Rice in the Filipino Diet and Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GML QUARTERLY JANUARY-MARCH 2012 Magazine District 3800 MIDYEAR REVIEW

ROTARY INTERNATIONAL DISTRICT 3800 GML QUARTERLY JANUARY-MARCH 2012 Magazine dISTRICT 3800 MIDYEAR REVIEW A CELEBRATION OF MIDYEAR SUCCESSES VALLE VERDE COUNTRY CLUB JANUARY 21, 2012 3RD QUARTER CONTENTS ROTARY INTERNATIONAL District 3800 The Majestic Governor’s Message 3 Rafael “Raffy” M. Garcia III District Governor District 3800 Midyear Review 4 District Trainer PDG Jaime “James” O. Dee District 3800 Membership Status District Secretary 6 PP Marcelo “Jun” C. Zafra District Governor’s Aide PP Rodolfo “Rudy” L. Retirado District 3800 New Members Senior Deputy Governors 8 PP Bobby Rosadia, PP Nelson Aspe, February 28, 2012 PP Dan Santos, PP Luz Cotoco, PP Willy Caballa, PP Tonipi Parungao, PP Joey Sy Club Administration Report CP Marilou Co, CP Maricris Lim Pineda, 12 CP Manny Reyes, PP Roland Garcia, PP Jerry Lim, PP Jun Angeles, PP Condrad Cuesta, CP Sunday Pineda. District Service Projects Deputy District Secretary 13 Rotary Day and Rotary Week Celebration PP Rudy Mendoza, PP Tommy Cua, PP Danny Concepcion, PP Ching Umali, PP Alex Ang, PP Danny Valeriano, The RI President’s Message PP Augie Soliman, PP Pete Pinion 15 PP John Barredo February 2011 Deputy District Governor PP Roger Santiago, PP Lulu Sotto, PP Peter Quintana, PP Rene Florencio, D’yaryo Bag Project of RCGM PP Boboy Campos, PP Emy Aguirre, 16 PP Benjie Liboro, PP Lito Bermundo, PP Rene Pineda Assistant Governor RY 2011-2012 GSE Inbound Team PP Dulo Chua, PP Ron Quan, PP Saldy 17 Quimpo, PP Mike Cinco, PP Ruben Aniceto, PP Arnold Divina, IPP Benj Ngo, District Awards Criteria PP Arnold Garcia, PP Nep Bulilan, 18 PP Ramir Tiamzon, PP Derek Santos PP Ver Cerafica, PP Edmed Medrano, PP Jun Martinez, PP Edwin Francisco, PP Cito Gesite, PP Tet Requiso, PP El The Majestic Team Breakfast Meeting Bello, PP Elmer Baltazar, PP Lorna 19 Bernardo, PP Joy Valenton, PP Paul January 2011 Castro, Jr., IPP Jun Salatandre, PP Freddie Miranda, PP Jimmy Ortigas, District 3800 PALAROTARY PP Akyat Sy, PP Vic Esparaz, PP Louie Diy, 20 PP Mike Santos, PP Jack Sia RC Pasig Sunrise PP Alfredo “Jun” T. -

District 3800 Rotary Academy PP Marcelo “Jun” C

ROTARY INTERNATIONAL DISTRICT 3800 GOVERNOR’S MONTHLY OCTOBER 2011 LETTER DISTRICT GOVERNOR RAFAEL GARCIA iII and dgl minda with the majestic team at the oktober-fiesta OCTOBER 2011 CONTENTS ROTARY INTERNATIONAL District 3800 The Majestic Governor’s Message Rafael “Raffy” M. Garcia III 3 District Governor District Trainer PDG Jaime “James” O. Dee District Secretary District 3800 Rotary Academy PP Marcelo “Jun” C. Zafra 4 District Governor’s Aide PP Rodolfo “Rudy” L. Retirado Senior Deputy Governors PP Bobby Rosadia, PP Nelson Aspe, District 3800 October Fiesta PP Dan Santos, PP Luz Cotoco, PP Willy 8 Caballa, PP Tonipi Parungao, PP Joey Sy October 08, 2011 CP Marilou Co, CP Maricris Lim Pineda, CP Manny Reyes, PP Roland Garcia, PP Jerry Lim, PP Jun Angeles, PP Condrad Cuesta, CP Sunday Pineda. District 3800 RYLA 2011 Deputy District Secretary 10 PP Rudy Mendoza, PP Tommy Cua, October 21 -23, 2011 PP Danny Concepcion, PP Ching Umali, PP Alex Ang, PP Danny Valeriano, PP Augie Soliman, PP Pete Pinion PP John Barredo ART FROM THE HEART Deputy District Governor 12 CP Mila Puyat/ RC Greater Mandaluyong PP Roger Santiago, PP Lulu Sotto, PP Peter Quintana, PP Rene Florencio, PP Boboy Campos, PP Emy Aguirre, PP Benjie Liboro, PP Lito Bermundo, PP Rene Pineda District 3800 Duckpin Bowling Fellowship Assistant Governor PP Dulo Chua, PP Ron Quan, PP Saldy 13 MP Rod Macalinao/ RC Pasig North Quimpo, PP Mike Cinco, PP Ruben Aniceto, PP Arnold Divina, IPP Benj Ngo, PP Arnold Garcia, PP Nep Bulilan, PP Ramir Tiamzon, PP Derek Santos District Secretary’s Report PP Ver Cerafica, PP Edmed Medrano, 14 PP Jun Martinez, PP Edwin Francisco, DS Marcelo “Jun” Zafra, Jr PP Cito Gesite, PP Tet Requiso, PP El Bello, PP Elmer Baltazar, PP Lorna Bernardo, PP Joy Valenton, PP Paul Castro, Jr., IPP Jun Salatandre, District 3800 Attendance Report PP Freddie Miranda, PP Jimmy Ortigas, 15 PP Akyat Sy, PP Vic Esparaz, PP Louie Diy, August, 2011 PP Mike Santos, PP Jack Sia PP Alfredo “Jun” T. -

REAL.ESTATE Cpdprogram.Pdf

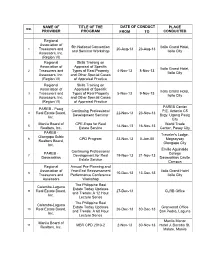

NAME OF TITLE OF THE DATE OF CONDUCT PLACE NO. PROVIDER PROGRAM FROM TO CONDUCTED Regional Association of 5th National Convention Iloilo Grand Hotel, 1 Treasurers and 20-Aug-13 23-Aug-13 and Seminar Workshop Iloilo City Assessors, Inc. (Region VI) Regional Skills Training on Association of Appraisal of Specific Iloilo Grand Hotel, 2 Treasurers and Types of Real Property 4-Nov-13 8-Nov-13 Iloilo City Assessors, Inc. and Other Special Cases (Region VI) of Appraisal Practice Regional Skills Training on Association of Appraisal of Specific Iloilo Grand Hotel, 3 Treasurers and Types of Real Property 5-Nov-13 9-Nov-13 Iloilo City Assessors, Inc. and Other Special Cases (Region VI) of Appraisal Practice PAREB Center PAREB - Pasig Continuing Professional P.E. Antonio C5 4 Real Estate Board, 22-Nov-13 23-Nov-13 Development Seminar Brgy. Ugong Pasig Inc. City Manila Board of CPE-Expo for Real World Trade 5 14-Nov-13 16-Nov-13 Realtors, Inc. Estate Service Center, Pasay City PAREB - Traveler's Lodge, Olongapo Subic 6 CPD Program 23-Nov-13 0-Jan-00 Magsaysay Realtors Board, Olongapo City Inc. Emilio Aguinaldo Continuing Professional PAREB - College 7 Development for Real 19-Nov-13 21-Nov-13 Dasmariñas Dasmariñas Cavite Estate Service Campus Regional Annual Pre-Planning and Association of Year-End Reassessment Iloilo Grand Hotel 8 10-Dec-13 13-Dec-13 Treasurers and Performance Conference Iloilo City Assessors Workshop The Philippine Real Calamba-Laguna Estate Today Updates 9 Real Estate Board, 27-Dec-13 CLRB Office and Trends: A 12 Hour Inc. -

Clemente C. Morales Family Salinas, California

The Filipino American Experience Research Project Copyright © October 3, 1998 The Filipino American Experience Research Project Clemente C. Morales Family Salinas, California Edited by Alex S. Fabros, Jr., The Filipino American Experience Research Project is an independent research project of The Filipino American National Historical Society Page 1 The Filipino American Experience Research Project Copyright © October 3, 1998 The Filipino American Experience Research Project Copyright (c) October 3, 1998 by Alex S. Fabros, Jr. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. Published in the United States by: The Filipino American Experience Research Project, Fresno, California. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 95-Pending First Draft Printing: 08/05/98 For additional information: The Filipino American Experience Research Project is an independent project within The Filipino American National Historical Society - FRESNO ALEX S. FABROS, JR. 4199 W. Alhambra Street Fresno, CA 93722 209-275-8849 The Filipino American Experience Research Project-SFSU is an independent project sponsored by Filipino American Studies Department of Asian American Studies College of Ethnic Studies San Francisco State University 1600 Holloway Avenue San Francisco, CA 94132 415-338-6161 (Office) 415-338-1739 (FAX) Page 2 The Filipino American Experience Research Project Copyright © October 3, 1998 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................. -

State Visit Further Elevates Relations

4 The Japan Times Wednesday, June 3, 2015 Philippine president’s visit State Visit further elevates relations ing root, and future prospects Organization (JeTRO). This But the strength of Philip- Japan in 2015 and beyond. For tually beneficial ties between are seen to further improve trend should strengthen and pine-Japan relations covers a their part, Japanese tourists the Republic of the Philippines under the bold policies and persist, as the two countries tap far broader sphere. In the polit- have demonstrated great en- and Japan readily emerge to structural and regulatory re- and optimize their many syner- ical-security arena, the two thusiasm for the Philippines, form one of the closest partner- forms being resolutely pursued gies and draw on the Philip- countries have also been stra- with its unrivaled beauty, rich ships in the Asia Pacific region. by the Abe government. pines’ expected strong tegic partners in the truest culture and proximity to Japan. President Aquino’s visit to Japan The Philippines’ surging eco- long-term growth. President sense, collaborating bilaterally Japanese tourists to the Philip- is the latest affirmation yet of nomic fortunes and Japan’s aquino’s administration’s own and in the context of regional pines reached 463,744 in 2014, this hallowed tradition. own sure steps toward econom- reforms have placed the Philip- frameworks to advance mutual a 6.9 percent increase. The Phil- With the bilateral relation- ic revival combine to create pines in an excellent position to interests, and to respond to ippines is now setting its sights ship set to mark 60 years of re- valuable opportunities for both attract both present and future common and complex chal- on breaching the half-million lations in 2016, President countries to derive substantial waves of Japanese FdI inflows. -

( Mabuhay Lanes ) Alternate Routes for EDSA

Republic of the Philippines Office of the President Alternate Routes for EDSA ( Mabuhay Lanes ) Alternate Routes For EDSA MABUHAY LANES for Private Vehicles from North to South Route 1: From Epifanio Delos Santos Avenue (EDSA): Turn right at West Avenue, right at Quezon Avenue, U-turn near Magbanua, right at Timog, right at T. Morato, right at E. Rodriguez, left at Gilmore, straight to Granada , right to Santolan Road or right at N. Domingo, left at Pinaglabanan, right at P. Guevarra, left at L. Mencias, right at Shaw Blvd., left at Acacia Lane, right at F. Ortigas, left at P. Cruz, left at F. Blumentrit, left at Coronado, take Mandaluyong - Makati Bridge to destination. Route 1a: From Epifanio Delos Santos Avenue (EDSA): Turn right at Scout Borromeo, left at Scout Ybardolaza / Scout Torillo / Scout T. Morato / Scout Tuazon or Scout Tobias, right at E. Rodriguez, left at Gilmore, straight to Granada , right to Santolan Road or right at N. Domingo, left at Pinaglabanan, right at P. Guevarra, left at L. Mencias, right at Shaw Blvd., left at Acacia Lane, right at F. Ortigas, left at P. Cruz, left at F. Blumentrit, left at Coronado, take Mandaluyong - Makati Bridge to destination. Route 2: From Epifanio Delos Santos Avenue (EDSA): Turn right at West Avenue, right at Del Monte Ave., left at Sto. Domingo or Biak na Bato, right at Amoranto , left at Banawe or D. Tuazon, right at Maria Clara or Dapitan to destination. Route 3: From North Luzon Expressway : Exit at Mindanao Avenue Access Ramp, right at Mindanao Ave., left at Congressional, right at Luzon Avenue, take Bridge crossing Commonwealth Avenue, Katipunan Avenue, C-5 to destination. -

2014 Accomplishment Report

2014 ACCOMPLISHMENT REPORT INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND/OR CONSUMER FAIRS PROJECT DESCRIPTION INPUT / OUTPUT / RECOMMENDATION Name of Event: ASEAN Tourism Forum (ATF) Input: Venue: Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia Approved Budget: Php 14,997,830.00 Inclusive Dates: 16 to 23 January 2014 Acquired a 216 sq. m. Phil. Pavilion featuring the major tourist destinations TPB distributed general destination brochures. Brief Description: TPB placed an advertisement in TTG Show Daily. ATF is a cooperative regional effort to promote the Association of Southeast Asian Hosted the Philippine Late Night Function Nations (ASEAN) region as one tourist destination where Asian hospitality and Conducted a raffle draw during the hosted dinner cultural diversity are at its best. This annual event involves all the tourism industry sectors of ten (10) member nations of ASEAN. Output: The booth accommodated a total of forty one (41) Philippine delegates from ATF also provides a platform for the selling and buying of regional individual tourism twenty three (23) private sector companies – sixteen (16) properties (hotels and products of ASEAN member countries, through the 3-day TRAVEX event. resorts) and seven (7) travel agents, and five (5) DOT Regional directors representing the BIMP EAGA Region. The Phil. delegation members gathered new contacts which they could develop into potential sales of wholesale Phil. Travel products. Whole page interview with Secretary Jimenez published in the Daily’s first issue Full Page ad on Chocolate Hills published on the Daily’s 2nd, 3rd and 4th issues TPB set appointments with a total of 29 buyers mostly FITs and general leisure agents. Nine of them were walk-in buyers. -

My Dear Global Family of Rotary, Everybody Deserves

RY 2010 - 2011 No. 5 November 2010 THE ROTARY FOUNDATION MONTH My Dear Global Family of Rotary, Everybody deserves congratulations. On our fifth month, we have accomplished so much already and if everything will proceed as planned, we will finish with most of our goals before the end of the year. The month of November is designated as The Rotary Foundation Month. We will celebrate The Rotary Foundation Month with so many activities relating to The Rotary Foundation. I urge all of the clubs in our district to focus on The Rotary Foundation and devote special features in your respective club bulletins about our Foundation. I also urge all of the generous Rotarians to give to the Foundation and make all of the clubs in our district as EREY Clubs. Last year, there were only two clubs who made it in the list of EREY Clubs. This year, our goal is to ask all clubs (100%) to give to the Foundation and 80% of the clubs to become EREY Clubs. Even with TRF, we want our clubs to become bigger, better and bolder. The highlight of the month long celebration is the Annual Giving Dinner (TRF Banquet) to be held on November 27, 2010 at Ruby Ballroom A and B of the Crown Plaza Galleria Hotel. This will be strictly formal. The Host Club is RC Mandaluyong and the Event Chair is PP Louie Diy. All Global Presidents and District Officers and their Spouses are required to attend. We will honour in this annual event all new Paul Harris Fellows (PHF), the new and continuing multiple PHF, the new Major Donors and the continuing Major Donors. -

The Commission on Elections from Aquino to Arroyo

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is with deep gratitude to IDE that I had a chance to visit and experience Japan. I enjoyed the many conversations with researchers in IDE, Japanese academics and scholars of Philippines studies from various universities. The timing of my visit, the year 2009, could not have been more perfect for someone interested in election studies. This paper presents some ideas, arguments, proposed framework, and historical tracing articulated in my Ph.D. dissertation submitted to the Department of Political Science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. I would like to thank my generous and inspiring professors: Paul Hutchcroft, Alfred McCoy, Edward Friedman, Michael Schatzberg, Dennis Dresang and Michael Cullinane. This research continues to be a work in progress. And while it has benefited from comments and suggestions from various individuals, all errors are mine alone. I would like to thank the Institute of Developing Economies (IDE) for the interest and support in this research project. I am especially grateful to Dr. Takeshi Kawanaka who graciously acted as my counterpart. Dr. Kawanaka kindly introduced me to many Japanese scholars, academics, and researchers engaged in Philippine studies. He likewise generously shared his time to talk politics and raise interesting questions and suggestions for my research. My special thanks to Yurika Suzuki. Able to anticipate what one needs in order to adjust, she kindly extended help and shared many useful information, insights and tips to help me navigate daily life in Japan (including earthquake survival tips). Many thanks to the International Exchange and Training Department of IDE especially to Masak Osuna, Yasuyo Sakaguchi and Miyuki Ishikawa. -

The New District 3800 Governor Rafael M. Garcia III and Family

RI DIsTRIcT 3800 GML QUARTERLY July 2011 MAGAzInE The New District 3800 Governor Rafael M. Garcia III and Family ROTARY INTERNATIONAL JULY 2011 CONTENTS District 3800 The Governor’s Inaugural Speech The Governor’s Inaugural Speech (District Handover Ceremonies) Rafael “Raffy” M. Garcia III 3 (District Handover Ceremonies) District Governor Majestic Governor Rafael M. “Raffy” Garcia III LET ME TELL YOU WHO I AM District Trainer 6 PDG Jaime “James” O. Dee (Personal Information of DG Raffy Garcia III) District Secretary PP Marcelo “Jun” C. Zafra The District Handover and Induction Senior Deputy Governors Immediate Past District Governor Jun Farcon and his God's Gift, Lady PP Bobby Rosadia, PP Nelson Aspe, Zeny, Immediate Past PCRG Chair, Incoming Philippine Rotary Magazine 10 PP Dan Santos, PP Luz Cotoco, PP Willy Ceremonies (World Trade Center - 02 July 2011) Caballa, PP Tonipi Parungao, PP Joey Sy Foundation Chair, my Leading Governor and Trainor James Dee and his CP Marilou Co, CP Maricris Lim Pineda, Valentine Elena, Past District Governors and their lovely spouses, My beautiful and ever loving wife Minda, CP Manny Reyes, PP Roland Garcia, PP and my family. Global Presidents and District Officers, Majestic Presidents, District Officers, Rotarians from The Activities of the District Governor Jerry Lim, PP Jun Angeles, PP Condrad 13 Pre- Rotary Year 2011-2012 Cuesta, CP Sunday Pineda. the irreverent, independent republic of the Rotary Club of Pasig, Fellow Rotarians, Distinguished Guests, Deputy District Secretary Ladies and Gentlemen: PP Rudy Mendoza, PP Tommy Cua, RI Mandated District Training & Seminar PP Danny Concepcion, PP Ching Umali, 16 PP Alex Ang, PP Danny Valeriano, Good Evening: Pre- Rotary Year 2011-2012 PP Augie Soliman, PP Pete Pinion PP John Barredo I am truly honored to stand here before you ready to serve as Governor for District 3800 for the Rotary Year Deputy District Governor PP Roger Santiago, PP Lulu Sotto, 2011-2012. -

The American Colonial and Contemporary Traditions

THE AMERICAN COLONIAL AND CONTEMPORARY TRADITIONS The American tradition in Philippine architecture covers the period from 1898 to the present, and encompasses all architectural styles, such as the European styles, which came into the Philippines during the American colonial period. This tradition is represented by churches, schoolhouses, hospitals, government office buildings, commercial office buildings, department stores, hotels, movie houses, theaters, clubhouses, supermarkets, sports facilities, bridges, malls, and high-rise buildings. New forms of residential architecture emerged in the tsalet, the two-story house, and the Spanish-style house. The contemporary tradition refers to the architecture created by Filipinos from 1946 to the present, which covers public buildings and private commercial buildings, religious structures, and domestic architecture like the bungalow, the one-and-a-half story house, the split-level house, the middle-class housing and the low-cost housing project units, the townhouse and condominium, and least in size but largest in number, the shanty. History The turn of the century brought, in the Philippines, a turn in history. Over three centuries of Spanish rule came to an end, and five decades of American rule began. The independence won by the Philippine Revolution of 1896 was not recognized by Spain, nor by the United States, whose naval and military forces had taken Manila on the pretext of aiding the revolution. In 1898 Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States, and after three years of military rule the Americans established a civil government. With a new regime came a new culture. The English language was introduced and propagated through the newly established public school system. -

Philippines People Power

v People Power in the Philippines February 22-25, 1986 January 16-20, 2001 April 25-May 1, 2001 The1986 Philippines Uprising: People Power 1 £ For five days in February 1986, hundreds of thousands of people gathered at the intersection of Ortigas Avenue and Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA). They helped overthrow Ferdinand Marcos, dictator for over 20 years. Ferdinand Marcos £ Ferdinand Marcos was the tenth president of the Philippines £ His term lasted from December 30, 1965 to February 25, 1986. £ To keep himself in power, he implemented martial law and built an authoritarian regime. Ferdinand Marcos •President 1965-1986 •1st president to be reelected •1972 Declares martial law •1983: had Ninoy Aquino assassinated •1985: pressured to have snap elections •1986: lost elections “Black Friday” £Six people killed by police attack on protests near Malacañang presidential palace Artists One estimate put the number of theater groups at 400 by 1987. Martyrs Torture under Marcos The Opposition Ferdinand Marcos’ main opponent was Benigno Aquino. Known as “Ninoy” he was a leading opposition politician. Aquino in Newton, Massachusetts £ Ferdinand Marcos faced a growing problem. He had to find a way to suppress Benigno Aquino. £ To get rid of Aquino, Marcos declared martial law in 1972 and imprisoned Aquino on murder charges. £ In1978, from his prison cell, Ninoy was allowed to take part in the elections for Interim Batasang Pambansa (Parliament). £ Aquino was sentenced to death in 1977, but because of a heart problem he was sent into exile for medical treatment in the United States in 1980. The Return £ After three years of exile in the US, Benigno Aquino made an attempt to enter the Philippines.