TEE VOYAGE of HMS CHALLENGER. ZOOLOGY. REPORT on The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anthopleura and the Phylogeny of Actinioidea (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Actiniaria)

Org Divers Evol (2017) 17:545–564 DOI 10.1007/s13127-017-0326-6 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Anthopleura and the phylogeny of Actinioidea (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Actiniaria) M. Daly1 & L. M. Crowley2 & P. Larson1 & E. Rodríguez2 & E. Heestand Saucier1,3 & D. G. Fautin4 Received: 29 November 2016 /Accepted: 2 March 2017 /Published online: 27 April 2017 # Gesellschaft für Biologische Systematik 2017 Abstract Members of the sea anemone genus Anthopleura by the discovery that acrorhagi and verrucae are are familiar constituents of rocky intertidal communities. pleisiomorphic for the subset of Actinioidea studied. Despite its familiarity and the number of studies that use its members to understand ecological or biological phe- Keywords Anthopleura . Actinioidea . Cnidaria . Verrucae . nomena, the diversity and phylogeny of this group are poor- Acrorhagi . Pseudoacrorhagi . Atomized coding ly understood. Many of the taxonomic and phylogenetic problems stem from problems with the documentation and interpretation of acrorhagi and verrucae, the two features Anthopleura Duchassaing de Fonbressin and Michelotti, 1860 that are used to recognize members of Anthopleura.These (Cnidaria: Anthozoa: Actiniaria: Actiniidae) is one of the most anatomical features have a broad distribution within the familiar and well-known genera of sea anemones. Its members superfamily Actinioidea, and their occurrence and exclu- are found in both temperate and tropical rocky intertidal hab- sivity are not clear. We use DNA sequences from the nu- itats and are abundant and species-rich when present (e.g., cleus and mitochondrion and cladistic analysis of verrucae Stephenson 1935; Stephenson and Stephenson 1972; and acrorhagi to test the monophyly of Anthopleura and to England 1992; Pearse and Francis 2000). -

Carl Gegenbaur – Wikipedia

Carl Gegenbaur – Wikipedia http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Gegenbaur aus Wikipedia, der freien Enzyklopädie Carl Gegenbaur (* 21. August 1826 in Würzburg; † 14. Juni 1903 in Heidelberg) war ein deutscher Arzt, einer der bedeutendsten Wirbeltiermorphologen des 19. Jahrhunderts und einer der Väter der Evolutionsmorphologie, eines modernen Begriffs von Walter J. Bock und Dwight D. Davis. 1 Leben 2 Wissenschaftliche Leistung 2.1 Das „Kopf-Problem“ 3 Verhältnis Carl Gegenbaur und Ernst Haeckel 4 Nach Gegenbaur benannte Taxa Carl Gegenbaur 5 Ausgewählte Arbeiten 6 Weiterführende Literatur 7 Weblinks 8 Einzelnachweise Er war der Sohn des Justizbeamten Franz Joseph Gegenbaur (1792–1872) und dessen Ehefrau Elisabeth Karoline (1800–1866), geb. Roth. Von seinen sieben Geschwistern verstarben vier sehr jung; sein um drei Jahre jüngerer Bruder wurde nur 25 Jahre und seine um 13 Jahre jüngere Schwester 38 Jahre alt.[1] 1838 besuchte er die Lateinschule und von 1838 bis 1845 in Würzburg das Gymnasium. Schon zu seiner Schulzeit führt er Naturstudien in der Umgebung von Würzburg und bei Verwandten im Odenwald (Amorbach) durch. Er beschäftigt sich weiterführend mit Pflanzen, Tieren, Gesteinen, legte Sammlungen an, fertigte Zeichnungen und führte erste Tiersektionen durch.[2] Politische Hintergründe: Bayern wurde 1806 unter dem Minister Maximilian Carl Joseph Franz de Paula Hieronymus Graf von Montgelas (1759–1838) zu einem der führenden Mitglieder im Rheinbund und Bündnispartner von Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821). Für seine Bündnistreue wurde im Frieden von Pressburg Bayern zum Königreich durch den französischen Kaiser aufgewertet und Herzog Maximilian IV. (1756–1825) am 1. Januar 1806 in München als Maximilian I. Joseph zum ersten König Bayerns erhoben. -

CNIDARIA Corals, Medusae, Hydroids, Myxozoans

FOUR Phylum CNIDARIA corals, medusae, hydroids, myxozoans STEPHEN D. CAIRNS, LISA-ANN GERSHWIN, FRED J. BROOK, PHILIP PUGH, ELLIOT W. Dawson, OscaR OcaÑA V., WILLEM VERvooRT, GARY WILLIAMS, JEANETTE E. Watson, DENNIS M. OPREsko, PETER SCHUCHERT, P. MICHAEL HINE, DENNIS P. GORDON, HAMISH J. CAMPBELL, ANTHONY J. WRIGHT, JUAN A. SÁNCHEZ, DAPHNE G. FAUTIN his ancient phylum of mostly marine organisms is best known for its contribution to geomorphological features, forming thousands of square Tkilometres of coral reefs in warm tropical waters. Their fossil remains contribute to some limestones. Cnidarians are also significant components of the plankton, where large medusae – popularly called jellyfish – and colonial forms like Portuguese man-of-war and stringy siphonophores prey on other organisms including small fish. Some of these species are justly feared by humans for their stings, which in some cases can be fatal. Certainly, most New Zealanders will have encountered cnidarians when rambling along beaches and fossicking in rock pools where sea anemones and diminutive bushy hydroids abound. In New Zealand’s fiords and in deeper water on seamounts, black corals and branching gorgonians can form veritable trees five metres high or more. In contrast, inland inhabitants of continental landmasses who have never, or rarely, seen an ocean or visited a seashore can hardly be impressed with the Cnidaria as a phylum – freshwater cnidarians are relatively few, restricted to tiny hydras, the branching hydroid Cordylophora, and rare medusae. Worldwide, there are about 10,000 described species, with perhaps half as many again undescribed. All cnidarians have nettle cells known as nematocysts (or cnidae – from the Greek, knide, a nettle), extraordinarily complex structures that are effectively invaginated coiled tubes within a cell. -

The Dancing Bees: Karl Von Frisch, the Honeybee Dance Language

The Dancing Bees: Karl von Frisch, the Honeybee Dance Language, and the Sciences of Communication By Tania Munz, Research Fellow MPIWG, [email protected] In January of 1946, while much of Europe lay buried under the rubble of World War Two, the bee researcher Karl von Frisch penned a breathless letter from his country home in lower Austria. He reported to a fellow animal behaviorist his “sensational findings about the language of the bees.”1 Over the previous summer, he had discovered that the bees communicate to their hive mates the distance and direction of food sources by means of the “dances” they run upon returning from foraging flights. The straight part of the figure-eight-shaped waggle dance makes the same angle with the vertical axis of the hive as the bee’s flight line from the hive made with the sun during her outgoing flight. Moreover, he found that the frequency of individual turns correlated closely with the distance of the food; the closer the supply, the more rapidly the bee dances. Von Frisch’s assessment in the letter to his colleague would prove correct – news of the discovery was received as a sensation and quickly spread throughout Europe and abroad. In 1973, von Frisch was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine together with the fellow animal behaviorists Konrad Lorenz and Niko Tinbergen. The Prize bestowed public recognition that non-human animals possess a symbolic means of communication. Dancing Bees is a dual intellectual biography – about the life and work of the experimental physiologist Karl von Frisch on the one hand and the honeybees as cultural, experimental, and especially communicating animals on the other. -

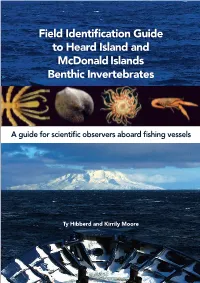

Benthic Field Guide 5.5.Indb

Field Identifi cation Guide to Heard Island and McDonald Islands Benthic Invertebrates Invertebrates Benthic Moore Islands Kirrily and McDonald and Hibberd Ty Island Heard to Guide cation Identifi Field Field Identifi cation Guide to Heard Island and McDonald Islands Benthic Invertebrates A guide for scientifi c observers aboard fi shing vessels Little is known about the deep sea benthic invertebrate diversity in the territory of Heard Island and McDonald Islands (HIMI). In an initiative to help further our understanding, invertebrate surveys over the past seven years have now revealed more than 500 species, many of which are endemic. This is an essential reference guide to these species. Illustrated with hundreds of representative photographs, it includes brief narratives on the biology and ecology of the major taxonomic groups and characteristic features of common species. It is primarily aimed at scientifi c observers, and is intended to be used as both a training tool prior to deployment at-sea, and for use in making accurate identifi cations of invertebrate by catch when operating in the HIMI region. Many of the featured organisms are also found throughout the Indian sector of the Southern Ocean, the guide therefore having national appeal. Ty Hibberd and Kirrily Moore Australian Antarctic Division Fisheries Research and Development Corporation covers2.indd 113 11/8/09 2:55:44 PM Author: Hibberd, Ty. Title: Field identification guide to Heard Island and McDonald Islands benthic invertebrates : a guide for scientific observers aboard fishing vessels / Ty Hibberd, Kirrily Moore. Edition: 1st ed. ISBN: 9781876934156 (pbk.) Notes: Bibliography. Subjects: Benthic animals—Heard Island (Heard and McDonald Islands)--Identification. -

Preface for Uchida Anniversary Volume

Title PREFACE FOR UCHIDA ANNIVERSARY VOLUME Author(s) WITSCHI, Emil Citation 北海道大學理學部紀要, 13(1-4) Issue Date 1957-08 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/27187 Type bulletin (editorial) File Information 13(1_4)_Preface.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP 'V PREFACE FOR UCHIDA ANNIVERSARY VOLUME My personal acquaintance with Tohru Uchida dates back to the summer of 1931. Accompanied by his charming wife, he paid us a visit at Iowa City, on the return trip to Japan from Berlin and Miinchen. Two years of study with Richard Goldschmidt and Karl von Frisch had made him a member of the scien tific family of Richard Hertwig .... not only by contact. Well prepared through 'years of training at the great school of Zoologists in T~kyo, he had nevertheless preserved a youthful adaptability, that enabled him to gain full advantage from his study period abroad. Iowa was suffering under a spell of sweltering heat; but even while he was wiping the sweat from his brows, our visitor denied that the weather was unbearable. Indefatigably he was carrying on the conversations .... on the lawn in the shade of the trees and in the steaming laboratories. Then and there I realized that Doctor Uchida was not only a well informed student in the widely ramified field of sex research but an investigator of originality, filled with a great enthusiasm for scientific progress. After the return to his country Professor Uchida developed his own school at the progressive Hokkaido University. It soon became known also outside of Japan, because of the wide scope and variety of subject interests as well as the quality of its scientific production. -

Hidden Among Sea Anemones: the First Comprehensive Phylogenetic Reconstruction of the Order Actiniaria

Hidden among Sea Anemones: The First Comprehensive Phylogenetic Reconstruction of the Order Actiniaria (Cnidaria, Anthozoa, Hexacorallia) Reveals a Novel Group of Hexacorals Estefanı´a Rodrı´guez1*, Marcos S. Barbeitos2,3, Mercer R. Brugler1,2,4, Louise M. Crowley1, Alejandro Grajales1,4, Luciana Gusma˜o5, Verena Ha¨ussermann6, Abigail Reft7, Marymegan Daly8 1 Division of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, New York City, New York, United States of America, 2 Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics, American Museum of Natural History, New York City, New York, United States of America, 3 Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade Federal do Parana´, Curitiba, Brazil, 4 Richard Gilder Graduate School, American Museum of Natural History, New York City, New York, United States of America, 5 Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade de Sa˜o Paulo, Sa˜o Paulo, Brazil, 6 Escuela de Ciencias del Mar, Pontificia Universidad Cato´lica de Valparaı´so, Valparaı´so, Chile, 7 Department of Molecular Evolution and Genomics, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany, 8 Department of Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology, Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, United States of America Abstract Sea anemones (order Actiniaria) are among the most diverse and successful members of the anthozoan subclass Hexacorallia, occupying benthic marine habitats across all depths and latitudes. Actiniaria comprises approximately 1,200 species of solitary and skeleton-less polyps and lacks any anatomical synapomorphy. Although monophyly is anticipated based on higher-level molecular phylogenies of Cnidaria, to date, monophyly has not been explicitly tested and at least some hypotheses on the diversification of Hexacorallia have suggested that actiniarians are para- or poly-phyletic. -

Turtles As Hopeful Monsters: Origins and Evolution Book Reviewed By

Palaeontologia Electronica http://palaeo-electronica.org Turtles as Hopeful Monsters: Origins and Evolution Book reviewed by Darren Naish Turtles as Hopeful Monsters: Origins and Evolution, by Olivier Rieppel. 2017 Indiana University Press, Bloomington and Indianapolis. $45.00 ISBN 978-0-253-02475-6 It is cliché today to describe turtles as among the greatest of enigmas in the world of tetrapod evolutionary history. Turtles – Testudinata or Testu- dines, according to your preference (don’t use Chelonia, please) – are anatomically ridiculous (limbs and limb girdles inside the ribcage?), their unique Bauplan obscuring efforts to determine their affinities within Reptilia. Olivier Rieppel’s Turtles as Hopeful Monsters: Origins and Evolution dis- cusses, over six chapters, what we know of the tur- tle fossil record and what we think and have thought about turtle origins and evolution, though note that this work only discusses the earliest stages of turtle evolution and is not concerned with the clade’s in-group relations. More specifically, this most attractive book is devoted first and fore- most to Rieppel’s coverage of competing models of turtle origins and evolutionary history and the sci- entists involved, though it’s rather more compli- cated than that. Rieppel is one of the world’s foremost authori- ties on reptile anatomy and evolution and it turns out that he is not just a formidably qualified, highly experienced and respected scientist and science historian but an excellent and engaging popular writer as well. The volume is as much about the history and philosophy of evolutionary biology and those who have studied it as it is about the science itself. -

G Neuweiler: an Appreciation

Commentary G Neuweiler: An appreciation G Neuweiler, incumbent of one of the most prestigious chairs in zoology in Europe since 1980, retired from office on 1st October 2003. His successor in the Zoologisches Institut der Ludwig-Maximilians- University is a former student, Benedikt Grothe. Neuweiler was the fifth incumbent of this chair established in 1828, succeeding such illustrious zoologists as von Seebold, Richard Hertwig, Karl von Frisch and Hansjochem Autrum. Neuweiler has earned his respite, but not repose, after a forty-year academic career involving teaching, research and steering of the course of science policy after the 1970s in Germany and in post-merger Germany. Along with S Krishnaswamy, Neuweiler was the co- architect of the Indo-German Project on Animal Behaviour, a bi-national venture under the ‘Cultural Exchange Programme’ of the UGC and DAAD, between 1978 and 1988. The IGPAB was a colla- borative programme in research and teaching between the Zoology Department (first of Frankfurt University and after 1980) of the University of Munich and the School of Biological Sciences, Madurai Kamaraj University (MKU). The project led to significant findings on the biology, behaviour and the neurophysiology of echolocation of nine species of insectivorous bats of the Madurai. Further, Neuweiler was responsible in great measure for the extremely successful ‘All India Intensive Training Courses in Neurophysiology’ offered at the SBS/MKU in 1978, 1979 and 1981. G Neuweiler addressing a session of the Indian Academy of Sciences, held in the School of Biological Sciences, Madurai University in November 1985. Gerhard Neuweiler was born on 18th May 1935 in Nagold in the Black Forest as the fourth son of the school teacher Friedrich Neuweiler and his wife Luise. -

Ernst Haeckel and the Struggles Over Evolution and Religion

89 Ernst Haeckel and the Struggles over Evolution and Religion Robert J. Richards1 Abstract As a young man, Ernst Haeckel harbored a conventional set of Evangelical beliefs, mostly structured by the theology of Schleiermacher. But the conversion to Darwinian theory and the sudden death of his young wife shifted his ideas to the heterodox mode, more in line with Goethe and Spinoza. Haeckel’s battles with the religiously minded became more intense after 1880, with attack and counterattack. He particularly engaged Erich Wasmann, a Jesuit entomologist who had become an evolutionist, and the Keplerbund, an organization of Protestant thinkers who opposed evolutionary theory and accused him of deliberate fraud. In these struggles, Haeckel defined and deepened the opposition between traditional religion and evolutionary theory, and the fight continues today. If religion means a commitment to a set of theological propositions regarding the nature of God, the soul, and an afterlife, Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919) was never a religious en- thusiast. The influence of the great religious thinker Friedrich Daniel Schleiermacher (1768-1834) on his family kept religious observance decorous and commitment vague.2 The theologian had maintained that true religion lay deep in the heart, where the inner person experienced a feeling of absolute dependence. Dogmatic tenets, he argued, served merely as inadequate symbols of this fundamental experience. Religious feeling, accord- ing to Schleiermacher’s Über die Religion (On religion, 1799), might best be cultivated by seeking after truth, experiencing beauty, and contemplating nature.3 Haeckel practiced this kind of Schleiermachian religion all of his life. Haeckel’s association with the Evangelical Church, even as a youth, had been con- ventional. -

Sur Ridge Field Guide: Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary

Office of National Marine Sanctuaries National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Marine Conservation Science Series Sur Ridge Field Guide: Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary ©MBARI October 2017 | sanctuaries.noaa.gov | MARINE SANCTUARIES CONSERVATION SERIES ONMS-17-10 U.S. Department of Commerce Wilbur Ross, Secretary National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Benjamin Friedman, Acting Administrator National Ocean Service Russell Callender, Ph.D., Assistant Administrator Office of National Marine Sanctuaries John Armor, Director Report Authors: Erica J. Burton1, Linda A. Kuhnz2, Andrew P. DeVogelaere1, and James P. Barry2 1Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary National Ocean Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 99 Pacific Street, Bldg 455A, Monterey, CA, 93940, USA 2Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute 7700 Sandholdt Road, Moss Landing, CA, 95039, USA Suggested Citation: Burton, E.J., L.A. Kuhnz, A.P. DeVogelaere, and J.P. Barry. 2017. Sur Ridge Field Guide: Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Marine Sanctuaries Conservation Series ONMS- 17-10. U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, Silver Spring, MD. 122 pp. Cover Photo: Clockwise from top left: bamboo coral (Isidella tentaculum, foreground center), sea star (Hippasteria californica), Shortspine Thornyhead (Sebastolobus alascanus), and crab (Gastroptychus perarmatus). Credit: Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. About the Marine Sanctuaries Conservation Series The Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, serves as the trustee for a system of underwater parks encompassing more than 620,000 square miles of ocean and Great Lakes waters. The 13 national marine sanctuaries and two marine national monuments within the National Marine Sanctuary System represent areas of America’s ocean and Great Lakes environment that are of special national significance. -

Cnidaria (Coelenterata) Steven Sadro

Cnidaria (Coelenterata) Steven Sadro The cnidarians (coelenterates), encompassing hydroids, sea anemones, corals, and jellyfish, are a large (ca 5,500 species), highly diverse group. They are ubiquitous, occurring at all latitudes and depths. The phylum is divided into four classes, all found in the waters of the Pacific Northwest. This chapter is restricted to the two classes with a dominant polyp form, the Hydrozoa (Table 1) and Anthozoa (Table 2), and excludes the Scyphozoa, Siphonophora, and Cubozoa, which have a dominant medusoid form. Keys to the local Scyphozoa and Siphonophora can be found in Kozloff (1996), and Wrobel and Mills (1998) present a beautiful pictorial guide to these groups. Reproduction and Development The relatively simple cnidarian structural organization contrasts with the complexity of their life cycles (Fig. 1). The ability to form colonies or clones through asexual reproduction and the life cycle mode known as "alteration of generations" are the two fundamental aspects of the cnidarian life cycle that contribute to the group's great diversity (Campbell, 1974; Brusca and Brusca, 1990). The life cycle of many cnidarians alternates between sexual and asexual reproducing forms. Although not all cnidarians display this type of life cycle, those that do not are thought to have derived from taxa that did. The free-swimming medusoid is the sexually reproducing stage. It is generated through asexual budding of the polyp form. Most polyp and some medusae forms are capable of reproducing themselves by budding, and when budding is not followed by complete separation of the new cloned individuals colonies are formed (e.g., Anthopleura elegantissima).