Avi Final for Sending to the Uni Sep 19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCUMENTS on GERMAN FOREIGN POLICY ' 1918-1945 from Tbe Brcbt"Es of Tbe ~Erman Jforeign .Ministtl2

DOCUMENTS ON GERMAN FOREIGN POLICY ' 1918-1945 from tbe Brcbt"es of tbe ~erman jforeign .Ministtl2 Series D Volume I FROM NEURATH TO RIBBENTROP September 1 9 3 7 • September 19 3 8 LONDON HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE In June 1946 the British Foreign Office and the United States Department of State agreed jointly to publish documents from captured archives of the German Foreign Ministry and the Reich Chancellery. Although the main body of the captured archives goes back to the year 1867, it was decided· to limit the present publication to papers relating to the years after 1918, since the object of the publication was" to establish the record of German foreign policy preceding and du:ing World War II". The editorial work was to be performed " on the basis of the highest scholarly objectivity". The editors were to have complete freedom in the selection of the documents to be published. Publication was to begin and be concluded as soon as possible. In April1947 the French Government, having requested the right to participate in the project, accepted the terms of this agree ment. The documents covering the period from July 1936 to the outbreak of War in September 1939 have now been selected jointly by the three Allied Editorial Staffs. They comprise six volumes, and form the first and larger portion of Series D, which will carry the history of German foreign relations to the end of the Second World War. Volume I, the present volume, deals with Germany's foreign policy from the end of September 1937 to September 1938, covering particularly the seizure of Austria in March 1938. -

Measuring Participation Outcomes in Rehabilitation Medicine

Measuring participation outcomes in rehabilitation medicine Carlijn van der Zee Officieel_Carlijn.indd 1 25-6-2013 10:56:39 Cover Jan-Willem Duim, xiwel.nl Layout Renate Siebes, Proefschrift.nu Printed by Ridderprint, Ridderkerk ISBN 978-90-393-7003-2 © 2013 Carlijn van der Zee All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. The copyright of the articles that have been accepted for publication or that have already been published, has been transferred to the respective journals. Officieel_Carlijn.indd 2 25-6-2013 10:56:39 Measuring participation outcomes in rehabilitation medicine Het meten van participatie als uitkomst in de revalidatie (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. G.J. van der Zwaan, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 29 augustus 2013 des middags te 2.30 uur door Catharina Helena van der Zee geboren op 12 oktober 1980 te Gouda Officieel_Carlijn.indd 3 25-6-2013 10:56:39 Promotor: Prof.dr. F.J.G. Backx Co-promotor: Dr. M.W.M. Post De in het proefschrift beschreven studies zijn mogelijk gemaakt door financiële steun van de zorgverzekeraars AGIS, DSW en Avizo/Mezis, de Stichting Wetenschappelijk Fonds De Hoogstraat te Utrecht en Swiss Paraplegic Research. De totstandkoming van dit proefschrift werd mede mogelijk gemaakt door financiële steun van de Stichting Wetenschappelijk Fonds De Hoogstraat te Utrecht, De Hoogstraat Revalidatie, De Hoogstraat Orthopedietechniek, Sophia Revalidatie, de Libra Zorggroep, TulipMed, George In der Maur orthopedische schoentechniek en Biometrics te Almere. -

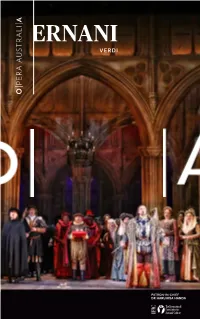

Ernani Program

VERDI PATRON-IN-CHIEF DR HARUHISA HANDA Celebrating the return of World Class Opera HSBC, as proud partner of Opera Australia, supports the many returns of 2021. Together we thrive Issued by HSBC Bank Australia Limited ABN 48 006 434 162 AFSL No. 232595. Ernani Composer Ernani State Theatre, Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) Diego Torre Arts Centre Melbourne Librettist Don Carlo, King of Spain Performance dates Francesco Maria Piave Vladimir Stoyanov 13, 15, 18, 22 May 2021 (1810-1876) Don Ruy Gomez de Silva Alexander Vinogradov Running time: approximately 2 hours and 30 Conductor Elvira minutes, including one interval. Carlo Montanaro Natalie Aroyan Director Giovanna Co-production by Teatro alla Scala Sven-Eric Bechtolf Jennifer Black and Opera Australia Rehearsal Director Don Riccardo Liesel Badorrek Simon Kim Scenic Designer Jago Thank you to our Donors Julian Crouch Luke Gabbedy Natalie Aroyan is supported by Costume Designer Roy and Gay Woodward Kevin Pollard Opera Australia Chorus Lighting Designer Chorus Master Diego Torre is supported by Marco Filibeck Paul Fitzsimon Christine Yip and Paul Brady Video Designer Assistant Chorus Master Paul Fitzsimon is supported by Filippo Marta Michael Curtain Ina Bornkessel-Schlesewsky and Matthias Schlesewsky Opera Australia Actors The costumes for the role of Ernani in this production have been Orchestra Victoria supported by the Concertmaster Mostyn Family Foundation Sulki Yu You are welcome to take photos of yourself in the theatre at interval, but you may not photograph, film or record the performance. -

New Europe College Black Sea Link Program Yearbook 2010-2011, 2011-2012

New Europe College Black Sea Link Program Yearbook 2010-2011, 2011-2012 DIANA DUMITRU IBRAHIM IBRAHIMOV NATALYA LAZAR OCTAVIAN MILEVSCHI ORLIN SABEV (ORHAN SALIH) VSEVOLOD SAMOKHVALOV STANISLAV SECRIERU OCTAVIAN ŢÎCU LIA TSULADZE TAMARA ZLOBINA Editor: Irina Vainovski-Mihai Copyright – New Europe College ISSN 1584-0298 New Europe College Str. Plantelor 21 023971 Bucharest Romania www.nec.ro; e-mail: [email protected] Tel. (+4) 021.307.99.10, Fax (+4) 021. 327.07.74 TAMARA ZLOBINA Born in 1982, in Ukraine “Kandydat nauk” (Ph.D. equivalent) in Philosophy, National Institute for Strategic Studies, Kyiv (2010) Dissertation: The role of cultural space in the development of the Ukrainian political nation Independent scholar, curator and art critic Research grants and curatorial residencies in Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus Participation in conferences and research seminars in Ukraine, Lithuania, Estonia, Poland, Hungary, Belgium, Georgia Articles and studies on contemporary art, gender studies, production of space, and nationalism in Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus THE VISA DENIAL CASE: CONTEMPORARY ART IN BELARUS, MOLDOVA, AND UKRAINE BETWEEN POLITICAL EMANCIPATION AND INTERNALIZATION OF COLONIAL GAZE Introduction The position of the contemporary art from Central and Eastern Europe in the global art world can be metaphorically described through the art work of Sándor Pinczehelyi called “Almost 30 Years 1973‑2002” (Hungary).1 The first part of it was produced in 1973. It represents the self portrait of a young man holding the hammer and the sickle in front of his face. His two hands are strictly crossed in front of his chest and his face is framed by the symbols of communist ideology. -

Representations of Social Media in Popular Discourse

REPRESENTATIONS OF SOCIAL MEDIA IN POPULAR DISCOURSE REPRESENTATIONS OF SOCIAL MEDIA IN POPULAR DISCOURSE By PAMELA INGLETON, B.A. (Hons), M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Pamela Ingleton, December 2017 McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2017) Hamilton, Ontario (English and Cultural Studies) TITLE: Representations of Social Media in Popular Discourse AUTHOR: Pamela Ingleton, B.A. (Hons) (Queen’s University), M.A. (McMaster University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Lorraine York NUMBER OF PAGES: ix, 248 ii Lay Abstract This sandwich thesis of works published from 2010 – 2017 considers how we talk and write about social media in relation to a variety of other concerns: authorship and popular fiction, writing and publishing, archives and everyday life, celebrity and the opaque morality of media promotion. The project addresses social networking platforms (primarily Twitter and Facebook) and those who serve and critique their interests (authors, readers, academics, “everyday people,” national archives, celebrities and filmmakers), often focusing on the “meta” of the media they take as their focus: “extratexts,” reviews and interviews, tweets about books and books about tweets, critical reception, etc. By examining writing on and about social media, this work offers an alternative, context-specific approach to new media scholarship that, in its examination of things said and unsaid, will help inform our contemporary understanding of social media and, by extension, our social media experience. iii Abstract This sandwich thesis of works published from 2010 – 2017 takes up the discursive articulation of “social media” as a mobilizing concept in relation to a variety of other concerns: authorship and popular fiction, writing and publishing, archives and everyday life, celebrity and the opaque morality of media promotion. -

Appendix B: a Literary Heritage I

Appendix B: A Literary Heritage I. Suggested Authors, Illustrators, and Works from the Ancient World to the Late Twentieth Century All American students should acquire knowledge of a range of literary works reflecting a common literary heritage that goes back thousands of years to the ancient world. In addition, all students should become familiar with some of the outstanding works in the rich body of literature that is their particular heritage in the English- speaking world, which includes the first literature in the world created just for children, whose authors viewed childhood as a special period in life. The suggestions below constitute a core list of those authors, illustrators, or works that comprise the literary and intellectual capital drawn on by those in this country or elsewhere who write in English, whether for novels, poems, nonfiction, newspapers, or public speeches. The next section of this document contains a second list of suggested contemporary authors and illustrators—including the many excellent writers and illustrators of children’s books of recent years—and highlights authors and works from around the world. In planning a curriculum, it is important to balance depth with breadth. As teachers in schools and districts work with this curriculum Framework to develop literature units, they will often combine literary and informational works from the two lists into thematic units. Exemplary curriculum is always evolving—we urge districts to take initiative to create programs meeting the needs of their students. The lists of suggested authors, illustrators, and works are organized by grade clusters: pre-K–2, 3–4, 5–8, and 9– 12. -

The Birthplace of Hockey Adam Gopnik Traces the Montreal Roots of Our Greatest Winter Sport

McG NeALUMw NI MAGAsZINE Moments that changed McGill McGill Daily turns 100 Anne-France Goldwater : arbitre vedette The birthplace of hockey Adam Gopnik traces the Montreal roots of our greatest winter sport FALL/WINTER 20 11 publications.mcgill.ca/mcgillnews “My“My groupgroup ratesrates savedsaved meme a lotlot ofof money.”moneyy..” – Miika Klemetti, McGill graduate Satisfied client since 2008 Insurance program recommended by the SeeSee howhow goodgood youryour quotequote cancan be.be. At TD Insurance Meloche Monnex, we know how important it is to save wherever you can. As a member of the McGill Alumni Association, you can enjoy preferred group rates and other exclusive privileges, thanks to ourour partnership with your association. You’ll also benefit fromom great coverage and outstanding service. At TD Insurance, we believe in making insurance easy to understand so you can choose your coverage with confidence. GetGet anan onlineonline quotequote atat www.melochemonnex.com/mcgillwww.melochemomonnex.com/mcgill oror callcall 1-866-352-61871-866-352-6187 MondayMonday toto Friday,Friday, 8 a.m.a.m. toto 8 p.m.p.m. SSaturday,aturday, 9 aa.m..m. ttoo 4 pp.m..m. The TD Insurance Meloche Monnex home and auto insurance pprogramg is underunderwritten byy SECURITY NAATIONALTIONAL INSURANCEINSURANCE COMPANY. The program is distributed by MelocheMeloche Monnex Insurance and Financial Services Inc. in Quebecebec and by Meloche Monnex Financiall Services Inc. in the rest off Canada. Due to pprovincial legislation,g our auto insurance program is not offered in British Coolumbia, Manitoba or Saskatchewan. *No purchaseh required.d Contest endsd on January 13, 2012. -

Winter: Five Windows on the Season PDF Book

WINTER: FIVE WINDOWS ON THE SEASON PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Adam Gopnik | 256 pages | 27 Sep 2011 | House of Anansi Press | 9780887849756 | English | Toronto, Canada, Canada Winter: Five Windows on the Season PDF Book Americans in Paris Amazon. Shelves: arts-literat-classics. I don't know where I came across this title, but I'm very glad I did. I need to read this at least twice more to absorb the layers of this dense text. We aim to create a safe and valuable space for discussion and debate. Much of Gopnik's quest is rooted in the joy of his own childhood imagination: if there were a heaven, he suggests, for him it would perpetually be 19 December; school is out, coloured lights are in the shops, there is ice underfoot and Christmas a week away. We use cookies to serve you certain types of ads , including ads relevant to your interests on Book Depository and to work with approved third parties in the process of delivering ad content, including ads relevant to your interests, to measure the effectiveness of their ads, and to perform services on behalf of Book Depository. Stafford Beer. He had previously authored several books on different topics, the most successful being Paris to the Moon , a collection of essays published in Performance and Analytics. That's pretty much my only complaint with this book. Adam Gopnik has been contributing to The New Yorker since A delightful, insightful, often humourous investigation into the modern Western idea of winter: what is the season, what does it mean to us, what has it meant to us in the past. -

Modes of Adaptation and Appropriation in the Hogarth Shakespeare Series

Trabajo de Fin de Máster en Estudios Literarios y Culturales Ingleses y su Proyección Social Modes of Adaptation and Appropriation in the Hogarth Shakespeare Series Autor: Mario Giménez Yuste Tutora: Dra. Marta Cerezo Moreno Facultad de Filología UNED Convocatoria general: junio 2019 Curso: 2018-19 Modes of Adaptation and Appropriation in the Hogarth Shakespeare Series Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 2 2. Theoretical Framework .................................................................................................. 4 2.1. Adaptation and Appropriation ................................................................................... 4 3. The Hogarth Series .................................................................................................... 14 3.1. Critical Reception ..................................................................................................... 14 3.2. A Brief Consideration of the Seven Novels ............................................................... 16 3.3. Selection Criteria ...................................................................................................... 20 4. The Chosen Novels ........................................................................................................ 21 4.1. Dunbar ...................................................................................................................... 21 4.1.1. Critical Reception ............................................................................................. -

Magazin Treffen Junger Autoren 2017

Berliner Festspiele 32. Treffen junger Autoren 16. bis 20. November 2017 Inhaltsverzeichnis 3 Vorwort 74 Campus Ein Fenster in eine neue 76 Praxis Welt entdecken – 83 Dialog von Christina Schulz 85 Fokus 86 Spezial 4 Bühne 6 Lynn Sophie Guldin 90 Blog 8 Veronika Artibilova 10 Fanny Haimerl 92 Forum 12 Marlena Wessollek 95 Praxis 14 Amelie Schmid 95 Dialog 16 Rosa Engelhardt 18 Paloma Solazzo 96 Jury 20 Stefan Gruber 99 Anthologie 22 Pauline van Gemmern 100 Kuratorium 24 Kerstin Uebele 101 Statistik 26 Sandro Huber 102 Bundeswettbewerbe 28 Josefin Fischer 103 Impressum 1 30 Ansgar Riedißer 104 Kalendarium 32 Lea Wahode 34 Farukh Sauerwein 36 Miedya Mahmod 38 Rebecca Heims 40 Laura Herman 42 Moritz Schlenstedt 44 Jelin Katz 48 Essay 51 Letters from Literature – von Priya Basil 56 Wer bin ich, wenn ich schreibe? – von Thomas Freyer, Olivia Wenzel, Max Wallenhorst, Kristo Šagor, Kirsten Fuchs und Reihaneh Youzbashi Dizaji 62 Verhandlungen über das Unverhandelbare? – Die Gerichtszeichnungen von Marina Naprushkina 2 Treffen junger Autoren junger Treffen Ein Fenster in eine neue Welt entdecken In ihrer Eröffnungsrede für das 13. internationale literaturfestival berlin sagte Taiye Selasi über Literatur: „Jedes Mal, wenn wir ein Buch in die Hand nehmen, löschen wir unsere persönlichen Grenzen aus. Wir überschreiten die Markierun- gen unseres Selbst und betreten das unbekannte Territorium des Anderen. Nach den ersten Augenblicken der Desorientiertheit merken wir, dass wir zu Hause sind.“ Es ist eine sehr eindrückliche Beschreibung für das, was in beson- deren Momenten des Lesens geschehen kann, und wonach man sich beim Lesen vielleicht sehnt – einen unbekannten Weg einzuschlagen, ein Fenster in eine neue Welt zu entdecken oder sich auf eine unverhoffte Begebenheit einzu- lassen. -

Moabit Mountain College Keine Zeit Für Kunst 11.09. – 31.10.2020 Eine

Keine Zeit für Kunst 11.09. – 31.10.2020 Eine Ausstellung mit Arbeiten von / An exhibition with works by Marina Naprushkina & Moabit Mountain College Pressemappe / Press Kit Inhalt Allgemeine Presseinformationen / General Press Information Ein Gespräch zwischen / A conversation between Marina Naprushkina & Nataša Ilić Biografien/ biographies Marina Naprushkina & Moabit Mountain College Galerie Wedding Raum für zeitgenössische Kunst Bezirksamt Mitte von Berlin Amt für Weiterbildung und Kultur Fachbereich Kunst, Kultur und Geschichte Pressekontakt Malte Pieper T (030) 9018 42385 [email protected] Müllerstraße 146 – 147 13353 Berlin www.galeriewedding.de www.facebook.com/galeriewedding www.instagram.com/galeriewedding Allgemeine Presseinformationen Berlin, 10.09.2020 Keine Zeit für Kunst 11.09. bis 31.10.2020 Eine Ausstellung von Marina Naprushkina & Moabit Mountain College kuratiert von Nataša Ilić Im Rahmen von Sos (Soft Solidarity), konzipiert von Nataša Ilić und Solvej Helweg Ovesen Erö#nung am 10.09.2020 von 19 – 22 Uhr mit Moabit Mountain College Küche: Mazen Alsawaf Musik: Marsa Band Keine Zeit für Kunst ist keine gewöhnliche Ausstellung, sondern vielmehr ein künstlerisches Statement der Künstlerin Marina Naprushkina und des Moabit Mountain College (MMC), das über die Arbeitsbedingungen in der Kunstwelt und darüber hinaus reflektiert. Die Ausstellungserö!nung findet am 10. September 2020 von 19 bis 22 Uhr in der Galerie Wedding – Raum für zeitgenössische Kunst statt. Für Naprushkina und das Moabit Mountain College, das auf der langjährigen Arbeit der Berliner Initiative Neue Nachbarschaft/Moabit aufbaut, bildet die Kunst eine Grundlage für alle anderen Disziplinen. Neue Nachbarschaft/Moabit ist ein Geflüchteten- und Nachbarschaftsprojekt, das zu einer der größten Initiativen dieser Art in Berlin herangewachsen ist und eine starke Gemeinschaft von Geflüchteten, Menschen mit Migrationsgeschichte und Nachbar*innen aufgebaut hat. -

RAM PUB SPRNG-15 FINAL.Indd

publications + distribution spring 2015 spring 2015 Architecture 5 Art + Culture 8 Design + Graphics 29 Photography 34 Theory + Literary Arts 40 Previously Announced 50 RAM ORDeR + TRADe InfORMATIOn 52 rampub.com Art Architecture + Culture Highlights XXII CEMEX BUILDING AWARD Produced now for over 20 years, this comprehensively illustrated volume documents the winners of the 2015 renowned building award sponsored by international concrete, cement and aggregates giant CeMeX, based in Mexico. Chosen by a prestigious jury of 17 international and domestic architects, engineers and designers, the prize-winners span 13 categories, from single-family and multi-unit residential (both conventional and low-income) to commercial and mixed-use, accessibility, social impact, urbanism, infrastructure, innovation in techniques and construction processes and sustainability. Also awarded is a Lifetime Achievement Award, this year given to Spanish architect Carlos ferrater i Lambarri. The book is an indispensible reference on current architecture and building technologies for libraries, architects, designers and engineers. A stunning publication filled with full-color plates and informative essays. January 2015, english & Spanish ARQUIe n , MeXICO Hardcover, 9 x 11 ¼ inches CeMeX, MeXICO 284 pp, extensive color ISBn: 978-607-7784-69-2 Retail price: $42.50 49 CITIES WORKac (ed.) The much-in-demand 49 Cities, first published by Storefront for Art & Architecture, the internationally recognized nYC center for alternative thinking in art and architecture, is now available in its third edition. This fascinating compilation of “fantastic projections” by architects and planners dreaming of better and different cities ranges from 500 B.C. to the present. With every plan, radical visions were proposed, embodying not only desires but also fears and anxieties of the time.