Estonian As a “Man-Made” Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Johannes Aavik Ja Vene Kirjandus: Biograafiline Ja Kultuurilis- Ideoloogiline Kontekst 1 Tatjana Stepaništševa

Johannes Aavik ja vene kirjandus: biograafiline ja kultuurilis- ideoloogiline kontekst 1 Tatjana Stepaništševa Teesid: Johannes Aaviku ilukirjanduslikud tõlked täitsid tema jaoks eelkõige rahvuskeele uuen- damise rolli, seetõttu jäid originaali stiil ning autori väljendusvahendid tema enda keeleuuen- duste taustal tagaplaanile. Ent tõlgitavate teoste valik oli tingitud eluloolistest ning kultuurilis- ideelistest teguritest, mille rekonstrueerimine ongi siinse artikli uurimisobjektiks. Eesti ja vene kultuuri vahekorra spetsiifika 20. sajandi esimesel veerandil tingis Aaviku pöördumise nimelt vene kirjanduse retseptsiooni poole. Nagu artiklis näidatud, oli see komplitseeritud seostes tolleaegse kultuuri ja poliitilise olukorraga Eestis. DOI: 10.7592/methis.v20i25.16566 Märksõnad: Johannes Aavik, keeleuuendus, ilukirjanduse tõlge, eesti-vene kultuurikontaktid, Fjodor Dostojevski Käesolev artikkel jätkab 20. sajandi algul Eesti Vabariigis ilmunud vene kirjandus- klassika tõlgete uurimist, mille algus on avaldatud Johannes Aaviku tõlkeseeriat „Hirmu ja õuduse jutud“ (1914−1928) käsitlevas artiklis (Stepaništševa 2018). Eesti kultuuriloos on Aavik ennekõike tuntud kui keeleuuenduse eestvedaja, vähemal määral on uuritud tema ilukirjanduslikke tõlkeid. Eraldi uurimisobjektina ei ole varem käsitletud Aaviku ilukirjanduslikke tõlkeid vene keelest, kuigi neid ei ole vähe ning lisaks tõlkimisele oli Aavik tegev ka teiste tõlkijate tekstide toimetamisel. Aaviku materjalivalik oli spetsiifiline – tema põhieesmärgiks ei olnud mitte võõr- keelse (prantsuse, -

JOHANNES AAVIK, 120 Aastat Tagasi Sündinud Saaremaa Mees

JOHANNES AAVIK, 120 aastat tagasi sündinud Saaremaa mees Tiiu Erelt eesti keele instituudi vanemteadur Keel vajab uuendust, uuendus juhti XX sajandi alguses hakkas kuristik moodsa kultuuri nõuete ja maavillase eesti keele vahel eesti haritlastele üha selgemini kätte paistma. Esimesed, kes hakkasid nõudma keele radikaalset parandamist uue elu nõuete ko- haselt, olid kirjanikud. Ansomardi avaldas 1900. a Rahva Lõbulehes kirjutise „Eesti praeguse kirjakeele, kirjaviisi ja grammatika arvustus", kuid konkreetseid parandamiseeteid selles veel ei olnud. Parandamis- vajadusest kirjutas 1904. a Eesti Postimehe Lisas ka Maximilian Põdder, võrreldes keele parandamist taimede ja loomade parandamisega põllu- majanduses. Samal ajal astus esile uus põlvkond keelenõudlikke noori kirjanikke, kes 1905. aastaks ühinesid Noor-Eesti rühmituseks. Aeg oli küps, keeleuuendus vajas veel juhti ja selleks sai Johannes Aavik. Aavik oli läbinisti filoloog, aga mitte eesti filoloog (milleks tollal veel õppida ei saanud), vaid eelkõige romaani ja soome filoloog. Ta oli armunud keeltesse: gümnaasiumi ajal ladina keelesse, pärast prantsuse ja soome keelesse, olemata ükskõikne ka saksa, inglise ja vene keele vastu.1 Ta nautis eri keelte omapärasusi, väärtust ja ilu. Olles aastail 1900-1920 eriliselt meeldunud prantsuse keelde, kirjutas ta selles omaseks saanud keeles isegi osa oma keelelistest kirjutistest ja tõlkis need siis eesti keel- de. Romaani filoloogia õppimine Tartus, Nežinis ja Helsingis ning soome filoloogia Helsingis andsid kokku soliidse filoloogilise pagasi. Huvi eesti keele ja selle parandamise vastu sai alguse rahvuslikust meel- susest ja kirjanduslikest huvidest. Noorsoomlaste eeskujul tekkisid noor- 66 eestlased, kellede hulka Aavikki algusest peale kuulus. Teiste keelte tundmine sünnitas unistuse arendada eesti keel niisama rikkaks kui va- nad kultuurkeeled. Helsingis õppimise aastad vormisid seda unistust ning 1911. -

ESTONIAN LANGUAGE Kala on Puu Juures A Fish Is Near the Tree Literally: A Fish Is in the Root of a Tree

ESTONIAN LANGUAGE Kala on puu juures A fish is near the tree Literally: A fish is in the root of a tree ISBN 9985-9341-9-9 / Published by the Estonian Institute 2004 / Illustrations: Jaagup Roomet / Design: Aadam Kaarma LABOR Estonian Language Urmas Sutrop Estonian is used in the army... aviation... theatre The Estonian language The ancestors of the Estonians arrived at Finnish, Hungarian and Estonian are the the Baltic Sea 13 000 years ago when the best known of the Finno-Ugric languages; mainland glaciers of the last Ice Age had rather less known are the following retreated from the area now designated smaller languages of the same language as Estonia. The first settlers who followed group: South Estonian, Votian, Livonian, the reindeer herds came here from south, Izhorian, Vepsian, Karelian, Sami, Erzya, from Central Europe. Although the vocab- Moksha, Mari, Udmurt and Komi, spoken ulary and grammar of the language used from Scandinavia to Siberia. by people in those days have changed beyond recognition, the mentality of the Estonian differs from its closest large tundra hunters of thousands of years ago related language, Finnish, at least as can be still perceived in modern Estonian. much as English differs from Frisian. The difference between Estonian and Hungar- The majority of European languages ian is about as significant as between belong to the Indo-European language German and Persian. group (e.g. Spanish, Polish, Lithuanian, Norwegian, Albanian, Romany, Greek or Along with Icelandic, Estonian is at Welsh). Of the ancient European langua- present one of the smallest languages in ges, once so widespread throughout the the world that fulfils all the functions continent, Basque in the Pyrenees, the necessary for an independent state to Finno-Ugric languages in the North and perform linguistically. -

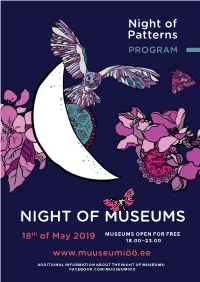

NIGHT of MUSEUMS 18TH of MAY TALLINN Night of Patterns PROGRAM

NIGHT OF MUSEUMS 18TH OF MAY TALLINN Night of Patterns PROGRAM NIGHT OF MUSEUMS th MUSEUMS OPEN FOR FREE 18 of May 2019 18.0023.00 www.muuseumiöö.ee ADDITIONAL INFORMATION ABOUT THE NIGHT OF MUSEUMS: FACEBOOK.COM/MUUSEUMIOO NIGHT OF MUSEUMS 18TH OF MAY SAARE COUNTY RUHNU MUSEUM Performances by female groups “Tokkroes” (from Muhu) and “Pääsukesed” (from Tallinn). RUHNU, RUHNU VALD. OPENING HOURS FOR THE MUSEUM NIGHT: 18–23. Several exhibitions will be opened. Children can The museum and its nearly two-centuries- take part in crafting, drawing and colouring of old Korsi farmhouse, unique in Estonia for its patterns in the old Koguva schoolhouse. The foundationless longhouse and humped roof, are museum shop is open for visitors. open for the Museum Night. SAAREMAA MUSEUM – THE SAAREMAA MUSEUM – AAVIK FAMILY HOUSE MUSEUM KURESSAARE EPISCOPAL VALLIMAA 7, KURESSAARE. OPENING CASTLE HOURS FOR THE MUSEUM NIGHT: 18–22. LOSSIHOOV 1, KURESSAARE LINN. OPENING The museum features a permanent exhibition HOURS FOR THE MUSEUM NIGHT: 18–23. (in Estonian and English) on the life and work of Estonian language moderniser Johannes Aavik 18.00 Musical welcome by a brass band in front and his cousin, cultural figure Joosep Aavik. of the castle In addition, the interior of the museum gives 18.05 The Museum Night is declared open with a good glimpse of the urban life of early 20th- the castle cannon “Kotkas” (“Eagle”) century Kuressaare. 18.15 Group hug (in folk costumes) for the castle SAAREMAA MUSEUM – MIHKLI 18.15 The hug is accompanied by music from the brass band FARM MUSEUM VIKI VILLAGE, KIHELKONNA BOROUGH. -

Introduction 1 Decadence in Nordic Literature

Part I Introduction 1 Decadence in Nordic Literature An Overview Pirjo Lyytikäinen, Riikka Rossi, Viola Parente-Čapková, and Mirjam Hinrikus Decadence, “a strange and singular plant” growing “in the over-cultivated soil of modern society”? (Hansson 2002, 4).1 This is how Swedish author Ola Hansson interpreted the title of his Sensitiva amorosa (1887), one of the landmarks of Nordic decadence. Hansson signaled his decadent stance by introducing the Baudelairean trope of “sick” or “evil” flowers in his text studying “unnatural” erotics. The strange poisonous herb invented by the author, as further explained in the poetic preface to the prose-poem-like stories, was a plant with morbid veins and “sickly sweet scent,” and with a color resembling “the light in a sickroom.”2 As a metaphor, the trope characterized Hansson’s work, reminding us of an essay by J.-K. Huysmans, where he describes decadent texts that grow from the soil of the dreams of exceptional individuals as a reaction to the disgusting materialistic tyranny of money.3 These blossoms of the genius of the decadent age were supposed to manifest the creative spirit of the new art that sought to go against the grain while revealing it as the outgrowth of the muddy soil of a decaying culture. In the Nordic countries, these herbs were not welcomed by those who guarded the national cultures, as Hansson himself was to experience. Still, a great variety of these outgrowths or decadent texts emerged from the Nordic soil. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the spread of European currents in Nordic countries caused unusually strong tensions in the local cultures. -

Traditional and Contemporary Issues in the Use and Learning of Finno-Ugric Languages

Traditional and contemporary issues in the use and learning of Finno-Ugric languages Tis 28th issue of Lähivõrdlusi. Lähivertailuja is partly based on papers presented at the 20th anniversary conference of the VIRSU network in Tallinn on October 5th and 6th, 2017. Te languages under study in most of the articles are Estonian and Finnish, but two further Finno- Ugric languages, namely Karelian and Hungarian, are also dealt with in some contributions. A central theme present in many contributions is the history of linguistics and language teaching and the impact of tradi- tions on today’s linguistics. Mati Hint deals with issues of quantity in Estonian phonology, start- ing with the Estonian grammars of Eduard Ahrens (1843, 2nd edition 1853), which established the current Estonian orthography and, in gen- eral, initiated the so-called Finnish turn in Estonian linguistics. Hint compares the sound systems and morphophonology in Estonian and Finnish and presents a detailed treatment of the impact of Ahrens on subsequent descriptions of the Estonian quantity system. In particular, he analyses and criticizes the theory of three phonemic quantity grades, frst presented by Mihkel Veske, and its more recent adaptations. Päivi Laine and Eve Mikone write about the terminology of geogra- phy in Estonia and Finland, focusing on the historical role of the Finn- ish geographer J. G. Granö. During his academic career, Granö worked both in Finland and in Estonia and contributed to the development of terminology in both Finnish and Estonian. His achievements illustrate the long traditions and mutual infuences in the scientifc cooperation between Finland and Estonia, in particular, between the universities of Tartu and Turku. -

Programme of the 24 International Baltic Conference of History of Science at Tallinn School of Economics and Business Administra

Programme of the 24th International Baltic Conference of History of Science at Tallinn School of Economics and Business Administration, Tallinn University of Technology October the 8th 2010 Registration 10.00 -11.00 at Akadeemia tee 3 PLENARY SESSION (11.00-12.30, room X-209): Moderator: Peeter Müürsepp Opening words by the Rector of Tallinn University of Technology Prof Andres Keevallik Opening address by the Chairman of the Organizing Committee Prof Peeter Müürsepp Juozas Algimantas Krikštopaitis (Lithuanian Research Institute of Culture; Lithuanian Association of the History and Philosophy of Science). Is it worthwhile choosing a joint Baltic course of intellectual action? Eero Loone (Tallinn University of Technology / University of Tartu, Estonia). Functions of History of Science for Philosophy of Science Jānis Stradiņš (Latvian Academy of Sciences, Riga, Latvia). Twenty years of the Association of the History and Philosophy of Science of the Baltic States LUNCH 12.30-14.00 PARALLEL SESSIONS (14.00-16.00 and 16.30-18.30) SECTION I: PHILOSOPHY AND METHODOLOGY OF SCIENCE (14.00-16.00, room X-310) Moderator: Rein Vihalemm Keyvan Alasti (Iranian Institute of Philosophy, Tehran, Iran). Incommensurability and Causal Theory of Reference: Phlogiston Case Enn Kasak (University of Tartu, Estonia). Unperceived Civil Religion in Science Endla Lõhkivi (Institute of Philosophy and Semiotics, University of Tartu, Estonia). Does identity matter? Reflections on the rationality and culture of science Peeter Müürsepp (Tallinn University of Technology, Estonia). Knowledge in Science and Non-Science Leo Näpinen (Tallinn University of Technology, Tallinn, Estonia). On the Unfitness of the Exact Sciences for the Understanding of Nature Birute Railiene (The Wroblewsky Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences, Vilnius, Lithuania). -

Estonian Language Estonian Institute Suur-Karja 14, Tallinn 10140, Estonia Tel

Estonian Language Estonian Institute Suur-Karja 14, Tallinn 10140, Estonia Tel. +372 631 4355, e-mail: [email protected] estinst.ee ISBN 978-9949-558-06-3 (trükis) ISBN 978-9949-558-07-0 (pdf) Published by the Estonian Institute in 2015, 5th edition. Illustrations: Jaagup Roomet Graphic design by AKSK, aksk.ee Estonian Language Urmas Sutrop Estonian is used in the army… aviation… theatre 2 3 The Estonian language The ancestors of the Estonians arrived at the Baltic Sea 11 000 years ago when the mainland glaciers of the last Ice Age had retreated from the area now des- ignated as Estonia. The first settlers who followed the reindeer herds came here from south, from Central Europe. Although the vocabulary and grammar of the language used by people in those days have changed beyond recognition, the mentality of the tundra hunters of thousands of years ago can be still perceived in modern Estonian. The majority of European languages belong to the Indo-European language group (e.g. Spanish, Polish, Lithuanian, Norwegian, Albanian, Romany, Greek or Welsh). Of the ancient European languages, once so widespread throughout the continent, Basque in the Pyrenees, the Finno-Ugric languages in the North and Central Europe, and Caucasian languages (e.g. Georgian) in the southeastern corner of Europe have managed to survive. The Estonian language belongs to the Finnic branch of Finno-Ugric group of lan- guages. It is not therefore related to the neighbouring Indo-European languages such as Russian, Latvian and Swedish. Finnish, Hungarian and Estonian are the best known of the Finno-Ugric languages; rather less known are the following smaller languages of the same language group: South Estonian, Votic, Livonian, Ingrian, Veps, Karelian, Ludic, Sami, Erzya, Moksha, Mari, Udmurt, Komi, Mansi and Khanty spoken from Scandinavia to Siberia. -

Hilise Aaviku Radikaalne Keeleuuendus

Mati Hint, avaartikkel_Layout 1 31.01.12 12:12 Page 81 Keel ja 2/2012 Kirjandus LV AASTAKäIK EESTI TEAduSTE AKAdEEmIA JA EESTI KIrJANIKE LIIdu AJAKIrI HILISE AAVIKU RADIKAALNE KEELEUUENDUS mATI HINT „Ideepe” 1 ohannes Aaviku sõjaaegne isiklik päevik (31. jaanuarist 1942 kuni 1. det - sembrini 1943), mis üllitati tema 130. sünniaastapäevaks (8. XII 2010), Jmuudab kindlasti järelpõlve pilti Aaviku isiksusest ning tema keeleuuen - dusest. „Ideepe” (< idee + päevik) pidi Aaviku kavatsuse järgi esitama „kogu Keeleuuenduse filosoofia ja ideoloogi a....” (69 72). Koos Aaviku isiksuse detail - vaadetega näitab päevaraamat ka radikaalset keeleuuendust uudses raken - duslikus valguses, sest päeviku keel on keeleuuenduslik. Keeleuuendusest on eesti avalikkuses kõneldud-kirjutatud palju üldsõna - list pateetikat. radikaalse lõpmatuseni ulatuva keeleuuenduse hukatuslik - kust pole teoreetiliselt kuigi põhjalikult analüüsitud (Valter Tauli ütleb siis - ki mõndagi, kuid tal polnud lugeda „Ideepet”, vt Tauli 1982a; 1982b). „Ideepe” kirjutamise ajal üle 60-aastase Aaviku keeleuuendus on ta varasematest pro - grammidest veelgi ründavam, seetõttu on selle teoreetiline analüüs vajalik. „Ideepe” käsitlus on jagatud kolme ossa: 1. Hilise Aaviku radikaalne keeleuuendus. 2. Aaviku isiksus „Ideepes”. 3. Aaviku esteetilised vaated. Kaks viimast alajaotust ilmuvad loodetavasti Loomingus. Need käsitlevad Aaviku 1 „Ideepe.” Johannes Aaviku ideede päevik. Väljaande koostaja ja peatoimetaja Helgi Vihma. Keele- ja tehniline toimetaja, registrite koostaja Aili Norberg. -

The Hungarian Language Reform in European Comparison.” Hungarian Cultural Studies

Laakso, Johanna. “Hungarian Is No Idioma Incomparabile: The Hungarian Language Reform in European Comparison.” Hungarian Cultural Studies. e-Journal of the American Hungarian Educators Association, Volume 7 (2014): http://ahea.pitt.edu DOI: 10.5195/ahea.2014.165 Hungarian Is No Idioma Incomparabile: The Hungarian Language 1 Reform in European Comparison Johanna Laakso Abstract: The idea of the uniqueness of the Hungarian language is firmly rooted in Hungarian culture and discourse. Accordingly, the language reform (“nyelvújítás”)—the movement which led to the standardization of Modern Hungarian orthography and grammar and a radical renewal of the lexicon, especially by way of numerous neologisms, in the nineteenth century—is often seen as part of specifically Hungarian cultural history rather than in the framework of European ideologies. This paper briefly presents the most relevant linguistic aspects of the language reform and analyzes its connections to contemporary linguistic culture, the ideologies of late Enlightenment and Romantic Nationalism, and the progress in linguistics. Keywords: Hungarian Language, Language Planning, Lexicon, Derivation, Nationalism, Emancipation Biography: Johanna Laakso studied Finno-Ugric and Finnic languages and general linguistics at the University of Helsinki, where she acquired her PhD in 1990. In 2000, she was appointed to the post of Professor in Finno-Ugric Studies at the University of Vienna. Her research interests include historical linguistics (in particular, historical morphology and word-formation) and gender linguistics, as well as issues of language contact and multilingualism. In 2010–2013, she was occupied with the international research project ELDIA (European Language Diversity for All) on the multilingualism of modern minorities, in which she led the case study on the Hungarians in Austria. -

Planning and Purism

Planning and purism: ideological forces in shaping linguistic identity Autor(es): Vihman, VirveAnneli Publicado por: Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra URL persistente: URI:http://hdl.handle.net/10316.2/43209 DOI: DOI:https://doi.org/10.14195/978-989-26-1483-0_2 Accessed : 26-Sep-2021 14:04:54 A navegação consulta e descarregamento dos títulos inseridos nas Bibliotecas Digitais UC Digitalis, UC Pombalina e UC Impactum, pressupõem a aceitação plena e sem reservas dos Termos e Condições de Uso destas Bibliotecas Digitais, disponíveis em https://digitalis.uc.pt/pt-pt/termos. Conforme exposto nos referidos Termos e Condições de Uso, o descarregamento de títulos de acesso restrito requer uma licença válida de autorização devendo o utilizador aceder ao(s) documento(s) a partir de um endereço de IP da instituição detentora da supramencionada licença. Ao utilizador é apenas permitido o descarregamento para uso pessoal, pelo que o emprego do(s) título(s) descarregado(s) para outro fim, designadamente comercial, carece de autorização do respetivo autor ou editor da obra. Na medida em que todas as obras da UC Digitalis se encontram protegidas pelo Código do Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos e demais legislação aplicável, toda a cópia, parcial ou total, deste documento, nos casos em que é legalmente admitida, deverá conter ou fazer-se acompanhar por este aviso. pombalina.uc.pt digitalis.uc.pt ANA PAULA ARNAUT ANA PAULA IDENTITY(IES) A MULTICULTURAL AND (ORG.) MULTIDISCIPLINARY APPROACH ANA PAULA ARNAUT IDENTITY(IES) (ORG.) IMPRENSA DA UNIVERSIDADE DE COIMBRA COIMBRA UNIVERSITY PRESS P LA nning A nd P U ri SM : I deo L ogi CAL F or C E S in S HA ping L ing U I ST I C I den T I TY 3 1 Virve ‑Anneli Vihman, University of Tartu Abstract: National identity is typically conservative, reflecting a collective understanding and carried by symbols and signs that have had time to take root. -

Notes on Contributors

Notes on Contributors Claude Debru obtained his Ph.D. in Philosophy from the University of Lyon (France) in 1982. He is professor of philosophy of science and head of the Philosophy Department of the Ēcole Normale Supérieure Paris, where he teaches philosophy and epistemology to students in science as well as in the humanities. He is presently interested in the (scientific and philosophical) problem of the sources of human normativity. Anita Draveniece holds a Ph.D. in Geography from the University of Latvia (2006). She is working for the international research collaboration at the Latvian Academy of Sciences, and since 2005 she was adviser to the Academy president and head of the international relations group. Over the past six years she has been involved in analysis and reporting on issues dealing with R&D system and policy in Latvia. Anastasia A. Fedotova is researcher at the St Petersburg Branch of Institute for the History of Science and Technology, RAS. Her research interests are the history of botany, environmental history and the role of scientific knowledge in the rationalization of agriculture and forestry in Russia (19th to early 20th cc). She is a member of editorial office of the journalStudies in the History of Biology. Kateryna N. Gamaliya obtained her Candidate’s degree in History, specializing in the History of Science and Technology, in 2007 from the Dobrov Centre for Scientific and Technological Potential and Science History Studies of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. She is head of the Department of the History of Art and Ethnic Culture of the Salvador Dali Art Institution of Art Modelling and Design.