UC San Diego UC San Diego Previously Published Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Textiles of the Han Dynasty & Their Relationship with Society

The Textiles of the Han Dynasty & Their Relationship with Society Heather Langford Theses submitted for the degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Centre of Asian Studies University of Adelaide May 2009 ii Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the research requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Centre of Asian Studies School of Humanities and Social Sciences Adelaide University 2009 iii Table of Contents 1. Introduction.........................................................................................1 1.1. Literature Review..............................................................................13 1.2. Chapter summary ..............................................................................17 1.3. Conclusion ........................................................................................19 2. Background .......................................................................................20 2.1. Pre Han History.................................................................................20 2.2. Qin Dynasty ......................................................................................24 2.3. The Han Dynasty...............................................................................25 2.3.1. Trade with the West............................................................................. 30 2.4. Conclusion ........................................................................................32 3. Textiles and Technology....................................................................33 -

The Sweep of History

STUDENT’S World History & Geography 1 1 1 Essentials of World History to 1500 Ver. 3.1.10 – Rev. 2/1/2011 WHG1 The following pages describe significant people, places, events, and concepts in the story of humankind. This information forms the core of our study; it will be fleshed-out by classroom discussions, audio-visual mat erials, readings, writings, and other act ivit ies. This knowledge will help you understand how the world works and how humans behave. It will help you understand many of the books, news reports, films, articles, and events you will encounter throughout the rest of your life. The Student’s Friend World History & Geography 1 Essentials of world history to 1500 History What is history? History is the story of human experience. Why study history? History shows us how the world works and how humans behave. History helps us make judgments about current and future events. History affects our lives every day. History is a fascinating story of human treachery and achievement. Geography What is geography? Geography is the study of interaction between humans and the environment. Why study geography? Geography is a major factor affecting human development. Humans are a major factor affecting our natural environment. Geography affects our lives every day. Geography helps us better understand the peoples of the world. CONTENTS: Overview of history Page 1 Some basic concepts Page 2 Unit 1 - Origins of the Earth and Humans Page 3 Unit 2 - Civilization Arises in Mesopotamia & Egypt Page 5 Unit 3 - Civilization Spreads East to India & China Page 9 Unit 4 - Civilization Spreads West to Greece & Rome Page 13 Unit 5 - Early Middle Ages: 500 to 1000 AD Page 17 Unit 6 - Late Middle Ages: 1000 to 1500 AD Page 21 Copyright © 1998-2011 Michael G. -

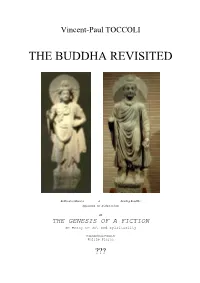

The Buddha Revisited

Vincent-Paul TOCCOLI THE BUDDHA REVISITED Bodhisattva Maitreya & Standing Bouddha Afghanistan, 1er & 2ème sicècles or THE GENESIS OF A FICTION an essay on art and spirituality Translated from French by Philip Pierce ??? "Stories do not belong to eternity "They belong to time "And out of time they grow... "It is in time "That stories, relived and redreamed "Become timeless... "Nations and people are largely the stories they feed themselves "If they tell themselves stories that are lies, "They will suffer the future consequences of those lies. "If they tell themselves stories that free their own truths "They will free their histories forfuture flowerings. (Ben OKRI, Birds of heaven, 25, 15) "Dans leur prétention à la sagesse, "Ils sont devenus fous, "Et ils ont changé la gloire du dieu incorruptible "Contre une représentation, "Simple image d`homme corruptible. (St Paul, to the Romans, 1, 22-23) C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION FIRST PART: THE MAKING-SENSE TRANSGRESSIONS 1st SECTION: ON THE GANGES SIDE, 5th-1st cent. BC. Chap.1: The Buddhism of the Buddha Chap.2: The state of Buddhism under the last Mauryas 2nd SECTION: ON THE INDUS SIDE, 4th-1st cent. BC. Chap.3: The permanence of Philhellenism, from the Graeco-bactrians to the Scytho-Parthans Chap.4: An approach to the graeco-hellenistic influence SECOND PART: THE ARTIFICIAL FECUNDATIONS 3rd SECTION: THE SYMBOLIC IMAGINARY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF THE SACRED Chap.5: The figurative vision of Buddhism Chap.6: The aesthetic tradition of Greek sculpture 4th SECTION: THE PRECIPITATE IN SPACE -

Engineering an Empire: Carthage

Hi. I’m Peter Weller for the Name: _____________________ History Channel. Join me while we explore Engineering An Empire: Carthage. Carthage *Carthage is in modern day Tunisia near the capital city of Tunis in North Africa. *Carthage dominated the Mediterranean world for over 600 years. *Roots in Phoenicians…4th century BC Empire dominating the Mediterranean. *By 650 BC nobody messes with Carthage who were wealthy. (Population 300,000) *For two centuries Carthage dominated the Mediterranean. But a rival across the sea to the north was developing into a military power…Rome. Start @ 15:30 into film. 1. Why are Rome and Carthage in conflict over Sicily? *Rome saw Carthage as a spear pointed right at the heart of Rome that had to be taken out. *Punic Wars named after the Latin word Punici = Rome’s word for the Phoenicians. 2. How do the Romans acquire Sicily? 3. Who was Hamilcar Barca? 4. How was a Quinquereme different from a Trireme? 5. How did the Romans improve their navy? 6. In the battle over the Aegates, why were the outnumbered Romans able to defeat the Carthaginians? 7. How did this effect Hamilcar’s forces in Sicily? 8. What did Rome gain in the victory? *Rome required Carthage pay a huge tribute in attempt to cripple it. 9. Carthage turned to _______________ to amass wealth. 10. What happened to Hamilcar in the battle for Rome? 11. Who was Hannibal Barca? 12. Describe the force that Hannibal marched to Rome with in 218 BC: 13. How did the Gauls respond to Hannibal’s army after they crossed the Rhone? 14. -

What the Romans Knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 • Part II

What the Romans knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 http://www.scaruffi.com/know • Part II 1 What the Romans knew Archaic Roma Capitolium Forum 2 (Museo della Civiltà Romana, Roma) What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Wars against Carthage resulted in conquest of the Phoenician and Greek civilizations – Greek pantheon (Zeus=Jupiter, Juno = Hera, Minerva = Athena, Mars= Ares, Mercury = Hermes, Hercules = Heracles, Venus = Aphrodite,…) – Greek city plan (agora/forum, temples, theater, stadium/circus) – Beginning of Roman literature: the translation and adaptation of Greek epic and dramatic poetry (240 BC) – Beginning of Roman philosophy: adoption of Greek schools of philosophy (155 BC) – Roman sculpture: Greek sculpture 3 What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Greeks: knowing over doing – Romans: doing over knowing (never translated Aristotle in Latin) – “The day will come when posterity will be amazed that we remained ignorant of things that will to them seem so plain” (Seneca, 1st c AD) – Impoverished mythology – Indifference to metaphysics – Pragmatic/social religion (expressing devotion to the state) 4 What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Western civilization = the combined effect of Greece's construction of a new culture and Rome's destruction of all other cultures. 5 What the Romans Knew • The Mediterranean Sea (Mare Nostrum) – Rome was mainly a sea power, an Etruscan legacy – Battle of Actium (31 BC) created the “mare nostrum”, a peaceful, safe sea for trade and communication – Disappearance of piracy – Sea routes were used by merchants, soldiers, -

Social Memory in the Eclogues of Virgil and Calpurnius Siculus

“Now I have forgotten all my verses”: Social Memory in the Eclogues of Virgil and Calpurnius Siculus Paul Hulsenboom Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen Abstract This paper examines the use of social memory in the pastoral poetry of Virgil and Cal- purnius Siculus. A comparison of the references to Rome’s social memory in both these works points to a development of this phenomenon in Latin bucolic poetry. Whereas Vir- gil’s Eclogues express a genuine anxiety with the preservation of Rome’s ancient customs and traditions in times of political turbulence, Calpurnius Siculus’s poems address issues of a different kind with the use of references to social memory. Virgil’s shepherds see their pastoral community disseminating: they start forgetting their lays or misremem- bering verses, indicating the author’s concern with Rome’s social memory and, thereby, with the prosperity and stability of the Res Publica. Calpurnius Siculus, on the other hand, has his herdsmen strive for the emperor’s patronage and a literary career in the big city, bored as they are by the countryside. They desire a larger, more cohesive and active urban community in which they and their songs will receive the acclaim they deserve and consequently live on in Rome’s social memory. Calpurnius Siculus’s poems are, however, in contrast to Virgil’s, no longer concerned with social memory in itself. Keywords: social memory, Eclogues, Virgil, Calpurnius Siculus 14 Paul Hulsenboom Abstrakt Niniejszy artykuł omawia rolę pamięci zbiorowej w poezji idyllicznej Wergiliusza i Kalpurniusza Sykulusa. Rezultaty porównania między odwołaniem się obu autorów do rzymskiej pamięci zbiorowej wskazują na rozwój tego tematu w łacińskiej poezji bu- kolicznej. -

The Ptolemies: an Unloved and Unknown Dynasty. Contributions to a Different Perspective and Approach

THE PTOLEMIES: AN UNLOVED AND UNKNOWN DYNASTY. CONTRIBUTIONS TO A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE AND APPROACH JOSÉ DAS CANDEIAS SALES Universidade Aberta. Centro de História (University of Lisbon). Abstract: The fifteen Ptolemies that sat on the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (the date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII) are in most cases little known and, even in its most recognised bibliography, their work has been somewhat overlooked, unappreciated. Although boisterous and sometimes unloved, with the tumultuous and dissolute lives, their unbridled and unrepressed ambitions, the intrigues, the betrayals, the fratricides and the crimes that the members of this dynasty encouraged and practiced, the Ptolemies changed the Egyptian life in some aspects and were responsible for the last Pharaonic monuments which were left us, some of them still considered true masterpieces of Egyptian greatness. The Ptolemaic Period was indeed a paradoxical moment in the History of ancient Egypt, as it was with a genetically foreign dynasty (traditions, language, religion and culture) that the country, with its capital in Alexandria, met a considerable economic prosperity, a significant political and military power and an intense intellectual activity, and finally became part of the world and Mediterranean culture. The fifteen Ptolemies that succeeded to the throne of Egypt between 305 B.C. (date of assumption of basileia by Ptolemy I) and 30 B.C. (death of Cleopatra VII), after Alexander’s death and the division of his empire, are, in most cases, very poorly understood by the public and even in the literature on the topic. -

The Greek World

THE GREEK WORLD THE GREEK WORLD Edited by Anton Powell London and New York First published 1995 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. Disclaimer: For copyright reasons, some images in the original version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 First published in paperback 1997 Selection and editorial matter © 1995 Anton Powell, individual chapters © 1995 the contributors All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Greek World I. Powell, Anton 938 Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data The Greek world/edited by Anton Powell. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Greece—Civilization—To 146 B.C. 2. Mediterranean Region— Civilization. 3. Greece—Social conditions—To 146 B.C. I. Powell, Anton. DF78.G74 1995 938–dc20 94–41576 ISBN 0-203-04216-6 Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-203-16276-5 (Adobe eReader Format) ISBN 0-415-06031-1 (hbk) ISBN 0-415-17042-7 (pbk) CONTENTS List of Illustrations vii Notes on Contributors viii List of Abbreviations xii Introduction 1 Anton Powell PART I: THE GREEK MAJORITY 1 Linear -

200 Bc - Ad 400)

ARAM, 13-14 (2001-2002), 171-191 P. ARNAUD 171 BEIRUT: COMMERCE AND TRADE (200 BC - AD 400) PASCAL ARNAUD We know little of Beirut's commerce and trade, and shall probably continue to know little about this matter, despite a lecture given by Mrs Nada Kellas in 19961. In fact, the history of Commerce and Trade relies mainly on both ar- chaeological and epigraphical evidence. As far as archaeological evidence is concerned, one must remember that only artefacts strongly linked with ceram- ics, i.e. vases themselves and any items, carried in amphoras, (predominantly, but not solely, liquids, can give information about the geographical origin, date and nature of such products. The huge quantities of materials brought to the light by recent excavations in Beirut should, one day, provide us with new evi- dence about importations of such products in Beirut, but we will await the complete study of this material, which, until today by no means provided glo- bal statistics valid at the whole town scale. The evidence already published still allows nothing more than mere subjective impressions about the origins of the material. I shall try nevertheless to rely on such impressions about that ma- terial, given that we lack statistics, and that it is impossible to infer from any isolated sherd the existence of permanent trade-routes and commercial flows. The results of such an inquiry would be, at present, worth little if not con- fronted with other evidence. On the other hand, it should be of great interest to identify specific Berytan productions among the finds from other sites in order to map the diffusion area of items produced in Beirut and the surrounding territory. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

Banbhore) (200 Bc to 200 Ad)

INTERNATIONAL TRADE OF SINDH FROM ITS PORT BARBARICON (BANBHORE) (200 BC TO 200 AD) BY M.H. PANHWAR This period covers the rule of Bactrian Greeks, Scythians, Parthians and Kushans in Sindh, rest of the present Pakistan and parts of India. The origins of the development of European trade in the Sindh and trade routes under notice go back to later part of the sixth century BC, and it involved continuous efforts over next seven centuries. (a) After Darius-I’s conquest of Gandhara and Sindhu, admiral Skylax (a Greek of Caryanda), made exploratory voyage down the Kabul and the Indus from Kaspapyrus or Kasyabapura (Peshawar) to the Sindh coast and thence along the Arabian coast to the Red Sea and Egypt in 518 BC, completing the journey in 2 1/2 years and returning to Iran in 514 BC. The voyage was meant to connect the South Asia with Egypt. Darius-I also restored Necho-II’s canal connecting the Nile with the Red Sea. Thus he made Egypt and not Mesopotamia the main line of communication between the Indian and the Mediterranean Oceans. Darius built ‘the Royal Road’ connecting various cities of the empire. It ran the distance of 1677 well-garrisoned miles from Euphesus to Susa. A much longer route than this was from Babylon to Ecbatans and from thence to Kabul, which was already connected with Peshawar. The great voyage of Skylax connected Peshawar with the Red Sea and Egypt, via the Indus and the Arabian Sea. The earlier Egyptian navigation under Pharaohs had purely utilitarian and limited objectives were in no way similar to the great historical voyages, like one by Skylax, for general exploration. -

Chemical and Morphological Studies Could Be Made of Polysomes of Lymphoid Tissue Cells During Response to Antigen Injection

THE NA TURE OF POLYSOMES ISOLATED FROM SPLEEN CELLS OF RATS STIMULATED BY ANTIGEN* BY MARIANO F. LA VIA, t ALBERT E. VATTER, WILLIAM S. HAMMOND,t AND PATRICIA V. NORTHUP DEPARTMENT OF PATHOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO MEDICAL CENTER, DENVER Communicated by Paul R. Cannon, November 7, 1966 Kern and co-workers' were the first to examine the molecular mechanism of im- munoglobulin synthesis and concluded that this process is similar to the synthesis of other proteins. Recently, lymphoid tissues have been studied by more refined electron microscopic2' I and biochemical techniques4- in an effort to examine details of the mechanism of synthesis of antibody. The data presented in many of these studies are difficult to reconcile with present models of polypeptide synthesis on polysomes. The current hypothesis is that the size of a fully functional polysome should be compatible with the size of the product of synthesis.7 Thus for L and H chains one would expect polysomes in the range of 7 and 15 ribosomes, respectively. The examination of polysomal units of immunoglobulin synthesis isolated from lymph node and spleen homogenates has been complicated by the presence of high- activity ribonucleases (RNases). These tissues seem to lack the RNase inhibitors present in liver cells.8 The contradictory results of experiments in this field might be due to endogenous RNases. On the other hand, synthesis of an antibody mole- cule might proceed differently from the model proposed for other polypeptides. The work reported here is the result of efforts to develop a system in which bio- chemical and morphological studies could be made of polysomes of lymphoid tissue cells during response to antigen injection.