Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USER MANUAL Artiste: M.S

248. Anu Dinamunu Artistes: M.S. Subbulakshmi & Radha Vishwanathan Composer: Ramanathapuram Srinivasa Iyengar 249. Naraveshabhushana Artiste: M.S. Subbulakshmi Lyricist: Traditional Music Director: Kadayanallur S. Venkataraman 250. Manju Nihar Artistes: M.S. Subbulakshmi & Radha Vishwanathan Composer: Annamalai Reddiar 251. Muzhudai Unarndavar USER MANUAL Artiste: M.S. Subbulakshmi Composer: Athma visit www.saregama.com/carvaanmini to download the entire songlist 44 239. Sirai Aarum Artistes: M.S. Subbulakshmi & Radha Vishwanathan Composer: Thirugnana Sambandar 240. Sada Saranga Nayane Artiste: M.S. Subbulakshmi Composer: Mysore H. Yoganarasimham 241. Vanajaakshi 1. Overview - Buttons and Ports 3 Artiste: M.S. Subbulakshmi Composer: Traditional 242. Tum Ho Jag Ke 2. Modes 5 Artiste: M.S. Subbulakshmi Lyricist: Ustad Mohd. Dilshad Khan Music Director: Kadayanallur S. Venkataraman 3. Playback Status Light 8 243. Ko Va Rago Vadito Artiste: M.S. Subbulakshmi Lyricist: Mysore H Yoganarasimham 4. Battery 8 Music Director: Gurunanak Shabad, P.S.Srinivasa Rao 244. Mere To Giridhar Artistes: M.S. Subbulakshmi & Gowri Ramanarayanan 5. Safety Handling 8 Composer: Meera 245. Varuga Varugave 6. Warranty Overview 10 Artistes: M.S. Subbulakshmi & Radha Vishwanathan Composer: Ambujam Krishna 246. Sai Charan Ma 7. Song List 18 Artiste: M.S. Subbulakshmi Lyricist: Suresh Dalal Music Director: Ashit Desai 247. Dinudanenu Devuduvu Nivu Artistes: M.S. Subbulakshmi & Radha Vishwanathan Composer: Annamacharya 2 43 231. Oru Thram Saravana Bhava Artiste: M.S. Subbulakshmi Overview - Buttons and Ports Lyricist: Traditional Music Director: Kadayanallur S. Venkataraman 232. Maanilathai Vaazha Vaika Artiste: M.S. Subbulakshmi Lyricist: Kalki R.Krishnamurthy Music Director: Kadayanallur S. Venkataraman 233. Nee Saati Daivamu Artistes: M.S. Subbulakshmi & Radha Vishwanathan Previous Composer: Muthuswami Dikshitar 234. -

(Hons.) Karnatak Music (Vocal/ Instrumental) Submitted to University Grants Commission New Delhi Under Choice Based Credit System

Syllabus of B.A. (Hons.) Karnatak Music (Vocal/ Instrumental) Submitted to University Grants Commission New Delhi Under Choice Based Credit System CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM 2015 DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC FACULTY OF MUSIC & FINE ARTS UNIVERSITY OF DELHI DELHI-110007 1 CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM IN B.A HONOURS KARNATAK MUSIC (VOCAL/INSTRUMENTAL) Semester CORE COURSE (14) Ability Skill Elective: Discipline Elective: Enhancement Enhancement Specific DSE (4) Generic (GE) Compulsory Course (SEC) (2) (4) Course(AECC) (2) I C 1 Theory: General (English/MIL GE-1 Musicology Communication)/ C 2 Practical : Stage Environmental Performance & Science Viva-Voce II C 3Theory: Environmental GE-2 Theory of Indian Music Science/(English/MI C 4 Practical : Stage L Communication) Performance & Viva-Voce III C 5 Theory: SEC-1 GE-3 Indian Musicology C 6 Practical : Stage Performance C 7 Practical : Viva Voce IV C 8 Theory : Indian SEC-2 GE-4 Music C 9 Practical : Stage Performance C 10 Practical : Viva Voce V C 11 Theory: *DSE-1 Indian Music Vocal/Instrumental C 12 Practical : Stage /Karnatak/Percussi Performance & Viva on Music: Voce (Tabla/Pakhawaj) *DSE-2 Vocal/Instrumental /Karnatak/Percussi on Music: (Tabla/Pakhawaj) VI C 13 Theory : Study of *DSE-3 Hindustani Music Vocal/Instrumental C 14 Practical : Stage /Karnatak/Percussi Performance & Viva on Music: Voce (Tabla/Pakhawaj) *DSE -4 Project Work: Vocal/Instrumental /Karnatak/Percussi on Music 2 *These courses shall be offered to the students of B.A. Honours, other than their own discipline. Syllabus for B.A. -

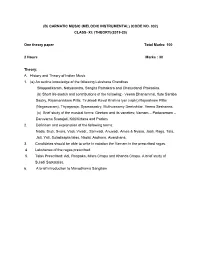

Carnatic Music (Melodic Instrumental) (Code No

(B) CARNATIC MUSIC (MELODIC INSTRUMENTAL) (CODE NO. 032) CLASS–XI: (THEORY)(2019-20) One theory paper Total Marks: 100 2 Hours Marks : 30 Theory: A. History and Theory of Indian Music 1. (a) An outline knowledge of the following Lakshana Grandhas Silappadikaram, Natyasastra, Sangita Ratnakara and Chaturdandi Prakasika. (b) Short life sketch and contributions of the following:- Veena Dhanammal, flute Saraba Sastry, Rajamanikkam Pillai, Tirukkodi Kaval Krishna lyer (violin) Rajaratnam Pillai (Nagasvaram), Thyagaraja, Syamasastry, Muthuswamy Deekshitar, Veena Seshanna. (c) Brief study of the musical forms: Geetam and its varieties; Varnam – Padavarnam – Daruvarna Svarajati, Kriti/Kirtana and Padam 2. Definition and explanation of the following terms: Nada, Sruti, Svara, Vadi, Vivadi:, Samvadi, Anuvadi, Amsa & Nyasa, Jaati, Raga, Tala, Jati, Yati, Suladisapta talas, Nadai, Arohana, Avarohana. 3. Candidates should be able to write in notation the Varnam in the prescribed ragas. 4. Lakshanas of the ragas prescribed. 5. Talas Prescribed: Adi, Roopaka, Misra Chapu and Khanda Chapu. A brief study of Suladi Saptatalas. 6. A brief introduction to Manodhama Sangitam CLASS–XI (PRACTICAL) One Practical Paper Marks: 70 B. Practical Activities 1. Ragas Prescribed: Mayamalavagowla, Sankarabharana, Kharaharapriya, Kalyani, Kambhoji, Madhyamavati, Arabhi, Pantuvarali Kedaragaula, Vasanta, Anandabharavi, Kanada, Dhanyasi. 2. Varnams (atleast three) in Aditala in two degree of speed. 3. Kriti/Kirtana in each of the prescribed ragas, covering the main Talas Adi, Rupakam and Chapu. 4. Brief alapana of the ragas prescribed. 5. Technique of playing niraval and kalpana svaras in Adi, and Rupaka talas in two degrees of speed. 6. The candidate should be able to produce all the gamakas pertaining to the chosen instrument. -

Senior School Curriculum 2017-18

SENIOR SCHOOL CURRICULUM 2017-18 VOLUME - III Music and Dance for Class XII Central Board of Secondary Education “Shiksha Sadan”, 17, Rouse Avenue, New Delhi – 110 002 / Telephone : +91-11-23237780 /Website : www.cbseacademic.in Downloaded from: www.cbseportal.com Courtesy : CBSE Senior School Curriculum 2017 - 18 Volume - III CBSE, Delhi – 110092 March, 2017 Copies: Price: ` This book or part thereof may not be reproduced by any person or Agency in any manner Published by: The Secretary, CBSE Printed by: Multi Graphics, 8A/101, WEA Karol Bagh, New Delhi – 110 005, Phone: 25783846 Printed by: II Downloaded from: www.cbseportal.com Courtesy : CBSE CONTENTS Page No. Music and Dance Syllabus (i) Carnatic Music 1 (a) Carnatic Music (Vocal) 2 (b) Carnatic Music (Melodic Instrument) 6 (c) Carnatic Music (Percussion Instrumental) 10 (ii) Hindustani Music 15 (a) Hindustani Music (Vocal) 16 (b) Hindustani Music (Melodic Instrument) 19 (c) Hindustani Music (Percussion Instrumental) 22 (iii) (a) Dances 25 (a) Kathak 27 (b) Bharatnatyam 32 (c) Kuchipudi 36 (d) Odissi 38 (e) Manipuri 42 (f) Kathakali 46 (g) Mohiniyattam 49 III Downloaded from: www.cbseportal.com Courtesy : CBSE SENIOR SCHOOL CURRICULUM 2017-18 VOLUME III (i) Carnatic Music Effective from the academic session 2017–2018 for Classes–XI and XII 1 Downloaded from: www.cbseportal.com Courtesy : CBSE (A) CARNATIC MUSIC (VOCAL): (CODE NO. 031) CLASS–XII (2017-18): (THEORY) One Theory Paper Total Marks: 100 3 Hours Marks: 30 72 Periods Theory: A. History and Theory of Indian Music 1. (a) Brief history of Carnatic music with special reference to Sangita Saramrita, Sangita Sampradaya Pradarsini, Svaramelakalanidhi, Raga Vibodham, Brihaddesi. -

Srirangam – Heaven on Earth

Srirangam – Heaven on Earth A Guide to Heaven – The past and present of Srirangam Pradeep Chakravarthy 3/1/2010 For the Tag Heritage Lecture Series 1 ARCHIVAL PICTURES IN THE PRESENTATION © COLLEGE OF ARTS, OTHER IMAGES © THE AUTHOR 2 Narada! How can I speak of the greatness of Srirangam? Fourteen divine years are not enough for me to say and for you to listen Yama’s predicament is worse than mine! He has no kingdom to rule over! All mortals go to Srirangam and have their sins expiated And the devas? They too go to Srirangam to be born as mortals! Shiva to Narada in the Sriranga Mahatmaya Introduction Great civilizations have been created and sustained around river systems across the world. India is no exception and in the Tamil country amongst the most famous rivers, Kaveri (among the seven sacred rivers of India) has been the source of wealth for several dynasties that rose and fell along her banks. Affectionately called Ponni, alluding to Pon being gold, the Kaveri river flows in Tamil Nadu for approx. 445 Kilometers out of its 765 Kilometers. Ancient poets have extolled her beauty and compared her to a woman who wears many fine jewels. If these jewels are the prosperous settlements on her banks, the island of Srirangam 500 acres and 13 kilometers long and 7 kilometers at its widest must be her crest jewel. Everything about Srirangam is massive – it is at 156 acres (perimeter of 10,710 feet) the largest Hindu temple complex in worship after Angkor which is now a Buddhist temple. -

The Journal of the Music Academy Madras Devoted to the Advancement of the Science and Art of Music

The Journal of Music Academy Madras ISSN. 0970-3101 Publication by THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS Sangita Sampradaya Pradarsini of Subbarama Dikshitar (Tamil) Part I, II & III each 150.00 Part – IV 50.00 Part – V 180.00 The Journal Sangita Sampradaya Pradarsini of Subbarama Dikshitar of (English) Volume – I 750.00 Volume – II 900.00 The Music Academy Madras Volume – III 900.00 Devoted to the Advancement of the Science and Art of Music Volume – IV 650.00 Volume – V 750.00 Vol. 89 2018 Appendix (A & B) Veena Seshannavin Uruppadigal (in Tamil) 250.00 ŸÊ„¢U fl‚ÊÁ◊ flÒ∑ȧá∆U Ÿ ÿÊÁªNÔUŒÿ ⁄UflÊÒ– Ragas of Sangita Saramrta – T.V. Subba Rao & ◊jQÊ— ÿòÊ ªÊÿÁãà ÃòÊ ÁÃDÊÁ◊ ŸÊ⁄UŒH Dr. S.R. Janakiraman (in English) 50.00 “I dwell not in Vaikunta, nor in the hearts of Yogins, not in the Sun; Lakshana Gitas – Dr. S.R. Janakiraman 50.00 (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada !” Narada Bhakti Sutra The Chaturdandi Prakasika of Venkatamakhin 50.00 (Sanskrit Text with supplement) E Krishna Iyer Centenary Issue 25.00 Professor Sambamoorthy, the Visionary Musicologist 150.00 By Brahma EDITOR Sriram V. Raga Lakshanangal – Dr. S.R. Janakiraman (in Tamil) Volume – I, II & III each 150.00 VOL. 89 – 2018 VOL. COMPUPRINT • 2811 6768 Published by N. Murali on behalf The Music Academy Madras at New No. 168, TTK Road, Royapettah, Chennai 600 014 and Printed by N. Subramanian at Sudarsan Graphics Offset Press, 14, Neelakanta Metha Street, T. Nagar, Chennai 600 014. Editor : V. Sriram. THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS ISSN. -

Ramanuja Darshanam

Table of Contents Ramanuja Darshanam Editor: Editorial 1 Sri Sridhar Srinivasan Who is the quintessential SriVaishnava Sri Kuresha - The embodiment of all 3 Associate Editor: RAMANUJA DARSHANAM Sri Vaishnava virtues Smt Harini Raghavan Kulashekhara Azhvar & 8 (Philosophy of Ramanuja) Perumal Thirumozhi Anubhavam Advisory Board: Great Saints and Teachers 18 Sri Mukundan Pattangi Sri Stavam of KooratazhvAn 24 Sri TA Varadhan Divine Places – Thirumal irum Solai 26 Sri TCA Venkatesan Gadya Trayam of Swami Ramanuja 30 Subscription: Moral story 34 Each Issue: $5 Website in focus 36 Annual: $20 Answers to Last Quiz 36 Calendar (Jan – Mar 04) 37 Email [email protected] About the Cover image The cover of this issue presents the image of Swami Ramanuja, as seen in the temple of Lord Srinivasa at Thirumala (Thirupathi). This image is very unique. Here, one can see Ramanuja with the gnyAna mudra (the sign of a teacher; see his right/left hands); usually, Swami Ramanuja’s images always present him in the anjali mudra (offering worship, both hands together in obeisance). Our elders say that Swami Ramanuja’s image at Thirumala shows the gnyAna mudra, because it is here that Swami Ramanuja gave his lectures on Vedarta Sangraha, his insightful, profound treatise on the meaning of the Upanishads. It is also said that Swami Ramanuja here is considered an Acharya to Lord Srinivasa Himself, and that is why the hundi is located right in front of swami Ramanuja at the temple (as a mark of respect to an Acharya). In Thirumala, other than Lord Srinivasa, Varaha, Narasimha and A VEDICS JOURNAL Varadaraja, the only other accepted shrine is that of Swami Ramanuja. -

A Rhythm of His Own V

COVER STORY KARAIKUDI MANI A rhythm of his own V. Karpagalakshmi Ramanatha Iyer, who had learnt music from Mazhavarayanendal Subbarama Bhagavatar as well as Swaminatha Iyer of Ganapati Agraharam, was a keen music enthusiast, well-versed in the bhajanai paddhati. Their home in Karaikudi was right opposite Ariyakudi Ramanuja Iyengar’s. In fact, Iyengar’s disciples K.V. Narayanaswamy and B. Rajam Iyer regularly partook of the simple breakfast of pazhaiyadu or rice soaked overnight in water and buttermilk, at Ramanatha Iyer’s household. The Nagarathars of Chettinad often sponsored concerts by the leading vidwans at Karaikudi; Ramanatha Iyer not only did not miss a single concert but also cultivated the friendship of the musicians and invited them home. It was but natural for Mani to be initiated into Carnatic music by his father, that too as early as at the age of three. By the time he was four, Mani had learnt all five of Tyagaraja’s Pancharatna kritis. In the month of Margazhi, father and son regularly woke up at the crack of dawn to join the bhajanai at the Koppudai Amman temple. During temple festivals, Ramanatha Iyer carried young Mani aloft on his shoulders to watch nagaswara vidwans Karukurichi Arunachalam and Vedaranyam Vedamurthy and tavil artist Nachiarkoil Raghava Pillai lead the procession around the four mada veedis – the streets around the temple. It was ridangam maestro Mani was born on during these processions, which began at nine at night and 11 September 1945 in Karaikudi, Tamil Nadu. often went on into the early hours of the morning after, MHis father T. -

Abhinaya in Bharatanatyam

PAPER 6 DANCE IN INDIA TODAY, DANCE-DRAMAS, CREATIVITY WITHIN THE CLASSICAL FORMS, INDIAN CLASSICAL DANCE IN DIASPORA (USA, UK, EUROPE, AUSTRALIA, ETC.) MODULE 19 THE EARLY FEMALE GURUS AND DANCERS OF BHARATANATYAM From early 1900 A D, some brave girls and their families started a journey, going where earlier it was a great taboo to go. The courage, conviction and love for dance prompted them to venture on a path which at that point had no direction and was beyond worldly gains. Also in such a tumultuous time, to be born to that tradition was really tough. We need to know, understand and get inspired by these women, due to whom millions are not only learning Bharatanatyam, but it has given dignity and purpose to the art. Here we study a few of them. SMT. BALASARASWATI Balasaraswati was born in 1918 and died at 1984. She rose on the solo Bharatanatyam horizon through her sheer genius. She belonged to the devadasi tradition and was extremely proud of it, though she was never initiated into any temple service. The only dancer to be conferred the prestigious Sangitha Kalanidhi title; she reacted sharply to compartmentalizing the dance into sacred and profane water-tight divisions. For Bala, Shringara / �रĂगार was an all- 1 encompassing mood which included all the other moods. In 1975, speaking at the Annual Conference of Tamil Sangam, Bala made the famous statement, "In Bharatanatyam, the shringara we experience is never carnal, never, never!" Bala came from a home where musicians like Dharmapuri Subbarayar / धरमऩुरी, Tiruvottiyur Tyagier, Hayagrivachari / हयाग्रिवाचारी (from Dharwad / धारवाड़), Govindaswamy Pillai, Ariyakkudi Ramanuja lyengar were frequent visitors, who came to meet and listen to Bala's grandmother, the inimitable Dhanammal, the veena player. -

P O Litics and Change in the Madras Presidency, L88a~L89^* a Regional

Politics and change in the Madras Presidency, l88A~l89^* A regional study of Indian Nationalism. Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy presented to The U niversity of London by Ramanathan Suntharalingam Ju ly 1966 School of Oriental and African Studies ProQuest Number: 11015594 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11015594 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 A bstract The purpose of this thesis is to.describe the process of political change in South India during the decade following the establishment of the Madras Mahajana Sabha in May l88*f. Although the inchoate manifestations of early political consciousness could be traced to the l830*s when the Hindus protested against the proselytizing operations of the Christian missionaries and their official allies, a protest which during the early 1fifties crystallized to give birth to the Madras Native Association, it was not until the formation of the Madras Mahajana Sabha that political activity in South India found its organized and self- su stain in g momentum." The th e s is attem pts to reco n stru c t the events that led to the establishment of the Madras Mahajana Sabha against % the background of political convulsions caused partly by the unpopular rule of Grant Duff and partly by Anglo-Indian opposition to Riponrs policies. -

Carnatic Music Theory Year Ii

CARNATIC MUSIC THEORY YEAR II BASED ON THE SYLLABUS FOLLOWED BY GOVERNMENT MUSIC COLLEGES IN ANDHRA PRADESH AND TELANGANA FOR CERTIFICATE EXAMS HELD BY POTTI SRIRAMULU TELUGU UNIVERSITY ANANTH PATTABIRAMAN EDITION: 2.1 Latest edition can be downloaded from https://beautifulnote.com/theory Preface This text covers topics on Carnatic music required to clear the second year exams in Government music colleges in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. Also, this is the second of four modules of theory as per Certificate in Music (Carnatic) examinations conducted by Potti Sriramulu Telugu University. So, if you are a music student from one of the above mentioned colleges, or preparing to appear for the university exam as a private candidate, you’ll find this useful. Though attempts are made to keep this text up-to-date with changes in the syllabus, students are strongly advised to consult the college or univer- sity and make sure all necessary topics are covered. This might also serve as an easy-to-follow introduction to Carnatic music for those who are generally interested in the system but not appearing for any particular examination. I’m grateful to my late guru, veteran violinist, Vidwan. Peri Srirama- murthy, for his guidance in preparing this document. Ananth Pattabiraman Editions First published in 2010, edition 2.0 in 2018, 2.1 in 2019. Latest edition available at https://beautifulnote.com/theory Copyright This work is copyrighted and is distributed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. You can make copies and share freely. Not for commercial use. Read https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ About the author Ananth Pattabiraman is a musician. -

SRI MUDALIANDAN SWAMI THIRU AVATHARA MAHOTSAVA INVITATION 2.05.2016 (Monday) to 11.05.2016 (Wednesday)

Sri: Srimathe Ramanujaya Namaha Srimath Varavaramunaye Namaha Sri Kooresaya Namaha Sri Vanaadhri Yoginae Namaha Sri Daasarathi Mahagurave Namaha Sri Venkata gurave Namaha Sri Mudaliandan Thiruvadigale Charanam Sri Annavilappan Thiruvadigale Charanam SRI MUDALIANDAN SWAMI THIRU AVATHARA MAHOTSAVA INVITATION 2.05.2016 (Monday) to 11.05.2016 (Wednesday) SRI AMIRTHAVALLI SAMETHA SRI HARITHA VAARANA PERUMAL SRI MUDALIANDAN AADHEENA THIRU AVATHARA STHALAM Pachaivarana nagar, Agaramel, Nazarethpettai. (Near poonamallee) (W): www.mudaliandan.com, (E ): [email protected], [email protected] Sri Mudaliandan Swami Thanian: pAdhukE yathirAjasya kathayanthi yathAkyaya thasya dasarathE: pAdhav Sirasa dhArayamyaham Sri Mudaliandan Swami Thirunatchathira Thanian: meshae Punarvasu dhinae daasarathi hamsa sambhavam yatheendra paadhukaapikyam vandhe daasarathim gurum Sri Mudaliandan Swami Vaazhi Thirunaamam: aththigiri aruLALar arul peruvon vAzhiyE arutpachchai varaNaththil avathariththAn vAzhiyE chiththiraiyil punarpoosam siRakka vandhOn vAzhiyE sIpAdiyam eedu mudhal seer peruvOn vAzhiyE uththamamAm vAdhoolam uyara vandhOn vAzhiyE Oor thirundhach sIrpAdham UnRinAn vAzhiyE muththiraiyum sengkOlum mudi peRuvOn vAzhiyE mudaliANdAn poRpAdhangkaL UzhithoRum vAzhiyE Sri: Sloka on Sri Haritha Varana Perumal Boomav Dharmapure Amirthavalli yAkya Sri aAlingatho BakthAnAm abayaprathAna Nibuno HareEtha rikvArana Vaadhoolothama Vamsa DaasarathinAm Samprapthitho Mangalam SriyEna Sakalam thathAthu Vipilams nArAyana: srinithi Upadesa Rathina Maalai Pasuram by