heart the huge amounts of text that this nineteenth century, bearded bard had produced. So I hesitated for awhile, but after a short time these words came up: Nobody feels any pain,/ tonight as I stand inside the rain/ Everybody knows,/ that baby ’s got new clothes/ but lately I ’ve seen her ribbons and her bows/ have fallen from her curls... One of the young men looked at me as if I had just made a joke. No sorry, this was not what he meant. I said I was sorry too, couldn ’t help it. This kind of poetry is part of my inner system, more than Nijhoff and Hendrik de Vries 1, who, I have to confess, are beautiful poets as well. It must be due to my generation; while others were exposed to the poetry of Jacques Pr évert or Jacques Brel in their childhood days, it was the songs of Bob Dylan, especially his love songs that left their imprints in my blood.