The American Colonial and Contemporary Traditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 PHILIPPINE CINEMA HERITAGE Summita Report

2013 PHILIPPINE CINEMA HERITAGE SUMMIT a report Published by National Film Archives of the Philippines Manila, 2013 Executive Offi ce 26th fl r. Export Bank Plaza Sen Gil Puyat Ave. cor. Chino Roces, Makati City, Philippines 1200 Phone +63(02) 846 2496 Fax +63(02) 846 2883 Archive Operations 70C 18th Avenue Murphy, Cubao Quezon City, Philippines 1109 Phone +63 (02) 376 0370 Fax +63 (02) 376 0315 [email protected] www.nfap.ph The National Film Archives of the Philippines (NFAP) held the Philippine Cinema Heritage Summit to bring together stakeholders from various fi elds to discuss pertinent issues and concerns surrounding our cinematic heritage and plan out a collaborative path towards ensuring the sustainability of its preservation. The goal was to engage with one another, share information and points of view, and effectively plan out an inclusive roadmap towards the preservation of our cinematic heritage. TABLE OF CONTENTS PROGRAM SCHEDULE ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION 2, COLLABORATING TOWARDS 6 23 SUSTAINABILITY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY NOTES ON 7 24 SUSTAINABILITY OPENING REMARKS ANALYSIS AND RECOMMENDATIONS in the wake of the 2013 Philippine Cinema 9 26 Heritage Summit ARCHITECTURAL CLOSING REMARKS 10 DESIGN CONCEPT 33 NFAP REPORT SUMMIT EVALUATION 13 2011 & 2012 34 A BRIEF HISTORY OF PARTICIPANTS ARCHIVAL ADVOCACY 14 FOR PHILIPPINE CINEMA 35 ROUNDTABLE DISCUSSION 1, PHOTOS ASSESSING THE FIELD: REPORTS FROM PHILIPPINE A/V ARCHIVES 21 AND STAKEHOLDERS 37 A BRIEF HISTORY OF ARCHIVAL ADVOCACY FOR PHILIPPINE CINEMA1 Bliss Cua Lim About the Author: Bliss Cua Lim is Associate Professor of Film and Media Studies and Visual Studies at the University of California, Irvine and a Visiting Research Fellow in the Center for Southeast Asian Studies at Kyoto University. -

Jean Judith Xavier

Jean Judith Xavier ICACM International Casting & Creative Management Sydney, NSW 2010 Michael Turkic: +61 481 085 972 William Le (text): +61 405 539 752 E: [email protected] W: http://www.icacm.com.au Biography Jean Judith Javier is a singer, musical theatre performer and a film actor, who is unstoppable in bringing her heart to her audience, she draws courage from them. As a soprano, Jean Judith sings for opera and musical theatre but never limits her capacity by performing pieces from world arts songs. As a film actor, her roles are unconventional that manifest her embodied inner strength but mystical persona. She learns how to sing at an early age of nine performing in the church and villages. Coming from a humble beginning, Jean Judith captures the skill of fine singing from her mother and her sensitivity for arts was nurtured by being deeply connected to the expressive musical cultures of the Philippines, her motherland. Her tenacity to work as a full-time actor and the faith she puts to her craft gave her opportunities to perform in cities and provinces in the Philippines and South and East Asian countries like Korea, Indonesia, Macau, Hong Kong, Taiwan and various cities in China. She assumed self-title roles from many original musicales that have had impacted the history of Philippine contemporary theatre. In opera, she played Sisa for “Noli Me Tangere: The Opera”, a difficult role. But her portrayal of the most iconic Philippine fictive character and deranged woman captures her audience giving her standing ovations and critical acclaim from critics. -

GML QUARTERLY JANUARY-MARCH 2012 Magazine District 3800 MIDYEAR REVIEW

ROTARY INTERNATIONAL DISTRICT 3800 GML QUARTERLY JANUARY-MARCH 2012 Magazine dISTRICT 3800 MIDYEAR REVIEW A CELEBRATION OF MIDYEAR SUCCESSES VALLE VERDE COUNTRY CLUB JANUARY 21, 2012 3RD QUARTER CONTENTS ROTARY INTERNATIONAL District 3800 The Majestic Governor’s Message 3 Rafael “Raffy” M. Garcia III District Governor District 3800 Midyear Review 4 District Trainer PDG Jaime “James” O. Dee District 3800 Membership Status District Secretary 6 PP Marcelo “Jun” C. Zafra District Governor’s Aide PP Rodolfo “Rudy” L. Retirado District 3800 New Members Senior Deputy Governors 8 PP Bobby Rosadia, PP Nelson Aspe, February 28, 2012 PP Dan Santos, PP Luz Cotoco, PP Willy Caballa, PP Tonipi Parungao, PP Joey Sy Club Administration Report CP Marilou Co, CP Maricris Lim Pineda, 12 CP Manny Reyes, PP Roland Garcia, PP Jerry Lim, PP Jun Angeles, PP Condrad Cuesta, CP Sunday Pineda. District Service Projects Deputy District Secretary 13 Rotary Day and Rotary Week Celebration PP Rudy Mendoza, PP Tommy Cua, PP Danny Concepcion, PP Ching Umali, PP Alex Ang, PP Danny Valeriano, The RI President’s Message PP Augie Soliman, PP Pete Pinion 15 PP John Barredo February 2011 Deputy District Governor PP Roger Santiago, PP Lulu Sotto, PP Peter Quintana, PP Rene Florencio, D’yaryo Bag Project of RCGM PP Boboy Campos, PP Emy Aguirre, 16 PP Benjie Liboro, PP Lito Bermundo, PP Rene Pineda Assistant Governor RY 2011-2012 GSE Inbound Team PP Dulo Chua, PP Ron Quan, PP Saldy 17 Quimpo, PP Mike Cinco, PP Ruben Aniceto, PP Arnold Divina, IPP Benj Ngo, District Awards Criteria PP Arnold Garcia, PP Nep Bulilan, 18 PP Ramir Tiamzon, PP Derek Santos PP Ver Cerafica, PP Edmed Medrano, PP Jun Martinez, PP Edwin Francisco, PP Cito Gesite, PP Tet Requiso, PP El The Majestic Team Breakfast Meeting Bello, PP Elmer Baltazar, PP Lorna 19 Bernardo, PP Joy Valenton, PP Paul January 2011 Castro, Jr., IPP Jun Salatandre, PP Freddie Miranda, PP Jimmy Ortigas, District 3800 PALAROTARY PP Akyat Sy, PP Vic Esparaz, PP Louie Diy, 20 PP Mike Santos, PP Jack Sia RC Pasig Sunrise PP Alfredo “Jun” T. -

Rockwell of Ages DESPITE Its Unassuming Moniker, the Garage in Rockwell Center Is a Hub of Activity, but Not of the Automotive Kind

MARCH 2013 www.lopezlink.ph See story on page 10 http://www.facebook.com/lopezlinkonline www.twitter.com/lopezlinkph Rockwell of ages DESPITE its unassuming moniker, the Garage in Rockwell Center is a hub of activity, but not of the automotive kind. Prospective sales executives in spiffy business attire wait to be called in for their appointments. Staff in uniform dress shorts and polo shirts flit around preparing the conference rooms and looking after guests. In the inner offices, twentysomethings type away at their computers. Even big boss Miguel L. Lopez, Rockwell Land Corporation senior vice Turn to page 6 Landslide Lea Salonga returns Power Plant Mall is ‘grad central’ …page 3 to TV …page 4 in Leyte …page 12 Lopezlink March 2013 BIZ NEWS NEWS Lopezlink March 2013 At the Pinoy Media Congress Landslide in Leyte FPH to redeem and Students urged to serve, ABS-CBN: GMA’S libel declare cash dividend love country; EL launches case has no basis EDC continues search on preferred shares ABS-CBN Corporation reiterat- THE board of directors of First shares starting on the fifth an- book of speeches ed its stand that the nine-year-old Philippine Holdings Corpora- niversary of the issue date. In his keynote address, EL3 libel case filed by GMA Network tion (FPH) has approved the Additionally, the board also against it has no basis. for missing workers company’s option to redeem approved payment of a cash ABS-CBN chairman Eugenio said the media’s role is to “serve ABS-CBN chairman Eu- A landslide possibly triggered while 10 were taken to the The workers were hired by families of the casualties and all of its 43,000,000 series B dividend on the series B preferred Lopez III (leftmost) with the people no matter what the genio Lopez III (EL3) and preferred shares. -

District 3800 Rotary Academy PP Marcelo “Jun” C

ROTARY INTERNATIONAL DISTRICT 3800 GOVERNOR’S MONTHLY OCTOBER 2011 LETTER DISTRICT GOVERNOR RAFAEL GARCIA iII and dgl minda with the majestic team at the oktober-fiesta OCTOBER 2011 CONTENTS ROTARY INTERNATIONAL District 3800 The Majestic Governor’s Message Rafael “Raffy” M. Garcia III 3 District Governor District Trainer PDG Jaime “James” O. Dee District Secretary District 3800 Rotary Academy PP Marcelo “Jun” C. Zafra 4 District Governor’s Aide PP Rodolfo “Rudy” L. Retirado Senior Deputy Governors PP Bobby Rosadia, PP Nelson Aspe, District 3800 October Fiesta PP Dan Santos, PP Luz Cotoco, PP Willy 8 Caballa, PP Tonipi Parungao, PP Joey Sy October 08, 2011 CP Marilou Co, CP Maricris Lim Pineda, CP Manny Reyes, PP Roland Garcia, PP Jerry Lim, PP Jun Angeles, PP Condrad Cuesta, CP Sunday Pineda. District 3800 RYLA 2011 Deputy District Secretary 10 PP Rudy Mendoza, PP Tommy Cua, October 21 -23, 2011 PP Danny Concepcion, PP Ching Umali, PP Alex Ang, PP Danny Valeriano, PP Augie Soliman, PP Pete Pinion PP John Barredo ART FROM THE HEART Deputy District Governor 12 CP Mila Puyat/ RC Greater Mandaluyong PP Roger Santiago, PP Lulu Sotto, PP Peter Quintana, PP Rene Florencio, PP Boboy Campos, PP Emy Aguirre, PP Benjie Liboro, PP Lito Bermundo, PP Rene Pineda District 3800 Duckpin Bowling Fellowship Assistant Governor PP Dulo Chua, PP Ron Quan, PP Saldy 13 MP Rod Macalinao/ RC Pasig North Quimpo, PP Mike Cinco, PP Ruben Aniceto, PP Arnold Divina, IPP Benj Ngo, PP Arnold Garcia, PP Nep Bulilan, PP Ramir Tiamzon, PP Derek Santos District Secretary’s Report PP Ver Cerafica, PP Edmed Medrano, 14 PP Jun Martinez, PP Edwin Francisco, DS Marcelo “Jun” Zafra, Jr PP Cito Gesite, PP Tet Requiso, PP El Bello, PP Elmer Baltazar, PP Lorna Bernardo, PP Joy Valenton, PP Paul Castro, Jr., IPP Jun Salatandre, District 3800 Attendance Report PP Freddie Miranda, PP Jimmy Ortigas, 15 PP Akyat Sy, PP Vic Esparaz, PP Louie Diy, August, 2011 PP Mike Santos, PP Jack Sia PP Alfredo “Jun” T. -

Economic Instruments for the Sustainable Management Of

Economic Instruments for the Sustainable Management of Natural Resources A Case Study on the Philippines’ Forestry Sector Economic Instruments for the Sustainable Management of Natural Resources A Case Study on the Philippines’ Forestry Sector National Institution leading the Study: University of the Philippines Los Baños, the Philippines National Team Contributing Authors: Herminia Francisco, Edwino Fernando, Celofe Torres, Eleno Peralta, Jose Sargento, Joselito Barile, Rex Victor Cruz, Leonida Bugayong, Priscila Dolom, Nena Espriritu, Margaret Calderon, Cerenilla Cruz, Roberto Cereno, Fe Mallion, Zenaida Sumalde, Wilfredo Carandang, Araceli Oliva, Jesus Castillo, Lolita Aquino, Lucrecio Rebugio, Josefina Dizon and Linda Peñalba UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 1999 NOTE The views and interpretation reflected in this document are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect an expression of opinion on the part on the United Nations Environment Programme. UNEP/99/4 ii The United Nations Environment Programme The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) is the overall coordinating environ- mental organisation of the United Nations system. Its mission is to provide leadership and encour- age partnerships in caring for the environment by inspiring, informing and enabling nations and people to improve their quality of life without compromising that of future generations. In accord- ance with its mandate, UNEP works to observe, monitor and assess the state of the global environ- ment, and improve our scientific understanding of how environmental change occurs, and in turn, how such changes can be managed by action-oriented national policies and international agree- ments. With today’s rapid pace of unprecedented environmental changes, UNEP works to build tools that help policy-makers better understand and respond to emerging environmental challenges. -

Extinguishment of Agency General Condition Revocation Withdrawal Of

Extinguishment of Agency General condition Revocation Withdrawal of agent Death of the Principal Death of the Agent CASES Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila FIRST DIVISION G.R. No. L-36585 July 16, 1984 MARIANO DIOLOSA and ALEGRIA VILLANUEVA-DIOLOSA, petitioners, vs. THE HON. COURT OF APPEALS, and QUIRINO BATERNA (As owner and proprietor of QUIN BATERNA REALTY), respondents. Enrique L. Soriano for petitioners. Domingo Laurea for private respondent. RELOVA, J.: Appeal by certiorari from a decision of the then Court of Appeals ordering herein petitioners to pay private respondent "the sum of P10,000.00 as damages and the sum of P2,000.00 as attorney's fees, and the costs." This case originated in the then Court of First Instance of Iloilo where private respondents instituted a case of recovery of unpaid commission against petitioners over some of the lots subject of an agency agreement that were not sold. Said complaint, docketed as Civil Case No. 7864 and entitled: "Quirino Baterna vs. Mariano Diolosa and Alegria Villanueva-Diolosa", was dismissed by the trial court after hearing. Thereafter, private respondent elevated the case to respondent court whose decision is the subject of the present petition. The parties — petitioners and respondents-agree on the findings of facts made by respondent court which are based largely on the pre-trial order of the trial court, as follows: PRE-TRIAL ORDER When this case was called for a pre-trial conference today, the plaintiff, assisted by Atty. Domingo Laurea, appeared and the defendants, assisted by Atty. Enrique Soriano, also appeared. A. -

REAL.ESTATE Cpdprogram.Pdf

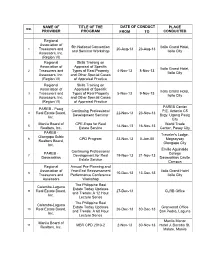

NAME OF TITLE OF THE DATE OF CONDUCT PLACE NO. PROVIDER PROGRAM FROM TO CONDUCTED Regional Association of 5th National Convention Iloilo Grand Hotel, 1 Treasurers and 20-Aug-13 23-Aug-13 and Seminar Workshop Iloilo City Assessors, Inc. (Region VI) Regional Skills Training on Association of Appraisal of Specific Iloilo Grand Hotel, 2 Treasurers and Types of Real Property 4-Nov-13 8-Nov-13 Iloilo City Assessors, Inc. and Other Special Cases (Region VI) of Appraisal Practice Regional Skills Training on Association of Appraisal of Specific Iloilo Grand Hotel, 3 Treasurers and Types of Real Property 5-Nov-13 9-Nov-13 Iloilo City Assessors, Inc. and Other Special Cases (Region VI) of Appraisal Practice PAREB Center PAREB - Pasig Continuing Professional P.E. Antonio C5 4 Real Estate Board, 22-Nov-13 23-Nov-13 Development Seminar Brgy. Ugong Pasig Inc. City Manila Board of CPE-Expo for Real World Trade 5 14-Nov-13 16-Nov-13 Realtors, Inc. Estate Service Center, Pasay City PAREB - Traveler's Lodge, Olongapo Subic 6 CPD Program 23-Nov-13 0-Jan-00 Magsaysay Realtors Board, Olongapo City Inc. Emilio Aguinaldo Continuing Professional PAREB - College 7 Development for Real 19-Nov-13 21-Nov-13 Dasmariñas Dasmariñas Cavite Estate Service Campus Regional Annual Pre-Planning and Association of Year-End Reassessment Iloilo Grand Hotel 8 10-Dec-13 13-Dec-13 Treasurers and Performance Conference Iloilo City Assessors Workshop The Philippine Real Calamba-Laguna Estate Today Updates 9 Real Estate Board, 27-Dec-13 CLRB Office and Trends: A 12 Hour Inc. -

SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS of the ) REPUBLIC of the PHILIPPINES ) •17 FEB-9 P2«4 First Regular Session )

^enati? 0( tiK .j-ftr rtflrp SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS OF THE ) REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES ) •17 FEB-9 P2«4 First Regular Session ) R E C E iV L O BY; S E N A T E S. B. No. Introduced by Senator Aquilino uKoko” Pimentel HI AN ACT DECLARING THE TWENTY THIRD DAY OF JANUARY OF EVERY YEAR AS A SPECIAL \\ ORKING HOLIDAY IN THE ENTIRE PHILIPPINES, TO COMMEMORATE THE DECLARATION OF THE FIRST PHILIPPINE REPUBLIC ON JANUARY 23, 1899 AT THE BARASOAIN CHURCH, MALOLOS, BULACAN, APPROPRIATING FUNDS THEREFOR, AND FOR OTHER PU RPOSES EXPLANATORY NOTE On January 23, 1899, the First Philippine Republic (also known as the ""Malolos Republic") was inaugurated at Barasoain Church, Malolos, Bulacan. This momentous event gave the Philippines the distinction of being the first independent Republic in Asia. In addition, the declaration ushered in the constitution of the central government of the new Republic, officially marking the claim of Filipinos to sovereignty after more than three centuries of Spanish colonial rule. The inauguration of the First Philippine Republic has been regarded as of equal significance with the Declaration of Independence on June 12, 1898 at Kawit, Cavite, and all other historic events leading towards the freedom of all Filipinos from foreign subjugation. In recognition of the importance of this date in Philippine history, former President Benigno S. Aquino III issued Proclamation No. 533 on January 9, 2013, declaring January 23 of every year as “/1/Y/vy ng Republikang Filipino, 1899." The foregoing measure seeks to declare January 23 of every year as a special working holiday to increase public awareness on the significance of the declaration of the First Philippine Republic, ensure meaningful observance of the same, and encourage people’s participation in the activities and programs that are to be spearheaded by the National Historical Commission. -

Preparatory Survey on Promotion of TOD for Urban Railway in the Republic of the Philippines Final Report Final Report

the Republic of Philippines Preparatory Survey on Promotion of TOD for Urban Railway in Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC) Philippine National Railways (PNR) Preparatory Survey on Promotion of TOD for Urban Railway in the Republic of the Philippines Final Report Final Report March 2015 March 2015 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) ALMEC Corporation Oriental Consultants Global Co., Ltd. 1R CR(3) 15-011 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MAIN TEXT 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Background and Rationale of the Study ....................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Objectives, Study Area and Counterpart Agencies ...................................................... 1-3 1.3 Study Implementation ................................................................................................... 1-4 2 CONCEPT OF TOD AND INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT ......................................... 2-1 2.1 Consept and Objectives of TOD ................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Approach to Implementation of TOD for NSCR ............................................................ 2-2 2.3 Good Practices of TOD ................................................................................................. 2-7 2.4 Regional Characteristics and Issues of the Project Area ............................................. 2-13 2.5 Corridor Characteristics and -

Metro Manila Market Update Q1 2017

RESEARCH METRO MANILA MARKET UPDATE Q1 2017 METRO MANILA REAL ESTATE SECTOR REVIEW METRO MANILA AND THE THREAT OF EMERGING CITIES The attractiveness of Metro Manila for real estate developers and investors continues to exist. Although highly congested and vacancy rates are constantly dwindling, it is still the best location for business and investment activities. Considering that the seat of government, head offices of key companies, and the most reputable universities and institutions are located in Metro Manila, demand is perceived to always be buoyant and pervasive. The real challenge is innovation and the creation of new stock to cater to the limitless demand. The Philippine National Economic and Development Authority defines Philippine Emerging Cities as cities, relative to Manila, that are rapidly catching up in terms of business activities, innovation and ability to attract people. A few of the notable emerging cities in the Philippines are Angeles (Clark), Cebu, Davao, Iloilo and Zamboanga. Cebu, Davao and Iloilo are top 5, 6 and 8, respectively, among the Philippine Highly Urbanized Cities (HUC) of the country. Angeles City’s makings is supplemented by the much- awaited Clark Green City. Zamboanga City was identified as one of the emerging cities when it comes to information technology Source: Wikipedia operations. The city has the propensity to flourish being the third major gateway and transshipment important transportation networks, largest city in the Philippines in hub in Northern Mindanao, it will increase access to jobs and terms of land area. Furthermore, continue to be a key educational services by people in smaller Bacolod, Bohol, Leyte, Naga, center in the region. -

In September 2011 While Researching at the National Archive of Vietnam in Hanoi, I Had the Good Fortune of Catching Bizet's Ca

CODA In September 2011 while researching at the National Archive of Vietnam in Hanoi, I had the good fortune of catching Bizet’s Carmen at the Hanoi Opera House [Nhà hát lớn Hà Nội] on the occasion of the theatre’s cen- tennial. The production featured Vietnamese soprano Vanh Khuyen as Carmen, tenors Thanh Binh and Nguyen Vu alternating as Don Jose, and Manh Dung as Escamillo. The production was accompanied by the Orchestra of Vietnam National Opera and Ballet conducted by British conductor Graham Sutcliffe. It was directed by Swedish director Helena Rohr, who had worked previously with the company through a cultural exchange between the Swedish and Vietnamese governments. Rohr’s staging of the opera was adapted to contemporary Hanoi setting: The tobacco factory was replaced with a Hanoi garment sweatshop. The opera house, built during the French occupation and finished in 1911, initially housed European opera and theatre companies performing for the European population until the end of the French rule. After the indepen- dence of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, the opera house served as an important political and government meeting house, occasionally hosting performing arts events. In 1995, the theatre was renovated and since then has been home to Vietnamese and Western classical concert music, opera, drama, and ballet. In 2012, while attending the Australasian Drama, Theatre, and Performance Studies Conference in Melbourne, I attended Prof. Barbara © The Author(s) 2018 225 m. yamomo, Theatre and Music in Manila and the Asia Pacific, 1869–1946, Transnational Theatre Histories, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-69176-3 226 CODA Hatley’s presentation of Il La Galigo, an opera conceived by Robert Wilson based on Rhoda Grauer’s adaptation of the Buginese scroll epic, Sureq Galigo of South Sulawesi.